10.2 Death and Dying as a Social Problem

“Nothing is certain but death and taxes.” This phrase summarizes some of the wisdom of living in a modern economy. If we think back to the sociological imagination from Chapter 1, we know that of course, death is personal. It happens to each of us in a unique and individual way. However, death is also a social event. Our families, friends, and communities walk through the process with us. We depend on the social institutions of hospitals and hospices, and the businesses of mortuaries and funeral homes to care for us. Even the government must issue death certificates for deaths to be considered valid. In this sense, death is also a social problem. Let’s look at why that is.

10.2.1 What is Death?

Determining when a death takes place seems straightforward and obvious. When a person’s body ceases to function, death has occurred. But as one delves deeper into the details and specifics, that task becomes far more complex. Historically, there have long been accounts of people who were determined to be dead, when in fact they were still very much alive. Although not common, such instances were often a result of shallow breathing or faint heartbeats that went undetected. Advancements in medical technology have addressed this possible problem. At the same time, they have introduced new challenges in determining when death occurs. Modern medicine’s ability to artificially keep people alive as their bodies fail raises new and difficult questions in determining when death occurs. Therefore, society found a need to clearly define what determines death, delineate the criteria to be used to establish that death has occurred, and develop a process to socially recognize and certify a death.

10.2.1.1 Clinical Death

The customary method of determining death has centered on the cessation of basic vital signs of life – the absence of breathing and a heartbeat. But advancements in new technology have raised new issues and challenges in using these conventional methods for establishing death. The use of advanced life support systems, such as ventilators, respirators, and various methods of cardio-pulmonary support can now artificially support life for long periods of time. In these cases, a person can be kept “alive” through mechanical means for days, months, and in some cases, years. While in this state, is the person really alive, or has death, albeit artificial intervention, already occurred?

With the ability to keep a person breathing and the heart beating through artificial means for long periods of time, the medical community turned to the concept of brain death to determine death. Based on the work of the 1968 Harvard Medical School Ad Hoc Committee, brain death, or what became known as the “whole-brain” definition of death, involved the following criteria: the absence of spontaneous muscle movement (including breathing), lack of brain-stem reflexes, the absence of brain activity, and the lack of response to external stimuli. This criterion for brain death is used to augment the customary use of vital signs when they may be ambiguous.

10.2.1.2 Legal Death

The definition of death affects many aspects of our daily lives. The death of an individual often triggers government laws that regulate issues directly related to how the body of the deceased is handled and the options for the final disposal of the corpse. Issues arising after death may also require some type of official government documentation verifying a death has occurred. A government-issued death certificate with verified information as to the date, place, and in some cases, the cause of death, is needed to execute wills and inheritances, file necessary taxes, assess any civil and criminal liabilities, and a host of other legal issues regulated by the government.

With the broad-based acceptance of the medical criteria for death, legislative discussion ensued to develop a standardized, legal means for determining that a death has occurred. Efforts focused on revising and updating the legal standards used to determine death that closely aligned with the criteria being used by the medical community.

The Uniform Determination of Death Act was drafted by a United States Presidential commission in 1981 and approved by the American Medical Association and the American Bar Association. This model legislation was subsequently adopted by all of the states, most using the exact language, although several states have added additional regulations. This standardized legislation focuses on the definitional criteria of irreversible circulatory and respiratory cessation, and the whole brain death concept is widely accepted by the medical community and the general public. It also makes a statutory distinction separate from emerging situations associated with the advancement in organ transplantations and the resulting increase in organ donations. This act is currently under review. The Uniform Law Commission (ULC) created a committee to propose possible revisions to address questions that continue to arise. The drafting committee has until 2023 to report back to the ULC executive committee with any possible revisions (Lewis 2022).

