8.4 Four Models of Addiction

In this section, we explain the four basic models of addiction that are dominant in U.S. society: the moral view, the disease model, a sociological approach, and a public health perspective. We will discuss these four views or models in this section, as well as where these models can be found in action within society.

8.4.1 Moral View

The moral view depicts the use of illicit substances and the state of addiction as wrong or bad. Illicit drug use is understood as a sin or personal failing. Faith-based drug rehabilitation programs are one location where we see the moral model in use. Through qualitative interviews with individuals who had attended such a facility, Gowan and Atmore (2012) found that within the teachings of evangelical conversion-based rehab, substance use is thought to be rooted in immorality. This requires the user to convert and submit to religious authority to recover. Gowan and Atmore (2012) found that the program implied that the root of addiction was in secular, or nonreligious, life. The rigid structure of faith-based drug treatment programs can be helpful for some in recovery.

|

Schedule |

Definition |

Examples |

|

Schedule I |

No currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. |

Heroin, LSD, and marijuana |

|

Schedule II |

High potential for abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence. These drugs are also considered dangerous. |

Vicodin, cocaine, methamphetamine, methadone, hydromorphone (Dilaudid), meperidine (Demerol), oxycodone (OxyContin), fentanyl, Dexedrine, Adderall, and Ritalin |

|

Schedule III |

Moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence. Abuse potential is less than Schedule I and Schedule II drugs but more than Schedule IV. |

Tylenol with codeine, ketamine, anabolic steroids, testosterone |

|

Schedule IV |

Low potential for abuse and low risk of dependence. |

Xanax, Soma, Valium, Ativan, Talwin, Ambien, Tramadol |

|

Schedule V |

Lower potential for abuse than Schedule IV and consist of preparations containing limited quantities of certain narcotics. Generally used for antidiarrheal, antitussive, and analgesic purposes. |

Robitussin AC with codeine, Lomotil, Lyrica |

Figure 8.6 Drug Schedule

The moral view toward drug use can also be seen in our criminal justice system and the criminalization of drug use. Criminalization is the act of making something illegal. The 1970 Comprehensive Drug Abuse and Control Act (US House 1970) created drug categorizations, called schedules, based on the drug’s potential for abuse and dependency and its accepted medical use. This new system of categorization acknowledged the medical use of some drugs while heightening the criminalization of other drugs (figure 8.6). Drug policy in the United States is guided by the moral view of drug use. It calls for those who use substances to be punished whether it is through fines, some form of home arrest, or incarceration.

8.4.2 Disease Model

8.7 The Drunkard’s Progress, an 1864 lithograph by Nathanial Currier shows the progression of alcoholism as a disease. By organizing the information into careful steps, the illustrator uses the trappings of science to popularize the disease model.

Understanding drug use and particularly addiction to mind-altering substances as a disease is another dominant model found within U.S. society and its social institutions. The idea of considering substance use a disease is at least 200 years old. Researching the history of the disease concept of addiction, sociologist Harry Levine (1978) found that habitual drinking during the eighteenth century was not considered a problematic behavior. The emergence of the temperance movement in the nineteenth century shifted American thought toward understanding addiction as a progressive disease. With this disease, a person lost their will to control the consumption of a substance. In the 1940s the National Council of Alcoholism was founded by E.M. Jellinek, a professor of applied physiology at Yale. The purpose of this council was to popularize the disease model of addiction by putting it on scientific footing by conducting research studies on drug use. This history shows us that science was not the source of the disease model but, rather, a resource for promoting it (Reinarman 2005).

The disease model of addiction also involves the use of pharmaceuticals, such as methadone, to treat physical and psychological dependence on opiates. Physicians Vincent Dole and Marie Nyswander successfully researched the use of methadone to stabilize a group of 22 patients previously addicted to heroin. Dole and Nyswander (1965) found that with the medication and a comprehensive program of rehabilitation the patients showed marked improvements. They returned to school, obtained jobs, and reconnected with their families. The researchers found that the medication produced no euphoria or sedation and removed opiate withdrawal symptoms.

