7.4 Sociological Theories of Health

Like all social problems, the concepts of health and illness are socially constructed. The definition of the social construction of illness experience is based on the idea that there is no objective reality, only our own perceptions of reality. The theories surrounding the social construction of health emphasize the social and cultural aspects of the discipline’s approach to physical, objectively definable phenomena. This section examines a comprehensive framework that focuses on the cultural meaning of illness, the social construction of the illness experience, and the social construction of medical knowledge (Conrad & Becker, 2010).

7.4.1 The Cultural Meaning of Illness

Most medical sociologists contend that illnesses have both a biological and an experiential component and that these components exist independently of each other. Our culture influences the way we experience illness, dictating which illnesses are stigmatized, which are considered disabilities or impairments, and which are contestable as opposed to definitive (Conrad & Barker, 2010). Contested illnesses are those that are questioned or questionable by some medical professionals. Disorders like fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome are real physical experiences, but some medical professionals contest whether these ailments are definable in medical terms. This causes a problem for a patient with symptoms that might be explained by a contested illness – how to get the treatment and diagnosis they need in the face of a medical establishment that does not believe their symptoms are real.

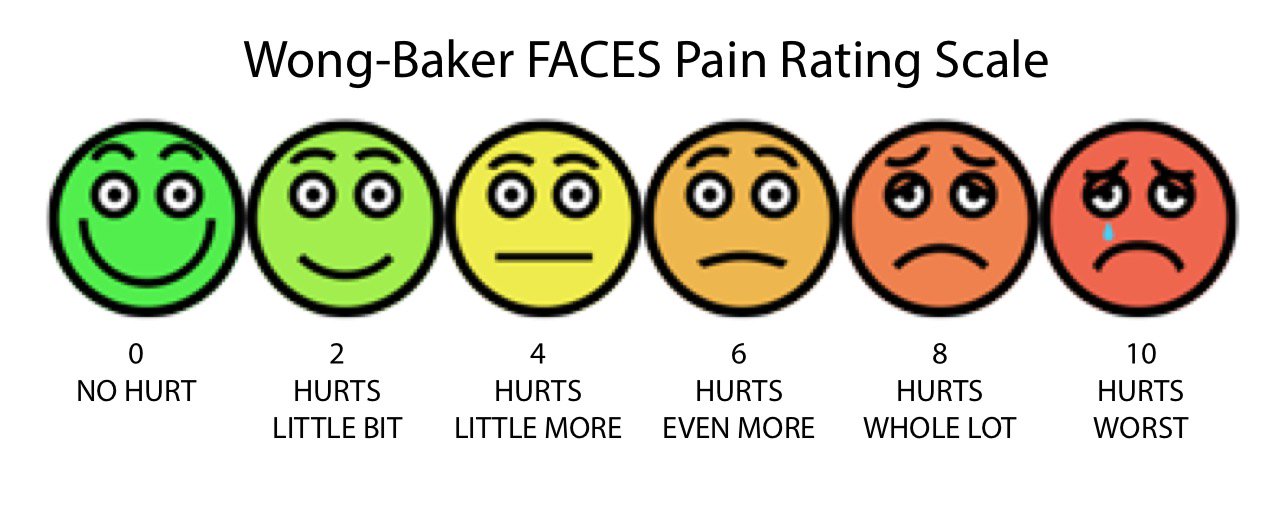

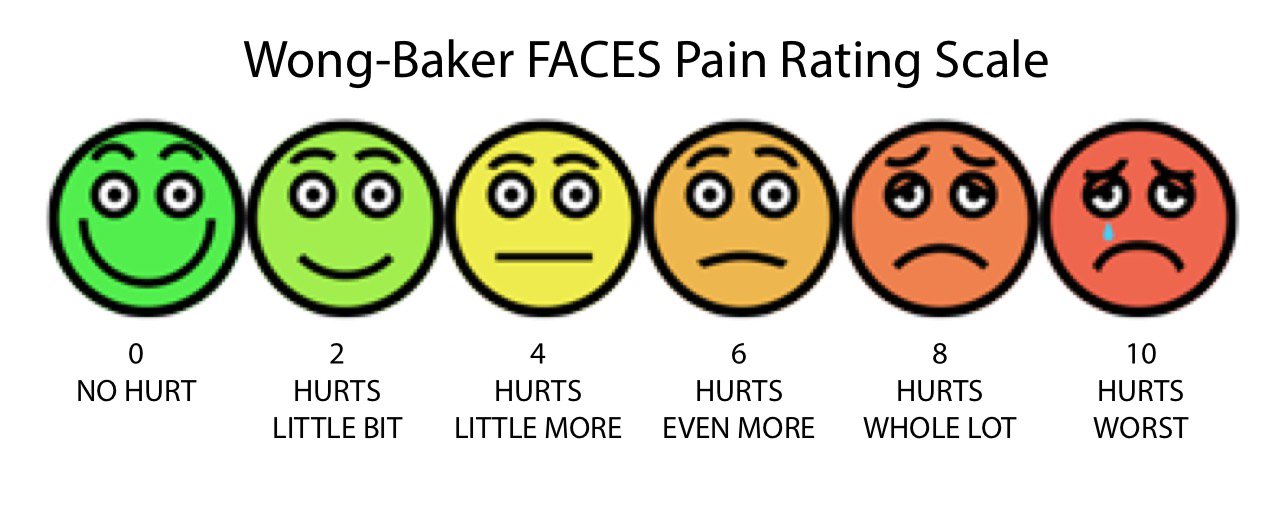

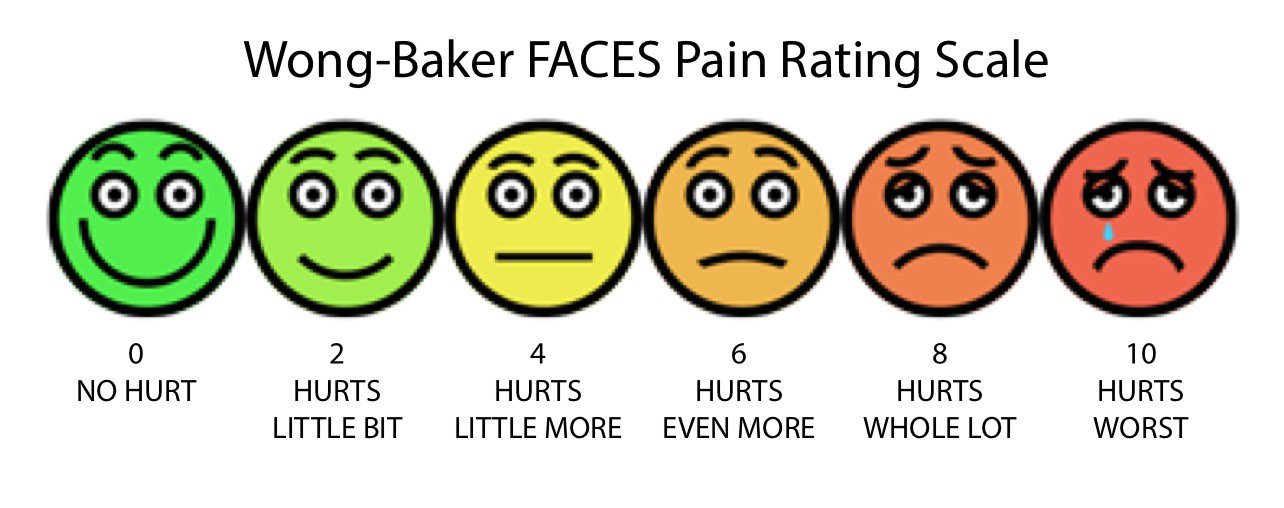

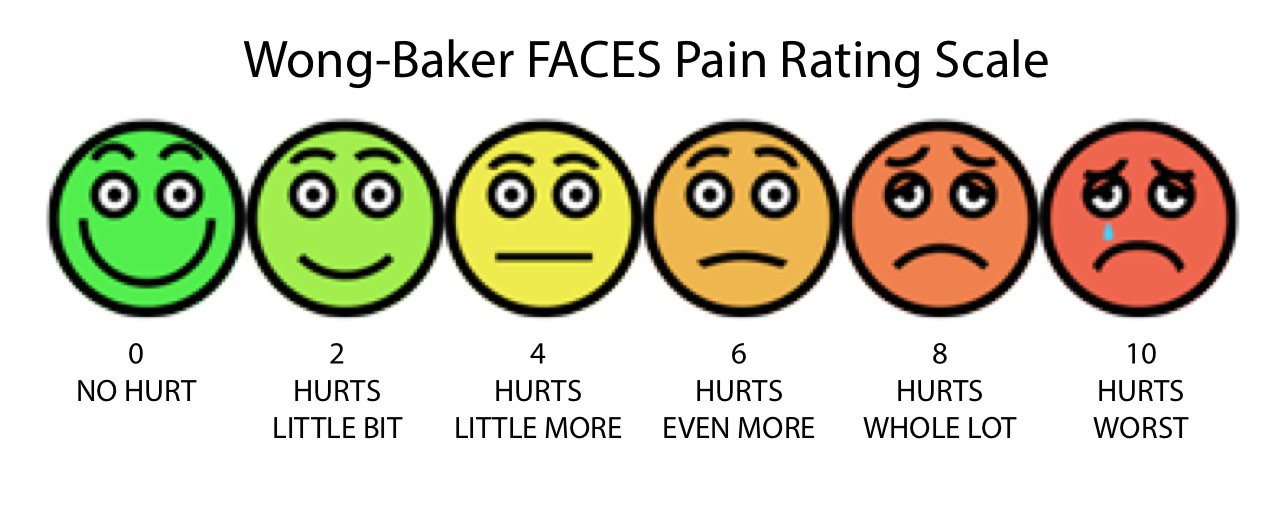

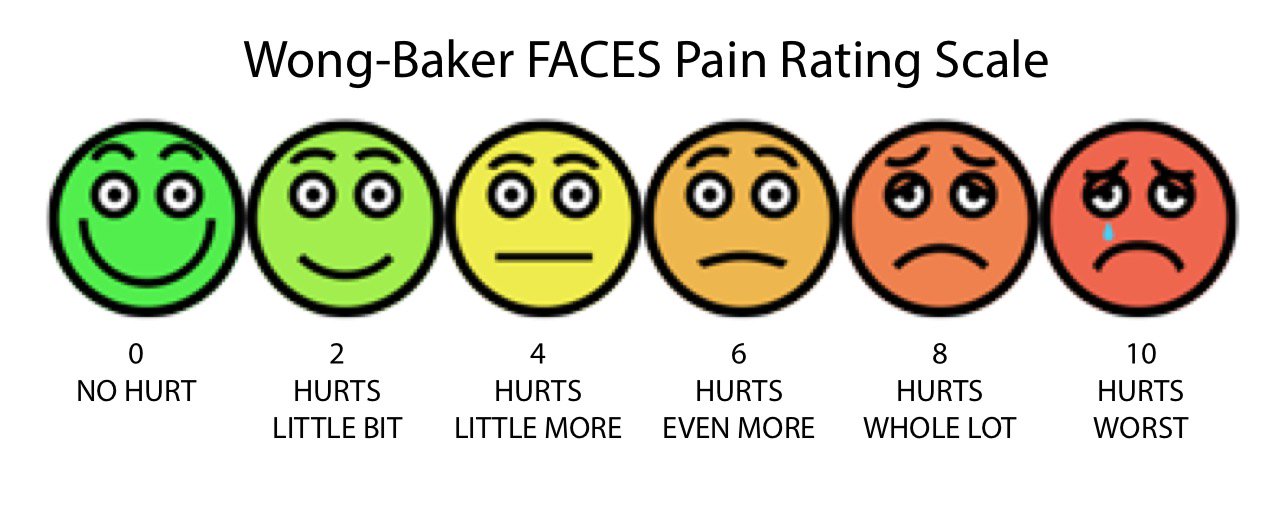

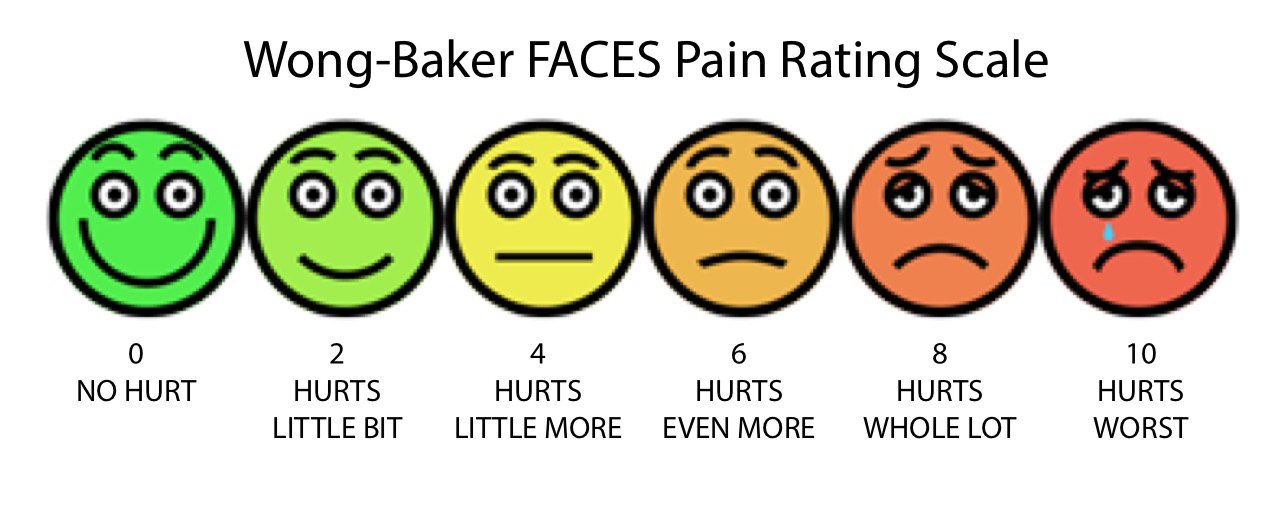

Individual and cultural perceptions of exertion and pain can make it difficult for healthcare workers to treat illnesses since they cannot be measured using a device. Instead, assessment tools like the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) Scale attempt to measure exertion at the individual level using accessible language and visual cues. This RPE chart includes the Wong-Baker FACES pain assessment tool, which is used often in healthcare settings because it works for a variety of ages, ability levels, and can be understood by those whose primary language is not English. This Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) gives a more complete view of an individual’s actual exertion level, since heart rate or pulse measurements may be affected by medication or other issues (Centers for Disease Control 2011a).

|

Rating of Perceived Exertion |

|||

|

|

0 – Very light activity |

