4.3 Houselessness, Housing Insecurity and Social Location

People are unhoused because they do not have access to adequate, affordable housing. For every 100 extremely low-income renters, there are just 31 affordable units (National Coalition for the Homeless 2020). People who are housing insecure are at risk of losing their housing because they lack adequate resources to meet basic needs.

Social location, where identity and power connect, such as class, race, gender, age and physical ability, can impact housing stability. In this section, we’ll apply theories of social stratification and intersectionality to the problem of houselessness and housing insecurity. Let’s start by exploring the sociological concept of class.

4.3.1 What is Social Stratification?

|

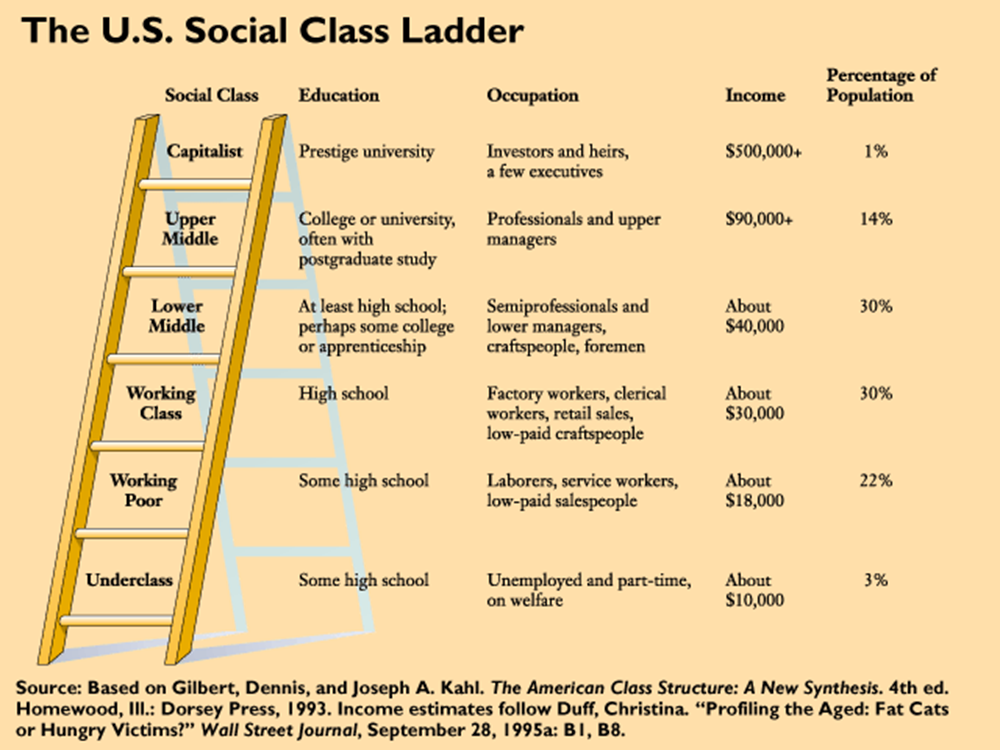

As you might remember from Chapter 2, the discipline of sociology arose during a time of great social, economic, and political disruption. Then, like now, sociologists group people according to how much they have. However, sociologists consider more than money in their definition. Instead, they define stratification as a socioeconomic system that divides society’s members into categories ranking from high to low, based on things like wealth, power, and prestige. Systems of stratification can be as extreme as slavery or apartheid. They can be as long-lasting as caste. Or they can be as common as class, a group that shares a common social status based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation. As you might remember from Chapter 3, wealth includes anything that you own—your house, your car, and perhaps your inheritance from your great-grandmother. Income is the money a person earns from work or investments. Income may include your paycheck or royalties from the book that you wrote. Another term to reference this combination of factors is socioeconomic status (SES). Socioeconomic status is an individual’s level of wealth, power, and prestige. Karl Marx, the German philosopher introduced in Chapter 2, focused on ownership of wealth or businesses as a way of defining class. In his model, workers who own nothing except maybe the clothes on their back would always be in conflict with the rich, those who owned businesses and property. Max Weber, another German sociologist from Chapter 2, added ideas of skill status and power to the concept of class. 4.3.1.1 Class System in the United StatesThe numbers in figure 4.6 are a little dated, but the chart remains valuable because it looks at more than just money. One of the tenants of the American dream is that if you work hard, you can have a better life. Because class consists of education, income, wealth, and occupation, it is possible to move up in class.

