11.3 The Interconnected Social Problems of Wildfire Recovery

In the two years I worked in fire recovery, I began to see the lived experiences of people like Betty, Carol, Tommy, and Wendy as being trapped in a slow-moving landslide that was inevitably pulling them down. On any given day the movement was almost invisible. But over time, the distance they had fallen was clear. The social problems that defined their lives were slowly destroying them all.

The fire changed that – for a while, anyway. Like extreme heat used to cauterize a wound to stop it from bleeding, the fire stopped the slide. It cauterized the downward motion. In time, however, the motion started again, as the social problems from before the fire once again began to drag them slowly downhill again.

In this section, we examine how the social problems we’ve talked about individually intersect for people and populations.We’ll look at how problems of harmful drug use, mental health challenges and rural living complicate disaster recovery.We’ll apply lessons of houselessness and class. We’ll take a closer look at how politics and race make a difference in recovery. In section We’ll examine how climate change makes recovery challenging Finally, we’ll the story of how COVID-19 made things more difficult, but also encouraged us to innovate.

11.3.1 Harmful Drug Use, Mental Health, and Living in the Country

Recovery is a complicated process. Aside from the emotional trauma, there are literally dozens of programs and people a survivor must interact with. From the day their home is destroyed, numerous timers start counting down to deadlines that must be met. Failure to meet those deadlines can result in tens of thousands of dollars of lost financial aid and lost access to other support services.

As we’ve already discussed, for many people in Otis, daily life was already a struggle. Whether the result of an incomplete education, minimal access to the internet, or the struggles we’ve already seen many seniors face, this process is often terrifying, given the consequences for failure.

For people like Carol however, it was even harder.

Long-term drug misuse decreases a person’s ability to think clearly (Carpenter 2001) Among those abilities particularly impacted is the ability to make decisions, the very decisions that need to be made as someone struggles to apply for assistance, meet deadlines, and navigate the recovery process you just read about. This is even more tragic when you consider that this inability to think properly about one’s own recovery creates a personal stress that makes one more likely to relapse into active engagement in their substance use disorder.

As you might expect, this process was incredibly difficult for Carol. From the first moments when she evacuated and for months thereafter she found herself simply going where people told her to go. First to one evacuation site and then to another. When she heard about extra food being delivered to the Church of the Nazarene, she’d get there as quickly as she could. She couldn’t carry much, but not much would fit in her tiny hotel refrigerator, either.

Her recent life of living on other people’s couches had left her unimpeded by needs beyond those of basic shelter and food. Even when she moved into her final hotel, these few things she had to do became a routine she had basically been following without question. As difficult as this may sound, however, it was what this routine didn’t require her to do that was helping her. She wasn’t worrying about having to survive.

The hotel routine meant no more looking for someone who would take a hundred bucks so she could crash on their couch every night. No more worrying if her abusive ex-husband would find her – or worse try to bring her back to his home. For the first time in as long as she could remember, she could focus her energies on her own recovery, instead of her near constant battle to not engage with drugs.

She truly felt she was getting better. She gained weight, her skin began to clear up, and she even began to develop a community of friends that welcomed her beyond her ability to come up with $100 monthly. It would be wrong to say she broke free of her addictions. She relapsed from time-to-time. Some thought she was using meth again. She said she would have periods where she simply drank too much wine. But she was recovering – until it was time to make decisions.

By the spring of 2022, Carol was told she had to make some decisions.The largest was where she wanted to move. Her time in the hotel as post-fire housing as provided by the state of Oregon was running out. She needed to decide where she wanted to go. But she couldn’t decide. For months, this inability to make decisions went on. Carol’s looming decision about housing was the largest she needed to make, but there were others: what type of job she might find; did she want to keep her cat or not; did she want to stay close to the world she knew, or go somewhere else entirely?

As the winter of 2022 became the spring, however, I began to see the stress brought on by years of fighting addiction and then succumbing to it take a toll. It was clear Carol needed help – and as fate would have it, I was the one who could provide it.

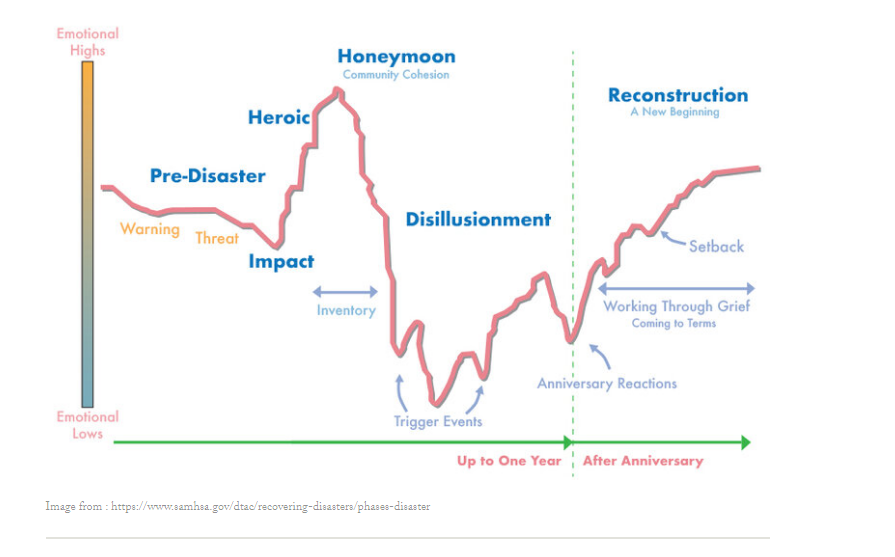

Figure 11.9 Stages in Disaster recovery, Based on Zunin & Myers Stages of Disaster Recovery Model. Pubic Domain. Figure 11.9 Image Description

From almost the moment EMFR decided to move beyond fundraising and start engaging in overall community support and recovery, we’d known there would be a mental health crisis coming. In even the earliest meetings with state and national experts in disaster recovery we’d been told the fire survivors in our community would face a set of known mental health struggles (Turner 2021). These struggles would range from dealing with the shock and impact of losing everything they owned to disillusionment with the recovery process. We would face the trauma caused by triggering events, such as news of other wildfires or even anniversary observances. The model in figure 11.9 shows the highs and lows that social scientists and recovery professionals use when they support individuals and communities in disaster recovery.

