7.3 Epidemiology in the U.S.: Health Disparities by Social Location

Doctors and medical professionals focus most on the health of an individual person. Sociologists and public health professionals focus on the health of groups. This specialty is called epidemiology, the study of disease and health, and their causes and distributions. Epidemiology can focus on the differences between neighborhoods, states, or even countries. As we look at health in the United States, we see a complex and often contradictory issue. On the one hand, as one of the wealthiest nations, the United States fares well in health comparisons with the rest of the world. However, the United States also lags behind almost every industrialized country in terms of providing care to all its citizens. This gap between the shared value of health and unequal outcomes makes health and illness a social problem.

Sociologists and others who study human health have a detailed model that helps them make sense of health in groups. This model is called the social determinants of health. More specifically, the social determinants of health are the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work, and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness. While ethnicity may seem to correlate with these elements, it is misleading to assume that all members of a specific racial group will experience the same health outcomes (Jones & Whitemarsh 2010). These circumstances are in turn shaped by a wider set of forces: economics, social policies, and politics.

7.3.1 Diversity and Inequality: Social Determinants of Health

|

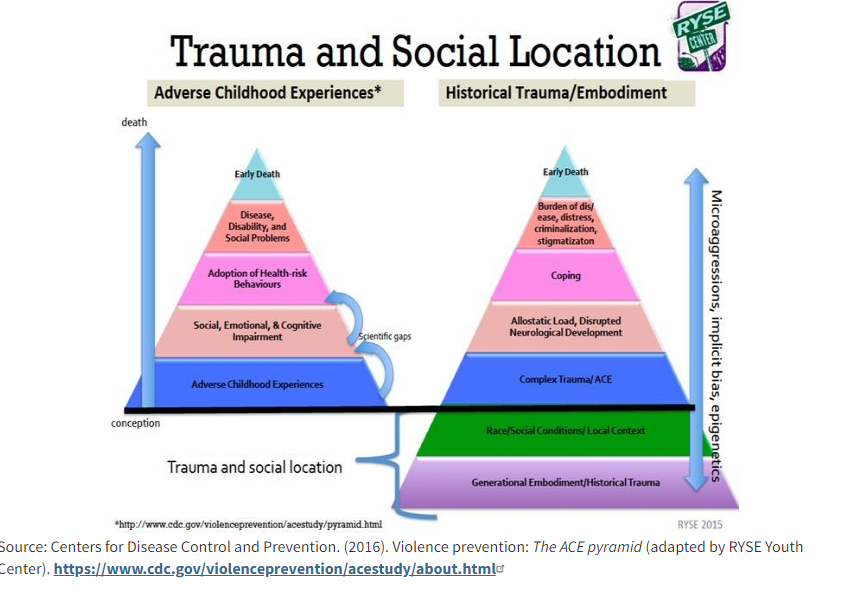

Figure 7.6 Social determinants of health (SDOH), provided by the CDC. Figure 7.6 Image Description Social scientists and health professionals use this model of social determinants of health to describe the social factors that influence the health or lack of health of different social groups. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) created the model in figure 7.6.We see that access to quality health care influences how healthy you might be. Whether your neighborhood is located next to an oil refinery, as described in Chapter 5, changes your health outcomes. You might be suprised to see that education access and quality also impacts your health. However, you might remember from Chapter 3 that education and wealth are correlated. When you know more, you might chose to make different health decisions. The way organizations and institutions create models for the social determinants of health can change what we see. If you’d like to explore this question more deeply, here is a model from the World Health Organization and a SDOH model from the Canadian First Nations Peoples. Why might these models be different from each other? In a slightly different model, researchers look at why how trauma over time makes a difference in health outcomes:

Figure 7.7 Trauma and Social Location The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides the pyramid model in figure 7.7 on the left. This pyramid starts with Adverse Childhood Experiences, more commonly known as ACEs. These adverse or traumatic experiences may include growing up in a family with mental health or substance abuse issues, child abuse, or other experiences of violence. Because a person who experiences these events is more likely to experience some impairments in childhood, they are more likely to adopt risky behaviors as an adult. If left untreated, the related diseases and disabilities can lead to early death. When children get help from caring adults, are connected with others, or receive competent professional support, they can recover from this early trauma. Also, many people experience at least one Adverse Childhood trauma in their lifetime. However, a more marginalized social location may create risks for experiencing more ACEs. For a deeper look at how ACEs work, you could watch this TED Talk, “How Childhood Trauma Affects Health Across a Lifetime.” The pyramid on the right, created by The RYSE Youth Center center adds a deeper context to the causes of Adverse Childhood Experience (ACEs). They identify historical trauma, pointing out that trauma can be repeated through generations and across history, and that long-term, strained social conditions can increase the incidence of ACEs in specific populations. The more ACEs an adult has can predict that person’s risk of developing health problems such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. This addition helps us to understand even more deeply that disease and health are interdependent social problems. |

7.3.2 Health Inequalities by Race and Ethnicity

When looking at the social epidemiology of the United States, it is easy to see the disparities among races. The discrepancy between Black and White Americans shows the gap clearly.In 2018, the average life expectancy for White males was approximately five years longer than for Black males: 78.8 compared to 74.7 (Wamsley 2021). (Note that in 2020 life expectancies of all races declined further, though the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic was a significant cause.)

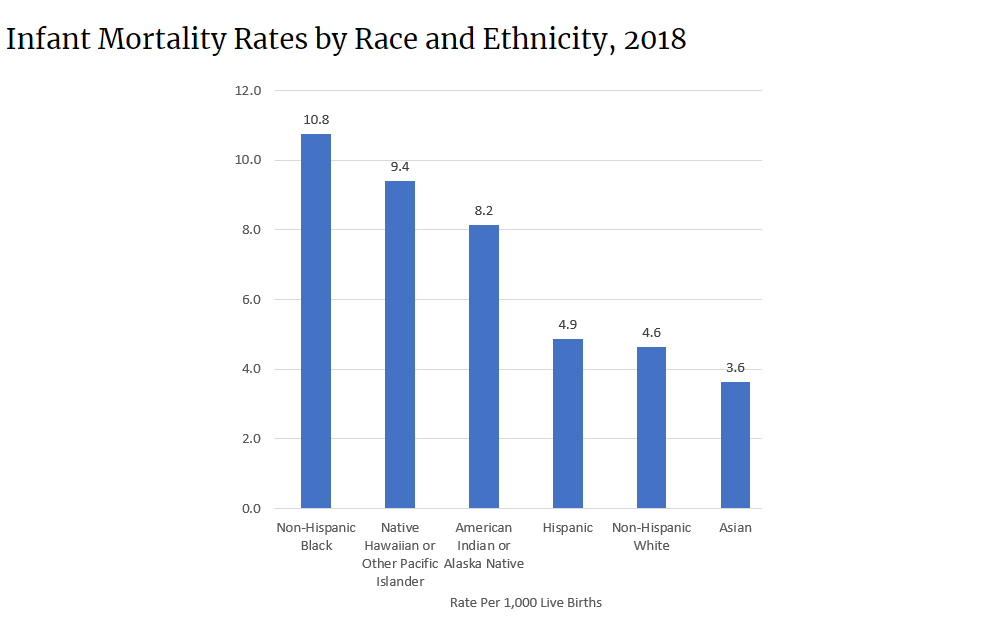

Mortality is the measure of how many people die at a particular time or place. When we look at how many babies die, or infant mortality, we see similar disparities. The 2018 infant mortality rates for different races and ethnicities are as follows:

Figure 7.8 Infant Mortality by Race and Ethnicity, 2018. Figure 7.8 Image Description

According to a report from the Henry J. Kaiser Foundation (2007), African Americans also have higher incidence of several diseases and causes of mortality, from cancer to heart disease to diabetes. In a similar vein, it is important to note that ethnic minorities, including Mexican Americans and Native Americans, also have higher rates of these diseases and causes of mortality than White people.

