5.5 Climate Change: Interdependence, Individual Agency and Collective Action

When we look at the problems of climate and environment, the sheer size of the issues can be disheartening. These issues are difficult to resolve, in part, because their causes and solutions are interdependent. For example, people in the US need oil to create gasoline for cars and fuel for industry. This voracious need encourages oil companies to produce oil efficiently. Industrial efficiency may incentivize some companies to choose to use gas flaring in Nigeria. The causes of environmental degradation are linked in both obvious and subtle ways.

Solutions to environmental issues, particularly when they are effective, also reveal the power of our interdependence. Making a difference with this social problem requires both/and thinking – both individual agency and collective action. Let’s explore examples that look at collective action taken on regional, national, and international scales.

5.5.1 The Oregon Bottle Bill

Figure 5.15 The Oregon Bottle Bill was the first law that created deposits for bottles. Do you think it has made a difference?

When I was in college in the 1990s, I belonged to an organization known as OSPIRG, the Oregon Student Public Interest Research Group. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the group was instrumental in environmental activism in the state. They advocated for laws and policies that would reduce consumer pollution. Their legacy includes the Oregon Bottle Bill.

The law, formally known as the Beverage Container Act of 1971 was signed into law by then Oregon governor, Tom McCall. With the support of other environmental groups and the legislature, this law became the first one in the nation to provide deposits on bottles and cans, encouraging people to return them rather than throw them away. The concept was both revolutionary and effective. In this post from the Oregon Historical Society, we see the consequences of this law, both then and now:

The Bottle Bill instantly reduced litter in Oregon. The share of beverage containers in roadside litter in the state declined from 40 percent before the law was passed to 10.8 percent in 1973 and 6 percent in 1979. The Bottle Bill also reinforces the practice of recycling. In the 2000s, about 84 percent of beverage containers were recycled, helping to make Oregon fourth in the nation for its rate of recycling. (Henkles 2022)

In the case of action in one small state, activists, beverage manufacturers and bottlers, grocery store owners and clerks, the legislature, and the governor all had to come to a shared agreement about what to do about the problem of pollution. This new law had to be implemented and advertised through the media. For decades, grocery stores had to collect the initial refunds, process the bottles, and return the money back to consumers. You may have even had a job that required you to handle these sometimes gross empty bottles.

From a relatively small beginning, the impact of this state law has grown. Multiple US states have enacted similar laws. The bottle bill has even grown in Oregon. The most recent iterations established bottle drops, a more efficient and hygienic way to process bottles and cans. Solving the problem required using our interconnectedness effectively, and the consequences continue to ripple out into the world.

5.5.2 Indigenous Resistance

Indigenous resistance to colonialism and climate destruction has occurred and continued around the world since the arrival of colonists. Generally speaking, Indigenous cultures are rooted in place, tradition, and stewardship of the land. Because there are Indigenous peoples on every acre of land that is habitable or has been habitable by humans, this means that each act of destruction to the environment is also an act of destruction for the Indigenous peoples who are from there.

Figure 5.16 Indigenous World View Can Preserve Our Existence [YouTube Video]. Please watch this 2:53 minute video. How does the video describe the power of the indigenous world view?

You have probably read that over Indigenous people currently steward 80% of the world’s biodiversity. This is true, but only because Indigenous peoples both resisted exploitation and created new systems for protecting the land, its inhabitants, and their cultures. And, as stated before, these acts of resistance continue today.

Figure 5.17 Standing Rock, North Dakota. Water Protectors protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline.

A popular example of Indigenous resistance in the United States was the #NoDAPL protests, otherwise known as Standing Rock. The picture in figure 5.17 shows Indigenous Water Keepers, protecting the water. The NoDAPL movement began when Standing Rock Sioux peoples decided to fight the construction of a pipeline, known as the Dakota Access Pipeline, that would be built on their ancestral land, destroy cultural resources, and violate century old treaties made between the tribe and the U.S. government. This led to intense protests where Indigenous peoples, allies, and community members from all over the world came to occupy and resist the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. More than 300 people were injured and hundreds were arrested during these protests by the U.S. government (Montare 2018). While the Dakota Access Pipeline is still in commission, the NoDAPL movement paved the way for many contemporary Indigenous resistance movements in North America, such as #StopLine3 and Stop Enbridge: Protect the Gulf Coast!

