2.3 What is Social Theory?

Sociologists and other scholarly thinkers use theories to help them understand the social world and how it works. Theories are sets of ideas that explain something. More specifically, a theory is a statement that proposes to describe and explain why facts or other social phenomena are related to each other based on observed patterns. For example, Gloria Anzaldúa and Patricia Hill Collins are well-known scholars who created theories that explain racial, ethnic, and gender oppression (figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12 Gloria Anzaldúa (on left) and Patricia Hill Collins (on right) are highly influential theorists in the areas of feminist theory and racial and ethnic studies.

In this section, we discuss historical and contemporary theories and theorists that assist us in thinking deeply about the causes and consequences of social problems, such as racism, poverty, and discrimination based on sexuality and/or gender. Using social theory helps us to get a better understanding of why and how social problems exist. This understanding, in turn, can help us better prevent and address social problems.

2.3.1 What Is a Theory?

Social theory helps us put into words the underlying mechanisms that guide society and our social interactions (Lemert 1999). By analyzing society in this way we can better understand the causes and consequences of social problems. For example, Karl Marx’s theory of capitalism helps us understand working poverty by outlining the ways profit is generated through worker exploitation. According to Marx ([1867] 2012), the worker is not paid the full value of their labor. The business owner, or bourgeoisie, takes a percentage of the value created by the worker and keeps it as profit. The bourgeoisie is always looking for ways to decrease worker wages and increase profit, which results in low-wage work and working poverty. By analyzing and critiquing capitalism, Marx explained a hidden part of everyday experience. In this way, theory can be liberating because it allows us to better understand the workings of the social world in which we live.

2.3.2 Macro and Micro Level Theories

Theories can be categorized, as either macro or micro, based on the size of the phenomenon they seek to explain. A macro-level theory (such as Marx and Engels’s critique of capitalism) examines larger social systems and structures, such as the capitalist economy, bureaucracies, and religion. A micro-level theory examines the social world in finer detail by discussing social interactions and the understandings individuals make of the social world.

A good example of micro-level theory comes from Canadian-American sociologist Erving Goffman, who studied one-on-one social interactions and the meanings that emerged from them. Goffman (1963) is famous for having created a theory about stigma, the social process whereby individuals that are taken to be different in some way are rejected by the greater society in which they live based on that difference. He explains that stigma is generated when a person possesses an attribute that makes them different and may cause them to be perceived as bad, dangerous, or weak.

Goffman (1963) writes that the person possessing this attribute of stigma “is thus reduced in our minds from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one” (p. 3). The possession of stigma can introduce tension into everyday social interactions (Bell 2000). Stigma plays the role of a mark that links its bearer to undesirable characteristics, which in turn cause the stigmatized person to experience rejection and isolation (Link et al. 1997). As we will discuss more in Chapter 9, having a diagnosis of mental illness often carries stigma.

Micro-level theory has a long history within sociology. One of the most common micro-level approaches is symbolic interactionism, a sociological approach that focuses on the study of one-on-one social interactions and the meanings that emerge from them. Goffman’s theories have roots in social theory created in the early twentieth century by George Herbert Mead, an American philosopher who described how social processes created one’s understanding of themself, or their social self. According to Mead (1934), the self is not a biological body or an inherent personal quality, but rather the self is an image of oneself generated entirely from experiences in the social world. The social insights offered by Goffman, Mead, and other symbolic-interactionists help us understand how situations come to be defined as “social problems” through the meanings made in social interactions between people. As we know, situations are not automatically defined or understood as problems; we attach meanings and labels to situations that make them social problems.

Many sociology textbooks organize their material around three theoretical frameworks: structural functionalism (often shortened to functionalism), conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism (often shortened to interactionism). These frameworks tend to correspond to theories created by prominent White male scholars of the nineteenth century. Because they are used so regularly within our field, we have offered a summary of each approach in figure 2.13.

While these approaches are useful, the categorization hides the explanatory power of multiple approaches. Feminist, intersectional, decolonial, anti-racist, and other theoretical perspectives provide multifaceted ways of interpreting our social world. Discussions of alternatives to these core theories starts in the next section.

|

Theoretical perspective |

Major assumptions |

Views of social problems |

|

Functionalism |

Social stability is necessary for a strong society, and adequate socialization and social integration are necessary for social stability. Society’s social institutions perform important functions to help ensure social stability. Slow social change is desirable, but rapid social change threatens social order. |

Social problems weaken a society’s stability but do not reflect fundamental faults in how the society is structured. Solutions to social problems should take the form of gradual social reform rather than sudden and far-reaching change. Despite their negative effects, social problems often also serve important functions for society. |

|

Conflict theory |

Society is characterized by pervasive inequality based on social class, race, gender, and other factors. Far-reaching social change is needed to reduce or eliminate social inequality and to create an egalitarian society. |