Accordingly, through EMFR, we used a contract with the state of Oregon and a $15,000 donation from the Red Cross, to make sure funding was available to pay for people like Carol to get counseling. Our plan was straightforward. For anyone who had insurance, we’d connect them with a provider, and even make the copay if they couldn’t afford it. For those without insurance, we had hired someone whose previous jobs included getting the uninsured signed up for the Oregon Health Plan. Again, whatever costs they might incur after that we’d pay for. Finally, if people couldn’t be assisted through either one of those, we’d pay the entire bill. All the mental health provider had to do was send us a bill. It was a perfect plan, except for one thing – we could not find a single provider.

Figure 11.10 a and b Media for the Art of Healing Groups for Echo Mountain Fire Survivors. CC-BY-SA 4.0 Kimberly Puttman, Figure 11.10 Image Description

Figure 11.10 a and b Media for the Art of Healing Groups for Echo Mountain Fire Survivors. CC-BY-SA 4.0 Kimberly Puttman, Figure 11.10 Image Description

Even with thousands of dollars at our disposal to spend on mental health services, there were no mental health professionals available to hire.

So, we rolled up our sleeves and created services. We funded numerous art therapy workshops for survivors, some of whom continued for over a year. Some of this advertising is show in figure 11.10 a and b. We also helped connect people with other mental health outreach efforts in the community, such as Camp Noah, a resiliency program for kids impacted by disaster. In the summer and fall of 2022, as the Spiritual and Emotional Recovery committee grew larger, we began to pay for other group counseling events. Many of these events were meant to help the volunteers as well, who were feeling their own mental traumas from nearly two years of helping others.

In the end, however, all we could really do for individuals was make sure what little was available would continue. We donated the $15,000 to Lincoln County Community Health to support the ongoing employment of the mental health outreach worker from Community Outreach and Recovery Education. Based at The Grange, she had been working with fire survivors in the Otis area for more than a year at the time we committed to the donation in the spring of 2022.

She was brought on board to give fire survivors someone to listen to them. Despite her background in mental health, she was not a trained counselor. She told people this – and for most it didn’t matter. They valued her simply for her ability to listen, and when she could, help them navigate what government and nonprofit resources were available.

In the spring, Carol even went to see her, when the CORE worker visited the hotel. They made some progress, but the outreach worker was candid with me. There wasn’t much she could do. Carol needed help she simply was not trained to provide. When Carol was asked to leave shelter, she ended up leaving Lincoln County. All the outreach worker could do was wish her well – and call me to say that she had left.

11.3.1.1 Mental Health For Rural People

In the preceding paragraphs we’ve established that:

- Otis already had far more people with substance use disorders than other communities its size.

- Nearly every medical and mental health authority, from the Mayo Clinic on down, lists stress as a leading intersectional cause of harmful drug use

- Losing everything they owned would mean a stress unlike any of them had ever faced.

We knew this. It’s why we fought so hard to get counseling for people and why it still stings so badly that we failed.

Again, however, this failure might have been predicted. The national shortage in mental health professionals is ongoing. . It’s estimated that in rural areas, nearly two-thirds of counties do not have a psychiatrist, while more than 60 percent are known to have a shortage of mental health professionals.

In Lincoln City, even the mental health health practice I had personally connected with in 2017 was gone by the time I tried to hire them in 2022. The counselor that I miraculously was able to hire to deal with the death of a family member in 2021 didn’t have a single opening by 2022. None of the other doctors in their practice did, either, despite having just hired a new counselor in the month before we inquired about hiring them.

Even when there are people to hire, many Otis residents have another problem, common to people in rural areas, as we’ve discussed in chapter 8. Both before and after the fire there were no formal mental health services of any kind in Otis. This means even when help is available, it’s about 10 miles away.

For many people, this might not sound like a long distance. It’s not, if you have a car. Otis residents are 75 percent less likely to own a vehicle than even the average Lincoln City resident. Meanwhile, the local transit system makes only four trips a day to the Otis, with pickup and drop-off times nearly four hours apart. Finally, the closest bus stop to many Otis residents is a half-mile to a mile away, if not further. Even when mental health care is available, many Otis residents can’t get to it.

Ironically, the fire improved this situation somewhat. Following the fire, the county’s CORE mental health outreach worker started working with survivors at The Salmon River Grange. As noted, however, her education, experience and ability to help are often limited. Still, for area fire survivors whose only access to local services may be the trip they take to access the food bank at The Grange, it is an improvement.

Carol, of course, isn’t the only of our five stories to intersect with addiction. Indeed, among our five fire survivors, in the end only one – Fernando – wouldn’t be impacted in some way by substance use disorders. As noted, Tommy had been trying to help his daughter, Wendy, with her disorder nearly her entire adult life to no avail. Even Betty was profoundly impacted by a substance use disorder, though not in the immediate way Carol, Wendy, or even Tommy had been in the weeks and days prior to the fire.

Betty never engaged in drug disorder behaviors herself. Her second husband, however, who had died only a few years before the fire, did have an alcohol use disorder, which resulted in abusive behavior towards both Betty and her adult children. After years of this, Betty’s children chose to no longer bring themselves or their families into this environment of abuse. They made Betty choose between them – and she chose her husband. In the years since his death, Betty had tried to rebuild the relationship with her children. But other than short phone calls a few times a year, there was no contact nor relationship between them.

