2.2 Why is Sociology Revolutionary?

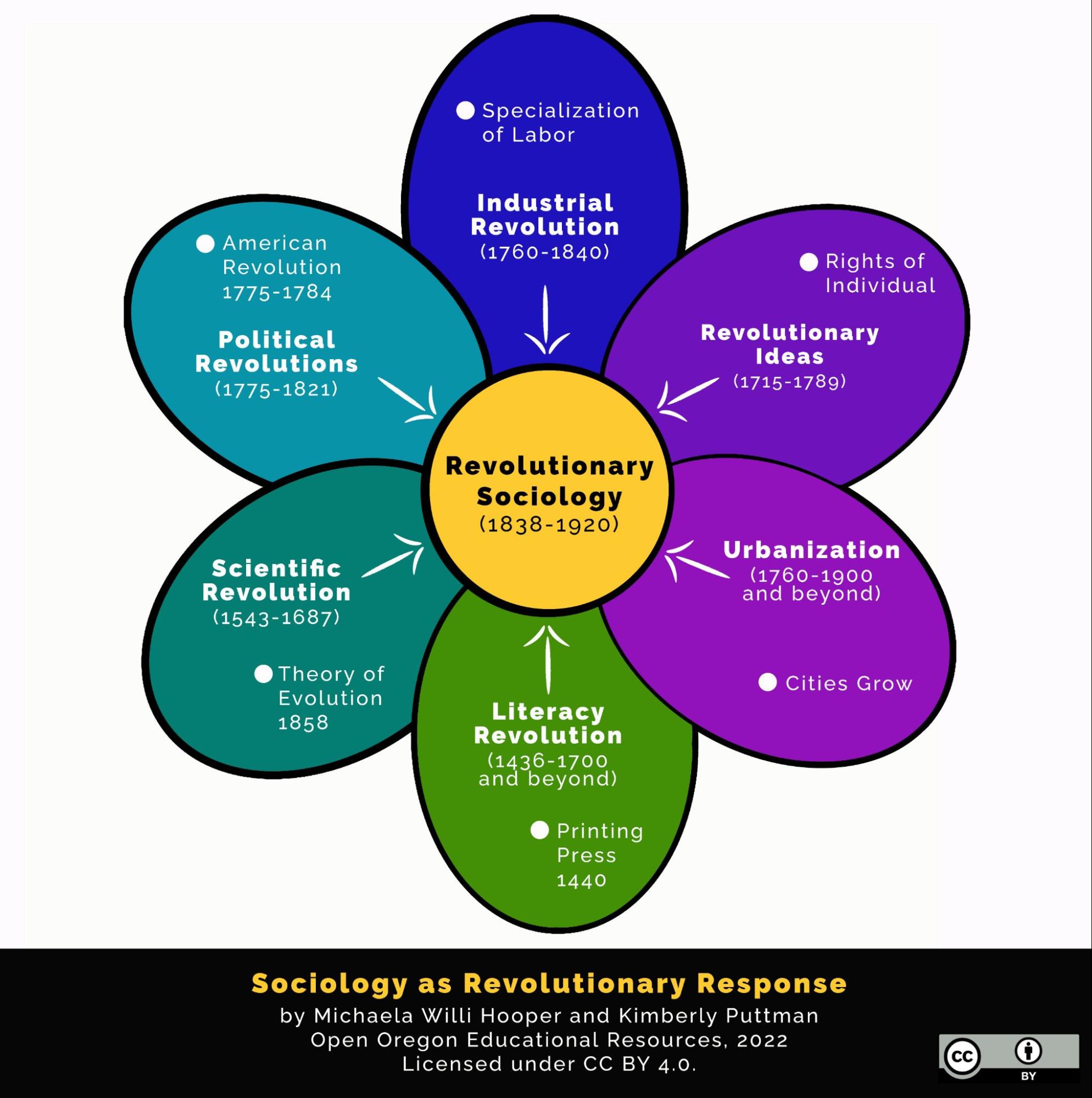

The roots of social inquiry can be traced to many civilizations across time and space. European and American sociology in particular was a radical response to the significant social disruptions of the 1700s and 1800s. The focus on using scientific inquiry to understand and solve social problems arose as an answer to war, famine, and disease, as well as to changes in values, philosophies, and technology. What were these disruptions, and how did they result in a revolutionary response? The chart in figure 2.2 begins to tell the story. We’ll expand the picture section by section.

