11.2 Who Lives in Otis? Setting the Stage of Social Problems

Prior to September of 2020, the residents within the community of Otis might have at best been considered disconnected. Political sociology defines disconnection as the breakdown of connections among and between people (Putnam 2000). In healthy communities, most people are connected. They have social capital, social networks or connections that an individual has available to them due group membership. We first looked at the relationship between social capital and harmful drug use in Chapter 8. For the people of Otis, social connections were weak at best. .. Social capital allows people to build community because they cooperate in everyday life and trust each other. This was limited in Otis, particularly in the years leading up to the fire.

The neighborhoods that long-time residents fondly remembered, had been replaced by increasing gaps between middle-class residents and those who struggled to get by. Numerous homes that had once been the pride of the neighborhood had fallen into disrepair, junk and uncut weeds filling the lawn. In school, students could be heard insulting one another: “Well, at least I don’t live up Panther Crick.”

Was this the entirety of Otis? It was not. Many residents were and remained proud of their homes and location. Still, even these residents were aware that time had not been kind to Otis. The collective will to solve these problems as a community was decreasing year after year. The gaps between those who loved Otis for what it was and those who took advantage of what they saw it becoming were enormous.

In any description of a social problem, we see a conflict in values. In Otis, previous to the fire, we see the conflict as we look at each of the properties. People who valued the safety of being part of a larger community with joint standards and expectations, versus those who moved to Otis to live their lives largely disconnected from them. Residents who enjoyed being part of their neighbors’ collective friends group, versus those who wanted simply to be left apart from even those geographically next to them. Homeowners who took pride in their property and possessions, versus those who might not even live on site, often renting their property to anyone who could pay the cheap rent, regardless of their destructive behaviors.

Their experiences, their frustrations and successes, their lives and their loss, are the foundation for the remainder of this chapter. More critically, however, these are their stories – five of them specifically. I’ve changed their names and other pieces of identification that would allow any Otis-informed reader to identify the lives to which I refer.

Each incident, however, each of these individuals’ intersection with the social problem impacting their lives and recovery is true.. Perhaps just as importantly, while narratives that consolidate community stories into individual lives often meld the experiences of multiple people into one person, that is not the case here. These things – all of them – happened to just five people, the magnitude of the overlapping social problems depicted honestly.

Their lives are deserving of nothing less.

11.2.1 Qualitative Data: Our Stories

Figure 11.5 The US flag, shredded by winds, obscured by smoke, hanging from the ladder of a fire truck near Otis. Picture from Echo Mountain Fire Facebook

11.2.1.1 Betty:

In her 80s, Betty had been living on a subsistence level income for years. Unable to even pay her property taxes, she had fallen into default years earlier. She figured someone would pay them from her small estate when she died. Betty’s life was limited by health concerns, however. With severe COPD, Betty no longer traveled anywhere independently other than the garden outside her front door. Her personal interactions were largely limited to the neighbors who would stop by to talk to her as she sat on her favorite bench, tended her flowers, and watched the birds.

11.2.1.2 Carol:

When the fire broke out, Carol had been divorced from her husband for about one year. A survivor of spousal abuse, she’d for years had a substance use disorder, most recently with methamphetamines. Since the divorce, she’d largely moved from place to place in Otis, paying cash to a variety of people so she could sleep on their couch for a few weeks at a time. Her ex-husband had agreed to let her put what few things she owned in a storage area on the edge of the property near her former home. She traded doing some yard work for even that kindness. She kept a sleeping bag there, just in case there was absolutely nowhere else to stay. Still, she rarely felt safe staying there, and so she rarely did.

In many parts of Otis she was seen as a “meth head.” Unlike many drug users in the community, however, Carol was still viewed by most residents as a person with problems, rather than a problem for the community itself.

11.2.1.3 Fernando:

Although he would eventually become the leader of fire recovery for an entire community, at the time of the fire, Fernando was one more Otis resident living where the pavement and dirt roads connected amidst the trees. He and his wife had been residents of Lincoln County for nearly 20 years as immigrants. Their son, a local high school student, had been born in the United States. Both Fernando and his wife were respected and viewed as leaders by the larger Hispanic community. Fernando often acted as a translator and liaison to local governments and churches.

Still, over the previous four years they saw neighbors they had never known politically or even personally begin to fly Trump flags from their homes and vehicles, with stickers demonizing immigrants. In conversations they would hear some of their neighbors say “Send them back,” in reference to their birthplace of Mexico. Sometimes they could assume their neighbor didn’t know they could hear them.Otherneighbors didn’t seem to care if they could be heard or not.