This gave Betty a lot of time. Like her neighbors, she loved the sound of the wind in the trees. More than most, she treasured the sounds and sights of the birds and wildlife. With her limited mobility, they were among the only connections she could maintain with the world outside her door. Most often she looked out her window, though if Otis’s rainy weather stopped long enough to allow it, she’d go out and sit on her favorite bench. On those days, she’d often get visits from her neighbor. They’d talk for a while, about the birds, the weather, and sometimes even choices Betty had come to regret – some more than others.

But then the fire came, and it was all gone. The birds and the animals she watched from there, the wind in the trees – even the trees themselves – they were all gone. Only the bench remained, surrounded by blackened trees and piles of twisted steel and melted aluminum that used to be her home. She would have to start over at the age of 82. She would need to start the process of recovery, without even her neighbors.

On the most difficult days Betty cried a lot COVID prevented me from giving her a hug – usually. For on the hardest days, when she’d tell me she worried she would die alone in a hotel, it was not enough for me just to tell her she wouldn’t. I wanted her to feel me say it, too. Even then, however, her reality stayed the same: The neighborhood was gone. Everyone was gone – and Betty had never felt so alone.

11.3.2 Social Location: Harmful Drug Use

Drug use statistics are hard to come by

Statistics about drug use, particularly those specific to community level can be difficult to both create and find. Drug use is not tracked via the US Census, nor is it usually among the most common forms of demographic data. Certainly, national data on specific types of drug use is available. This type of information, however, is not broken down enough to let us compare Otis to Lincoln City or the county as a whole. This is not to say there is no data that can inform us about drug use within Lincoln County.

For instance, information is available on legal opioid drug use, as prescribed by a doctor. In the most recent information available via the Lincoln County Community Health Assessment (LCCHA), nearly 32 percent of residents had gotten an opioid prescription. This rate is 10 percent higher than the state as a whole. Certainly, not every person who receives opioid prescriptions becomes addicted to them. The link between opioid addiction, as well as addiction to other drugs, however, is solid.

As we discussed in Chapter 8, a range of studies suggests approximately 10 percent of those prescribed opioids will become addicted to them. Three-quarters of the people addicted to opioids report their addiction to opioids started with a prescription. The number of heroin users reporting that they used prescription opioids prior to heroin use was 80 percent. If we use these figures to estimate harmful opioid drug use in Otis, there would be more than 100 opioid addicts among Otis’s 3300 residents. Intersectionality suggests the number is even higher. According to the Mayo Clinic, poverty, and heavy tobacco use also contribute to an increased likelihood of becoming addicted to opioids.

In the end, we knew this. That even among all of those who had been through a disaster like the Echo Mountain Fire, there would likely be another two dozen people who were at even greater risk. As it turns out, it was more than a possibility.

11.3.3 Houselessness in a Tourist Town

As noted earlier, Carol spent a lot of time away from her legal address, a storage area on the edge of the property owned by her ex-husband. As a result, she might not be what you typically think of when you create images of homeless people in your mind. She was not sleeping in a tent under a bridge or pitched on a sidewalk next to the road, as is so often seen in many of America’s cities right now. Instead, Carol was staying with friends, usually on a couch, sometimes in a spare bedroom. This matters, because regardless of what the government definition is of homeless, which we looked at in Chapter 4, Carol did not consider herself homeless. Interestingly enough, her community did not, either.

That’s why throughout Otis it was not unheard of for long-time residents to let people pitch a tent in the woods beyond their home as a way of doing what they could to help.

Tommy’s daughter Wendy had been one of those people years earlier, though she’d long since moved away. Over the years, her dad had begged her to return, so he could get her the help she needed. A few weeks before the fire, she finally agreed. Even better for the both of them, he’d been able to make arrangements with his buddy to move his daughter home – on what turned out to be the day of the fire. Tommy’s friend was on his way west back to Otis from Salem when the road was literally closed 20 miles ahead of him because of the fire. That he wouldn’t have a home for either of them within 24 hours was tragic. That this bad timing would in the end prove to be the most critical part of Wendy’s recovery story, is even more so.

Because Wendy was not technically residing with her father on the day of the fire, she was not eligible for government assistance as a resident of Otis. That she had plans to move in, that she was even actively in the process of moving her things to Otis, did not matter. Wendy was one of those that FEMA considered her “pre-disaster homeless” and told her she was ineligible for help. Neither she nor Tommy knew this right away, of course. When they were eventually reunited at a fire evacuation hotel in Lincoln City in the days following the fire, both of them listed his address in Otis as their legal home. For nearly a year, they both progressed through the fire recovery process as two separate cases, with both receiving housing and food.

During this time, however, interviews began with Disaster Case Managers hired by the state of Oregon. During intake interviews, they would ask survivors questions about what aid people required to get back to the lives they once knew. Most of them were basic, demographic questions, with two always among the first: “What was your legal address at the time of the fire? Were there any other family members living with you at the time of the fire?” Wendy told them she lived up Panther Creek, with her father. Tommy told them he, too, lived up Panther Creek, alone, with his daughter having been scheduled to move in on the day of the fire.

The Disaster Case Manager interviewing her noticed the discrepancy in their stories. She returned to Tommy and asked him to explain the difference – but first they told him why it mattered. They told him that if she had not been living there, that Wendy would have to leave the hotel where they both were living. They told him that all of the assistance she had been getting would end. They asked Tommy to be very sure of what he told them next, and even gave him a few days to think about it.. If he said she’d already come home Sept. 7, she could stay. If he said she’d been in the process of moving home Sept. 8, she would have to leave. He would not lie.

Three days later Wendy moved out of the fire survivor hotel. The community that she’d helped move into the building now helped her move out. Packing every last thing she could fit into her car, even the front passenger seat had things in it. She wasn’t sure where she was going to go, she told her friends wearily.