Minimal exertion, but more than sleeping or stationary activity. |

Heart rate, breathing, and physical comfort level are baseline. |

|

|

2 – Light activity |

Feels like you can maintain the activity for several hours. |

Breathing is normal. Heart rate higher than baseline. |

|

|

4 – Moderate activity |

Feel comfortable, but cannot maintain the activity for more than two hours. |

Can speak a few minutes before getting winded. Heart rate is elevated. |

|

|

6 – Vigorous activity |

Feel uncomfortable with multiple physical signs that your body is working hard. |

Can speak a sentence before becoming winded. Heart rate is elevated. |

|

|

8 – Very hard activity |

Difficult to maintain activity intensity for more than a few minutes. |

Can speak a few words before becoming winded. Heart rate is high. |

|

|

10 – Maximum effort activity |

Feels impossible to maintain activity intensity for more than a few minutes. |

Completely out of breath, unable to talk. Heart rate is very high. |

Figure 7.13: Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) Scale combined with the Wong-Baker FACES pain assessment tool.

7.4.2 Sick role and functionalist perspective

Health is vital to the stability of the society, so illness is often seen as a form of deviance. Talcott Parsons (1951), an American sociologist who was the first to systematize the study of social systems, and is considered one of the fathers of American mid-century sociology, was the first to discuss this in terms of the sick role: patterns of expectations that define appropriate behavior for the sick and those who take care of them. Having a physician certify that the illness is genuine is an important symbolic step in taking on the sick role. It also reveals the strong power and authority differential between the patient and physicians. An example of the power differential between a patient and the physician is if a physician calls the patient on the phone and leaves a voice message, the social norm and expectation is that the patient will call the physician back as soon as possible. However, if the patient calls the physician, the expectation is that it may take several days, or even a week, for the call to be returned. In this example, the physician’s priorities are different from that of the patient’s, and the patient has more social expectations to do what the physician says, and the physician has fewer social norms compelling them to respond to the patient. A long-term illness can have the effect of making our world seem smaller, more defined by the illness than anything else. An illness can be a chance for discovery, for re-imaging a new self (Conrad & Barker, 2007). Today, many institutions of wellness acknowledge the degree to which social location influences our personal understanding of health and wellness.