Social problems arise from fundamental faults in the structure of a society and both reflect and reinforce inequalities based on social class, race, gender, and other dimensions. Successful solutions to social problems must involve far-reaching change in the structure of society. |

|

Symbolic interactionism |

People construct their roles as they interact; they do not merely learn the roles that society has set out for them. As this interaction occurs, individuals negotiate their definitions of the situations in which they find themselves and socially construct the reality of these situations. In so doing, they rely heavily on symbols such as words and gestures to reach a shared understanding of their interaction. |

Social problems arise from the interaction of individuals. People who engage in socially problematic behaviors often learn these behaviors from other people. Individuals also learn their perceptions of social problems from other people. |

Figure 2.13. Three theoretical sociological perspectives: functionalism, conflict theory, symbolic interactionism

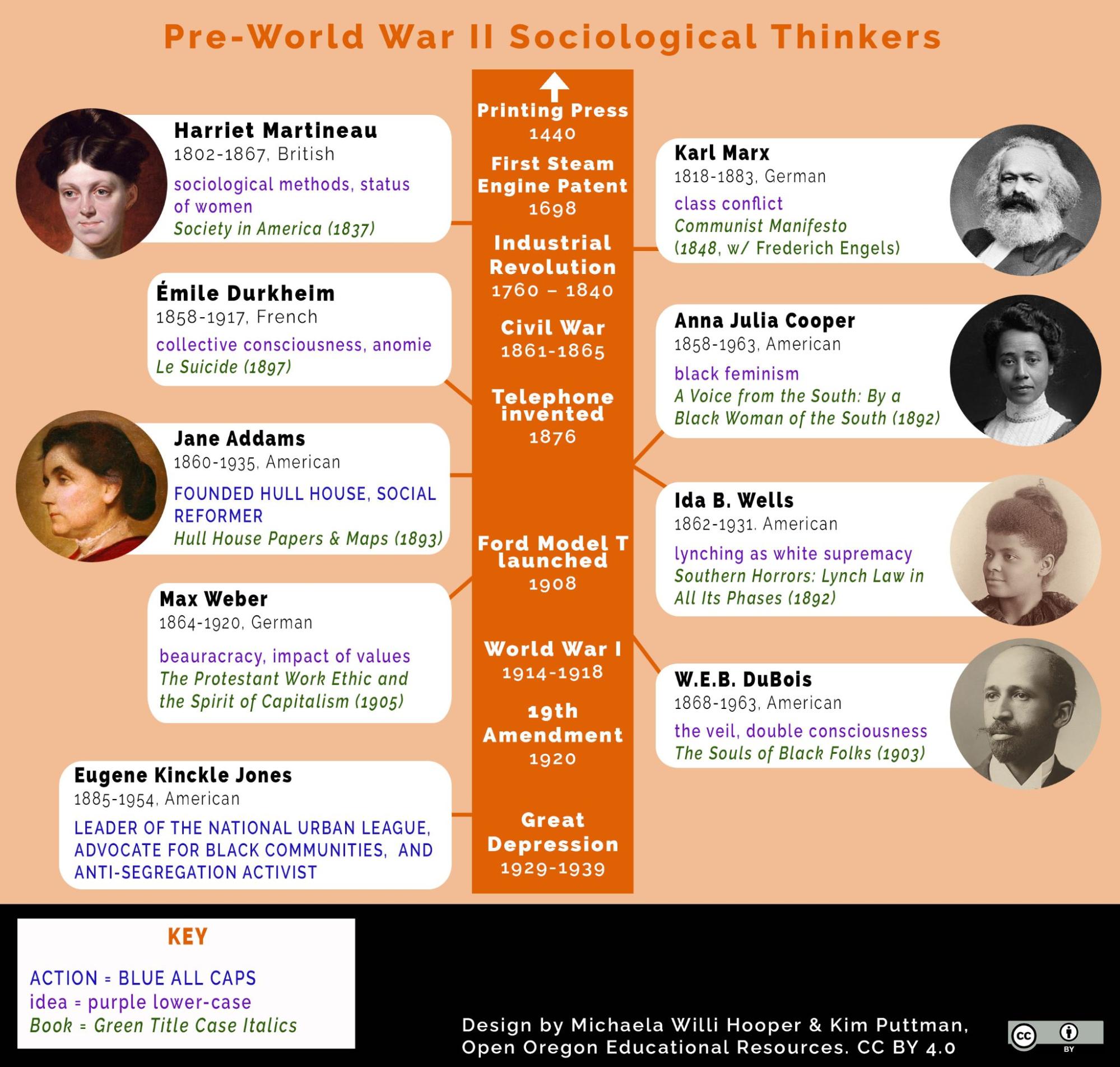

Each of these theorists was responding to social concerns of the time in which they lived, whether they were experiencing social upheaval, war, economic depression or economic stability. As we can see from figure 2.14. Marx, Durkheim and Weber were responding to social forces related to the industrial revolution. Martineau, Cooper, and Wells examined changes in womens’s roles related to the industrial revolution, and the American Civil War. Dubois explored the experiences of black people during and after slavery. Addams created services for immigrants before and after WWI. Irwati Karve looked at kinship in India, from an Indian perspective, rather than a British one. Eugene Kinkle Jones created social opportunities for Black people after the Civil War, and beyond.

