3.4 Education, Poverty, and Wealth

In the previous sections, we’ve looked at how education is a social problem. As we examine who gets educated, we see inequality. When we look at the outcomes of education, we see achievement gaps and significant education debt. Your social location plays a significant role in your school experience.

Further, we see that actions at all levels of society impact our shared access and outcomes. Schools, neighborhoods, states, the federal government, and concerned parents and citizens take action to create or prevent change. Our choices in this interdependent system contribute to creating more or less equity for the people who learn.

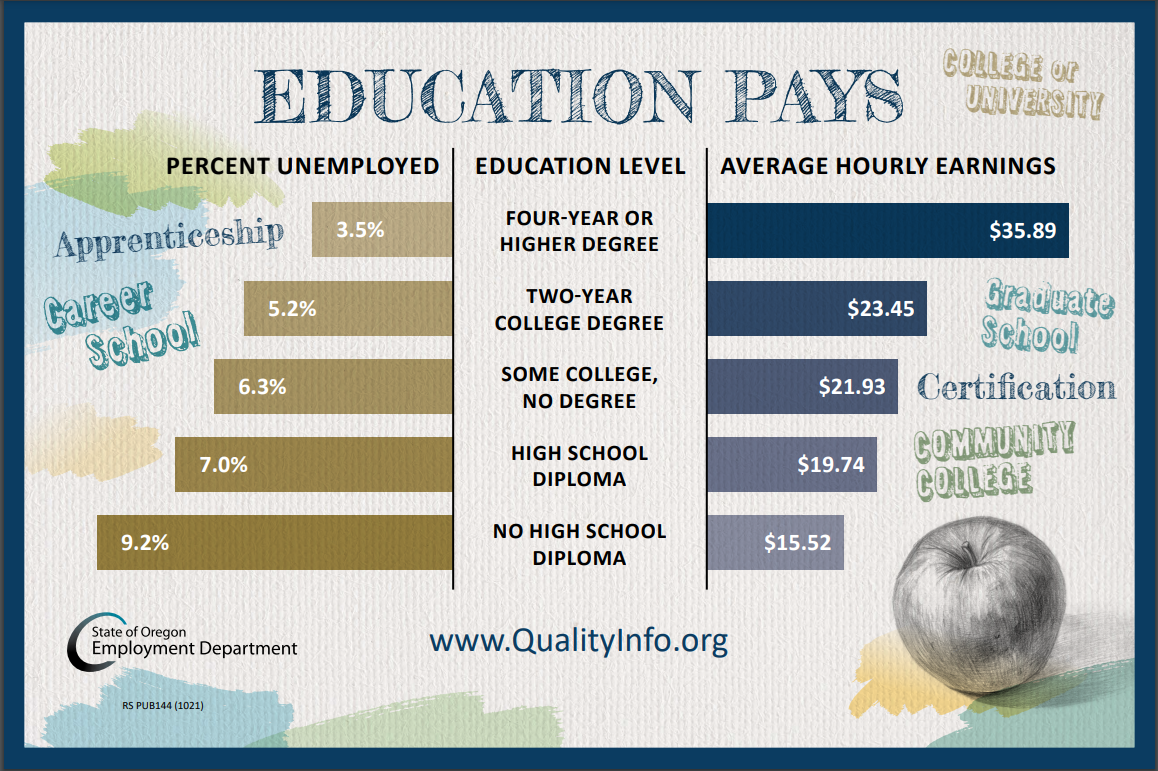

In the next half of this chapter, we turn our attention to education as a solution to social problems. We start with the question of money. Will an education actually make you rich? You may have seen the following chart as you were making the decision to go to college (figure 3.23):

Figure 3.23: Education can increase earnings and decrease unemployment, according to the State of Oregon Employment Department

This chart is commonly used in Oregon high schools and state unemployment offices to show that it pays to get a college degree. Clearly, people with a four-year degree or higher experience less unemployment and significantly higher hourly earnings than people with a high school diploma. Of course, these charts trumpet, everyone should get the most education they can, so they can make enough to buy houses and take care of their families. Is this the whole picture, though? Let’s look deeper.