Lisa Berkman (2009) notes that this gap started to narrow during the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, but it began widening again in the early 1980s. What accounts for these perpetual disparities in health among different groups? Much of the answer lies in the level of healthcare that these groups have access to. The National Healthcare Disparities Report shows that even after adjusting for insurance differences, Black, Indigenous, and people of color receive poorer quality of care and less access to care than dominant groups. The report identified these racial inequalities in care:

- Black people, Native Americans, and Alaska Natives receive worse care than Whites for about 40 percent of quality measures, which are standards for measuring the performance of healthcare providers to care for patients and populations. Quality measures can identify important aspects of care like safety, effectiveness, timeliness, and fairness.

- Hispanics, Native Hawai`ians, and Pacific Islanders receive worse care than White people for more than 30 percent of quality measures.

- Asian people received worse care than White people for nearly 30 percent of quality measures but better care for nearly 30 percent of quality measures (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2020).

Although the reasons for these disparities are complex, a simple illustration may help make the point. Medical professionals and public health workers are asking why Black and Brown people are more likely to die of COVID-19. One medical study examined the pulse oximetry measurements of Black people and White people who were in the hospital. If you’ve been to the hospital, you likely have had to put your finger into a little device that tells the medical professionals how much oxygen is in your blood, or oximetry. The authors of the study examined how often these measurements were accurate for White patients and Black patients. They found that Black patients were three times more likely than White patients to have shortages of oxygen in the blood that the monitor didn’t pick up. Because COVID-19 mainly attacks the lungs and reduces oxygen, the discrepancies in the measurements of this device may lead to more medical complications in Black patients (Sjoding et al. 2021). Although there are multiple complex reasons, this example can help illustrate part of the reason. Sometimes medical devices work more effectively for people with white skin. An example of this is research that suggests that pulse oximeters work less effectively for darker-skinned people, and as a result, may actually cause more harm than good.

7.3.3 Health Inequalities by Socioeconomic Status

The social location of wealth or poverty often influences health outcomes (Patel 2020). Marilyn Winkleby and her research associates (1992) state that “one of the strongest and most consistent predictors of a person’s morbidity [incidence of disease] and mortality [death] experience is that person’s socioeconomic status (SES). This finding persists across all diseases with few exceptions, continues throughout the entire lifespan, and extends across numerous risk factors for disease.” In other words, having a lower SES makes you more likely to get sick or die of disease than people with a higher SES.

In Ijaoma Oluo’s blog post, “So You Want to Talk About Race,” the author describes her experience as a child in Japan, and how being poor changes both a current healthcare crisis for her mother and her own ability to eat without pain. She writes that when you are poor, the only option you have when a tooth goes bad is to get it pulled. Even if you get richer as an adult, your mouth tells the story of your poverty, because it is full of gaps. (Oluo 2022).

Economics is only part of the SES picture. Research suggests that education also plays an important role. Phelan and Link (2003) note that many behavior-influenced diseases like lung cancer (from smoking), coronary artery disease (from poor eating and exercise habits), and HIV/AIDS initially were widespread across SES groups. However, once information linking habits to disease was disseminated, these diseases decreased in high SES groups and increased in low SES groups. This illustrates the important role of education initiatives regarding a given disease, as well as possible inequalities in how those initiatives effectively reach different SES groups.

To find data related to why people of low SES are more likely to contract and die from COVID-19, we look outside the United States to a study conducted in England. The study finds that people who are poor are more likely to live in overcrowded or substandard housing. These conditions make it challenging for the people who live there to quarantine effectively or maintain social distancing.

According to this study, people who are poor are more likely to be essential workers – servers, grocery clerks, delivery drivers, and other service workers. These essential workers have been required to keep their jobs and continue their interactions with lots of other people, again increasing their risk of exposure to the virus.

Finally, because people with a lower socioeconomic status experience financial insecurity, they can be more stressed. This stress often translates into weakened immune systems, which makes it difficult to fight the virus. Finally, because poorer people have less access to quality healthcare, they may delay going to the hospital. Because they waited “until the last minute” to get medical attention, their symptoms are more severe, and it is more difficult for them to recover.