10.2.1.3 Social Death

Social death involves the loss of social identity, loss of social connectedness, and loss associated with the disintegration of the body (Kralova 2015). This can be marked by a specific event, such as biological death. But it can also involve a series of changes such as the loss of the ability to take part in daily activities, the loss of social relationships, and/or the loss of social identity during end-of-life and the dying process. When there is a social determination of death, a person’s place in society changes. There is a shift in their social status that denotes a separation from society and community. Establishing when social death occurs, signals others as to the expected adjustments in social interactions.

Social death can change social role expectations, social status, and social interactions. When a person is dying, they may no longer be able to fulfill their social roles. For instance, a mother or father may no longer be able to care for the children. The children may need to become care providers for the parent. Adult children may become the care provider for an aging parent. The meaning of friendship expectations changes and social interaction within community or work settings are altered or severed.

After biological death, the status transition of the deceased from the world of the living to the spiritual realm or the world of their ancestors is often denoted by funerary rituals. Socio-cultural beliefs, values, and norms form the basis for the determination and meaning of social death. In U.S. dominant culture, the meaning of social death may be directly linked to the absence of medical/biological indicators such as breathing, heartbeat, brain-based reflexes, and processes that then lead to various funerary rituals.

In other cultural belief systems, biological death is but one aspect of determining social death. For the Toraja peoples of Indonesia , social death does not come until the body leaves the home. They often keep the body of the biologically deceased in the home as an ongoing social member of the family and community for weeks, months, or even years. During this time, the person is perceived as being sick or in a prolonged sleep. They are fed, bathed, and their clothes are periodically changed. They are talked to, hugged, caressed, and moved to various settings to ensure they are included in family and community activities. The removal of the body from the home and completion of funerary rituals denotes the change in social status and social determination of death. The video in figure 10.4 explores this concept of social death in more detail.

Figure 10.4 Here, Living With Dead Bodies for Weeks—Or Years—Is Tradition [YouTube Video]

As you watch, please consider these questions:

- How does this experience of death challenge your expectations about what it means to be dead?

- How can death be understood socially as well as biologically?

- What kind of losses are involved in death?