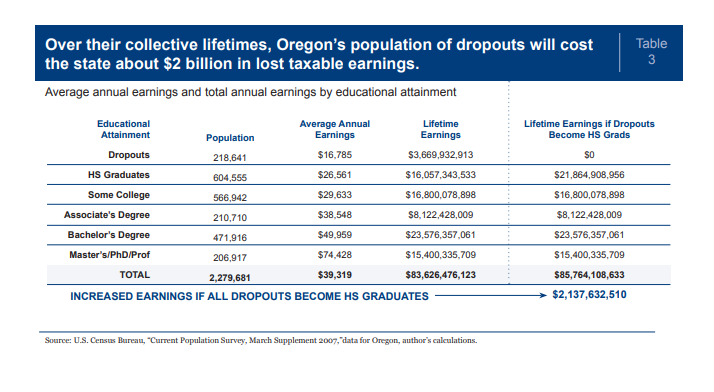

Figure 3.24 Costs of Dropping Out

When we compare the chart in figure 3.24 to the previous one in figure 3.23, we notice that the size of each group is not comparable. When we look at all the people who have bachelor’s degrees and more we are talking about roughly 700,000 people. When we look at the populations of high school dropouts, we see only 218,641. People with associate’s degrees are about 200,000 people, a relatively small pool. Given the significantly different sizes of the groups, percentages and average wages may be hiding significant differences between the groups.

Second, this chart hides alternate ways of training and education. Where are the plumbers and the electricians who attend training other than college? Where are the massage therapists, acupuncturists, and other health professionals who may not attend college and yet are highly trained professionals? What about cosmetologists, hairdressers, tattoo artists, musicians, and other creative workers who earn incomes often through self-employment and are not counted in unemployment statistics?

Third, when we look at unemployment data, we are only looking at people who are eligible for unemployment, not all people, not even all people who would be in the workforce if they could find work. This data then under-reports the number of people who may be looking for work but are no longer eligible for state or federal unemployment benefits. Even though definitions of who can be considered unemployed have expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall statistics don’t tell a complete picture.

Finally, what about differences in social location? Sociologists look more deeply at this data to explore whether combinations of gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, and neurodiverisity make a difference in access to education and educational outcomes, differences that this chart obscures. To answer some of these questions with theory, data, and experience, we need to introduce some sociological vocabulary.

3.4.1 Individual Improvement versus Class Improvement

A common saying for those who work to end poverty for families is that there are two ways out of poverty—education and savings. Is this really true for all families?

Sociologists differentiate between social mobility and structural mobility. Social mobility is the ability of a person or a family to change economic groups in their society. When we consider the dream of immigrants to the United States in the past and today, many say that their American dream is to work hard so that their children can have a better life than they do. When you consider your own family history, you may notice that you have more education than your grandparents or great-grandparents. Over time, individuals and families can get richer or poorer, moving between social classes. Education can contribute to social mobility.

Structural mobility is the ability of an entire class of people to become more wealthy or less wealthy. The efforts of the United Nations and other world service organizations to end extreme poverty would fall into the case of structural mobility. In general, industrialization has resulted in a higher standard of living for many people. Many people now have electricity and indoor plumbing, indicating some amount of upward structural mobility. However, global literacy and other educational measures are higher than they have ever been worldwide. If education was truly the only cause of structural mobility, we would see a reduction in poverty, and we don’t (Hanauer 2019).

3.4.2 Correlation and Causation

For that, we have to turn to two other social science concepts: correlation and causation. Causation in science is when a change in one variable causes a change in the second variable. Correlation, on the other hand, occurs when a change in one variable coincides with a change in another variable, but does not necessarily indicate causation.