The legitimacy of the disease model of addiction was reinforced by the clinical research findings of Dole and Nyswander, which showed that a pharmaceutical (i.e., methadone) could be used to treat addiction. Dole and Nyswander (1965) wrote: “Maintenance of patients with methadone is no more difficult than maintaining diabetics with oral hypoglycemic agents, and in both cases the patient should be able to live a normal life.” Those who support the disease model of addiction often compare addiction to diabetes. The analogy demonstrates the similarity of addiction to other diseases.

Since the 1990s addiction has been understood as a neurobiological disease and referred to as a chronic relapsing brain disease (or disorder). Using brain imaging technology, scientists and researchers came to find that addictive long-term use of substances changed the structure and function of the brain and had long-lasting neurological and biological effects.

Social scientists have questioned the sole use of the disease model to understand addiction, asserting that addiction also involves a social component. They point out that the disease of addiction is not diagnosed through brain scans. Rather, it is often identified when one is breaking cultural and social norms around productivity and compulsion (Kaye 2012).

8.4.3 Public Health Perspective

A public health perspective toward substance use incorporates a sociological understanding of drug use but focuses on maintaining the health of people who use drugs. Often this approach is labeled harm reduction and focuses on providing people who use drugs with the information and material tools to reduce their risks while using drugs. This perspective focuses on reducing the harm of substance use rather than requiring abstinence from all drug use. Similar harm reduction strategies are wearing seat belts or providing adolescents with condoms.

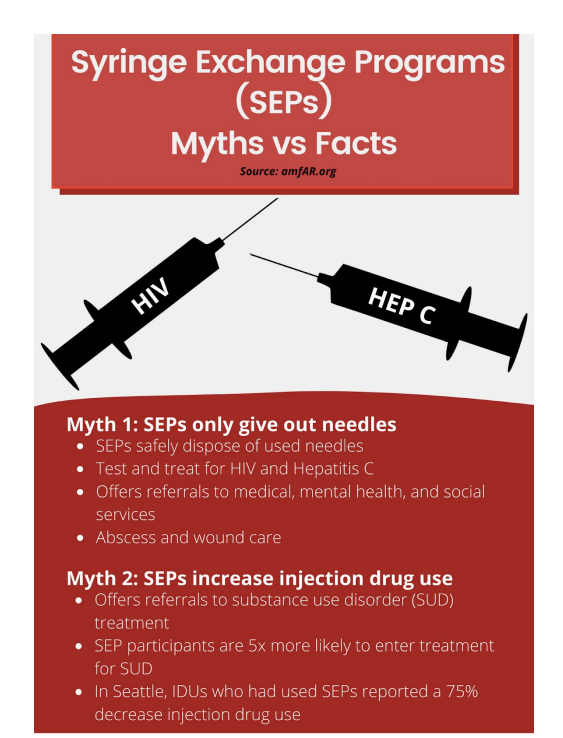

Figure 8.8 Myths and Facts in Syringe Exchange Programs – Syringe Exchange Programs reduce harm.

One of the most well-known harm reduction practices is syringe exchange. This became legal during the HIV epidemic of the 1980s and ’90s to help people who inject drugs avoid infection with the then-deadly virus. Currently, harm reduction is also associated with the distribution of the opioid overdose reversal antidote—Narcan or naloxone. This harmless medication can almost instantaneously reverse an opioid overdose, saving a person’s life.

The public health or harm-reduction perspective toward drug use can be controversial because some believe that it enables drug use. There is no scientific evidence to support this idea. Contrary to this assertion, scientific evidence shows that syringe exchange reduces HIV and hepatitis C rates and the distribution of Narcan lowers drug overdose mortality rates (Platt et al. 2017; Fernandes et al. 2017; Chimbar & Moleta 2018).

8.4.4 Sociological Model

The sociological model of drug use and addiction examines how social structures, institutions, and phenomena may lead individuals to use mind-altering substances to cope with difficulty and distress. A sociological view also examines how social inequalities can make the impacts of drug use worse for some social groups than others.

Within the sociological model, a sociopharmacological approach looks at how social, economic, and health policy might exacerbate harm to people using substances. Sociopharmacology is a sociological theory of drug use developed by long-time drug use researcher Samuel R. Friedman. Friedman (2002) writes that approaches toward understanding drug use that focus on the psychological traits of the people using the drugs and the chemical traits of the drugs ignore socioeconomic and other social issues that make individuals, neighborhoods, and population groups vulnerable to harmful drug use.