2.14 Key Sociological Thinkers – Industrial Revolution to WWII. Figure 2.14 Image Description

2.3.3 The Beginnings of Critical Race Theory

Though many of the most recognized classical theorists of sociology came from European White cultural backgrounds during the nineteenth century, plenty of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color were creating social theory and adding to our understanding of social problems. Their voices weren’t often recognized or heard as fully as the so-called founding fathers of sociology, Karl Marx, Max Weber, and Emile Durkheim.

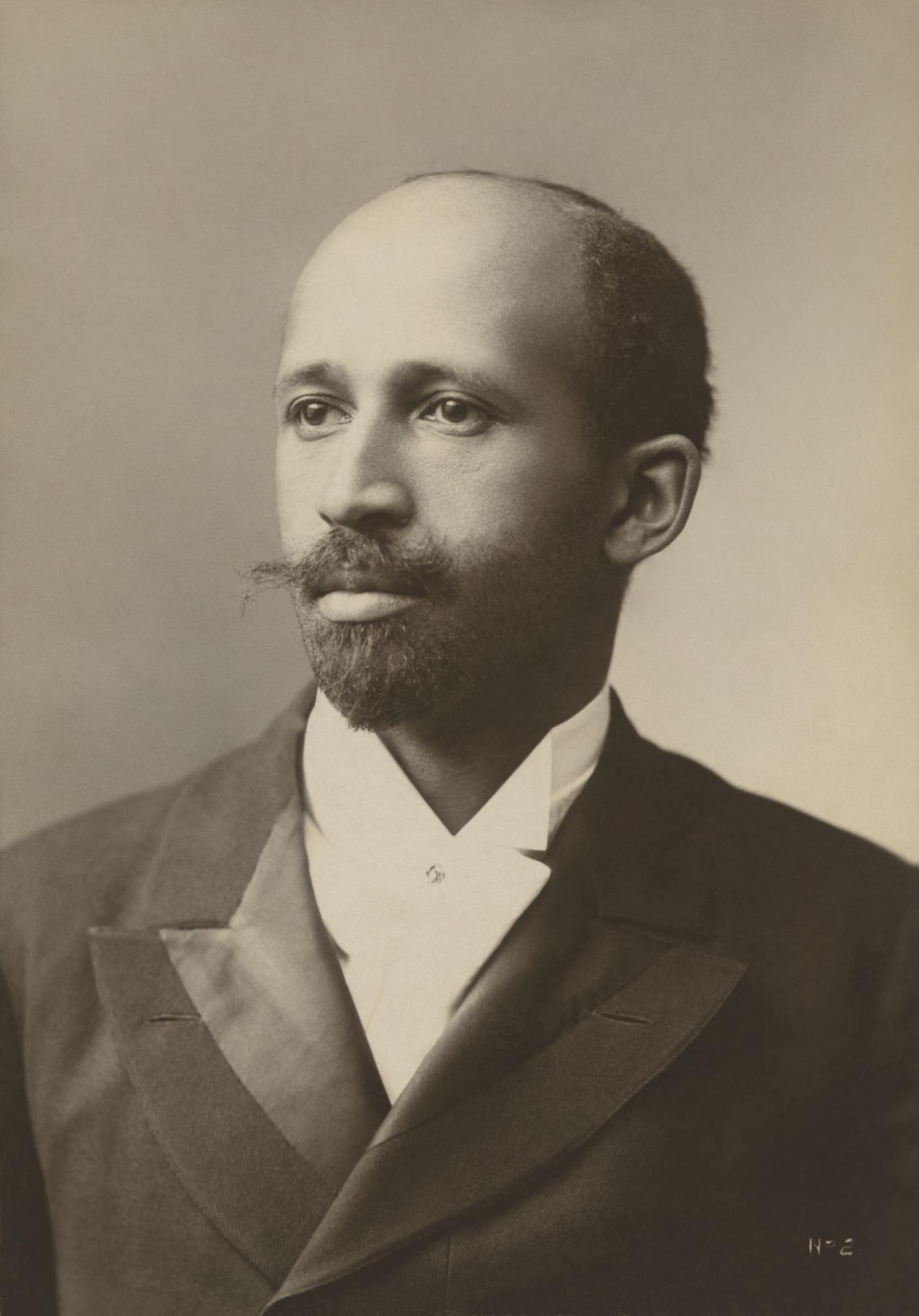

Figure 2.15 W. E. B Du Bois

W. E. B. Du Bois was one of the first sociologists to publish scholarly work that discussed race and racism. In this way, he provided a critical intervention into sociological theory and his writings critiqued the absence of racial analysis from previous social theory. Du Bois was the first Black American to earn a PhD at Harvard, which he did in 1895. He studied economics, history, sociology, and political theory.