Figure 2.2 Sociology as a Revolutionary Response. Figure 2.2 Image Description

2.2.1 Age of Exploration and Colonization (1400–1600)

Figure 2.3 This painting romanticizes the voyage of Christopher Columbus. As you look, please consider who was “found.”

People who live in a community ask questions about what it means to live well in groups. Wise people, religious leaders, sages, and scholars have answered them in a variety of ways. Some of the early scholars include Moroccan scientist Iban Battuta, Chinese scholar Du You, and Tunisian sociologist Ibn Khaldun. However, European academic sociology was a radical response to the significant social disruptions of the 1700s and 1800s. But what was disrupted?

In order to answer that question, we need to go back in time to the thirteenth century in Europe, where we see three social forces of politics, religion, and colonization coming together. In politics, most governments were monarchies. Kings (for the most part) ruled their countries because they were part of royal families. They ruled by “the divine right of kings,” the doctrine that God granted the king total control over the country and all the people who lived there.

Similarly, the religion of the day was not only Christian, it was Catholic—specifically the Holy Roman Catholic Church. The Pope was the head of the church, with worldly powers which rivaled monarchs of the time. The Holy Roman Catholic Church maintained its power by means of the Inquisition, a group of policies, practices, and people who tortured and killed people who challenged the “one true faith.”

As power centralized in both church and state in Europe, the monarchs were able to pay for worldwide voyages of exploration. One voyage is immortalized in a children’s nursery rhyme: “In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” We see the voyage of Christopher Columbus in the painting in figure 2.3. As you look, you may want to consider who was “found” during these voyages.

Kings and queens were expecting that the expansion of trade would bring them wealth. Over time, the exploration led to colonization. Major European countries claimed territory in Africa, North America, and South America, shattering the territorial rights of the people who already lived in these areas. Many politicians and business people in Europe began the worldwide slave trade and the genocide of Indigenous peoples.

2.2.2 Scientific Revolution (1543–1687)

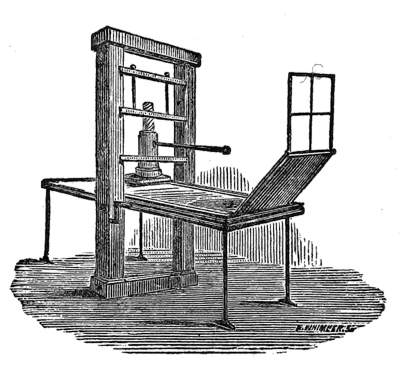

Figure 2.4 Early Press, etching from early typography by William Skeen, 1872

Even though monarchies and the Holy Roman Catholic church remained hegemonic (or dominant) for centuries, two destabilizing forces arose to challenge their power: the expansion of literacy and the bubonic plague.

The first destabilizing force was an increase in literacy, the ability to read and write, in Europe and countries with European trade. Before 1436, books were hand-written and hand-copied which made them very expensive. Only wealthy people could afford books and an education. Although China and Korea had methods of mass production of printed materials before this time, a German man, Johannes Gutenberg, is credited with inventing a modern printing press in Europe. You can see an etching of this press in figure 2.4. The press could make copies of books, pages, and flyers very efficiently. Both the printing presses and the news sheets and books they produced took decades to spread throughout Europe and their colonies. If you are interested in learning more about this revolutionary technology, check out this history blog: Seven Ways the Printing Press Changed the World.

In time, though, literacy itself became a challenge to the complete control of the monarchs and the church. At the time of the invention of the printing press, only 5 percent of Europe’s population could read. By 1700 almost 40 percent of the people could read. Scientists could now share information about their experiments accurately. Ordinary people could share details about what was happening in their town or village, in what could be considered an early version of social media. Regular people, usually White men, could learn for themselves and question the wisdom of their leaders.