For example, sociologists might measure how many churches and grocery stores there are. They might see that where there are more churches, there are also more grocery stores. They might conclude that because many churches host potlucks, dinners, and soup kitchens there is a need for more groceries. Alternatively, they might conclude that well-fed people go to church more often. However, there is a third variable at work—population. The more people live in a particular location, the more built environment there is likely to be, including schools, churches, grocery stores, and libraries. Population size drives causation, at this point, even though the number of churches and the number of grocery stores are correlated.

As we apply these concepts to education, our essential question deepens: To what extent do changes in education levels cause social or structural mobility?

3.4.3 Models of Education, Wealth, and Poverty

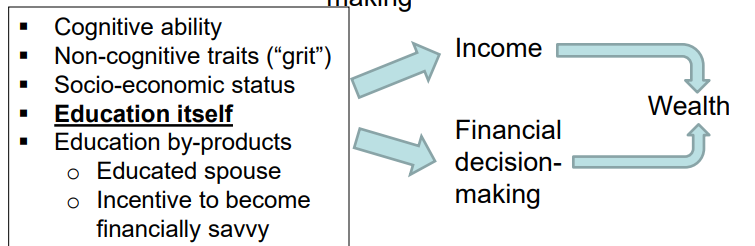

To answer this question, we look at this model, developed by economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. They propose the following relationship between education and wealth in figure 3.25:

Figure 3.25 Variables that impact wealth

There is a lot going on in this model, so let’s break it down together. In the first column, we see characteristics that influence further steps in the model. These characteristics include how smart you are, how persistent you are, your socioeconomic class, education itself, and the idea that you are likely to marry a similarly educated spouse. Not listed in the model is the idea that people from higher socioeconomic classes expect to live longer because they have access to good medical care, so they have some incentive to do financial planning (and extra wealth in the first place, so that they can save).

All of these factors increase income and lead to better financial decision-making. These two factors influence the acquisition of wealth, the total amount of money and assets an individual or group owns. This could include land, savings, stocks, buildings, or businesses, among other examples. This particular study concludes that it’s not education itself that directly leads to wealth. Rather, people who are wealthy already are more likely to have access to education and attain higher educational outcomes.

Figure 3.26 Educating girls reduces poverty

Global models, on the other hand, paint a slightly different picture. In figure 3.26, we see some young girls playing at school. The Borgen project highlights four ways in which educating women can reduce poverty. They find that educating women tends to lead to higher age at marriage and greater maternal health. Because more girls between the ages of 15 and 19 die from pregnancy complications than any other cause of death, increasing the age of marriage (and thus the age of first pregnancy) reduces mother and infant mortality. A second improvement is the increase in wages that a more educated woman can expect. With more skills, a woman can look for higher paying work, reducing poverty in her family and increasing economic stability. Third, when women make more money, they tend to spend that money on food and education for their children, strengthening the health of their entire families. Finally, educating women supports the overall health of entire communities because education allows women to be leaders in their communities (Borgen Project 2018).

When you consider, then, whether you should study for your next test, take the next class, or even go to college at all, the money that you might make can only be part of the reason.

3.4.4 Licenses and Attributions for Education Poverty and Wealth

Education Poverty and Wealth by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.23 “Oregon Education Pays” from the State of Oregon Employment Department is in the Public Domain.

Figure 3.24 “Over their collective lifteimes, Oregon’s population of dropouts will cost the state about $2 billion in lost taxable earnings” (pg. 15) in Oregon’s High School Dropouts: Examining the Economic and Social Costs by the The Foundation for Educational Choice State Research. Is in the Public Domain.

Figure 3.25. “Correlation vs. Causation: Three Theories. Theory Three” (slide 25) in Education and Wealth: Correlation Is Not Causation by William R. Emmons, Center for Household Financial Stability, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis is used under fair use.

Figure 3.26 Photo by Heather Suggitt. License: Unsplash License.