One of Du Bois’s most influential contributions to sociological theory came from his discussion of the veil and double consciousness. He writes that the Black American is “born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world” (1903:3). He points out that Black Americans have a double consciousness because they also see themselves through the eyes of White America.

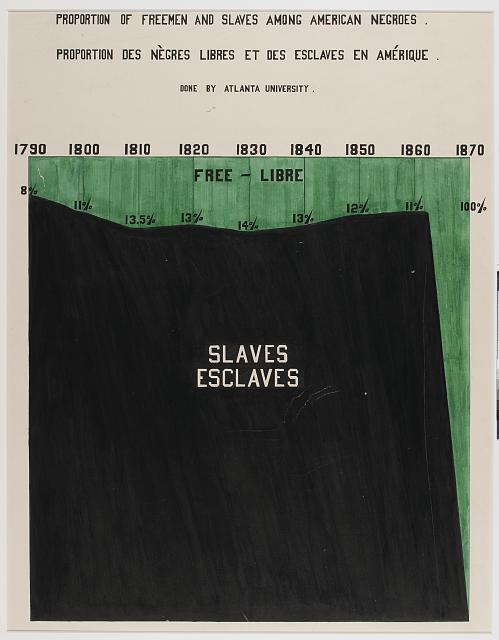

Figure 2.16 Infographic; Du Bois’s Proportion of freedmen and slaves among American Negros.

Du Bois established the first school of American sociology at Atlanta University. With his team, he also created some of the first data visualizations in American sociology to illustrate the conditions of life for Black Americans. The infographic in figure 2.16 shows the percent of Black slaves and freemen between 1790 and 1870, when slavery was declared illegal. These studies and infographics were part of his groundbreaking sociological analysis of poverty among Black Americans. His words are still quoted today among advocates of racial justice.

Du Bois analysis continues to inform our experiences and conversations around race even today. CNN recorded interviews with Black people and shared them on Twitter. If this experience of race consciousness is new to you, please watch, “The Moment I Realized I Was Black.”

2.3.4 Feminism and Intersectionality

Despite the variations between different types of feminist approach, there are four characteristics that are common to the feminist perspective:

- Gender is a central focus or subject matter of the perspective.

- Gender relations are viewed as a problem: the site of social inequities, strains, and contradictions.

- Gender relations are sociological and historical in nature and subject to change and progress.

- Feminism is about an emancipatory commitment to change: the conditions of life that are oppressive for women need to be transformed.

One of the sociological insights that emerged with the feminist perspective in sociology is that “the personal is political.” Many of the most immediate and fundamental experiences of social life—from childbirth to who washes the dishes to the experience of sexual violence—had simply been invisible or regarded as unimportant politically or socially.

White British born Canadian sociologist Dorothy Smith’s development of standpoint theory was a key innovation in sociology that enabled women’s experiences and issues to be seen and addressed in a systematic way (Smith 1977). Scientists of the time argued that science was logical and objective. Smith, on the other hand, argued that where you stand, or your point of view, influences what you notice. Women and other marginalized people could see systems of oppression more clearly because they experienced them. She recognized from the consciousness-raising groups initiated by feminists in the 1960s and 1970s that many of the immediate concerns expressed by women about their personal lives were ignored by academics, politicians, and lawers.

Part of the issue was sociology itself. Smith argued that instead of beginning sociological analysis from the abstract point of view of institutions or systems, women’s lives could be more effectively examined if one began from the “actualities” of their lived experience in the immediate local settings of “everyday/everynight” life. She asked, “What are the common features of women’s everyday lives?”

From this standpoint, Smith observed that women’s position in modern society is acutely divided by the experience of dual consciousness. One consciousness was centered in family. Then they had to cross a dividing line as they went out in the world, dealing with work or the institutions of schools, hospitals and governments. Women had to use a second consciousness to navigate this. These institutions didn’t see women’s real and personal understandings of the world. (Smith 1977).

The standpoint of women is grounded in relationships between people, because they have to care for families. Society however, is organized through “relations of ruling,” which translate the substance of actual lived experiences into rules and laws. Power and rule in society, especially the power and rule that limit and shape the lives of women, operate as if there is one objective reality, rather than differences in people’s lived experiences. Smith argued that the abstract concepts of sociology, at least in the way that it was taught at the time, only contributed to the problem. This theory, while it seems obvious now, was revolutionary at the time. And, though groundbreaking, it had its limits.

The feminist perspective within social theory has changed throughout the years. From the 1800s until the mid-twentieth century, the central focus or subject matter was differences between women and men. Race and class were generally ignored. Black feminists pointed out that previous forms of feminist theory were mostly concerned with the issues of White middle-class and wealthy women. This was a critical intervention into the perspective of feminist theory.

Early Black feminist theorists built the foundation for the study of feminist intersectionality. Intersectionality, as you read in Chapter 1, is a perspective and a theory that analyzes and interrogates the ways race, class, gender, sexuality, and other social structures of privilege and oppression overlap and work together.