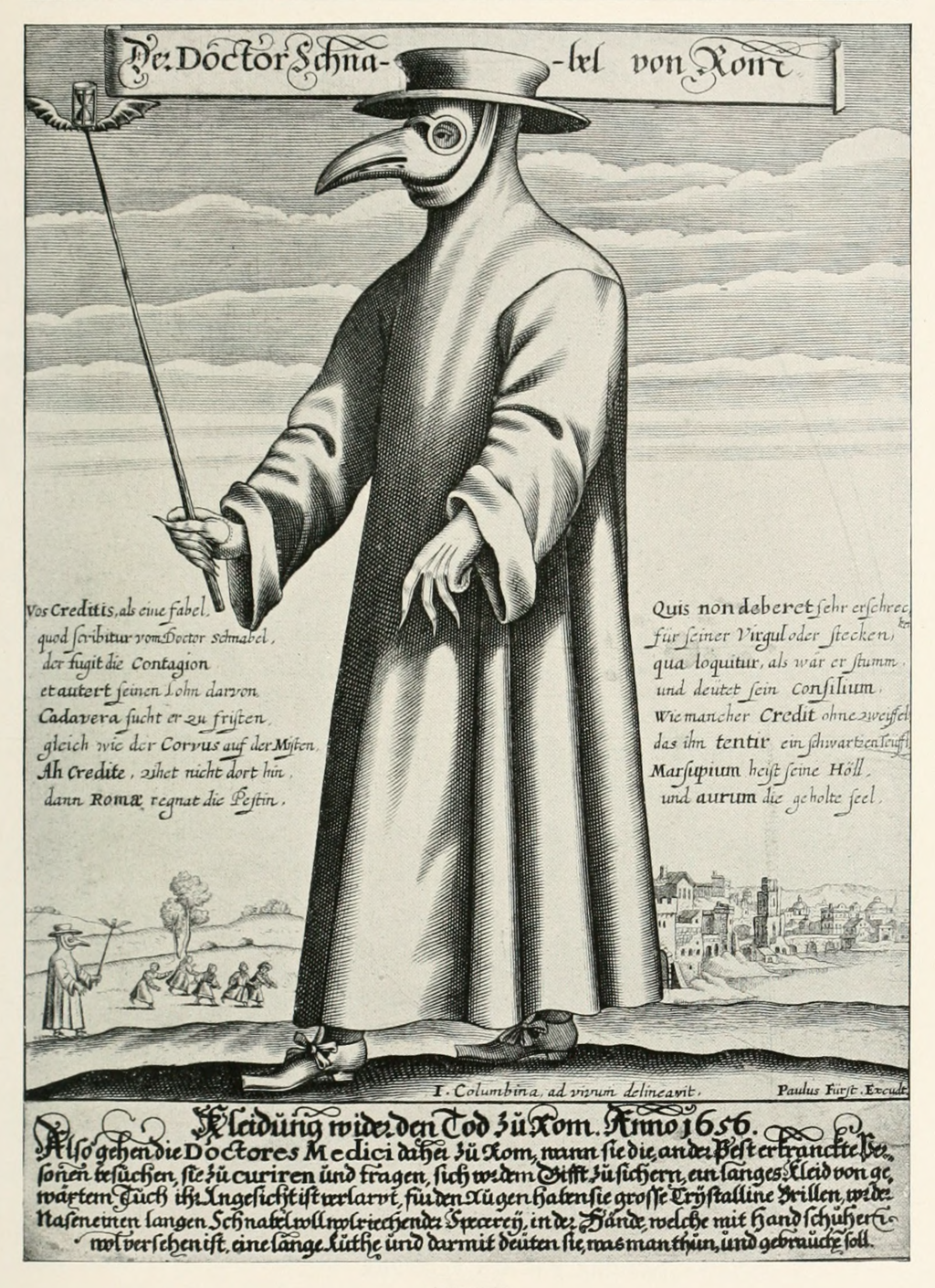

Figure 2.5 The plague doctor: The mask’s beak was filled with herbs to keep out the plague.