7.3.4 Health Inequalities by Biological Sex

-Professor Sarah Hawkes, Co-Director of GH5050

Figure 7.9 Gender and COVID-19 Quote

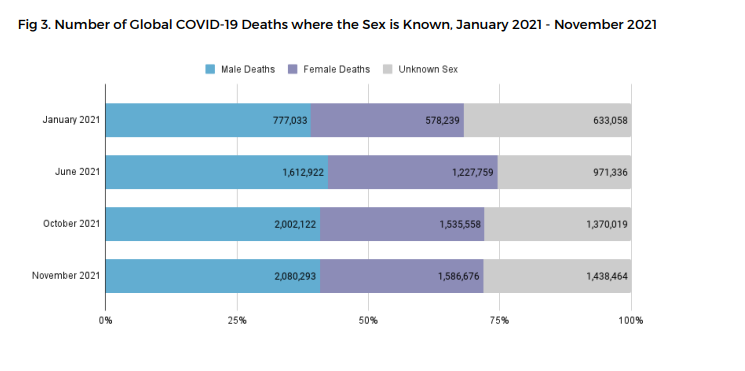

Exposure, sickness, and death due to COVID-19 do not only reflect structural inequalities for People of Color but are also influenced by one’s gender. In A Gender Perspective on COVID-19 [YouTube Video], the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace, and Security highlights some of the ways that females may experience COVID-19 differently than males. They explain that during the pandemic, women are more likely to be caregivers for family members and work as frontline health workers compared to men, increasing their risk of exposure. At the beginning of this crisis, the video focuses on “front-line first” encouraging support for the most vulnerable populations. Over time, though, worldwide data is showing that women and men are getting infected with COVID-19 at near equal rates. Stereotypes regarding the types of occupations and tasks taken on by women did not hold water once the statistics were known. In fact, men are more likely to die from a COVID-19 infection than women.

Figure 7.10 Number of Global COVID-19 Deaths Where Sex is Known, as of 2021. Men die more frequently.

The Sex, Gender, and COVID-19 Project works to collect all kinds of COVID-19 numbers, and dis-aggregate, or separate, the statistics by male, female or non-binary gender. In the chart in figure 7.10, the chart demonstrates that more men are dying from COVID-19 than women.

To understand why this is so, the social scientists from this project highlight both biological sex characteristics and socially constructed gender. They note that men have higher levels of an enzyme called ACE2. This enzyme allows viruses to enter cells more easily, which might tend to make men sicker than women. In addition to biological differences, the evidence highlights differences in behavior and in social structures. In general, men tend to engage in more risky health behaviors such as drinking and smoking. These behaviors lead to poorer overall health and more risk of early death. Also, men tend to seek treatment later than women. The scientists write:

However, experience and evidence thus far tell us that both sex and gender are important drivers of risk and response to infection and disease. For example, even in the case of ACE2 (the enzyme that helps the virus enter the body’s cells), there are generally more ACE2 receptors in the heart cells of someone with pre-existing heart disease. And heart disease itself is associated with gender. In many societies today it is men who are more likely to suffer from heart disease and chronic lung disease as they are more frequently smokers, drinkers or working in occupations that expose them to risk of air pollution.

Other gender-based drivers of inequality may include men’s generally lower use of health services, including preventive health services – which might mean that men are further along in their illness before they seek care, for example. In the case of ebola, men typically presented at hospital 12 hours later in the course of the disease than women did – and men’s death rate was higher. (Donnelly et al. 2016)

We are reacting to the COVID-19 pandemic and trying to understand complex links between the causes of pandemic sickness and death at the same time, so our scientific conclusions may change as we learn more. Even if the final analysis changes, gender is one dimension of difference that helps to explain unequal health outcomes during COVID-19.

Gender is also a key variable in understanding health with a wider lens. Women are affected adversely both by unequal access to and institutionalized sexism in the healthcare industry. According to a recent report from the Kaiser Family Foundation, women experienced a decline in their ability to see needed specialists between 2001 and 2008. In 2008, one-quarter of women questioned the quality of their healthcare (Ranji & Salganico 2011). Quality is partially indicated by access and cost. In 2018, roughly one in four (26 percent) women—compared to one in five (19 percent) men—reported delaying healthcare or letting conditions go untreated due to cost. Because of costs, approximately one in five women postponed preventive care, skipped a recommended test or treatment, or reduced their use of medication due to cost (Kaiser Family Foundation 2018).

