10.4 Social Location: Life Course, Aging and Ageism

|

Figure 10.12 Please take a moment to look at this picture of the baby, mom, grandmother, and great-grandmother. They look so happy to be together. As you consider your own life and your own family, please consider how your identity changes over time. Does your access to power and privilege also change over the course of your life? Sociologists and other social scientists study the human life course or life cycle to make sense of these questions and many more. As human beings grow older, they go through different phases or stages of life (figure 10.12). It is helpful to understand aging in the context of these phases. A life course is the period from birth to death, including a sequence of predictable life events such as physical maturation. Each phase comes with different responsibilities and expectations, which of course vary by individual and culture.

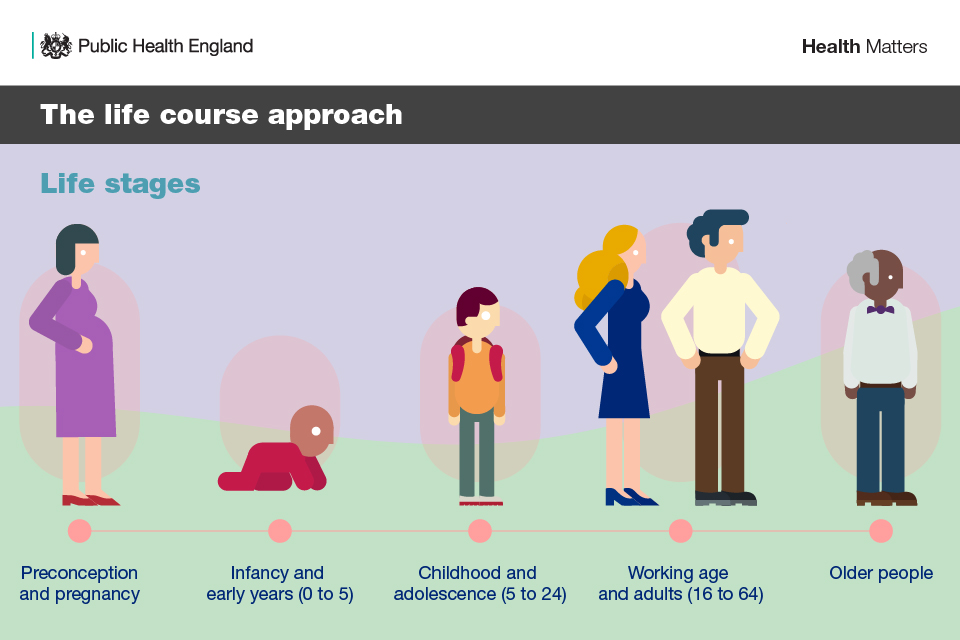

Figure 10.13 The Western model of the life course or life stages. Which stage are you in? The life course in Western societies often includes preconception and pregnancy, infancy, childhood, adolescents, adulthood, and old age (figure 10.13) Children love to play and learn, looking forward to becoming preteens. As preteens begin to test their independence, they are eager to become teenagers. Teenagers anticipate the promises and challenges of adulthood. Adults become focused on creating families, building careers, and experiencing the world as independent people. Finally, many adults look forward to old age as a wonderful time to enjoy life without as much pressure from work and family life. In old age, grandparenthood can provide many of the joys of parenthood without all the hard work that parenthood entails. And as work responsibilities abate, old age may be a time to explore hobbies and activities that there was no time for earlier in life. But for other people, old age is not a phase that they look forward to. Some people fear old age and do anything to “avoid” it by seeking medical and cosmetic fixes for the natural effects of age. These differing views on the life course are the result of the cultural values and norms into which people are socialized, but in most cultures, age is a master status influencing self-concept, as well as social roles and interactions. The stages of a life course are culturally defined. Sociologists, health practitioners, and other researchers may break old age into more stages so that they can study aging populations in more detail. Other cultures may use other life stage approaches. Hindu people recognize four life stages. The first stage is Brahmacharya, the student stage. This stage includes birth, childhood, and studying. In this stage, you are generally dependent on others to care for you. The second state is Grihastha, the householder stage. In this stage you establish yourself as an adult, caring for your family and the community. The third stage is Vanaprastha, the hermit stage. In this stage, you are likely a grandparent. You have time for spiritual growth and learning. Finally, the last stage is Sannyasa, the wandering stage. In this stage, people become less concerned with the world, and become more connected to God. Historically, people would renounce their possessions and wander freely, talking to people about spiritual matters. You may also experience changes in power and privilege as you move through life stages. Young children, as you might expect, have little power. They depend on others to care for them. When a person turns 18 in the United States, they can vote, which is a level of power and privilege. As people move from adulthood to senior citizen, they may experience more frequent ageism – discrimination based on age. Often, your power and privilege decline as you age. Although ageism is common in Western cultures, these beliefs and behaviors are not universal. In Indigenous cultures, elders are respected for their wisdom and life experiences. In Korea, young people show respect for their elders, and are required to care for elderly family members. As we look at the life course related more specifically to death and dying, professionals use this model in two ways. The first way helps us understand what constitutes a good death. The institute of medicine defines a good death as one that is free from avoidable death and suffering for patients, families, and caregivers in general according to the patients’ and families’ wishes. When children die, for example, grief is particularly challenging in part because their death is unanticipated – not part of the normal life course. When people who are poor die of diabetes or heart disease as young adults, this is also not a good death because these deaths could have been prevented. Medical professionals also integrate this idea of a good death into their models of health and illness. This infographic is intended for doctors, so it is very complicated. However, if you examine it piece by piece, you will find that we have actually covered most of these ideas in this book. The infographic helps to synthesize our knowledge.