11.2.1.4 Tommy & Wendy:

Just into his 70s, Tommy was in failing health. A handyman by trade, a lifetime of physical labor and accidents he could never afford to have treated properly had left him permanently disabled. He was unable to walk anything but short distances. A traumatic brain injury following being struck by a forklift had left him sometimes unable to understand basic conversations or make complex decisions. Unmarried, he rented a small, dilapidated trailer on an old friend’s property. Having never graduated high school and for the most part unfamiliar with the internet, he found it difficult to access social services that might have been able to help him. It was not a life most people would understand or want, but for Tommy it was manageable and he made it work – for the most part.

His older daughter Wendy, had been a concern as long as he could remember. A drug user since her teens. mainly of inhalants, such as kerosene, paint thinner, and glue, she did manage to stay in touch with him. That’s how he’d learned a few years ago that Wendy’s drug abuse had started following long-term sexual abuse by a family friend. Now in her early 40s, she had been hospitalized multiple times as a result of her use of inhalants. Each time the long-term damage to her liver and heart was measurably worse. Although not technically without a home, Wendy moved frequently, often living with people who enabled her harmful drug use.

Betty, Carol, Fernando, Tommy and Wendy: Five lives forever changed by the Echo Mountain Fire. The flag in figure 11.5 was a symbol of the distruction of the fire and a call to hope. For all but Fernando, the overlapping social problems of a lack of formal education, poverty, substance use disorders, and housing insecurity would impede most every aspect of their lives in ways that even those who worked to help them would be powerless to stop.

Some of these problems- poverty, houselessness, harmful drug use – had been building in their lives for decades Others were newer, such as the political polarization of the country and COVID-19. Whatever the cause or how long it had been festering in Otis, however, these five – like many local residents – felt their lives and community had been under siege since long before the fire ever roared down Echo Mountain.

11.2.2 Quantitative Data: Demographics of Otis

Along with stories, sociologists define populations with numbers. When we describe Otis by the numbers, we are discovering whether the folks impacted by the fire share the same characteristics as people in Lincoln County, people in Oregon, or even people like you.

11.2.2.1 Age

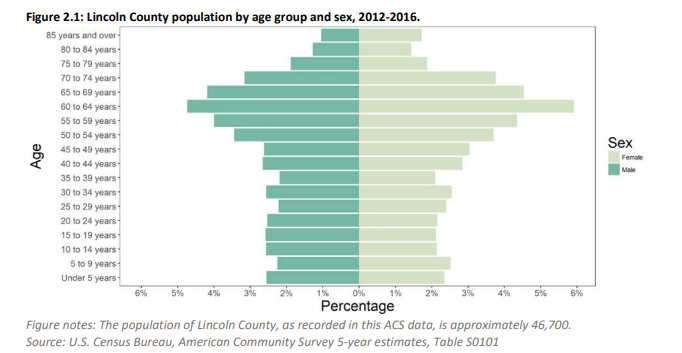

Figure 11.6 Lincoln County Population by age group and sex. Compared to the rest of Oregon, the population is older.

There are no complete demographic figures for those specifically impacted by the Echo Mountain Fire, except for two numbers from FEMA. First, 30% of those who lost their homes had children of some age in the household, such as Fernando. Second, approximately 30% of those who lost their homes were seniors like Betty and Tommy. These numbers remain fairly consistent across the larger population of Otis, in terms of overall census data (Gates and Cooke 2011). Unlike Oregon overall, the population of Lincoln County tends to be older and there are fewer children. Figure 11.6 shows this demographic distribution. The age demographics for Otis are likely to similar.

11.2.2.1.1 Social Location: Seniors and Wildfire Recovery

Many of the demographic factors and social problems we’ll examine in this chapter will likely make sense to you in terms of their impact on recovery. Poverty, racism, substance use disorders, an inability to access or make use of the internet: what you’ll learn about how these intersect with recovery from a disaster probably already includes knowledge of the problem itself.

“Seniors,” as a demographic, is somewhat different, however. Quite frankly, becoming a senior is a good thing. Most of us would hate to think of our lives ending before that age. In Chapter 10 we explored concepts and models related to life course. We saw that getting older is normal, even in a culture that values youth. Being old isn’t a problem.