Though the concept of intersectionality emerged from a critique of White feminist theory and activism that ignored the experiences of Black and Indigenous women of color, its roots can be found in the work of Anna Julia Cooper (1858–1964) and Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862–1931). In their own ways Cooper and Wells-Barnett brought a sociological consciousness to their response to the Black experience and focused on the toxic interaction between difference and power in U.S. society (Madoo and Niebrugge 1998).

Looking at society through the lenses of race, gender, and class, Cooper and Wells-Barnett, though they worked separately, both created a Black feminist sociology. They both pointed out that “domination rests on emotion, a desire for absolute control” (Madoo and Niebrugge 1998:169). Their point was that societal domination is not just about making a profit or otherwise increasing one’s financial status. Rather, there is an emotional factor within societal domination. Cooper (1892) provides an example by noting the extra expense paid by railroad companies of providing a separate car for people of color, as discussed in the beginning of the chapter.

Though Wells-Barnett was a journalist, she made contributions to sociological thought by way of her activism against lynching. She researched and published accounts of lynching that showed the out of control aggression of White Americans towards Blacks (Madoo and Niebrugge 1998). After examining the various excuses used by Southern Whites for their attacks on Blacks, Wells-Barnett ([1895] 2018) wrote that there would be no need for her research, “If the Southern people in defense of their lawlessness, would tell the truth and admit that colored men and women are lynched for almost any offense, from murder to a misdemeanor” (p. 11).

These Black feminist founders of sociological thought planted the seeds for the emergence of influential sociological theory from the 1980s and 1990s, which centered on the experiences of Black and Indigenous women of color. Though the concept of intersectionality is most often attributed to critical race legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, within sociology Patricia Hill Collins (1948–present) is recognized for providing complex and detailed analyses of the concept. Her theorization of the outsider within perspective shows how Black women “have a clearer view of oppression than other groups” whose identities are different (1986:20). Collins (1986) details how Black women participate in social systems but not as insiders, given their oppression. Participating in a social system that oppresses them, Black women have a privileged standpoint that offers more information. They can see more clearly how our social structures of race and gender work intersectionally.

Collins’s (1986) theory of interlocking oppressions points out philosophical foundations that underlie multiple systems of oppression. It is common in sociology to explain inequality in terms of race, class, or gender alone. Either you are Black or White, male or female, young or old, and so on. One group in each dichotomy has more power than the other. With some additional complexity, sociologists discuss issues of oppression related to race and class or age and gender, for example. Collins argues that these either/or additive approaches missed the point.

Instead, Collins explains that oppression exists as a matrix of domination in which society’s multiple interlocking levels of domination stem from the social construction of race, class, and gender. Patriarchy and ableism work together to make disabled women and nonbinary people invisible. Systemic racism, homophobia, and classism interlock to oppress poor trans people of color. This Black feminist analysis sees the holistic experience of interlocking and simultaneous oppressions and challenges people to see wholeness instead of difference (Collins 1986).

These same oppositional differences are seen in the work of Chicana theorist and activist Gloria Anzaldúa (1942–2004). Anzaldúa theorizes the idea of the borderlands, or la frontera. The borderlands is a terrain, both literal and imagined, where we live. Living in the borderlands involves the simultaneous occurrence of contradictions. Anzaldua (1987) writes that when you live in the borderlands you are a “forerunner of a new race, half-and-half—both woman and man—neither—a new gender (p. 216). She uses various writing styles including poetry, as well as various languages to write her theory. In this way she challenges the usual, or dominant, way of composing scholarship. Her transitions between languages and dialects were groundbreaking and served to question the dominance of certain languages (English) and ways of speaking (“proper” English).

Together these Black and Indigenous theorists of color advanced scholarly understandings of difference and oppression. Many of them also used nontraditional methods to articulate their ideas, often using personal experience or placing value on emotion. This contrasts with historical ways of doing theory that emphasized objectivity and reason. Objectivity refers to the idea of conducting research with no interference by aspects of the researcher’s identity or personal beliefs. Contemporary scholars believe it is impossible to ever be completely objective. Another similarity between these theorists is the links they made between composing scholarly work and doing activism out in the world. They worked to bridge the two and to advocate for a reciprocal relationship, so that what was happening out in the world was directly impacting scholarly work.

2.3.5 Critical Race Studies

To better understand race and racism, social scientists examine racial power dynamics in the United States and throughout the world. Sociologists have long understood race to be a social construct, meaning that it is a product of social thought rather than a material or biological reality. Yes, people have different levels of melanin in their bodies, but that is as far as any biological notion of race goes. One sociological theory of race describes how race is an on-going, ever-evolving construction with historical and cultural roots (Omi and Winant 1986). The long-lasting economic inequality caused by slavery and systemic racism combines with all of the racial stereotypes circulating in media and popular thought to create our current racial formation.