As she pulled out of the hotel parking lot, her bumper was only a few inches off the ground, the weight of her things and the springs in her car’s rear suspension seemed as tired as she was. I was hoping at the very least she’d stop by The Grange as she left town.. They knew her, and they knew her dad well, as well as everything he’d tried to do to help her. They had some things they wanted to give her, and they wanted her to leave her contact information with them, too. They were to the right and just 10 minutes away.

When the light turned green she turned left. “I guess she’s headed down to Newport,” said one of her friends. “I think she’ll be dead within a week,” said another, though thankfully her father wasn’t there to hear it. He was in his room, still thinking about the lie he could not tell.

Carol, too, was starting to answer questions about her legal address at the time of the fire. As explained earlier, Carol ultimately left the fire survivor hotel because she was unable to make decisions about what she wanted to do. What it took her to even get to this point, however, is worth explaining as it relates to government aid and what we often force people to do to receive it.

Unlike Wendy, it was not verifying a date that would determine what aid Carol received. Instead, it was verifying an address. Carol had no proof that she’d lived in any specific place in Otis. Yes, she’d been in Otis for years, but in the year since her divorce, it had been largely spent on couches. Many of the people Carol “rented” from were renters themselves. Government regulations do not allow paying rent to another renter as a legal form of establishing an address.

There are other means of establishing residency at a particular address for government purposes. They will accept the name on a utility bill, such as water, power, or even cable television. Carol had none of these as a renter. She had her name and an Otis address on her driver’s license, as well as proof that she’d registered to vote using that address. None of those were good enough, however. Unless the driver’s license had been issued in the previous 90 days before the fire, she could not prove she hadn’t moved from that address. Voter registration, too, was meaningless. While Oregon’s voter registration laws are known as some of the best in the country when it comes to encouraging people to vote, their very openness makes them useless for proving residency.

Very simply the only way Carol could prove – the only way most Otis residents could prove – they had actually lived somewhere at the time of the fire was to prove she’d spent money doing so. Using nothing but cash transactions and never staying in one place for long, Carol had no evidence she actually lived anywhere.. o Carol’s abusive ex-husband eventually signed and notarized a document stating that Carol had lived on their property. This document is proof of a lease, putting a monthly monetary value of $100 on the yardwork that Carol had done. Once the Disaster Case Manager received the document, .Carol was allowed to stay in the fire survivor hotel.

That so much of the recovery process boils down to how much money they spent, when and where is infuriating to me. In all fairness to FEMA, their willingness to accept a simple letter months after the fire serving as the equivalent of a lease was not something they had done in previous disasters. This was something relatively new to them, reflecting the very real housing crisis that many Americans in disasters had been dealing with prior to the fire, hurricane, flood, or whatever other crisis had befallen them. I give them full credit for that.

Indeed, if I am being fair, I cannot even begin to name the number of people I know in Otis who were economically saved by such an arrangement. Their casual living arrangements were allowed retroactively to be defined in a monetary means that, while perhaps objectively factual, were likely never seen that way by the people involved. That there was some “re-imagining” of the past seems inevitable – and FEMA accepted it. Still, it has to be asked how many people were left out.

What about families who know all too well what it means when the government tells you one thing, and then does another? Are you going to feel comfortable telling them anything that seems even remotely like it would hurt you?

Absolutely not – as Fernando would assuredly tell you.

11.3.3.1 Houselessness by the numbers

Like levels of addiction, the size and seriousness of the homeless problem in Otis can be difficult to examine statistically. This isn’t just true because Otis is small. Even in the largest cities, both government and nonprofit groups involved in counting the homeless will confirm that accurate counts are difficult within a city and/or county. Again, however, Otis is statistically different from the rest of the county, and even nearby Lincoln City. Therefore, once again, a quantitative understanding of the situation in Otis will need to be created by looking at a variety of sources that at least identify part of the problem.

According to a 2020 study conducted by the Community Services Consortium serving the tri-county area of Linn, Benton, and Lincoln counties, Lincoln County’s homeless population was approximately 1.9 percent. This number is smaller than a 3.5 percent average statewide, but approximately double that of nearby Linn and Benton counties. The statistics within the population of people within Lincoln County reporting themselves as homeless is also different from its two neighboring counties. Approximately 69 percent more people report being homeless more than four times in Lincoln County. Even so, a higher percentage of Lincoln County’s population considers themselves recently homeless as opposed to chronically.

Here, race intersects as well. While White people make up nearly 90 percent of the population of Lincoln County, they make up just over 82 percent of the homeless population. Native Americans make up the largest share of homeless people as compared to their population: 4 percent of the overall population, while their share of the homeless population is more than double at 8.2%. There is no way to know if these racial numbers – or any of our homeless data for Lincoln County – are vastly different in Otis.

An exact count of how many pre-disaster homeless resided in the Otis area has never been created, therefore the true magnitude of the problem remains undefined. This is part of the problem. Exactly what defines someone as homeless as depends on who is writing the definition.

The CSC report interviewed and tracked homeless individuals on the street and in shelters. The U.S. Census defines these individuals as homeless – along with those temporarily staying with family or friends, or living in a car or recreational vehicle (RV). The Lincoln County School District defines homelessness simply as students who lack a fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence, as do most school districts in Oregon. These definitions make a difference.

For example: while the CSC survey shows the homeless population of Lincoln County to be 1.9 percent, the school district shows 11.8 percent of their students being homeless. These numbers change from year to year, but in most years, the Lincoln County School District has the highest student homelessness rate of any school district in the state. Many of these types of students, based on the fire survivors who engaged with EMFR, lived in Otis.

None of these definitions of homeless are “wrong.” Different surveys are conducted for different reasons. Also, even within one definition, there can be a tremendous amount of change when it comes to the living conditions of one individual. A student who sleeps in a shelter one night and then couch surfs on another may or not appear on the CSC survey, depending on the time it was taken. Within the school district definition, this student’s mobility would have no impact on the final count.