We can see an example of institutionalized sexism in the way that women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with certain kinds of mental disorders. Psychologist Dana Becker notes that 75 percent of all diagnoses of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) are for women according to the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. This diagnosis is characterized by instability of identity, of mood, and of behavior, and Becker argues that it has been used as a catch-all diagnosis for too many women. She further explains the stigma of the diagnosis, saying that it predisposes many people, both within and outside of the profession of psychotherapy, against women who have been so diagnosed (Becker n.d.).

Many critics also point to the medicalization of women’s issues as an example of institutionalized sexism. Medicalization refers to the process by which previously normal aspects of life are redefined as deviant and needing medical attention to remedy. Historically and contemporaneously, many aspects of women’s lives have been medicalized, including menstruation, premenstrual syndrome, pregnancy, childbirth, and menopause. The medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth has been particularly contentious in recent decades, with many women opting against the medical process and choosing natural childbirth. Fox and Worts (1999) find that all women experience pain and anxiety during the birth process, but that social support relieves both as effectively as medical support. In other words, medical interventions are no more effective than social ones at helping with the difficulties of pain and childbirth. Fox and Worts further found that women with supportive partners ended up with less medical intervention and fewer cases of postpartum depression. Of course, access to quality birth care outside the standard medical models may not be readily available to women of all social classes.

7.3.5 Health Inequalities by Gender Identity

Gender identity and sexual orientation may also impact how a person experiences health and illness. However, understanding these unequal experiences based on sociological data is challenging. Because it has been illegal to be queer or transgender until recently in the United States, many people do not disclose their unique identities. The agencies that collect data about gender identity and sexual orientation have only recently begun to re-tool their data collection methods so that people can report their gender identity or sexual orientation. Despite these limitations, though, we notice inequality.

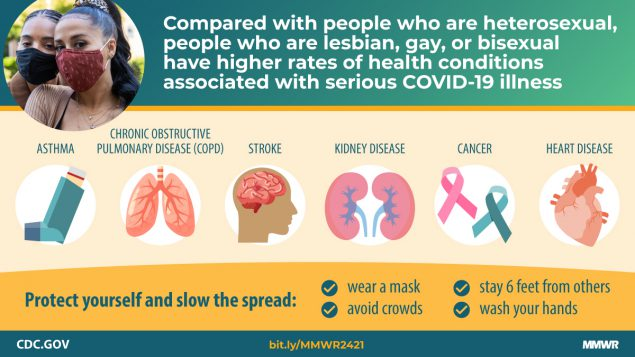

For example, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) examined risk factors for COVID-19 illness or death, they found that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people had challenging underlying health conditions more often than straight people (figure 7.11). The report points primarily to economic causes as a core cause of the difference, indicating that lesbian, gay, and bisexual people, particularly if they are Black or Brown, experience less economic stability (Heslin & Hall 2021).

Figure 7.11 CDC Infographic COVID and LGBTQIA+ health (Heslin & Hall 2021). Figure 7/11 Image Description

When examining the overall health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, the American College of Physicians finds similar issues. They also highlight the connections between laws, discrimination, and rejection that result in poorer health outcomes for LGBTQIA+ people:

These laws and policies, along with others that reinforce marginalization, discrimination, social stigma, or rejection of LGBT persons by their families or communities or that simply keep LGBT persons from accessing health care, have been associated with increased rates of anxiety, suicide, and substance or alcohol abuse. (Daniel 2015)

Transgender people have unique health concerns that are rarely addressed well by current practices. Although transgender people differ in their desires regarding medical support for their physical transitions, many of the procedures are not covered by insurance. When examining health outcomes for transgender people, the report states:

Transgender persons are also at a higher lifetime risk for suicide attempt and show higher incidence of social stressors, such as violence, discrimination, or childhood abuse, than nontransgender persons. A 2011 survey of transgender or gender-nonconforming persons found that 41 [percent] reported having attempted suicide, with the highest rates among those who faced job loss, harassment, poverty, and physical or sexual assault. (Daniel 2015)

In this episode of All Things Considered: Heath Care System Fails Many Transgender Americans, the journalist notes that simple things, like having forms that indicate only male and female, become barriers to accessing health care services. Transgender people are more likely to experience health conditions that are preventable because it is difficult to find medical providers that will treat them with respect. The videos that are linked to this episode explore issues related to transgender health in more detail.