10.2.2 Studying Death

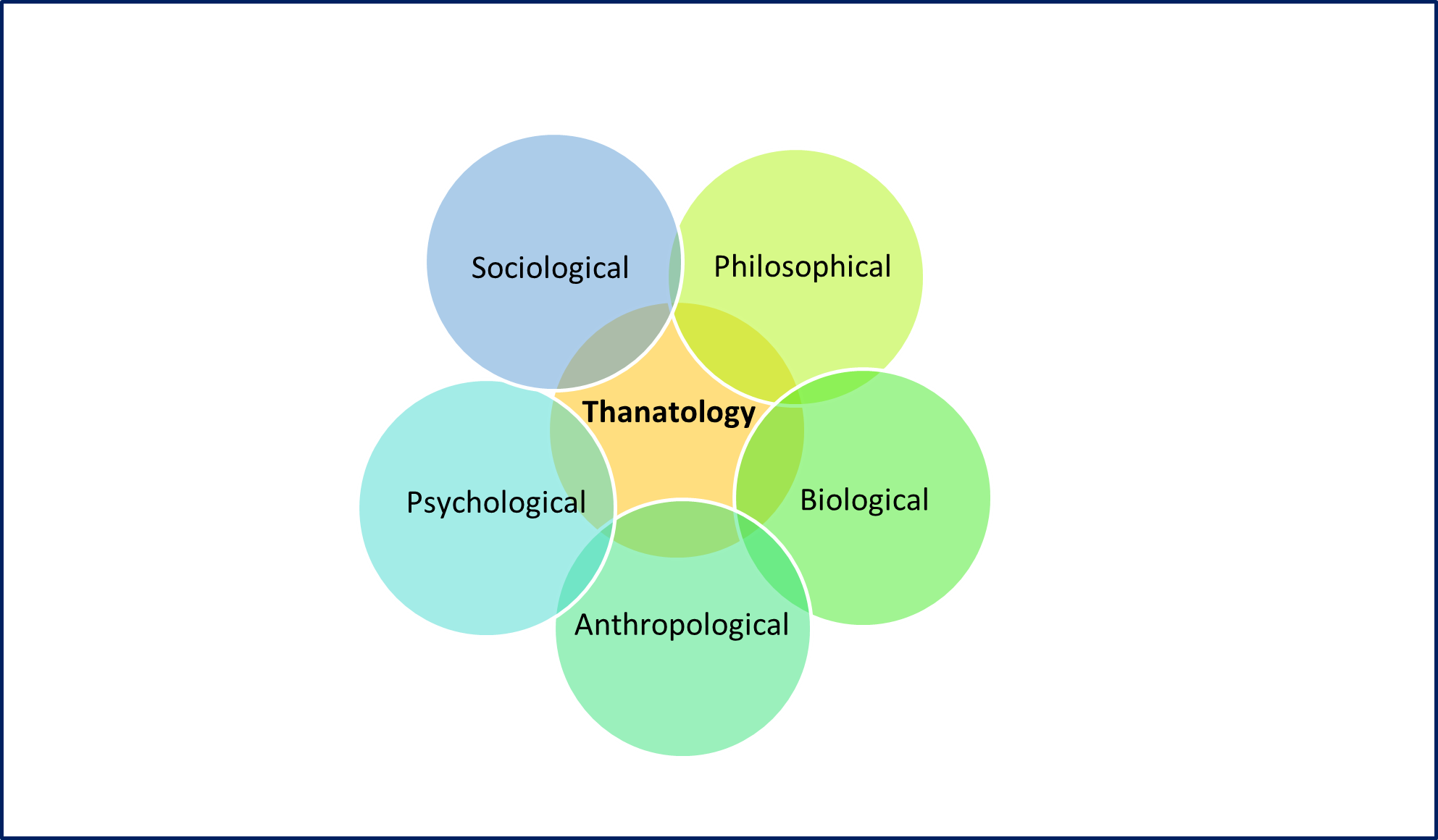

Figure 10.5 Thanatology is Interdisciplinary. Figure 10.5 Image Description

Thanatology is the scientific study of death, the dying process, and bereavement. Death can be studied from many perspectives with each highlighting a different dimension of the complexities surrounding death and dying. Therefore, thanatology taps into multiple disciplines to take in the whole person and their social surroundings. This interdisciplinary study of death relies on contributions from many academic fields of study, as illustrated in Figure 10.5.

10.2.2.1 The Philosophical Approach

Philosophy explores fundamental questions about knowledge, life, mortality, and the human condition. There is a focus on examining the meaning of our existence, the nature of human thought, the essence of the universe, and the connection between them. This approach challenges humans to examine their own beliefs and question the validity of those beliefs. A philosophy-based perspective provides insights into the holistic human experience of death and dying. We and we alone will confront death and our beliefs and perceptions become our reality and our truth. These beliefs then shape the meaning of death and the subsequent actions and responses. Philosophy provides insights into the value-based decisions surrounding death and dying. For instance, in the medical field there are times and situations in which decisions must be made as to who gets priority emergency treatment during times of resource scarcity; is it the patient who has the best chance of survival or the patient who is most urgent at that time regardless of long term outcome.

10.2.2.2 Biological and Medical Approaches

Biology is the science of life and living organisms. The multiple disciplines and subfields that make up this field of study examine the structure, function, growth, and evolution of organisms. Biological sciences and their application to the human body form the foundation of the western healthcare system. Healthcare provider education and training is grounded in a biological paradigm. Western approaches to science and scientific methodology are used to establish a diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment strategy.

A biological perspective provides insights into an array of issues related to the understanding of death and dying. U.S. dominant culture relies on biology and medicine to define when death occurs. This basic, fundamental question may at first seem fairly evident. But upon closer examination, it is a complex issue that relies on biological indicators that lead to questions such as: Does death occur when the heart stops? When internal organs cease to function? When brain activity stops? How long must determining biological conditions exist before we accept that death has occurred? The interpretation and meaning of these physiological indicators are used to establish death. This raises questions for the U.S. healthcare system when providing services for those who hold belief systems that do not place the same emphasis on the biological approach as being the definitive determinant in defining death.

