3.5 Education and Transformation

Unlike many of the social problems that we discuss in this class, the inequality in education is not just a social problem. At the same time, education can also be an answer to social problems. The ways in which individuals and communities empower themselves through education can transform their societies. To explore this, we will examine two approaches: education for liberation and crossing the digital divide.

3.5.1 Education For Liberation

Figure 3.27 Paulo Freire

Education serves a useful function, supporting people in learning, and participating with more choices in their societies. But education can also be a way for people in power to maintain their power, because schools themselves can be institutions of social control. By using segregation or by separating students into tracks, educational institutions reinforce social patterns of structural racism, sexism, homophobia, and other discriminatory practices. As a third option, education can also serve the purpose of liberation and healing. To explore this approach we turn to Paulo Friere, bell hooks, Brené Brown, and the educators and activists of the Open Oregon Project.

Paulo Freire was a sociologist, activist, and educator in Brazil and internationally from 1940 to his death in 1997 (figure 3.27). He founded and ran adult literacy programs in the slums of northeast Brazil. When he taught reading and writing, he used everyday words and concepts that his students needed to know for living well, such as terms for cooking, childcare, or construction. More revolutionary, though, was his idea that education could also be a force for liberation.

He believed and practiced that students and teachers could ask questions together about why things were the way they were in society. By arguing that the teacher was also a learner and that students were also teachers, he created classrooms in which students could feed their own curiosity and come to their own conclusions.

His most famous book is Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Pedagogy is the the art, science, or profession of teaching. Friere is looking at how teaching itself can empower oppressed people. In his book, he condemns the banking model of education, which he defines as “the concept of education in which knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing” (Freire n.d.). He argues that the banking model of knowledge is the most common but least useful form of education. He writes:

Education thus becomes an act of depositing, in which the students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor. Instead of communicating, the teacher issues communiques and makes deposits which the students patiently receive, memorize, and repeat. This is the “banking” concept of education, in which the scope of action allowed to the students extends only as far as receiving, filing, and storing the deposits. They do, it is true, have the opportunity to become collectors or cataloguers of the things they store. But in the last analysis, it is the people themselves who are filed away through the lack of creativity, transformation, and knowledge in this (at best) misguided system. Friere:72)

In contrast, his model of education emphasizes dialogue, action, and reflection. In dialogue, the students and the teachers have conversations about what they are learning and how they see things working in the world. Each person contributes from their own experience and knowledge. He writes, “To enter into dialogue presupposes equality amongst participants. Each must trust the others; there must be mutual respect and love (care and commitment). Each one must question what he or she knows and realize that through dialogue existing thoughts will change and new knowledge will be created” (Freire n.d.).

This dialogue is essential for learning and transformation, but it is insufficient as a social force. He argues that teaching and learning also require action and reflection. This combination of engaging in the world and then reflecting on what you learned, or praxis, is the true goal of education, creating a more equitable society by taking conscious action. He writes, “It is not enough for people to come together in dialogue in order to gain knowledge of their social reality. They must act together upon their environment in order critically to reflect upon their reality and so transform it through further action and critical reflection” (Freire n.d.).

His institute still influences educators and thinkers worldwide about how to use education to promote social justice.

Figure 3.28 bell hooks

Author and educator bell hooks, pictured in figure 3.28, built on the work of Paulo Friere, feminist theorists, and her own experiences as a Black woman to expand on this vision of the radical transformative power of education. In her book, Teaching to Transgress, she writes:

For black folks teaching—educating—was fundamentally political because it was rooted in antiracist struggle. Indeed, my all black grade schools became the location where I experienced learning as revolution.

Almost all our teachers at Booker T. Washington were black women. They were committed to nurturing intellect so that we could become scholars, thinkers, and cultural workers—black folks who used our “minds.” We learned early that our devotion to learning, to a life of the mind, was a counter-hegemonic act, a fundamental way to resist every strategy of white racist colonization. Though they did not define or articulate these practices in theoretical terms, my teachers were enacting a revolutionary pedagogy of resistance that was profoundly anticolonial. (hooks 1994:2)

Not only does she assert that education can be revolutionary in its approach and its outcomes, she argues that education is essentially done in community. Social transformation occurs within the context of an engaged classroom of learners. She writes, “Seeing the classroom always as a communal place enhances the likelihood of collective effort in creating and sustaining a learning community” (hooks 1994:8). Like Friere, she argues that a classroom is a community, and that teaching and learning transform the wider world.