A second destabilizing force was the bubonic plague. This plague, also called the Black Death, swept over Europe between 1346 and 1522 CE. The bubonic plague is an infectious disease caused by a specific type of bacteria called Yersinia pestis. This bacterium affects humans and animals and is spread mainly by fleas. Bubonic plague deaths exceeded 25 million people during the fourteenth century—about two-thirds of the population in Europe at the time. You can see an illustration of a plague doctor in figure 2.5. The mask’s beak was filled with herbs to keep out the plague.

Rats traveled on ships and brought fleas and plague with them. Most people who got the plague died, with nodes in the armpit, groin, and neck as large as eggs oozing pus and blackened tissue due to gangrene. A cure for bubonic plague wasn’t available. (This disease still exists today but is now treatable with modern antibiotics.)

The Holy Roman Catholic Church could not explain why this disease was killing people. Health practices were not sufficient to stop the spread of the disease. People started looking for other explanations for disease and deeper understandings of the wider world that exploration and colonization were revealing.

These social forces of catastrophic illness and widespread literacy contributed to the Scientific Revolution (1543–1687). In this period, thought leaders used scientific principles to understand the world around them. They would hypothesize about what was true, observe and measure physical phenomena, and come to conclusions about how the world worked. Many of their theories turned out to be incorrect. However, we still agree that the earth moves around the sun, that disease is spread by contagion, and that gravity is a force in the universe that keeps our feet firmly planted on the ground.

During this period, religious leaders challenged the supremacy of the Holy Roman Catholic Church. The Protestant Reformation can be traced back to 1517 when German theologian Martin Luther posted 95 complaints against the institution of the Catholic Church on a church door in Germany. However, this movement of church reform lasted over 100 years. Spiritual descendants of these reformers ultimately became some of the early American colonists in the 1620s and 1630s.

2.2.3 Thought Revolution (1715–1789)

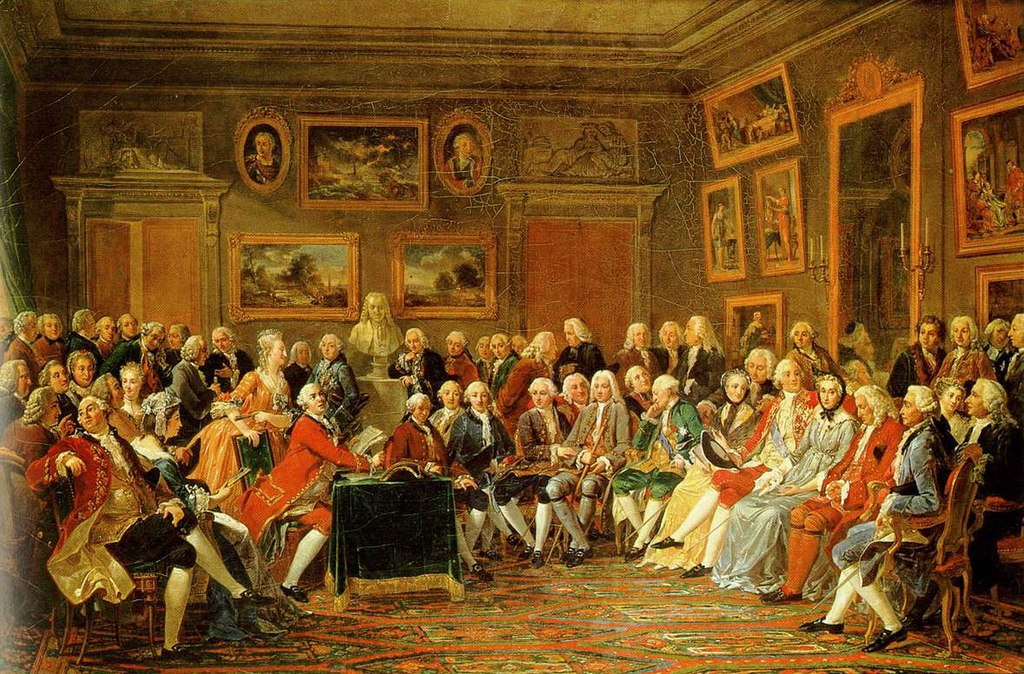

Figure 2.6 Reading in the salon of Marie Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin in 1755, by Anicet Charles Gabriel Lemonnier, c. 1812. Oil on canvas. Château de Malmaison, Rueil-Malmaison, France. Who is missing from this painting?