Racial formation refers to the categories of race that we currently have in this country and all of the meanings popularly attached to them. The racial formation in the United States will look different than in other countries. For example, Brazil has a different set of racial categories and a different way of racially categorizing people. The United States itself has counted race differently in different decades. In 1790, the census counted free White women and men, other free people, and slaves. In 2010, the categories were expanded to include White, Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Other, and Hispanic. By 2020, though the categories themselves didn’t change much, people could select more than two options. These census changes help us to more accurately reflect our multiracial and diverse population (Marks and Rios-Vargas 2020).

While understanding the socially constructed nature of race is important, American social theorist Joe R. Feagin (2006) criticizes racial formation theory for failing to include an understanding of how slavery generated huge profits for White Americans who then passed that money on to their future generations. Feagin’s view of systemic racism insists on understanding the long-lasting impacts of slavery, as well as recognizing White-on-Black oppression as firmly embedded within U.S. society. Feagin (2006) writes, “For a long period now, white oppression of Americans of color has been systemic—that is, it has been manifested in all major societal institutions” (p. xiii).

Another set of theories on race, called critical race theory (CRT), have garnered attention in the media lately, becoming a contentious topic for school boards and parents. Critical race theory emerged in the 1980s out of a concern by legal scholars of color that the measures installed by the civil rights movement to alleviate racial injustice were no longer addressing the problem, or never did.

Critical race theorists take a systemic view of racism. They see racism not as a quirk within our society, but as an everyday occurrence within many, if not all, parts of life (Delgado and Stefancic 2017). Focusing on the legal sphere, they raise questions about the law’s ability to address systemic racial inequality.

The current discussion around critical race theory involves worries by some that it is being taught in public K-12 schools. Some people are concerned that White children are being made to feel guilty for being White. Those with knowledge of critical race theory point out that it is most often taught in law school and would be far too advanced to be found in the K-12 curriculum. Advocates for racial justice affirm the importance of discussing race and racism with children in school settings. If you would like to learn more, check out this blog “Critical Race Theory: ‘Diversity’ Is Not the Solution, Dismantling White Supremacy Is.”

2.3.6 Queer Theory

Queer theory is an interdisciplinary approach to sexuality and gender studies that identifies Western society’s rigid splitting of gender into male and female roles and questions the manner in which we have been taught to think about sexual orientation and gender. By calling their discipline queer, scholars reject the effects of labeling; instead, they embraced the word queer and reclaimed it for their own purposes. The perspective highlights the need for more flexible and fluid notions of sexuality and gender that allow for change, negotiation, and freedom. One concrete example would be allowing individuals to write in their gender identity on forms or leave it blank.

French social theorist Michel Foucault (1978) traced the history of the concept of sexuality and saw that powerful forces encouraged its development as part of an effort to reveal and eliminate any deviant forms of sexual expression. Foucault’s work on sexuality raises many questions: Why are we asked to identify as a specific sexuality? Wouldn’t we be freer if sexuality wasn’t categorized (e.g., homosexual/ heterosexual)? Of course, many LGBTQIA+ activists would argue otherwise, given the power in self-identification and advocacy for rights and respect.

Another well-known queer theorist, Judith Butler, also critiqued categorizations, but her objections included gender identities. As with Foucault, she felt these categories were limiting. Butler is recognized among sociologists for developing the theory of the performativity of gender. This theory describes gender as a way of appearing to others, through clothing, nonverbal communication, make-up, etc., instead of an inner feeling or identity. Thus, gender is a matter of learned performance and can be reconstructed (Willchins 2004). This theory opens the doors for us to re-think what we want gender to mean, or for us to do away with the concept of gender altogether and replace it with something else. Theorists who use queer theory strive to question the ways society perceives and experiences sex, gender, and sexuality, creating a new scholarly understanding.

These contemporary sociologists are also responding to core events in their times. The infographic in figure 2.16 locates contemporary theorists related to critical social and economic events. As you review this detail, consider how your perspective might change if you were trying to explain the Vietnam War, or provide theories that would explain the Civil Rights Movement.

Figure 2.17 Modern Sociologists. Figure 2.17 Image Description

2.3.7 Theories of Interdependence and Complex Systems

As we discussed in Chapter 1, we are interdependent. We need each other to survive and thrive. How do sociologists understand this concept and apply it to understand the social world?

To answer that question, we need to start with our friends, the biologists. Like Simba and the pride in the circle of life as described in The Lion King, biologists recognize that all of life is interconnected. They call specific instances of this interdependence, ecosystems. An ecosystem is a geographic area where plants, animals, and other organisms, as well as weather and landscapes, work together to form a bubble of life.

Figure 2.18 Sea Stars and Sea Anemones at Haystack Rock, Oregon. There’s no water so the anemones are closed. Each creature depends on the healthy ecosystem.

A tide pool is a tiny ecosystem, like the one shown in figure 2.18. The pool contains seaweed which photosynthesizes and creates oxygen and plant matter. Tiny abalone eat the seaweed. Mussels cling to the rocks filtering the ocean water and eating the small life the water contains. Sea anemones eat plankton and small fish. Sea stars eat the clams and mussels. The whole ecosystem depends on the moon and the tides to be refreshed and restored. If you remove one part, the tiny ecosystem of the tide pool falls apart.