Figure 3.29 Brené Brown

Similarly, Brené Brown, pictured in figure 3.29 focuses on creating brave classrooms. She is a researcher, teacher, author and change maker. Brown explains that educators are responsible for creating “a safe space in our schools and classrooms where all students can walk in and, for that day or hour, take off the crushing weight of their armor, hang it on a rack, and open their heart to truly be seen” (Brown n.d.)

We summarized Brown’s research approach in Chapter 2. Just as a reminder though, in her research she flips the traditional scientific model on its head, not starting with a fixed hypothesis, but starting with curiosity. In this grounded theory methodology, as originally developed by Glaser and Strauss, Brown asks people to tell their stories first, and then see what insights those stories yield. She writes, “We let the participants define the problem or their main concern about the topic, we develop a theory, and then we see how and where it fits in the literature” (Brown 2012:253).

Brown goes a step farther in seeing education as a force for healing and liberation. She writes that humans need to belong, and that classrooms are amazing places for that belonging to occur. Brown asserts that classrooms should be places where students and teachers alike can be brave, vulnerable, creative, and healing. She echoes the work of Friere saying that universities can be a source of transformational change:

To me, revolutionary change is tumultuous and difficult and requires a brand new lens for looking at the world. I think if there is anything that universities have the opportunity to do and have done incredibly well, it’s to help people try on new ways of being, look through new lenses, and understand new perspectives. (Brown 2017: video)

Each of these scholars and activists argues that education itself, when done in a transformational way, will create change in the student, in the teacher, in the classroom and in the wider world. With this approach, we see that education itself becomes a tool for addressing social problems.

Figure 3.30 Open Oregon Educational Resources Logo

In a final example, we explore the project from which this book arose as an exercise in transformation in learning. The Open Oregon Educational Resources organization, whose logo is pictured in figure 3.30, is a group of educators funded by the state of Oregon to create high quality educational resources for students. Through developing both textbooks and courses that center diversity, equity, and inclusion, this effort is making course materials more affordable and accessible for many students.

The project allows people who are normally excluded from the process of research and textbook creation to be included in the process. We are a collective of students, teachers, researchers, experienced academics, activists, and artists who are weaving our stories into books and courses that reflect and explain our social life. Because we share the work, some of us contributing a lot, and others of us only a few pages, many of us are able to tell our stories.

The approach itself is revolutionary, putting the power to create and share knowledge in the hands of ordinary people. Who would have imagined this in the early days of the first printing press?

3.5.2 Crossing the Digital Divide During COVID-19

Figure 3.31 The Digital Divide: How does it affect young people in London? [YouTube Video]

When you think about how often you use your phone to find a restaurant, get directions, or look up the actors in your favorite movie, you are using technology to solve problems. However, access to technology is unequal. This inequality is called the digital divide, describing not only internet use but access to computers and smartphones, access to free or low-cost, stable internet, and digital literacy. These three components of device, access, and effective skills are referred to as the three legged stool needed to close the digital divide. Individuals need a computer that they know how to use effectively and sufficient quality internet service to participate effectively.

Please take a moment to watch the video in figure 3.31. As you watch, consider how the digital divide affects the young people in this video and some of the solutions the video proposes to bridge the divide.

Since the first known usage of digital divide in 1994, researchers have examined who is divided. As you might expect, socioeconomic class is a strong predictor of who has access to technology and the internet. In early research, geographic location predicted where you landed in the divide. Residents of bigger cities were more likely to have internet access. City dwellers in poor neighborhoods and rural residents were less likely to have access. Race, ethnicity, gender, and age also impacted access to technology and training. The digital divide itself is a manifestation of a social problem, both because it impacts people worldwide, and because there is significant inequality based on people’s social location.

