11.1 Chapter Overview: Our Fire: The Echo Mountain Fire

My thanks to the survivors of the Echo Mountain Fire and the people of Otis, Oregon. Your willingness to fight to bring your neighbors home inspires both this chapter and its author. —Bethany Grace Howe

Figure 11.1 The Story of the Echo Mountain Fire: Please watch this 6.42 minute student created video by clicking above. What social problems do you see in this video? How might they intersect? Do you see interdependent solutions at work? Opening Question: If you had ten minutes to leave your home because of a natural disaster, what would you take with you?

Late on the afternoon of Sept. 7, 2020, there was a significant east-west wind event along the west slopes of the Coast Range. Unexpected but powerful, it turned a still-unknown ignition source into rapid fire growth in the unincorporated Lincoln County town of Otis. Located just a couple of miles inland from the coast, wildfires were not a concern for most Otis residents in an area that gets nearly 100 inches of rain a year.

The blaze started in two places.The first fire began at the summit of Echo Mountain, approximately three miles in from the Pacific Ocean. The second started in the Kimberling Mountain area, approximately three miles east of Echo Mountain. The first fire then tore down the side of Echo Mountain, largely moving east and destroying the homes on the slopes of Echo Mountain. Simultaneously, the second fire moved west from Kimberling Mountain, where it would eventually destroy many of the homes on the banks of Panther Creek. By Sep. 8 the blazes had joined and were officially named the Echo Mountain Complex Fire.

Figure 11. 2 fire blackened properties, still smoking – Likely Matt Brandt Photograph

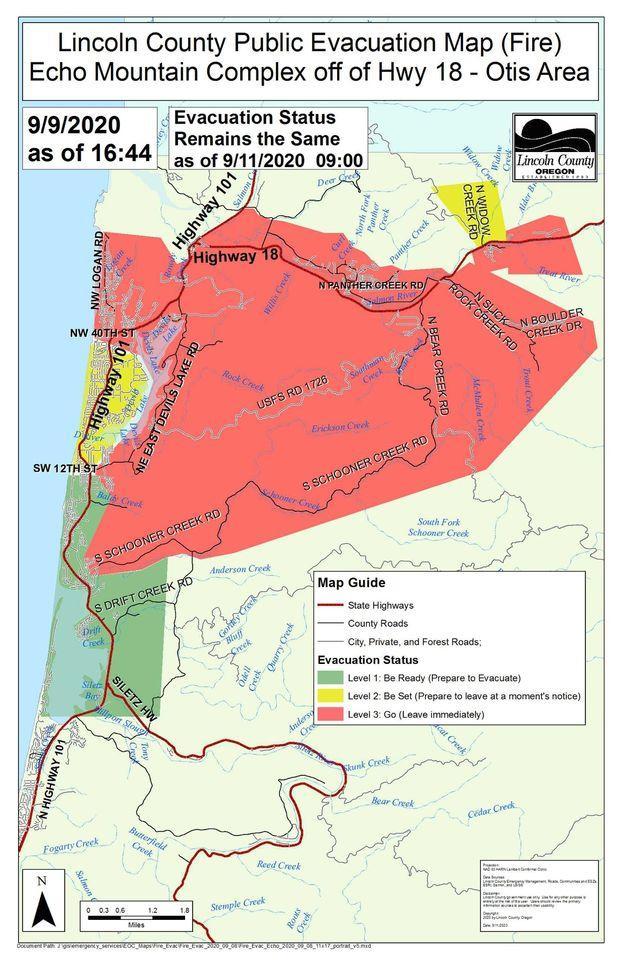

Figure 11.3 Echo Mountain Fire Evacuation Map – Otis, Oregon, located just to the east of the Pacific Ocean. For area residents, this map conveyed what matters: Red was “Go now!”yellow was “Be set to leave,” while green told them to “Be ready to leave.” Although Sept. 7, 2022 started with area residents uncertain, by Sept. 8 all of Otis and Lincoln City were in the red.

The fire’s destruction was far from over, however. First, it moved along the north bank of Salmon River, and then along the south bank after crossing the river. Finally, it moved south and east, skipping from ridge to ridge. There, it destroyed more than a dozen more homes in the Highland Estates neighborhood and even a few on the northeast edge of Lincoln City.