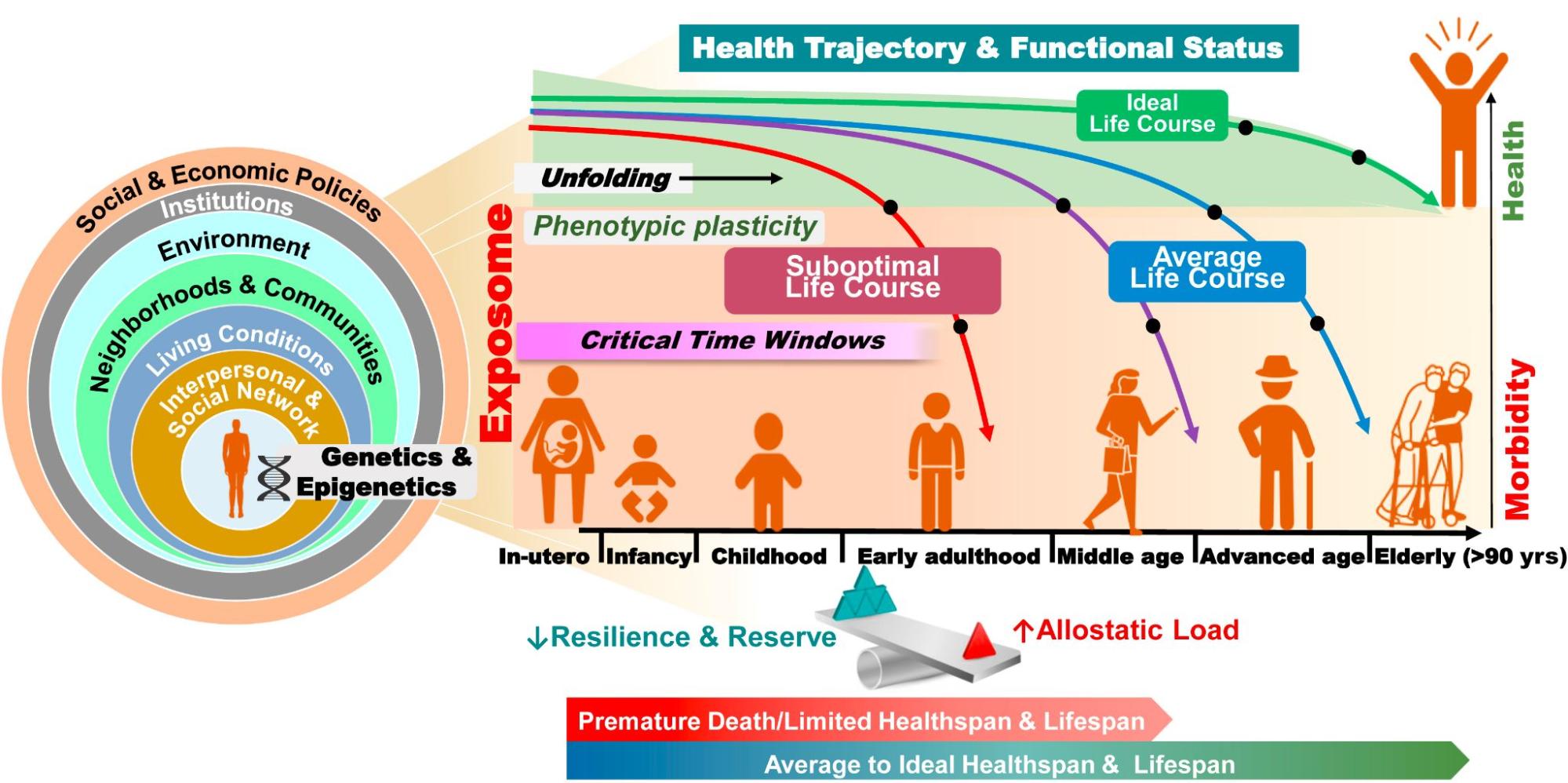

Figure 10.14 The Evolution of Health Trajectories Under the Influence of Macro- and Micro-Level Factors The circles at the left side represent the social ecology model that was introduced in Chapter 1. A person’s health is impacted at the micro level of individual interactions to the macro level of the laws and policies that create or change structural inequality. People who talk about racial environmental justice, as in Chapter 5, might notice how neighborhood exposure to oil or coal burning would impact health outcomes. The Exposome is the equivalent to Adverse Childhood Effects (ACEs) or the protective factors that we discussed in Chapter 7. The chart maps resilient heath to less health during the aging process. It also shows how the likelihood of illness or death changes depending on social factors. Finally, the chart displays how health and illness may unfold over the life course, depending on social and individual factors. The concept of life course then, helps sociologists understand how a “good” life and a good death unfold for people from a particular culture. When a life or a death does not unfold that way, sociologists can explain why. Social problems scientists can then propose action. Activists, community members, and governments can act or choose not to act to support good living and good dying for everyone. |

10.4.1 Licenses and Attributions for Social Location: Life Course, Aging and Ageism

“Social Location: Life Course, Aging and Ageism” by Kimberly Puttman, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.12 Photo by Stacy Shintani on Flikr Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

10.4 “13.2 The process of aging” Definition of life course and related examples Sociology 3e, lightly edited and “13.3 Challenges facing the elderly” Definition of Ageism Sociology 3e lightly edited

Figure 10.13 The Western model of the life course or life stages. Which stage are you in? Heath Matters UK https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-life-course-approach-to-prevention/health-matters-prevention-a-life-course-approach © Crown copyright All content is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0, except where otherwise stated

Figure 10.14 The Evolution of Health Trajectories Under the Influence of Macro- and Micro-Level Factors https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.10.011 Fair Use