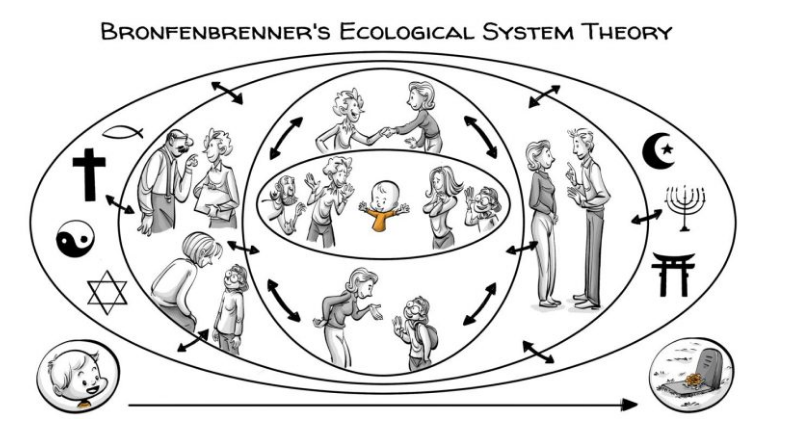

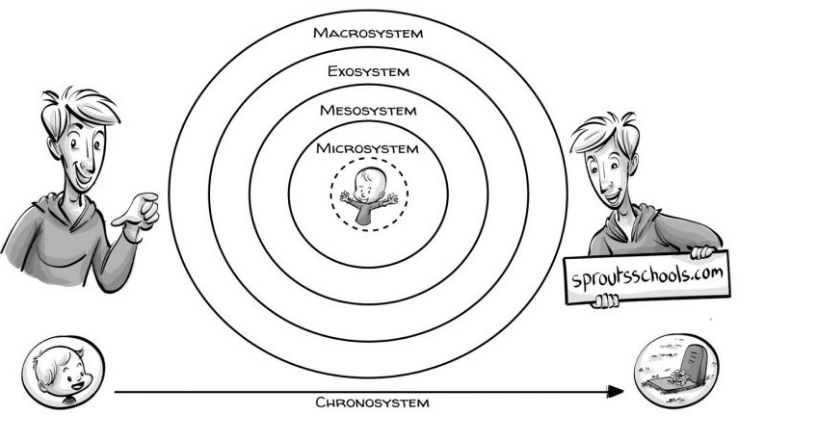

In the mid-1950s social scientists began to apply this idea to human systems also. Russian-born American Psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner proposed the ecological systems model to describe the social influences on individual life. The common understanding of poverty at that time was that people were poor because they made bad choices. Bronfenbrenner’s model suggested that there were outside influences which contributed to poverty beyond the level of the individual. This sounds a lot like the sociological imagination from Chapter 1, doesn’t it? The following two diagrams and the associated video illustrate the concept (figure 2.19 Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory, and figure 2.20 Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory with labels).

Figure 2.19 Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory

Figure 2.20 Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory with labels

In the ecological system theory model, the social world contains layers, each with its own influence on a child. The system moves from the smallest level of the individual child to the microsystem of family, through growing layers until it reaches the macrosystem of institutions and society. The systems also change over the lifetime of the person, as represented by the chronosystem.

This early model of applying ecosystems to human behavior was very effective. As a result of presenting this model to the U.S. Congress, Head Start was created. This program provides free preschool to young children in high-poverty areas. For a more complete story, feel free to watch “Ecological System Theory [YouTube Video].”

Sociologists have built on the social ecosystem model proposed by psychologists. An online search of wide-ranging topics from the root causes of health inequality, increasing economic equity for young Black men or addressing bullying of LGBTQIA+ students will turn up variations of this model.