Together, the Scientific Revolution, the Protestant Reformation, the increase in literacy, the expansion of trade routes, and increased knowledge of the world set the stage for a revolution in thought. This period, often referred to as the Age of Reason or the Enlightenment, provided the philosophical foundations for transformative change (Bristow 2017).

Several of the core beliefs of the Age of Reason contributed to the rise of sociology as a science. Philosophers argued that science and reason could be used to explain the physical and social world. They also asserted that physical and social science could fix the problems of the day. These usually White wealthy men believed that individual people had a right to determine the course of their own lives. Ordinary people could decide what would make them happy. Their ideas about who was a person excluded women, slaves, people who didn’t own land, and Indigenous people. Participation in the discussion of these ideas and in the rights of citizenship was limited at the time, but the ideas encouraged revolution. You might notice, for example, that the painting in figure 2.6 includes mostly White men and only a few women. These philosophers excluded Black, Brown, Indigenous, and other marginalized people.

The philosophers also argued that political leaders and governments only ruled with the consent of the people. The ideas of democracy and individual rights began to create possibilities for revolution. These beliefs were revolutionary because they challenge the idea that God and the King were the source of all truth and all power.

2.2.4 Industrial Revolution (1760–1840)

Figure 2.7a and b Buildings like this old mill in Biddleford, Maine are sprinkled throughout New England. Many of the small towns had mills for wool, shoes, cloth and other materials. This particular set of mill buildings, the Pepperell Mill campus is being repurposed as shops, housing galleries and retail space. What might have it been like to work in one of these mills?

These revolutionary ideas transformed the intellectual discoveries from the scientific revolution into technological and economic revolution. During the 1760s, Scottish engineer James Watt created an effective steam engine. His prototype morphed into the steam-powered locomotive, steam-powered looms for weaving cloth, steamships, and (in an alternate reality) steampunk.

Over the century of the Industrial Revolution, the location of work also changed dramatically. Before the Industrial Revolution, most people in Europe lived and worked on farms. By 1900, over 40 percent of the population of Western Europe lived in cities. The factory-produced goods were carried by train and ship around the world. Although the mass production enabled by the Industrial Revolution made goods like cloth and rugs cheaper, factories often had unsafe working conditions and long hours. Workers, who included men, women, and children, had no way to protest inhumane conditions. These mill buildings exist in large and small towns throughout New England (figure 2.7)

2.2.5 Political Revolution (1775–1821)

Figure 2.8 Haitian Revolution

In addition to revolutionary thought and revolutionary economic transformation, the 1700s and 1800s brought political revolution, as listed in figure 2.9. Ordinary people in European and Asian countries rebelled against centuries-old monarchies. Colonies around the world that had been created in the 1600s began to fight for their own independence. Among the many political revolutions of the time, these four revolutions created countries out of colonies, weakened the power of the monarchy, and began a trend of establishing independence. The figure in 2.8 is a depiction of the Haitian Revolution.

|

Revolution |

Time Period |

Core Dispute |

|

American Revolution |

1775–1783 |

U.S. severs its colonial relationship with England |

|

French Revolution |

1789–1799 |

The French monarchy is abolished |

|

The Haitian Revolution |

1791–1804 |

Toussaint Louverture leads a successful slave rebellion that, establishes Haiti as the first free, Black republic. |

|

The Mexican War of Independence |

1810–1821 |

American-born Spaniards, including the priest and mestizo Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, rebel against Spanish rule. |

Figure 2.9 Chart of Political Revolutions

The video in figure 2.10 is a visualization of how countries and boundaries have changed over time. Please start watching at minute 16, which begins around 16:00. Pay attention to the period of colonization. As you watch you will see the mostly European invasions of other places, and the growth of colonies. The people who lived in these colonies begin to revolt in the late 1700s. Revolutions and dismantling of formal colonialism continues. This long legacy of invasion and control by foreign powers reverberates in the social problems of today.