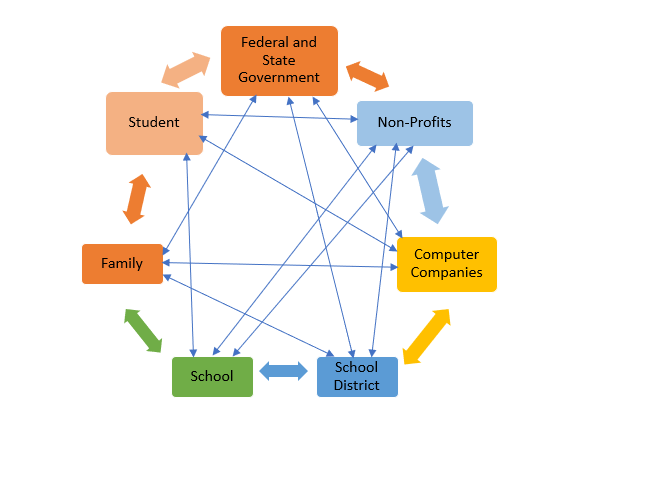

As we discussed earlier in this chapter, families have had widely different experiences of education during COVID-19, based often on their ability to access resources for learning. Unlike many social problems which got worse during COVID-19, efforts to close the digital divide accelerated during the pandemic. Also, it’s not that people are protesting in the streets to create social change in this area. Instead, we see a wide array of government, corporate, nonprofit, and community agencies working together to provide access to online education. Each of the partners contributes something unique to getting all of our students and their families back in the classroom. Also, as each partner contributes a part of the solution, the other partners respond and react, illustrating the interdependent nature of solving social problems and highlighting that they must be solved collectively.

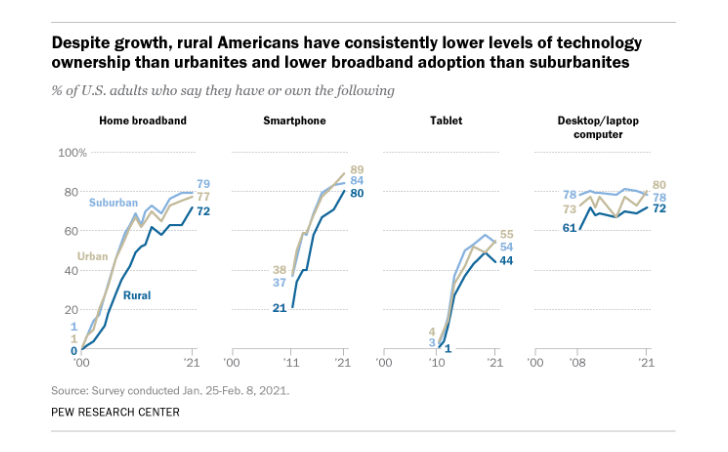

As early as 2018, Pew Research was reporting that nearly one in five students couldn’t finish their homework because they didn’t have access to the internet (Pew 2018). When you look at the gap across gender, race, class, and ability/disability, the gap is closing. The graph in figure 3.32 shows widespread adoptions of technology between 2000 and 2021 in all geographic locations. People in rural areas still own less technology than people who live in cities or suburbs.

Figure 3.32 Despite growth, rural Americas have consistently lower levels of technology

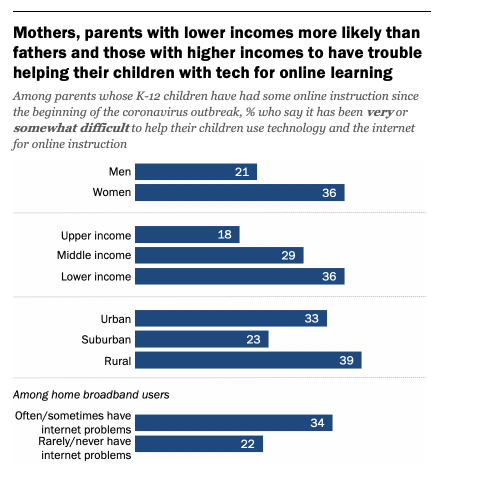

You may have experienced going on line for school during COVID-19. Because many schools closed, online education became critical for providing education. This made the digital divide more visible. Many parents struggled to help their kids with technology, as shown in figure 3.33. When we examine this detail, we see that women, people with lower incomes, and rural families struggle the most with this problem.

Figure 3.33 Mothers and parents with lower incomes have trouble helping their children with technology.

At the same time our society worked to create interdependent solutions to closing the digital divide so that students could learn. Students and families acted with individual agencies to buy computers and learn how to use them better. Federal and state governments and individual school districts acted with collective action to provide money to improve internet access and distribute internet equipment. Nonprofit organizations and computer companies provided training and technology for adults who weren’t going to school. Schools and teachers moved classes online quickly so that students could learn. The figure in 3.34 shows the connections that enabled interdependent solutions. Let’s examine these actions in more detail.