Of course, even if someone had been sleeping on someone’s couch for months, if they could not produce a lease saying they were renting that space, they were ineligible for aid. People who may have been staying at someone’s home, their name never appearing on a utility bill or other documentation that could be verified as connected to an address, were ineligible for aid. At times, this FEMA definition of pre-disaster homeless reinforced both structural misogyny and racism.

Women who may have left an abusive relationship, with no legal name on any of the home’s utilities or legal documentation could be denied FEMA assistance. Hispanic households, who may have had multiple families under one roof, found that the family whose name was on the lease could get help, while the other could not. Local fire-relief groups, such as EMFR, tried to step in and mitigate these issues within the FEMA relief framework. Sometimes they were successful. Indeed, this definition would prove to be the most meaningful one for many Otis residents following the Echo Mountain Fire, those who would ultimately need the Disaster Case Grange-ament program.

Other times, however, abused women, undocumented Hispanic families in fear of deportation, and other vulnerable populations were too scared or traumatized to make use of this assistance. As a result, ironically, some Otis residents who did not consider themselves homeless before the fire, now truly were. A situation that was created largely because FEMA’s definition of homeless made them ineligible for aid.

Finally, even within those statistics that suggest someone’s homeowner status would protect them from homelessness, there are surprising statistics. For instance, according to information gathered by EMFR, just shy of 70% of the homes burned in Otis were owned by their residents. Of these residents, however, only 69 percent of them were insured. Of the remaining 31 percent were dozens of families who could not get insurance because of the age of the modular home in which they were living.

It is estimated across Oregon that more than one-quarter of the modular homes in use are so old that insurance providers will not insure them. In Otis, where 90 percent of the homes that burned were modular, that would mean 60 to 70 families who went from home ownership to owning nothing literally overnight. Certainly, many government programs were available to help these homeowners.

11.3.4 Political Divides Contribute to Social Problems

Fernando was more fortunate as he prepared to seek resources to move forward. His previous work with the county gave him some familiarity with governments and how they worked. Still, he did not know how to start. That thought alone cost him hours of sleep. There was also sadness, depression and anxiety. The truth for him was as it was for every survivor: it is not easy to start again from ashes, to materially create a home again. It is not easy to get up each day when you have no idea if any government agency – anyone – would be there to help you and your neighbors in a small, devastated town.

Amidst these sleepless nights and uncertain thoughts, he discovered something else, however. That not only could he not stand still or wait for help. But he must also have the courage to seek help so he could help the rest of the Latino families like himself return home. This was his distraction from his depression and sadness. By staying focused on finding resources not only for himself and his family, but for the entire Latino community which had the least amount of help, he would find his motivation to get up each day.

This is what would guide Fernando through the next two years. Journeying from his own devastating experience, Fernando was able to keep his faith as he moved forward for he and his community. A journey that would connect him with generous people he would have never otherwise met. Grateful that an experience that began in tragedy would ultimately show him that after the darkness there is always a light of hope.

I should at this point note what I, as a white, upper-middle class, transgender woman, know about the Latino community is only that which they have chosen to share with me. Yes, I know the overall demographic statistics about the community itself. Which is why I knew the recovery was more than likely going to leave them behind as a community – even before FEMA owned up to it.

Whatever the case, from literally the first moment the fires began, the political discourse that had been accelerating against people of color since the election of 2016 was on full display.

In one community impacted by Oregon’s 2020 Riverside wildfire, a long-time resident and local journalist feared for her life when she found herself labeled a threat. Some people had overheard on the radio that “BLM” – the Bureau of Land Management – was seen in the vicinity of the fires. Assuming instead that BLM meant “Black Lives Matter,” the narrative on right-wing websites and social media soon had “Antifa terrorists” lighting forest fires all over the Pacific Northwest – and threatening the journalist who’d “started” them.

Closer to the concerns of the Latino community, local nonprofit and government leaders had become aware of a concerning incident in Jackson County. The location of the Almeda Fire, 2,600 homes were destroyed, most of them belonging to Latino families. In the very first days following the fire, local nonprofit organizations stepped up to provide meals and water to displaced families, and they welcomed any volunteer who would help. Among those who answered their calls for assistance were members of Immigration and Customs Enforcement. It is not known what their intentions were, but the fact they kept their badges and occupations hidden was enough that they were asked to leave when someone discovered who they were.

Perhaps that’s why, even as White families in Otis were comfortable with “re-imagining” and then telling FEMA about the casual living arrangements they had with other family members, some Latino fire survivors chose not to. A choice that meant no access to up to $7,500 in immediate aid, to say nothing of tens of thousands of dollars in long-term aid.

On its surface, this might seem surprising. Latino families are more likely than White families to live in multigenerational households (Landale et al. 2006). It is also not uncommon for adults from the same generation and their children to live together, siblings and cousins all sharing and contributing to the same household. FEMA rules, as traditionally enforced, basically meant anyone not living in a “traditional” family of parents and children stood to lose out – and as often was the case, this hurt people of color more. Now, however, families of all kinds, especially those of color, would be able to explain to the government that intertwined in these households was an embedded, if unspoken, financial arrangement. This, it seems, is something that would help Latino families.

What these Latino families could not ignore, however, was reality. Whether that was what they had seen happening socially Otis, or heard of with ICE in Jackson County. To trust the government with the identities of which family members lived with whom, especially those who are undocumented, was simply too big of a risk.

Did Fernando know of people turning down aid? Would he even feel comfortable suggesting they “re-imagine” things as so many others were? We never talked about that, either. When he came to The Grange in the earliest days of fire relief, he often did two things. When he arrived, he usually brought items from the store and used The Grange’s kitchen to make lunch for the volunteers. Before he left, he got a copy of every form he could in both English and Spanish to give out to his community.