As Betty and Tommy’s senior experiences make sadly clear, there is a sad contrast between the lives lived by most seniors in America and they and the seniors like them in Otis. No matter how spry your grandparent may be, many seniors in Otis who are barely even 60 already have disabilities that impact their daily life. Even your “negative” memories of a grandparent in a care facility may have made you think that anything must be better than living in such places (Verhage et al. 2021). Perhaps Betty and Tommy would agree with you.

Consider also, however, the lives they lived before September of 2020. Their prior lives and experiences had left them unable to afford long-term care. Instead, each day of their lives was like walking a tightrope. Each step was carefully taken, lest any mistake make their lives worse. The fire destroyed their tightrope.

Certainly this is not true of every senior in Otis. As we’ll review shortly, it was statistically not even the majority of them. But it was many of them, all of them living far from whatever our most positive and sometimes even negative images of what being a senior is supposed to be. It certainly was not a life that most of us would choose.

If you asked them, it wasn’t what they would have chosen 40 years ago. If someone would have asked them what they believed their future held, the life they found themselves in likely was not it. But it was their life in 2020. Even on their limited income they could keep the power on, the water running, and gas in the car. They had their books, their DVDs, maybe even some streaming services on their TV. Year-round there were the sounds of the wind in the trees, or the rushing water in the river. There were birds and wildlife all around them – and for some, even for people like Betty and Tommy, all of this was a valued part of their lives. These small pleasures were everything to them.

And those occasional emergencies? They were usually fixed with the help of that one neighbor who always took their calls.. The fire destroyed all of that. It destroyed the tightrope upon which all of it was balanced – and they fell. They fell into an abyss of uncertainty and fear.

The government, the nonprofits, even the most well-meaning of people call it recovery. They mean that word in the kindest, purest sense – and in my experience they embody it as they can as they work with people in trauma.

But for those seniors like Betty and Tommy, it is not their life, and it never will be.

11.2.2.2 Race and Ethnicity

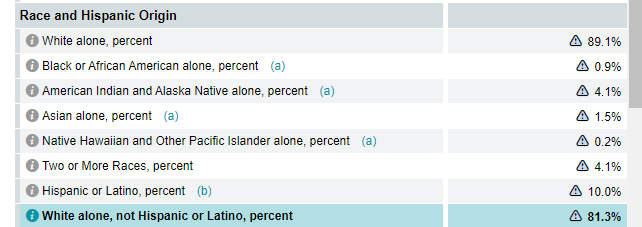

Figure 11.7 Race and Ethnicity Lincoln County Oregon US Census 2021. Although Lincoln County is predominantly White, Hispanics and Lantinos make up 10% of the population.

Similar truths hold for racial data.There is no formal accounting of the racial and/or ethnic make-up of survivors of the Echo Mountain Fire. Beyond empirical data, however, was research we conducted at Echo Mountain Fire Relief (EMFR), the first local nonprofit to work in the area. (This is the organization I directed.) Based on our phone calls to local community service agencies that service the Latino population, it is believed there were approximately 25 to 30 families of Latino heritage like Fernando’s who lost their homes in the fire. This corresponds with the most recent U.S. Census data, which identifies the Latino population of Lincoln County at 10 percent, as shown in figure 11.7.

There is even less data on Native American people. Like Latino impacts, the impacted population is expected to be similar to their share of the general population: 4%.

11.2.2.2.1 Social Location: Race – Stereotypes Disproved

Something to remember as we begin to paint the statistical portrait of Otis: No statistic, no matter how comprehensive or well-researched, tells the story of any one individual within that statistical group. For instance, you will read that more Latinos in north Lincoln County live in poverty than their White counterparts. Yet, within the five stories told here, the only person not living in poverty is Fernando, a Latino. Indeed, despite their higher rates of poverty in Lincoln County, the majority of Latinos in Lincoln County, even in Otis, do not live in poverty.

By now, you are likely to be comfortable with the idea that our social world is socially constructed. In Chapter 3, we discussed how erroneous stereotypes and beliefs underpin audism, racism, sexism, and other structural inequalities.

As we look at the inequality present in the demographics of Lincoln County and in Otis, it is vital to guard against using the data to reinforce erroneous stereotypes.

Most of the residents of Otis are not in poverty, uneducated, engaged in substance use disorders. It is that simple. If you see or meet a resident of Otis, to apply any negative stereotype to them would be both unfair and inaccurate. No, we cannot forget that more of their neighbors deal with social problems than most communities, but we must be equally sure to remember that not all of them do. This bears repeating especially when it comes to groups with which we may already stereotypically associate negative behaviors or outcomes.