10.2.2.3 Anthropological Approach

Anthropology examines social, cultural, and biological factors to gain a holistic understanding of humanity. Using empirical evidence to study human language, culture, and societies this perspective considers the past when exploring the distinctiveness of social groups. Rituals, practices, and beliefs concerning death and dying reflect the most important cultural values by which people live their lives. What a culture places emphasis on at the end of life indicates what is valued in life. An anthropological perspective can facilitate a comparative analysis of past and present as well as a contemporary cross-cultural examination of death practices. This broadened awareness facilitates the cross-cultural understanding of varied death practices underscores that there is no inherent right or wrong way to address the issues associated with death.

10.2.2.4 Psychological Approach

Psychology examines human behavior and mental processes and explores how consciousness, cognition, and social interaction impact human behavior. This discipline connects social science with the biological sciences by focusing on the physiological and neurological processes in relationship to mental functioning and human behavior. A psychological perspective provides a framework for studying a vast array of death topics including the study of death fears, death anxiety, and the emotions associated with death and dying. There has also been significant work in this field advancing the understanding of the impact of cognitive development on the death experience. Scholars and practitioners more deeply explore issues associated with grief, mourning, and bereavement.

10.2.2.5 Sociological Approach

Sociology is the study of society, social structures, social processes, and social interactions. Sociologists examine how society is organized, how society affects patterns of human behaviors, and in turn, how humans shape society. This broad-based, systematic study of society and social interactions provides insights and understanding as to how external factors affect people’s beliefs, behaviors, and experiences.

At a macro level of analysis, sociology focuses on the role of social institutions in structuring the processes surrounding death and dying. For instance, governments regulate the ways in which a corpse and or human remains can legally be handled. They legislate the process by which the legal definition and medical criteria used to determine when death has occurred. The discipline also explores the impact of social indicators such as class, race, and gender and how social location differentially affects the end-of-life experience such as access to healthcare resources and social supports.

At a micro level of analysis, a sociological approach can shed light on how belief systems and social factors affecting our day-to-day interactions create meaning around death and the dying process.

Thanatology has long recognized the necessity and the value of an interdisciplinary approach to the study of death and dying. Each of the above disciplines contributes a unique body of critical information and insights needed to more fully develop a holistic understanding of death. And sociology, with its focus on the impact of social forces and social processes, plays a critical role in expanding that understanding of death and death-related experiences.

10.2.3 Death as a Social Problem

Death is one of the most intimate and personal issues a person will ever confront. But death is not only an individual event, it is also a social issue that affects society, and in turn, is affected by society. What happens to an individual is affected by the social context within which it takes place, but death also has broader social implications.

At a micro level of analysis, death and the dying process involves the loss of social roles, and a shift in existing roles. For instance, when a parent dies, you lose someone in the parental role. Older siblings, grandparents, or family friends may need to step in and take on parenting responsibilities. Social relationships are also altered. The loss of a member in our social circle affects all who are part of that social network. As a result of a death, the group dynamics and relationships may need to be renegotiated and a new shared meaning developed.

At a social institutional level, death and the resulting loss of a worker, a teacher, or a community leader affects institutional processes and a shift of institutional resources to fill vacated roles. While a single death may have one type of impact, numerous deaths may have a more immediate and significant societal impact. Infection rates, long-term illness, and deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the significant loss of workers. The COVID-19-related workforce issues disrupted the flow of goods and services and are still having an ongoing impact on the overall economy.

Social structures and social processes can also affect an individual’s options and agency. Currently, only 8 states and the District of Columbia have a Death with Dignity law that allows a person who suffers from a terminal disease and meets the required criteria to choose to end their life on their terms. These right to die laws provide an option for eligible individuals to legally request and obtain medications from a physician to end their life in a peaceful, humane, and dignified manner. This option is not available in most states. Only those who are residents or have the resources to travel to the states where it is legal are afforded this choice. Even options concerning when, where, and how to dispose of the body after death as well as where cremains (ashes) can be spread are regulated by laws that can supersede personal preferences and cultural practices.