From this account, it might seem that the increasing political polarization was in Otis, too. That as it was in the rest of the country, fire recovery would be increasingly fractured as the 2020 election approached. A largely White town, divided along educational, economic and even religious lines, each side increasingly less accommodating and understanding of the other. But that’s not what happened at all. The Volunteer Clean-up was indeed born of diversity, pictured in figure 11.11.

Figure 11.11 We come together even though we are different (Fair use)

“The Volunteer Clean-up” – its description would ultimately become its proper title – started with the local minister of an evangelical church who was also manager at a local landscaping company. With those tools and heavy equipment to get the work done, he asked those homeowners near him at the bottom of Pony Trail Lane if he might help them out, too. Pony Trail Lane was a small loop road on the slopes of Echo Mountain. Every home on this road was destroyed. There were plenty of people to help. Many of them were not Evangelical Christians, while others wouldn’t apply “Christian” or even particularly religious to their identities.

Still, enough said yes that the minister began to invite other community assistance groups, each of them affiliated with other churches in the Pacific Northwest. Some of them brought heavy equipment of their own, while others brought along portable kitchens and food to feed the volunteers during the increasingly cool days of fall.

Within days, the minister and his volunteers were joined by others, and more neighbors had their lots cleaned. Among those who came to help was the leader of Cascade Relief Team, a Black man from the Portland suburbs, helping bring needed supplies to the clean-up. Members of The Grange were there, still at this point largely seniors, bringing out what supplies they could. An LGBTQIA+ journalist and activist came to help generate more donations to keep the machines fueled and people fed. (That was me.)

Fire survivors came, too. Some were leaders, like the president of The Grange, who had lost her home in the fire. Others had no affiliation. They just wanted someplace to go and feel like they were helping others, even as they could not help themselves. So many came, that the effort was able to grow beyond cleaning up the small group of homes at the bottom of Pony Trail Lane. Everyone was welcome – which was good, because everyone was needed, as clean-ups were now starting in other parts of the burn zone. New leaders emerged, and other equipment was brought in, even as the minister and the first group of volunteers had to return to their jobs. Off of Pony Trail Lane, one of the first home sites to be cleaned up was Fernando’s. The leader of the crew was wearing a “Trump 2020” hat.

In the end, the effort cleaned nearly 100 lots at no required expense to fire survivors. Tommy and Wendy, as well as Betty were among those property owners. What the volunteers accomplished was more than cleaning. It had the potential to be life-changing. For Betty and Tommy, this collaborative and accelerated process meant they were able to sell her properties far sooner than would have ever been possible. Betty was even able to pay off all her back taxes, giving her both time and resources to choose what she would do next. For Fernando, whose lot was among the first to be cleaned, it gave him a clean piece of land on which to place a trailer. One that held the entire family, he basically got a six-month head start on getting out of the motel and rebuilding his home.

While every other community in Oregon was waiting for the government to arrive to begin their clean-up so they could begin their effort to get home, in Otis nearly one-third of the families who’d lost their homes were already able to begin. The Volunteer Clean-up even got some of its leaders featured in national news (Flaccus 2021). In the Willamette Valley, nearly a dozen stories ran in the local papers or on Portland TV stations. Each one reminding people that people of Otis still needed help, starting with financial support to the Volunteer Clean-up.

At Christmas, the leaders of the Volunteer Clean-up even hosted a Christmas party, featuring a hot food buffet and Christmas gifts for the kids. Each person who attended realizedthat what they’d all created on that mountain, was indeed a gift.

Remember, however: this story began with a discussion about racial relations in Otis had been changing since 2016, and indeed building across the country as the 2020 election approached. The Volunteer Clean-up, the Christmas party, the attention these efforts gathered: These were not just a distraction from national events. They countered it, even as divisiveness continued to grow in the country. For even as a contentious national election wrapped up, a mob invaded the U.S. Capitol, and another impeachment trial began, the people of Otis stayed together. As one story put it: “A minister, a black guy, a transgender chick, and a Trump supporter walked into a town… to help save it. (Denis 2020:n.p.)”

This is not to say everything went perfectly, nor that everything is now. Efforts to have Latino community members feel like The Grange was a place where they could find assistance have been difficult to nourish and develop. Long before 2016, many Latino families found Otis a challenging place to live. Drawn to the area for many of the same reasons of space and economics as White residents, these similarities weren’t enough to make them neighbors and friends. Trump flags and chants of “send them back” may have gotten bolder and louder following 2016, but the sentiments had been there for decades, and they still are.

11.3.5 Climate Change Comes to Otis

Figure 11.12 The sign for Chinook Winds Casino. Other signage was flattened by gale force winds. The sky was hot, orange and full of smoke from the Echo Mountain Fire.

It’s easy to say something is “The World’s Largest Problem,” but it’s often hard to defend the statement. Making such a statement about climate change isn’t difficult. The problem literally affects every human being on the planet.

In north Lincoln County, however, the problem doesn’t need to be illustrated with a world of statistics, or even a national map. Environmental justice, which we learned about in Chapter 5 doesn’t require that we look at state impacts or even changes within the county. Like everything else in this chapter, we can see it on Echo Mountain, and in the lives of the people that live there – and once did. Unlike the rest of this chapter, however, we’ll start this part of the story at the end.

The summer of 2021 was Oregon’s hottest on record. A heat wave that year shattered records across the state, with Salem hitting 117 degrees in June, the hottest temperature ever recorded in the Willamette Valley. On the coast, however, temperatures barely broke into the 70s, and most days saw highs in the upper 60s, with Otis close to the same. The summer of 2022, however, did not spare Otis, with temperatures reaching into the 90s (Accuweather 2022) For hundreds of Otis residents who’d returned home in the last year to live in new manufactured homes and trailers, the temperature inside their homes could reach over 100 degrees. Miserable to be sure, but how is this an injustice?