Figure 2.10 The History of the World: Every Year [YouTube Video]

2.2.6 Sociology Is the Revolutionary Response

Against the background of philosophical, economic, technological, and political revolution, sociology arose as a revolutionary discipline. Practitioners wanted to understand the causes of social upheaval and use this knowledge to solve social problems. Scholars used scientific principles to understand what was true about our social world, coming up with ideas about how things worked and proposing solutions to societal breakdowns and social problems. Although the findings of early sociologists were sometimes racist, sexist, homophobic, and ableist, the application of science to solve human problems was remarkable. Each of the following founders of sociology studied a particular set of social problems. If you click on each name, you can find out more about each person and the contributions they made to the emerging discipline of sociology.

Figure 2.11 The title page of Emile Durkheim’s book on suicide

French Jewish sociologist Emile Durkheim studied the social problem of suicide. At that time, the Holy Roman Catholic Church described suicide as a mortal sin against God and the church. People who committed suicide were not allowed to be buried on church grounds. Durkheim proposed several reasons that people decide to commit suicide. He asserted that people commit suicide because connections in their society are breaking down. A person might also commit suicide because their society was too restrictive (figure 2.11).

English social theorist Harriet Martineau studied the social problems of poverty and slavery. Unusually for the time, she was an educated woman. Because she was both White and wealthy she was able to study and research. She traveled to the American south and interviewed people to understand more about gaps between American ideals of freedom and liberty, and the lived reality of slavery. She also examined women’s roles, women’s rights, and family life as a field of sociological study.

German philosophers Karl Marx and Fredrick Engles studied the social problems of revolution and industrialization. They proposed that revolution was an inevitable outcome of the unequal distribution of wealth between the rich, who owned land and factories, and the poor, who didn’t. Marx and Engles, both wealthy German men, were revolutionary thinkers because they followed the money—who had it and who didn’t—to explain conflict in society.

German sociologist Max Weber studied the social problems of capitalism and bureaucracy. He agreed with Marx about the importance of the economic inequality driving social disruption. However, he argued economics alone was insufficient to explain revolution. He added the idea that people’s beliefs and values contributed to the choices that they made. Most specifically, he said that the value of hard work in Protestantism contributed to the spread of capitalism.

All of these sociologists were taking a revolutionary approach, applying science to understand the problems of their times. Each of them proposed a reason based in logic and science to explain the social problems of their time. In a world that was faced with environmental, economic, and political unrest, these thinkers were revolutionary because they investigated causes and proposed solutions to the suffering of their time.

Let’s now look more about what makes sociology a social science: social theory and research methods. The following sections explore core sociological theories and the methods by which sociologists actually do science.

2.2.7 Licenses and Attributions for Sociology as a Revolutionary Response

“Sociology as a Revolutionary Response” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.2 Sociology as a Revolutionary Response by Micaela Willi Hooper and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.3 Painting of Christopher Columbus on Santa Maria in 1492 by Emanuel Leutze, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons public domain.

Figure 2.4 Early Press, etching from early Typography by William Skeen 1872, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons public domain.

Figure 2.5 The Plague Doctor Costume by I. Columbina, ad vivum delineavit, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons public domain.

Figure 2.6 Painting In the Salon of Madam Geofrin by Anicet Charles Gabriel Lemonnier, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons public domain.

Figure 2.7a Pepperell Mill Complex Mill building in Biddleford, ME. by Markus Jansen licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.7b Pepperell Mill Complex Mill building in Biddleford, ME. by Valerie McDowell licensed under CC BY 4.0.[a]

Figure 2.8 Hatian Revolution by Karl Girardet and Jean Outhwaite, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons public domain.

Figure 2.9 Chart of Political Revolutions by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.10: “The History of the World Every Year” by Drex and Ollie Bye. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 2.11 Front Cover of Le Suicide by Internet Archive, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons public domain.