Figure 3.34 Interdependent solutions to educational access during COVID-19, Figure 3.34 Image Description

Among many federal government responses to COVID-19, two specific efforts are useful to mention. First, the federal government launched the Emergency Broadband benefit program in February 2021, paying a portion of the internet bill for low-income families. This program also allowed school districts and school libraries to apply for grants to buy and support computers, hotspots and internet connectivity. The program transitioned to the Affordable Connectivity Program in March 2022, expanding the program to more households, adding Pell grant recipients and free lunch program students as potential recipients, and stabilizing government funding for this program.

Second, the federal government funded the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund (or GEER Fund) in 2020. These funds were allocated to each state to stabilize education in that state during the pandemic. The governors in each state chose how to spend those funds to help students, families, teachers, and schools. In Oregon and at Oregon Coast Community College, we see GEER money being used in multiple ways. OCCC distributed some money directly to students in need. The college purchased laptops and hotspots for student use. Statewide, GEER money was used to fund the Open Oregon Guided Pathways project (of which this book is a part), to create free sociology, criminal justice, and human development and Family Science textbooks and courses for all students. Each state is applying federal GEER money differently. Do you know what is happening in your state?

Together, the federal government and the state of Oregon are managing the e-Rate program, a program that funds internet access for schools and school libraries. These and other government-funded programs are supporting schools to step up to be actors in closing the digital divide.

Nonprofit social service providers highlight digital skills as a support to stabilizing families. Goodwill, for example, hosts a digital learning platform called GFCLearnfree.org, which hosts educational content that helps people learn to use their computers, search for jobs online, and manage their money more effectively. However, access alone does not help people learn effectively. Some nonprofits are taking a much more integrated approach.

EveryoneOn is a U.S.-based nonprofit that takes a multifaceted approach to closing the digital divide. They were founded in 2012 to meet the federal government’s challenge to digitally connect everyone. They developed a locator application which allows people to find low-cost internet services in their area. This expanded into an online locator tool that not only highlights internet services, but also provides options for purchasing low-cost computers.

In addition to this technology differentiator, EveryoneOn builds partnerships to support digital literacy. They partner with technology companies in local areas to provide the devices and technology support at no cost to program participants. They also partner with local service providers who connect them with the people who need their services. Finally, they provide digital literacy training to low income people. Their initial offering was an on-ground class to help senior citizens in Miami to use their phones more effectively.

As a response to the pandemic, they developed a hybrid model, in which clients get initial support for their new computers in person from EveryoneOn and their service provider. Then EveryoneOn provides online classes that teach how to use Zoom, how to send email, and how to keep personal information safe among other digital literacy skills. This organization is particularly committed to closing the digital divide among communities of color and providing services in Spanish and English. The community that EveryoneOn is growing is essential in translating policy and funding into action.

Finally, we see individuals taking action to close the digital divide. You, yourself, may be a person who now knows how to use Zoom or Google slides to do your school work. You may be a parent with a child who needs to log in to be at a school every day. You may be a teacher who is working fast to create learning opportunities that work for your student. Or, you may be a person who is creating applications which help the rest of us. In Chapter 7, we will look at how one person created an application to connect senior citizens to vaccine appointments.

Although we still have work to do, the response of educators, business, nonprofits, and government is adding even more people to the digital superhighway. Although the digital divide is far from closed, the interconnected responses across individuals and institutions is a reason for hope.

3.5.3 Licenses and Attributions for Education and Transformation

“Education and Transformation” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.27 Photo by Paulo Freire is in Public domain.

Figure 3.28 Bell Hooks by Alex Lozupone. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 3.29 Brené Brown image from Brené Brown.com. Is used under fair use.

Figure 3.30 Open Oregon Educational Resources Logo by Open Oregon Educational Resources. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.31 “The Digital Divide: How does it affect young people in London?” by XLP London. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

Figure 3.32. “% of U.S. Adults Who Say They Have or Own the Following” in Some digital divides persist between rural, urban and suburban America © Pew Research Center. License: Pew Research Center License.

Figure 3.33 “% Who Say it Has Been Very or Somewhat Difficult to Help Their Children use Technology and the Internet For Online Instruction” in Parents, their children and school during the pandemic © Pew Research Center. License: Pew Research Center License.

Figure 3.34 Interdependent Solutions to Education during COVID-19 by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.