Environmental justice can mean access to shade. For those living in trailers in the unshaded sun, Googling possible solutions to the problem offers this: “park in the shade.” In Otis there was no shade for these new homes. Every tree that had provided such protection had been destroyed in the fire. Even in the midst of the Oregon forest, with its lack of tree cover, Otis was now like many communities with low SES, with 25 percent less shade than more typical communities.

Environmental justice can mean access to cooling. Air conditioners were also in short supply, as they are for most people with low SES. Across the country, more than half of residences with low SES occupants have no air conditioning – and those statistics are for the nation (US Energy Information Adminstration 2011). In Otis, where high temperatures even in the summer rarely break out of the 60s, the number is likely even lower. A lack of air conditioning may strike many as a “first world problem,” but it is in fact a fatal one for many. Oregon’s 2021 heat wave killed 116 people across the state, the vast majority of them people over 60 – the same age as many of Otis’ returning residents.

Again, is this the typical definition of environmental injustice? It is not. What made these residents’ homes so hot were not unfair environmental laws, regulations, or policies. It was that a wildfire, likely related to climate change, burned their shade to the ground. The middle-class and the wealthy residents lost their shade, too. Without question, however, low SES played a role in how Otis residents were impacted by the increasing heat in 2022. Their wealthy neighbors had air conditioners.

We see more typical environmental injustice when we look at Betty’s story more carefully. Suffering from COPD, Betty’s daily life in Otis was impacted in numerous ways that tied into her low income. She lived on a dirt road, the dust making it difficult to breathe when a car drove by as she sat on the bench in her garden. Her decades-old mobile home let in the dust no matter how tightly she closed the doors or windows. Even before the fire, Betty’s house wasn’t healthy.

Then the fire and all the smoke came. We can see the devastation of wind and smoke in figure 11.12. By the time Betty evacuated, she had been breathing smoke for hours. As Betty fled her home, she could barely see outside to reach her neighbor’s car. As they headed out, there was no setting on the car’s vents that could keep out what Betty was breathing into her lungs. She would say later she could almost feel the smoke attacking her COPD-damaged lungs.

Betty was not alone in this regard. Certainly, for someone with COPD and other respiratory conditions, wildfire smoke can be fatal. For the elderly in general, however, along with children and people with pre-existing health conditions of all kinds, wildfire smoke can cause serious illness (D’Evelyn et al. 2022). Indeed, when scientists look at those populations most impacted by wildfire smoke across the nation, it reads like a description of Otis: “Populations more vulnerable to smoke exposure include people in low-income communities, people living in homes with poor air filtration systems, (and) people experiencing homelessness.”

Figure 11.13 The greenhouse and the Fall holiday celebration at Landscaping with Love. Small, sustained efforts can create environmental justice.

Just a few lots down from Betty’s old garden, however, a new garden began to rise in the winter of 2021. The president of The Grange set aside a piece of her property for what would become an example of environmental justice unlike any in the 1.1 million acres of burned Oregon. They called it “Landscaping with Love.” Within a matter of months the site held a greenhouse, as shown in Figure 11.13. In the greenhouse were vegetable seedlings and other baby plants for fire survivors. Next to them were gardening tools of all kinds – everything from spades to wheelbarrows – and books on how to use them.

Outside were more plants, everything from the smallest flower, to a sprawling rhododendron bush, to sapling trees. There were even pre-assembled garden boxes, and demonstration gardens in a few of them. Each variety of plant was chosen not just to demonstrate what would growbut also to show how people could replant their yards and make them more fire resistant in the future. All of this was free. If a fire survivor needed help replanting their lot, the services, expertise, tool rental, and plants were at no cost to fire survivors. Fernando took some plants home on visit. Dozens of his neighbors did the same. In this way, not only did Echo Mountain and Panther Creek begin to be replanted with more fire-safe plants and vegetation, but also in a more environmentally sustainable one, too.

Now, was this posted on the door? Was “combating climate change” splayed across the Landscaping with Love Facebook page? It was not. But planting wildfire and drought-resistant plants was doing exactly that. They just didn’t call it “fighting climate change,” or “environmentally and economically fair.” They called it “doing the right thing.”

Here, “#OtisStrong” was built and sustained. In the truest sense, it was for everyone.

11.3.6 If that weren’t enough, COVID-19 struck

COVID-19 came to Lincoln County in the late winter and spring of 2020, By the summer of 2020, tourists were told to stay home. Lincoln City was closed.

Very few public-facing businesses in Otis had to close, largely because there weren’t many to start with. A pot shop and a small pizza place were affected, though both of the mini-markets at opposite ends of the town remained open. But Lincoln City is where most Otis residents work – and now they weren’t working.

On a personal level, COVID-19 had already impacted some fire survivors’ lives in ways that might have gone unnoticed if the fire had not occurred. With money tight, some Otis residents decided to reduce their level of fire insurance, or forgo it completely. What in one month had seemed a calculated decision to save some money for a few months now would impact them for the rest of their lives. Beyond the individual stories, however, the presence of COVID-19 also played a massive role in both the immediate and ongoing response to the fire. For those who would lose their homes in the fire, this would be especially true.

Prior to COVID-19, disaster response normally entailed placing displaced residents into “congregant living facilities,” such as cots in gymnasiums, or sleeping bags unrolled on the floor at a local church. With COVID-19, this was impossible. Instead, families were booked into area hotels. In this sense, the evacuees of the Echo Mountain Fire were lucky. Lincoln City itself is home to thousands of hotel rooms. With few exceptions many of the local fire survivors could be housed in the hotels of north Lincoln County.