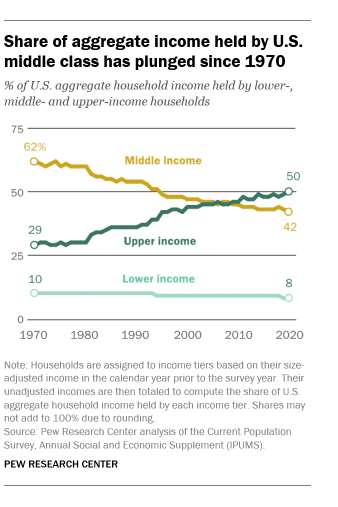

Figure 4.6 The U.S. Social Class Ladder, Figure 4.6 Image Description However, what we see in reality is that the middle class in the United States is slowly shrinking, as shown in the chart in figure 4.7. The people in upper-income households are earning significantly more. More people are becoming downwardly mobile, moving into the lower class. For more details on this transition, you can explore this report from Pew Research: “How the American Middle Class Has Changed in the Past Five Decades.”

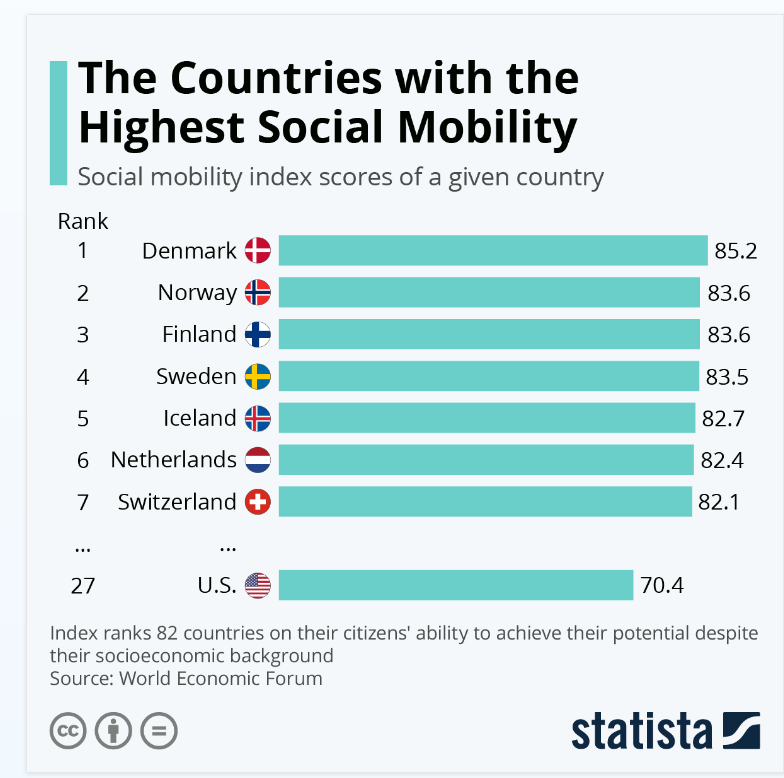

Figure 4.7 Share of income of the middle class has plunged 4.3.1.2 The Nordic Model: Supporting Social MobilityOne of the ways to measure the persistence of class is to look at how easy it is for children to experience a difference in social class from their parents. This concept is called social mobility, or the ability to change positions within a social stratification system. The United States has some social mobility, but not as much as you might expect given the prevalence of the American Dream, an American social ideal that stresses egalitarianism and especially material prosperity (Mirriam Webster, n.d.), in our national culture. Instead, we find that the Nordic region, which includes Denmark, Norway, Finland, Sweden, and Iceland, experience the highest social mobility.