10.2.4 Social Location and Systemic Inequalities

Although death is an inevitability of the human condition, mortality rates are impacted by social forces and social factors. When and how a person dies is more than just the outcome of individual genetics and human physiology. Life expectancy and cause of death are also affected by social factors such as access to healthcare, quality of life indicators, geographic location, and socioeconomic variables. Differential patterns in life expectancy and death rates based on gender and race/ethnicity are affected by broader social issues and systemic inequalities.

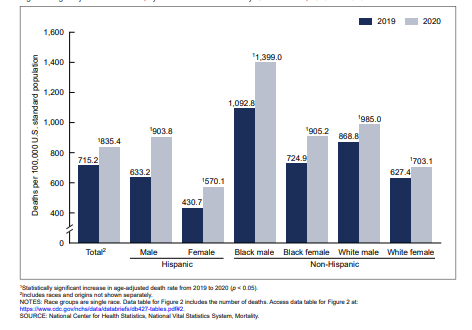

Social institutional features involving work, family, social class, healthcare, and social construction of gender role expectations contribute to the ongoing differential life expectancy, the number of years a person can expect to live, based on an estimate of the average age that members of a particular population group will be when they die. (Ortiz-Ospina 2017) When we look at life expectancy based on gender, we see a difference. Males are predicted to live only 76.3 years on average, while females are expected to live 81.4 years on average. (National Center for Health Statistics Fact Sheet 2021). Comparative death rates based on race and ethnicity also reflect systemic inequalities in social systems and people’s social experiences (Figure 10.6).

Figure 10.6 Age-Adjusted Death Rates by Sex and by Race/Ethnicity United States 2019 and 2020. Black males experience the highest rate of death.

The impact of social inequalities is also evident during significant catastrophic events that challenge society, such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. With the emergence of a new virus, this medical crisis strained social institutions and fundamentally interrupted previous patterns of social activity. We are all at medical risk, but the probability of contracting the virus and the likelihood of death from the infection are affected by social factors. Although physiological factors are at play, social factors such as the type of work, access to healthcare, and socio-economic variables directly impact the risk of infection, rates of serious illness, and likelihood of death. Many of these social risk factors disproportionately impact people based on social location indicators such as race, ethnicity, and social class.

|

Race/Ethnicity |

No. Cases |

Percent Cases |

No. Deaths |

Percent Deaths |

Percent CA population |

|

Latino |

2,816,933 |

43.8 |

39,885 |

43.4 |

36.3 |

|

White |

1,724,621 |

26.8 |

32,116 |

35.0 |

38.8 |

|

Asian |

672,997 |

10.5 |

10,001 |

10.9 |

16.2 |

|

African American |

355,305 |

5.5 |

6,445 |

7.0 |

6.1 |

|

Multi-Race |

64,887 |

1.0 |

1,421 |

1.5 |

1.7 |

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

29,537 |

0.5 |

452 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

50,905 |

0.8 |

571 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

|

Other |

710,586 |

11.1 |

920 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

|

Total with data |

6,425,771 |

100.0 |

91,811 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Cases: 8,002,944 total; 1,577,173 (20%) missing race/ethnicity

Deaths: 92,388 total; 577 (1%) missing race/ethnicity

Figure 10.7 California: All COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by Race and Ethnicity Among Ages 18+

As you look at this chart, you may want to start at the last column. This column reflects the percent of California’s total population for a particular group’s race and ethnicity. If race and ethnicity did not influence the rate of catching COVID-19 or dying from COVID-19, you would expect that columns Cases (column 2) and Deaths (column 4) would match the last column. They do not. Instead, we see that White, Asian, and Multiethnic people have a slightly lower than expected death rate. People of all other races and ethnicities have a slightly higher death rate. When you consider what you learned in Chapter 7 about why this is true for health, you can apply those learnings to understanding the consequences of social location on death also.