Perhaps this doesn’t need to be said, but it is not the gender identity or sexual orientation per se that causes poorer health outcomes. Instead, it is the social structure embedded with stigma, discrimination, and violence that makes life riskier and shorter for LGBTQIA+ people.

7.3.6 Health and Disability

Figure 7.12 The handicapped accessible sign indicates that people with disabilities can access the facility. The Americans with Disabilities Act requires that access be provided to everyone.

Disability refers to a reduction in one’s ability to perform everyday tasks. The World Health Organization makes a distinction between the various terms used to describe handicaps that are important to the sociological perspective. They use the term impairment to describe the physical limitations a person may face, while reserving the term disability to refer to the social limitations, such as the fact that people with disabilities are far less likely to be employed than people without disabilities.

Before the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990, people in the United States with disabilities were often excluded from opportunities and social institutions many of us take for granted. This occurred not only through employment and other kinds of discrimination but also through casual acceptance by most people in the United States of a world designed for the convenience of the able-bodied. Imagine being in a wheelchair and trying to use a sidewalk without the benefit of wheelchair-accessible curbs. Imagine a blind person trying to access information without the widespread availability of Braille. Imagine having limited motor control and being faced with a difficult-to-grasp round door handle. Issues like these are what the ADA tries to address. Ramps on sidewalks, Braille instructions, and more accessible door levers are all accommodations to help people with disabilities.

People with disabilities can be stigmatized by their illnesses. The sociological concept of stigma can be applied widely to people who are marginalized because of poverty, race, citizenship status, and other factors. Stigmatization means their identity is spoiled; they are labeled as different, discriminated against, and sometimes even shunned. Erving Goffman, who is the mid-century sociologist who pioneered stigma theory, used the words “spoiled identity” to refer to stigmas, however, this language is not commonly used by sociologists to describe stigma today, as it in itself can be stigmatizing. People with disabilities may be labeled (as an interactionist might point out) and ascribed a master status (as a functionalist might note), becoming the blind girl or the boy in the wheelchair instead of someone afforded a full identity by society. This can be especially true for people who are disabled due to mental illness or disorders.

Many mental health disorders can be debilitating and can affect a person’s ability to cope with everyday life. This can affect social status, housing, and especially employment. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2011), people with a disability had a higher rate of unemployment than people without a disability in 2010. This unemployment rate refers only to people actively looking for a job. In fact, eight out of ten people with a disability are considered “out of the labor force;” that is, they do not have jobs and are not looking for them. The combination of this population and the high unemployment rate leads to an employment-population ratio of 18.6 percent among those with disabilities. The employment-population ratio for people without disabilities was much higher, at 63.5 percent (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2011).

7.3.7 Licenses and Attributions for Epidemiology in the U.S.: Health Disparities by Social Location

“Social Determinants of Health” by Kim Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.6 Social Determinants of Health Model: Source: Center for Disease Control (CDC). Public Domain

Figure 7.7 Trauma and Social Location ACEs_social-location_2015.pdf

“Epidemiology in the U.S.: Health Disparities by Social Location ” by Kate Burrows and Kim Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

19.3 Heath in the United States CC-BY 4.0 Added additional details related to infant mortality rates, COVID-19 and outcomes for LGBTQIA+ populations.

Figure 7.8 Infant Mortality by Race and Ethnicity, 2018 https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/infantmortality.htm

Figure 7.9 and related text on COVID-19 and Gender: The Sex, Gender and COVID-19 Project https://globalhealth5050.org/the-sex-gender-and-covid-19-project/men-sex-gender-and-covid-19/ CC-BY Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

Figure 7.10 Number of Global COVID-19 Deaths Where Sex is Know. ( https://globalhealth5050.org/wp-content/uploads/November-2021-data-tracker-update.pdf Nov 2021) CC-BY Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

Figure 7.11 CDC Infographic COVID and LGBTQ health (Heslin & Hall, 2021)

Figure 7.12 The handicapped accessible sign indicates that people with disabilities can access the facility. The Americans with Disabilities Act requires that access be provided to everyone. (Credit: Ltljltlj/Wikimedia Commons)