Figure 5.18 Zapatista Movement In 1998, Zapatista women in Amador Hernadez, Southern Mexico, demanded daily that the Mexican military leave the village communal landholdings. (Photo by Tim Russo)

Another historical example of Indigenous resistance is the Zapatista movement (figure 5.18) In 1994, an Indigenous armed organization named the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), declared war on the Mexican Government. Their demands were for “work, land, housing, food, health, education, independence, liberty, democracy, justice and peace.” This uprising began in Chiapas, Mexico as an occupation of land and continues to this day. The Indigenous peoples along with some politically-aligned non-Indigenous peoples still assert sovereignty over their economic, social, and cultural development. The Zapatista movement is a current example of how Indigenous communities can defend their lands, cultures, and each other.

5.5.3 Paris Climate Agreements

Our interdependence is also reflected at the other end of the scale of social change. In 2015 the United Nations brokered an international treaty known as the Paris Agreement. The goal of the agreement is to limit the emission of greenhouse gasses. By limiting these emissions the agreement strives to prevent additional global warming. This worldwide agreement was signed by 196 parties when it initially became a treaty. The United Nations writes this about the Paris agreement:

The Paris Agreement is a landmark in the multilateral climate change process because, for the first time, a binding agreement brings all nations into a common cause to undertake ambitious efforts to combat climate change and adapt to its effects. (United Nations 2022)

The core components of the agreement are:

- Countries will enact limits on greenhouse gas emissions for their countries by 2020

- Countries will also develop energy alternatives that reduce emissions.

- Finally, countries that need help will receive financial, technological, and infrastructure assistance.

As you might expect, the implementation of this agreement is complicated. Some environmentalists argue that the agreement doesn’t move fast enough to create the needed changes. When measuring progress in the five years since the agreement, the American Association for the Advancement of Science reports mixed results. On one hand, the implementation of some of the limits is starting to slow the emissions of greenhouse gasses. On the other, the United Nations has very little money to enforce the agreements, and countries, such as the United States, can leave the agreement at any time.

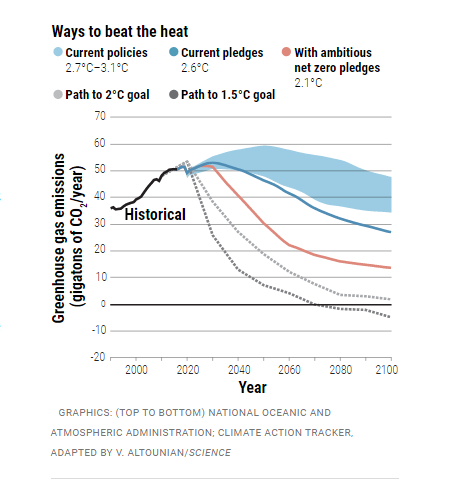

Figure 5.19 Greenhouse Gas emissions – goals, progress, and vision

The chart in figure 5.19 shows both the goal for emissions and our progress. If we stay with current policies shown in the blue shaded area, the greenhouse gas emissions would result in approximately a 3 percent increase in global temperature. If we actually do the work specified in the Paris Agreement, temperatures would only rise by 2.6 degrees Celsius. Most climate scientists believe we need to do more to sustain life.

Even though progress is uncertain, the act of global solidarity is unprecedented. Global leaders are recognizing our shared interdependence. They are acting on a global scale to make a difference.

5.5.4 Licenses and Attributions for Climate Change: Interdependence, Individual Agency and Collective Action

“Climate Change: Interdependence, Individual Agency and Collective Action” by Avery Temple and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.15 Photo by Aleksandr Kadykov License: Unsplash License.

Figure 5.16 “Indigenous World View Can Preserve Our Existence” by Morobe Development Foundation.License Terms: Standard YouTube License.

Figure 5.17 Standing Rock, North Dakota Water Protectors by NoDAPL Archive. License:CC BY-SA 4.0 [i]

Figure 5.18 Photo of Zapatista Women (Photo by Tim Russo) in A Spark of Hope: The Ongoing Lessons of the Zapatista Revolution 25 Years On by Hilary Klein, North American Congress on Latin America is used under fair use.

Figure 5.19 “Greenhouse Gas emissions – goals, progress, and vision” in The Paris climate pact is 5 years old. Is it working?, by Warren Cornwall, Science is used under fair use.