10.2.5 Right-to-Die Laws

Throughout this book, we have looked at how laws and changes in the law create and impact social problems. The same is true with the social problem of death. One example of the conflict in this area is around who gets to decide when to die. These laws are called the right to die laws.

In recent decades there has been a growing movement to ensure that individuals have the autonomy and agency to control their own end-of-life decisions, including the right to die. Social institutions such as health and medicine and the government have set the standards, accepted practices, and legal statutes concerning end-of-life options. These regulations and standards may conflict with the personal preferences of those who are in the dying process.

This highlights a fundamental question, “Who has the ultimate right to decide how and when an individual’s life ends?” Those working for the passage of so-called “right-to-die” legislation (also referred to as physician-assisted suicide or physician-assisted death) assert that individuals should be able to make the decision as to how much pain, suffering, and debilitating symptoms at end-of-life they should endure, not the government.

The first right-to-die law in the United States was enacted in Oregon (1997). Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act (DWDA) allows a terminally ill individual to end their own life with a self-administered lethal dose of medication prescribed by a physician for that purpose. The Oregon law sets out a very structured procedure with specific requirements and criteria that must be met for an individual to utilize this option.

Participants must be:

- At least 18 years or older

- Capable of making and communicating health care decisions for him/herself

- Diagnosed with a terminal illness that will lead to death within 6 months

- Must be able to self-administer and swallow the medication or self-administer via a feeding tube

- As of March 2022, Oregon is no longer enforcing the previous residency requirement

Procedural and core criteria include:

- Two oral requests must be made to the physician at least 15 days apart

- A written request to the physician must be signed by two witnesses

- Two physicians must confirm the diagnosis and the prognosis

- The physician must verify that the patient is capable of making and communicating their own health care decisions

- The physician must inform the patient of feasible alternatives

(Oregon Health Authority: Death with Dignity Act)

Oregon’s DWDA has survived multiple legal and political challenges and has become a model for many other states who have sought out this protection as an end-of-life option.

As more states continue to pass right-to-die legislation and many others consider the issue, there is still an ongoing debate over this type of legal protection for self-determination at end-of-life. Those who support physician-assisted death at end-of-life as a legal option assert that the right to die in these situations is a fundamental human right. Advocates support patient autonomy and choice over government control of these decisions.

Those who oppose this type of legislation express fear over a lack of oversight at the moment of death. They cite concerns that the final decision to end one’s own life will be made by others on behalf of those who may be too ill to speak on their own behalf. Some fear the normalization of physician-assisted death to the point that patients will feel responsible to relieve the burden their care places on their loved ones. And many believe it is the job of physicians to alleviate suffering, not the patients themselves. As this discussion continues, 8 states currently have a right-to-die law and many others are considering some type of legislation to protect this end-of-life option. Many of these concerns are raised in the video in figure 10.8.

Figure 10.8 Right-to-die movement finds new life beyond Oregon [YouTube Video]

As you watch this 9:27 minute video, please consider these questions:

Who is deciding when to die?

Why is right to life an example of the social construction of death?

10.2.6 Licenses and Attributions for What is Death?

“What is Death?” by Patricia Antoine, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.4 Death is a Social Experience https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hCKDsjLt_qU

Figure 10.5 Thanatology is Interdisciplinary Figure by Kimberly Puttman, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.6 Age-Adjusted Death Rates by Sex and by Race/Ethnicity United States 2019 and 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db427.pdf, (Murphy, S.L., et al., 2021)).

Figure 10.7 California: All COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by Race and Ethnicity Among Ages 18+ California Department of Public Health. (2022). COVID-19 Age, Race and Ethnicity Data https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/COVID-19/Age-Race-Ethnicity.aspx

Figure 10.8 Right to Die Movement Finds New Life https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fDAkaOgdF3c