For instance, Latinos are often stereotyped as low-skilled workers. One media study found 73.1 percent of media images they examined depicted Latinos as engaged in low-skilled jobs. In reality, however, only about one-third of that many Latinos – approximately 25 percent – work in such jobs.

These errant perceptions play a role in Otis, too. When Fernando overhears his neighbors saying “Send them back,” the chant implies that every Latino is undocumented. The same media survey cited earlier finds this perception may not be limited to just racists. More than half of the media images the surveyors examined suggested the same – even though in reality nearly seven out of eight Latino Americans were born in the United States.

11.2.2.3 Social Class

As you will remember from Chapter 4, class is primarily defined as the amount of income and wealth of a group of people. Let’s look at the socio-economic-status of the people of Otis. Data depicting the overall economic health of Otis residents is among the most readily available. Whether the gap between state and county, or north Lincoln County and Otis, the numbers each time portray an increasingly negative picture of the overall SES of the Otis area:

|

Living below poverty line |

11.0% |

14.4% |

15.3% |

23.7% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Median household income |

$65,667 |

$50,775 |

$46,080 |

$43,594 |

Figure 11.8 Percent of Poverty line and Median household income Oregon, Lincoln County and Otis

As compared to the rest of the state, the number of people living in poverty in Otis is more than double that of Oregon as a whole, as shown in figure 11.8. The median household income in Otis is roughly two-thirds of that as compared to the rest of Oregon. Certainly, these numbers do not represent the majority of Otis residents. They do, however, represent Betty, Carol, Tommy & Wendy. These numbers provide yet another piece of evidence that SES plays an enormous role in recovering quickly and those whose story is far more fraught with problems.

The number of people living in poverty also intersects with race. Hispanic residents of Lincoln County are 64 percent more likely to live below the federal poverty line, at three out of 10 Hispanic residents of Lincoln County. From readily available demographic data it is unknown if Hispanic residents of north Lincoln County are more likely to live in poverty than their peers elsewhere in the county.

11.2.2.3.1 Social Location: SES

Interpreting SES Data: What Conclusions can you draw?

Caution should be taken when using county-wide statistical data. Whether it is from the U.S. Census or Lincoln County Community Health Assessment, this data may statistically underestimate the negative forces at play in Otis. Readily available data from these two sources often does not break down the unincorporated community of Otis into its statistics. Some readily available statistical data does separate the different regions of Lincoln County, such as the U.S. Census. Accordingly, the majority of statistical comparisons used in this text will use census data for Lincoln City, Oregon. This data is more reflective of the residents of Otis than the county as a whole.

For example:

- While census data shows 4.7 percent of Lincoln County residents were born outside the United States, that number goes up more than half to 8.1 percent when you look at Lincoln City alone.

- Percentages of residents having a high school degree and/or a bachelor’s degree show fewer people in Lincoln City have higher education than the county as a whole.

- The number of people under 65 in Lincoln City with disabilities is higher than the rest of the county as a whole.

- The number of people without health insurance is higher in Lincoln City than the county as a whole.

Even this data as an overall indicator of the economic status of Otis must be used with caution, however. For even these statistical comparisons of Lincoln County to Lincoln City likely fall short of illustrating the true economic gap between Otis and the rest of Lincoln County and even Lincoln City. For instance, the average home in Lincoln City sells for over 20 percent more per square foot than the average home in Otis. Home values are an indicator of a community’s overall socioeconomic status, even positively intersecting with narrow individual factors such as how healthy community residents’ hearts may be.

Still, the reader is encouraged to remember that even when the data indicates a negative situation in Lincoln County or even Lincoln City via statistics, the reality is that it’s likely the disparity and the negative conditions measured are even worse in Otis.

11.2.3 Licenses and Attributions for Who Lives in Otis? Setting the Stage of Social Problems

“Who Lives in Otis?” by Bethany Grace Howe is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 11.5 The flag during the fire source: [1] Picture from Echo Mountain Fire Facebook:

Figure 11.6 Lincoln County Population by age group and sex page 20 Public Domain

Figure 11.7 Race and Ethnicity Lincoln County Oregon US Census 2021 Public Domain

Figure 11.8 Percent of Poverty line and median household income Oregon, Lincoln County and Otis – created by Bethany Grace Howe from <data Source> CC-BY-4.0