7.4.3 Social disparities and the conflict perspective

People with money and power, seen as the dominant group, are the ones who make decisions about how the healthcare system runs. They, therefore, ensure that they will have healthcare coverage, while simultaneously ensuring that subordinate groups stay subordinate through lack of access. This creates significant healthcare and health disparities between the dominant and subordinate groups. These ideas come straight from the conflict perspective that we’ve discussed in earlier chapters, which emphasizes that social class difference is the main cause of unequal outcomes, including health outcomes. Healthcare institutions include thousands of doctors, staff, patients, and administrators. They are highly bureaucratic but often struggle to serve all members of society equally due to racism, sexism, ageism, and heterosexism. When health is a commodity, the poor are more likely to experience illness caused by poor diet, living and working in unhealthy environments, and are less likely to challenge the system.

7.4.4 Medicalization and the symbolic perspective

The term medicalization of deviance refers to the process that changes bad behavior into sick behavior. A related process is demedicalization, in which sick behavior is normalized again. Both of these concepts come from the symbolic perspective of sociology, which asserts that society is created by repeated interactions between individuals and groups. Medicalization and demedicalization affect who responds to the patient, how people respond to the patient, and how people view the personal responsibility of the patient (Conrad & Schneider 1992). So far in this chapter, we have discussed medicalization as the process in which situations and behaviors are considered medical problems, rather than social problems. In the case of the medicalization of deviance, the social problems that may be medicalized are deviant behaviors. An example of this is the medicalization of Intermittent Explosive Disorder, which is a disorder listed in the DSM-5 as a psychiatric condition, but before its listing in the DSM in 1980, people who had emotionally explosive or aggressive behavior were considered deviant, but not sick. The medicalization of deviance in this case shows how what was previously considered deviant is now considered a medical problem.

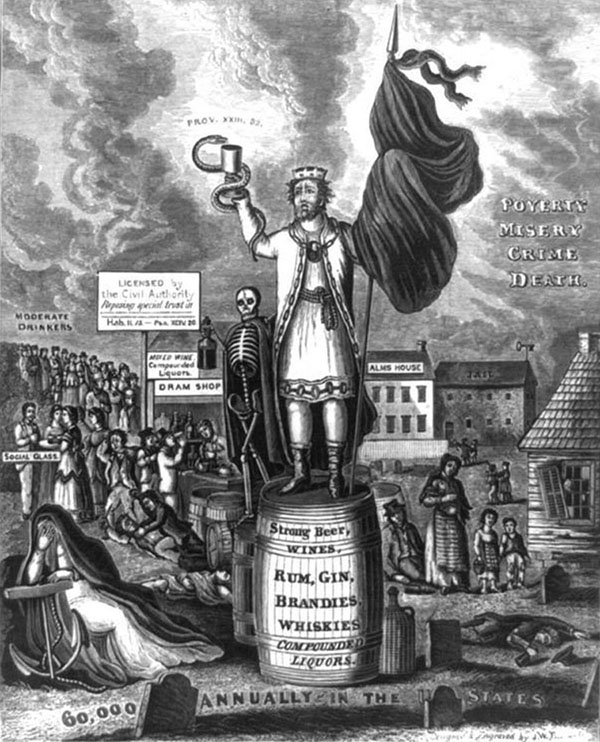

Figure 7.14 “King Alcohol” engraving from the 1800s. The words “poverty,” “misery,” “crime,” and “death” hang in the air behind him.

An example of medicalization is illustrated by the history of how our society views alcohol and alcoholism. During the nineteenth century, people who drank too much were considered bad, lazy people. They were called drunks, and it was not uncommon for them to be arrested or run out of a town. Drunks were not treated sympathetically because, at that time, it was thought that it was their own fault that they could not stop drinking. During the latter half of the twentieth-century, however, people who drank too much were increasingly defined as alcoholics: people with a disease or a genetic predisposition to addiction who were not responsible for their drinking. With alcoholism defined as a disease and not a personal choice, alcoholics came to be viewed with more compassion and understanding. Thus, badness was transformed into sickness.