This made an enormous difference.As the evacuation orders lifted, those whose homes had survived could be home in minutes. Survivors who lost their homes only had to travel short distances to work on their property. Even though survivors were often housed together, COVID-19 caused isolation. NSurvivors were discouraged from visiting the rooms of people who were not part of their immediate family. Their former neighbors, life-long friends, might literally be in the same building as them. To stay safe from the virus they could not see each other. Betty, for example, didn’t know that for the first eight months after the fire her former neighbor had been living just two floors below her the entire time. As discussed earlier, this social isolation only made worse the ongoing mental health crisis that was occurring within the population of fire survivors. As a result of both the pandemic and the ensuing job crisis (US Department of Labor 2022), there was simply no one to talk to. Unless they were able to secure counseling or other assistance through their own insurance, they remained without formal individual counseling. One fire survivor, celebrating his 30th birthday, wanted nothing more than just to eat a steak. He couldn’t get one. Every restaurant in town was closed, and there was no open grilling allowed in the hotel parking lot. He was alone – just like every other survivor, in one way or another.

Echo Mountain Fire Relief changed that.

Following a disaster, it’s almost expected that people from across the region and even the country want some way to help those in need. While the Echo Mountain Fire was geographically one of the smallest to erupt anywhere in America during the summer of 2020, by Christmas time it was one of the most well known, at least in Oregon. Our hometown Volunteer Clean-up had put us on a lot of people’s philanthropic radar, and they wanted to help. Churches inside Lincoln City wanted to make cookies, civic clubs from throughout Lincoln County were willing to give gift certificates, donations of toys were collected by our neighbors to the north in Tillamook County, and across the country someone in North Carolina wanted to send quilts.

We knew we needed a Christmas party. It was a small thing with a large impact after all the organizing we’d already done, it would have been easy,- except for COVID-19. Holiday parties across the world were canceled as a result of the pandemic. Festive activities like sharing cookies and drinks could spread the virus. We decided to have a party anyway.

This decision met with controversy. Working together doesn’t mean that everyone agrees. It means that people and organizations continue to work to build community in the midst of disagreements. One of the largest disagreements during this early response regarded our decision to have the Christmas party. To me, however, the decision to have one was simple. And when people challenged me to explain why, I said two simple words: “George Floyd.”

COVID-19, fire relief, #Black Lives Matter, George Floyd, and Christmas parties: these things might seem totally unrelated. But as we discussed in Chapter 6, thousands of people marched in support of Black Lives Matter, even with the virus raging. For some, the need to protest White supremacy and police violence was more urgent than staying quarantined (Diamond 2022)

And in the case of fire survivors, the need to connect and celebrate was more important than the protection of quarantine. That’s why I decided to organize a Christmas party for fire survivors. At the party, I saw fire survivors there I had not seen in weeks. Fernando and his family were there, along with a few other Latino fire survivors. Tommy and his daughter were there, too, as was Carol. Even when I am saddened to think about how Carol and Wendy had to leave the hotel, I take some solace in remembering their smiles that night. I think it was the first happy and community Christmas any of them may have had in years – which of course is why we did it. They needed to know they were not alone. And for one night, they were not (and as far as we know, no one got COVID-19).

11.3.7 Attributions and Licenses for The Interconnected Social Problems of Wildfire Recovery

“The Interconnected Social Problems of Wildfire Recovery” by Bethany Grace Howe is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 11.9 Based on Zunin & Myers Stages of Disaster Recovery Model. https://katieturnerpsychology.com/blog/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-stages-of-disater-recovery https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=4017 Pubic Domain

Figure 11.10 a and b Media for the Art of Healing Groups for Echo Mountain Fire Survivors. CC-BY-SA 4.0 Kimberly Puttman

Figure 11.11 We come together even though we are different Fair Use

Figure 11.12 The sign for Chinook Winds Casino. Other signage was flattened by gale force winds. The sky was hot, orange and full of smoke from EMF Marc Brooks CRT (Matt Brandt) – need permission

Figure 11.13 The greenhouse and the Fall holiday celebration at Landscaping with Love. Small, sustained efforts can create environmental justice. – from facebook, need permission

Image Description for Figure 11.9:

The graphic is described here:

Phase 1: Pre-Disaster is marked by fear and uncertainty. The length of this phase depends on the type of disaster and how much notice there is to prepare. For the COVID pandemic, this phase was marked by panic buying of supplies, preparing for the unknown/the worse, fear and uncertainty and not knowing what to expect.

Phase 2: The Impact Phase: This phase is marked my intense emotional reactions and again depends on the type of disaster. Emotional reactions can range from shock and panic to denial and disbelief. This is often followed by a focus on self-preservation and protection of family/loved ones.This phase is generally the shortest.

Phase 3: Heroic Phase: Often marked by high levels of activity (yet low levels of productivity). Community members often rally to action & sense of altruism is high. This high energy, helping phase often quickly passes into the next phase.

Phase 4: The Honeymoon Phase: There is often a collective dramatic shift in emotion, disaster assistance may be readily available, Community bonding occurs. There is optimism that things will return to normal quickly. In many disasters this phase typically lasts a few weeks.

Phase 5: The Disillusionment Phase: Optimism turns to discouragement. Ongoing stress takes a toll and negative reactions becomes more prevalent (substance abuse, exhaustion, mental health concerns. We are collectively in this phase at the time of this article. It has been over a year and we are into a third wave and increasing restrictions again. Hope is low and a sense of collective low level (or full out) depression is high.

Phase 6: Reconstruction Phase: Overall feelings of recovery. Begin to adjust to new “normal”. Begin to rebuild lives while continuing to morn losses. We have not hit reconstruction phase yet but this phase will come. We will have to process our collective grief and to rebuild. The good news is that collective emotions do begin to rise again.

Hold onto hope, do you what need to do to survive this time, take care of yourself as best you can and know that this too shall pass.

Image Description for Figure 11.10:

11.10a: Flyer publicizing free, somos bilingues The Art of Healing, Relax, breathe and Play for Echo Mountain Fire Survivors, 1) May 12, The art of stories, 2) May 19, The art of mandalas, 3) May 26th, the srt of visions

11.10b: Flyer publicizing Art in the Afternoon, EMFR Purveyors of fun, free Saturday programs for teen and adult fire survivors with an art therapist