Figure 4.8 Countries with the highest social mobility In these top five countries, the Nordic model uses a capitalist economic model and a strong social safety net. People own their own businesses and employ workers. In addition, citizens pay high taxes, so that everyone experiences a safety net when parenting, disabled, unemployed, or retired. To learn more about the pros and cons of this model, you might want to read this blog: “The Nordic Model: Pros and Cons.” |

4.3.2 Social Class and Housing

As you might expect, communities with high poverty rates tend to have high rates of unhoused people. Housing stability is a prerequisite for class mobility (Ramakrishnan et al. 2021). Correlations between social location and housing stability and reveal some of the ways social mobility can be limited by race, gender and age. Home ownership is also a milestone for upward mobility, so long as the homeowner is not cost burdened. Whether we rent or own, housing is generally a household’s largest expense. For people who own, though, their house payments become an investment with the possibility of generating more wealth over time.

4.3.3 Race

In 2020, the nationwide Point-in-Time Homeless Count identified 580,466 people who were unhoused, and of these 280,612 were White. So it can be said that in the U.S. there are more unhoused people who are white than Black, Hispanic, Native American or Asian. However, since people who are Black account for only 13% of the total U.S. population, but they represent 30% of the unhoused population, we can say that race has something to do with houselessness and housing insecurity. People who Native American and Native Alaskan, people who are Latinx or Hispanic, and certain groups of people who are Asian and Pacific Islanders also experience disproportionate rates of houselessness and housing insecurity.

Whenever a social problem impacts members of a specific race at a higher rate than the general population, we can say that racial inequity exists. Ibram X. Kendi asserts that any policies that result in racial inequity and ideas that justify or excuse racial inequity are racist. In Section 4.5 we will look closer at racist housing policies and ideas behind the history of displacement and exclusion that creates and sustains these racial inequities. In section 4.6 we will look at how antiracist policies are essential to ending houselessness and housing insecurity in the U.S.

4.3.4 Gender and Houselessness

Figure 4.9 Photo: All families deserve a home

70% of people who are unhoused identify as men (National Alliance to End Homelessness 2021), most of them in their 50’s and 60’s meet the definition of chronically homeless. During 2021, in Los Angeles County, California, 83% of the 1800 unhoused people who died were men. Most of those deaths were classified as preventable (Dolak 2022). Women have lower rates of homelessness overall, but are more likely to face housing insecurity. They are more likely than men to be unemployed and renters. This increases their risk of becoming severely cost-burdened by housing (Zillow 2020).

People in families with children make up 30 percent of the homeless population, and most unhoused single parents are women. Unaccompanied youth (under age 25) account for another 30% of unhoused people. 40% of unaccompanied, unhoused youth identify as LGBTQIA+. The long term impacts for youth who are unhoused include significantly higher rates of emotional, behavioral, and immediate and long-term health problems, along with increased risks for substance use and suicide (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration 2021). They have numerous academic difficulties, including below-grade level reading, high rate of learning disabilities, poor school attendance, and failure to advance to the next grade or graduate. Four out of five children who are experiencing homelessness have been exposed to at least one serious violent event by age 12.

Socially constructed ideas of normal or acceptable identities are barriers to many people in accessing shelter, housing, and many other services. Specifically in the case of houseless shelters, transgender women may be refused admittance by the women’s shelter and at risk of violence at the men’s shelter (NCTE 2019).

4.3.5 Licenses and Attributions for Houselessness, Housing Insecurity and Social Location

“Houselessness, Housing Insecurity and Social Location” by Nora Karena and Kim Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.6 Social Class Ladder: http://6h6ancientrome.weebly.com/uploads/1/2/2/2/12222825/8017898.gif?533 (need open source version)

Figure 4.7”Share of aggregate income held by U.S middle class has plunged since 1970” in How the American middle class has changed in the past five decades © Pew Research Center. Used under fair use.

Figure 4.8 “The Countries with the highest social mobility” by Willem Roper. License: CC BY-ND 3.0.

Figure 4.9 Photo byChewy. License: Unsplash License.

CC-BY-4.0 Elizabeth Pearce Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens

Whose Family has a Home? From Fair Housing Act section https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/families/chapter/finding-a-home-inequities/ lightly edited and Indigenous People and Reservation Land: https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/families/chapter/finding-a-home-inequities/ Lightly edited