Another important example of medicalization is the significant differences in who delivers babies worldwide. In Great Britain, midwives deliver half of all babies, including Kate Middleton’s first two children, Prince George and Princess Charlotte. In Sweden, Norway, and France, midwives oversee most expectant and new mothers, enabling obstetricians to concentrate on high-risk births. In Canada and New Zealand, midwives are so highly valued that they’re brought in to manage complex cases that need special attention. The medicalization of childbirth in the U.S. is so pervasive, that most expectant mothers in the U.S. give birth in hospitals, with fetal monitors, medications, and other medical interventions that are simply unnecessary for the majority of healthy pregnancies. In fact, severe maternal complications in the U.S. have more than doubled in the last 20 years.

Shortages of maternity care have reached critical levels, with nearly half of U.S. counties without a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist. In rural areas, the number of hospitals offering obstetric services has fallen more than 16 percent since 2004. Midwives are far less prevalent in the U.S. than in other affluent countries, attending around 10 percent of births, and the extent to which they can legally participate in patient care varies widely from one state to the next. At times the cultural stigmas regarding medical practices can cause people to seek medical services that don’t meet their needs. There are other aspects of the U.S. healthcare system that rise as important social problems to be addressed.

7.4.5 Indigenous and First Nations Understanding of Health

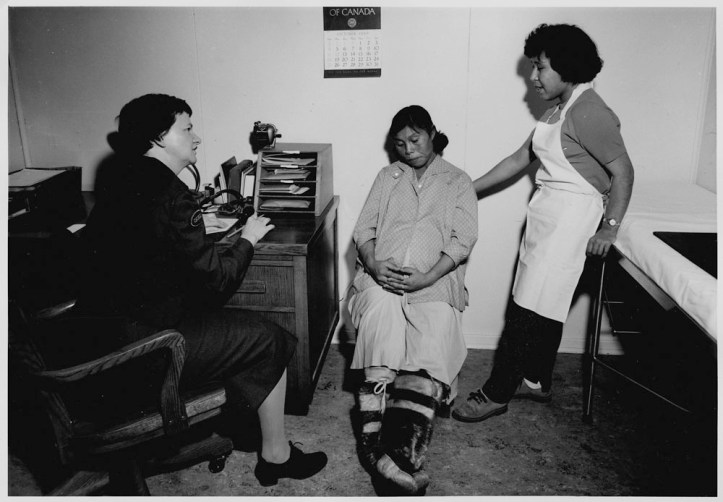

Figure 7.15 An Indigenous woman receives healthcare in the 1920s.

Like feminist sociologists, scholars studying the health of Indigenous people provide competing values, claims, and outcomes related to the social problem of health. In exploring this history, we examine the history of Indigenous nursing in Canada. Several stories coincide: stories about education, colonialism in health care, Indigenous women and work, and racism in the nursing profession, for example. But one starting point is the founding of the Registered Nurses of Canadian Indian Ancestry (RNCIA) in the mid-1970s, an important professional and political organization for Indigenous nurses in Canada.

Most of the original goals of the RNCIA had to do with moving into a central position within the federal Indian health system and extending Indigenous people’s self-advocacy and authority. RNCIA nurses also sought to re-write the standard curriculum in Canadian nursing schools and insisted on Indigenous representation in workplaces serving Indigenous people. Their objectives were practical and reasonable: to improve Indigenous health by fostering education, data collection, and Indigenous nurse participation in health care programming and provision.

But in the historical context of both the twentieth century Indian health system in Canada and inequity in the health status of Indigenous people, these goals were, in fact, revolutionary. The RNCIA wanted to transform the very nature of the relationships between Indigenous people and governments and reject the colonization of Indigenous health.

Figure 7.16 Jean Goodwill, Founder, Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association. (© C.I.N.A.)