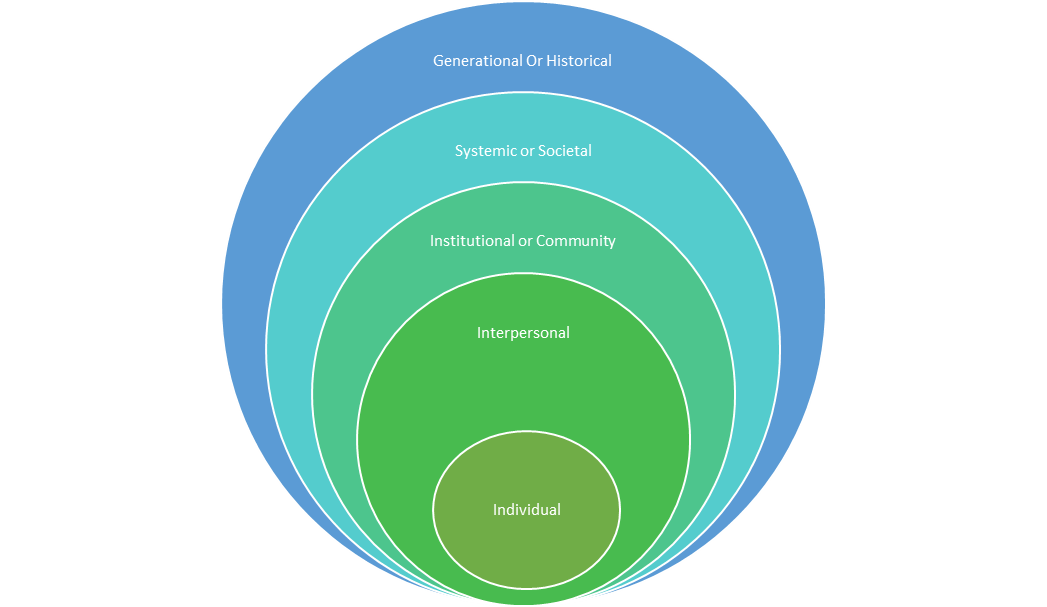

The labels of all of the circles vary, depending on the problem researchers and activists are trying to describe. However, all of the social ecology models move from the personal and individual out through the layers to systemic or structural causes of social problems.

The model in figure 2.21 is useful in understanding the various levels of society by showing how individual, community and institutional actions are connected. Seeing these levels clearly also helps us see the harm that can happen at each level as well as the healing that is possible. This model, and the table in figure 2.22 that describes it, will be used throughout the book to anchor our discussions where social problems occur in society. The social ecological systems model also helps us link individual agency and collective action as we work to solve interdependent social problems.

Figure 2.21: Social ecosystem model, also known as social structure

The table in figure 2.21 provides more detail about each level. Don’t worry if you don’t capture every detail. You will see this illustration often, so you have time to make sense of it.

|

Level |

Description |

Harm |

Healing |

|

Individual |

This level reflects the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of an individual. |

Prejudice, internalized homophobia, or implicit bias may cause harm. |

Recognizing unconscious assumptions or internalized hatred may allow healing. |

|

Interpersonal |

This level reflects interactions between people, in families and in groups. |

Microaggressions, name calling, and violence against individuals or groups may cause harm. |

Practicing anti-racist behaviors or stepping forward/stepping back to center the experiences of marginalized people may allow healing. |

|

Community/Institutions |

This level reflects institutions like school, work, church, or government. It can also reflect your neighborhood, city, or state. |

Laws, policies, or implementation of those policies may cause harm. |

Changes in laws, policies or practices may allow healing. |

|

Systemic or Societal |

This level reflects structures or culture that surround the institutions. |

A hierarchy of groups or pervasive beliefs, attitudes, or actions that one group is superior to another may cause harm. |

Focusing on institutionalizing equitable practices and promoting cultural change at all levels of society may allow healing. |

|

Generational or Historical |

This level reflects time – the past structures of society or behaviors that are passed from parents to children. |

Trauma, oppression, and violence of the past may have caused harm. |

Recognizing the historical roots of oppression and repairing the harm, or healing intergenerational trauma may allow healing. |

Figure 2.22 Social ecology and structure: explanatory table

Each of these theoretical approaches explains society with a different lens. Depending on the questions you are asking, one lens may be more useful than another. Similarly, social scientists use different techniques to explore the answers to their questions. In the following sections, we explore these methods, and the ethics related to their use.

2.3.7 Licenses and Attributions for What Is Social Theory?

“What is Social Theory?” by Kelly Stolz and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.12 Gloria Anzaldua

Attribution: K. Kendall, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons; Patricia Hill Collins

Figure 2.12a Gloria Anzaldúa by K. Kendall. License: CC BY 2.0.

Figure 2.12b Patricia Hill Collins by Valter Campanato/Agência Brasil. License: CC BY 3.0 BR.

Figure 2.13. “Social Problems: Continuity and Change[b]” (table) by University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing Licence: CC BY-NC-SA

2.14 Key Sociological Thinkers – Industrial Revolution to WWII by Michaela Willi Hooper, and Kimberly Puttman, Open Oregon Educational Resources. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.15 W.E.B Du Bois by James E. Purdy, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Public Domain.

Figure 2.16 Proportion of freemen and slaves among American Negroes by Atlanta University students, via the Library of Congress is in the Public Domain.

2.3.5 Feminist/Intersectionality is adapted from “Reading: Feminist Theory” by Course Hero, Alamo Sociology is under multiple Creative Commons licenses. Modifications: edited to simplify reading level.

Figure 2.17 Key Sociological Thinkers – Contemporary by Michaela Willi Hooper, and Kimberly Puttman, Open Oregon Educational Resources. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.18Photo by USFWS – Pacific Region. Licence: CC BY NC 2.0

Figure 2.19 Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory by Jonas Koblin. Licence: CC BY NC.

Figure 2.20 Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory with labels by Jonas Koblin. Licence: CC BY NC.

Figure 2.21 and 2.22: Social Ecosystem Model Diagram and table by Kimberly Puttman. Licence: CC BY 4.0.