11.1.1 Otis destroyed, Otis spared

In the end, the fire burned 2,500 acres, the smallest of the five fires that week which would eventually burn more than a million acres across Oregon (Urness 2020) That small size, however, hid the magnitude of the destruction. These nearly 300 homes – one-third of the town – represented the lives of more than 800 people.

And Otis was not alone that summer. The Echo Mountain Fire was one of five major fires that destroyed thousands of homes across the state of Oregon, with the destruction made national news. Despite being only one-quarter of one percent of the acreage burned in Oregon, however, more than six percent of the homes lost were in Otis.

What did not make the news, however, were the long-term crises that had beset the town before the first flame erupted. Houseless people, harmful drug use, poverty, a lack of education, cultural barriers, and structural racism were just a few problems in Otis long before the fire.

To properly understand the recovery of Otis after the Echo Mountain Fire—or any community affected by crisis—you must start with intersectionality. Before and after this life-changing event, both individuals and the community were experiencing multiple social problems simultaneously. This complexity is yet another layer in why social problems are so hard to impact.

One long-time Otis resident could not prove to the government she deserved financial assistance without asking her abusive ex-husband to testify on her behalf. Anundocumented Latino was afraid to reach out for government support for fear they and their family could be deported. A disabled senior could only choose to sell her property because she could never afford to rebuild on it. All three of these stories—and dozens more just like them—are evidence of how structural inequalities can make community disaster recovery more difficult. More than that, they illustrate how government response to natural and health disasters can actually magnify someone’s personal crisis by ignoring the structural inequalities present in their life before the disaster.

Fortunately, the organized response to the Echo Mountain Fire was never entirely in the hands of the government. Through the efforts of volunteers and regional nonprofits, the people of Otis took charge of their own recovery.

Figure 11.4 #OtisStrong remains the rallying cry for fire survivor efforts. (The hats came a little later than the bumper stickers).

#OtisStrong was the hashtag and the name that survivors picked for themselves. Within mere days of the fire, you could buy bumper stickers and T-shirts with this logo. Now you can buy that hats, shown in figure 11.4. The hashtag came to symbolize more than just a belief or a feeling. It was a commitment to action. It was the kind of action you hear about in a lot of places after a natural disaster, unexpected natural events that cause significant loss of human life or disruption of essential services like food, water, or shelter. (Drabek 2017) Families helped each other to sift through debris and move blackened trees. Community members stepped forward to lead those around them who seemed unable to take the next step.

Their response drew state and national attention for its community-centered approach to disaster recovery. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) disaster recovery is the phase of the emergency management cycle that begins with the stabilization of the incident and ends when the community has recovered from the disaster’s impacts (n.d.: 313). More importantly, the response unified a community, and built a stronger Otis—for both those who’d always been there, and even some of those who had not.

11.1.2 Focusing Questions

In this chapter we will explore how many of the social problems you’ve come to understand in this textbook impacted the residents of Otis, Oregon. We ask you to apply examples from the Echo Mountain Fire recovery to your exploration of these questions:

- How is disaster recovery a social problem, using qualitative and quantitative data from the Echo Mountain Fire?

- According to sociologists and survivors, what are the causes and consequences of overlapping social problems?

- How can natural disasters illuminate, amplify, or reduce structural inequality?

- Can celebrating diversity create resilience rather than a polarized community when recovering from a disaster?

- How effective were the interdependent recovery efforts in supporting survivors to recover physically, financially, mentally, and spiritually.

This is the story of #OtisStrong.

11.1.3 Licenses and Attributions for Chapter Overview: Our Fire: The Echo Mountain Fire

“Chapter Overview” by Bethany Grace Howe is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 11.1 Video created by SOC206 Marc Brooks and Videographer Samantha Kuks (check spelling) as part of the Open Oregon Open Pedagogy Project

Figure 11.2 fire blackened properties, still smoking – Likely Matt Brandt Photograph

Figure 11.3 Echo Mountain Fire Evacuation Map – Otis, Oregon, located just to the east of the Pacific Ocean. https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/map/7179/5/105810 Government source fair use

Figure 11.4 #OtisStrong remains the rallying cry for fire survivor efforts. Photo by Amy Brown. All Rights Reserved.