Let’s take a look at one of the RNCIA’s objectives to see what we can learn about Indigenous nursing history: It reads that the RNCIA aimed, “To act as an agent in promoting and striving for better health for the Indian people, that is, a state of complete physical, mental, social, and spiritual well-being.” (McCallum 2017)

This goal is significant for a number of reasons. The RNCIA was the first group of Indigenous professionals in Canada to organize as an association. Most professional associations form in order to improve wages and working conditions. Instead, the RNCIA spoke about the health of Indigenous people and their goal to help to improve it.

This objective, moreover, was about action on the part of Indigenous nurses—“promoting and striving for better health.” Putting Indigenous nurses and their work at the core of the analysis is key to writing this history.

Third, this objective insisted upon a definition of health that suited Indigenous epistemologies and defined health as a state of complete physical, mental, social and spiritual well-being. As such, it also spoke to a different approach to or ethic of nursing.

Figure 7.17 Two Aboriginal nursing students and a nurse examine a medical mannequin.

This objective also addresses the historical conditions of colonization. Indigenous standards of health fell enormously during and after contact. The appropriation of land and resources, successive military and cultural invasions, as well as policies that served to weaken Indigenous people, communities, and nations, all resulted in widespread poverty and dislocation. These conditions not only fostered ill health and the suppression of Indigenous medicine, but also a health care system that did not by and large serve Indigenous people very well.

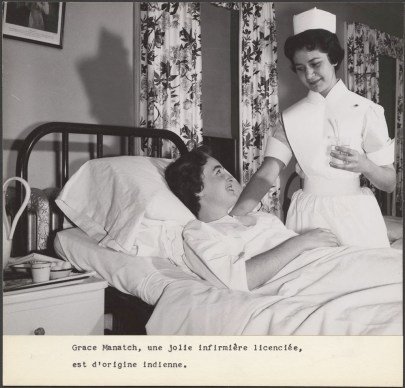

Figure 7.18 Indigenous nurse Grace Manatch sees a patient.

The existence of a critically engaged Indigenous nursing workforce has resulted in not only a professional challenge to inherent inequities in healthcare but also to some of the most vehement and longstanding stereotypes about Indigenous people. In addition, Indigenous nurse history forces a discussion of the colonial nature of the health system in Canada. Many Indigenous nurses worked within the limited, hierarchical, and non-local medical and nursing services run from the nation’s capital as a moral obligation rather than as a treaty responsibility.

Finally, one of the great contributions of Indigenous nursing history is that it puts Indigenous displacement and resistance at the center, rather than the periphery of, national history and the history of state formation. Critically, this centers racism and inequality in discussions of federal education, health and employment policy. For example, many Indigenous nurses in Canada had a compromised educational background at segregated federal Indian schools, be they residential or day schools. Until after the 1940s, they faced color bars at Canadian nursing schools, as well as a number of other substantial barriers long after. In employment, Indigenous nurses faced assumptions about their abilities and their competence as Indigenous nurses. Any successes were attributed to assimilation. The persistence of Indigenous expertise in nursing in spite of this is inspiring.

7.4.6 Licenses and Attributions for Sociological Theories of Health

“Sociological Theories of Health ” by Kate Burrows is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adapted from19.1 The social construction of health and 19.5 Theoretical Perspectives on Health and Medicine CC-BY 4.0 added content related to Indigenous Nursing

Figure 7.13 “Rating of Perceived Exertion” by Kaitlin Hakanson (2022) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Sources: Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale, Twitter post by Haydn Drake @paramedickiwi; Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale, CDC.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/measuring/exertion.htm

Figure 7.14 In this engraving from the nineteenth century, “King Alcohol” is shown with a skeleton on a barrel of alcohol. The words “poverty,” “misery,” “crime,” and “death” hang in the air behind him. (Credit: Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons)

Section 7.4.9 Indigenous Nursing and the related figures 7.15, 7.16, 7.17

The How and Why of Indigenous Nursing https://nursingclio.org/2017/11/30/the-how-and-why-of-indigenous-nurse-history/ Added social problem language Creative Commons BY-NC-SA

Figure 7.15 An Indigenous woman receives healthcare in the 1920s

Figure 7.16 Jean Goodwill, Founder, Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association. (© C.I.N.A.)

Figure 7.17 Two Aboriginal nursing students and a nurse examine a medical mannequin. (Canadian National Archives)

Figure 7.18 Indigenous nurse Grace Manatch sees a patient. (Canadian National Archives)