To consider how the sociopharmacological approach plays out in everyday life, consider how drug policy prohibits the use of heroin and results in several harmful effects. New syringes can be hard to find. People will inject in unclean and rushed circumstances, which may negatively impact their health by putting them at risk for contracting HIV or life threatening bacterial infections.

This type of analysis is also thought of using the analytic concept of risk environments developed by Tim Rhodes. A risk environment is the social or physical space where a variety of things interact to increase the chances of drug-related harm. An analysis of risk environment looks at how the relationship between the individual and the environment impacts the production or reduction of drug harms (Rhodes 2002).

In his sociopharmacology theory, Friedman also notes that the social order might cause misery for some social groups which in turn might cause people to self-medicate with drugs. The pain of not being respected as a human being, which can result from the structure of the workplace and/or gender and racial subordination, may cause individuals to cope via drug use.

For example, working a low-paying service job where you deal with unhappy customers and mistreatment from your boss may lead you to blow off steam by using substances. Individualistic theories of drug use stigmatize and demonize individuals who use drugs as being weak or criminal. According to the sociopharmacological approach, if anything should be demonized, it should be the social order—not the individual who uses drugs (Friedman 2002).

Looking at the social determinants of the opioid crisis provides a way to discuss a sociological approach to studying drug use. Many approaches to understanding the opioid crisis focus on the supply of opioids in the U.S. and whether they were pharmaceutical or illicit. This approach misunderstands the reasons individuals used opioids. The label deaths of despair has been used to describe three types of mortality that are on the rise in the U.S. and have caused a decline in the average lifespan among Americans. These three deaths occur from drug overdose, alcohol-related disease, and suicide. Death from these conditions has risen sharply since 1999, especially among middle-aged White people without a college degree (Dasgupta et al. 2018).

Figure 8.9 “Deaths of despair” are surging in white America [YouTube Video]. Economists Anne Case and Sir Angnes Deaton explain their research on the opioid crisis and deaths of despair in this 3:47 minute video. As you watch, please pay attention to the social forces that influence this social problem.

Researchers are examining how the economic opportunities impact opioid use and overdose rates. In a study focused on the Midwest, Appalachia and New England, researchers found that mortality rates from deaths of despair increased as county economic distress worsened. In rural counties with higher overdose rates, economic struggle was found to be more associated with overdose than opioid supply (Monnat 2019).

Analysis of the social and economic determinants of the opioid crisis notes that the jobs available in poor communities, which are often in manufacturing or service, present physical hazards and cause long-term wear and tear on the worker’s body (Dasgupta et al. 2018). An on-the-job injury can lead to chronic pain, which may disable a person. The disability may cause them to seek pain relief through opioids. The resulting addiction pushes them into poverty and despair. The video in figure 8.9 describes the trends in the deaths of despair.

A 2017 report from the National Academy of Sciences used a sociological view of drug use when it commented on the cause of the opioid crisis. The report states:

Overprescribing was not the sole cause of the problem. While increased opioid prescribing for chronic pain has been a vector of the opioid epidemic, researchers agree that such structural factors as lack of economic opportunity, poor working conditions, and eroded social capital in depressed communities, accompanied by hopelessness and despair, are root causes of the misuse of opioids and other substances (Zoorob & Salemi 2017).

Higher levels of social capital within a community might protect it from higher overdose rates. Social capital is defined as the social networks or connections that an individual has available to them due to group membership. These researchers measured social capital by looking at voting rates, the number of non-profit and civic organizations in a community, and response rates to the census (Zoorob & Salemi 2017). These are all indicative of one’s engagement with their community, as well as increased social linkages between people through community organizations.

A sociological view of drug use helps us to understand the social contexts that can lead to drug use and cause it to be harmful or deadly. Without a sociological analysis, we’d only be looking at individual people and drugs and missing the entire social environment leading up to and occurring around drug use. A sociological analysis notices widespread social structural elements that might increase drug use (e.g., economic despair and hopelessness), which in turn can help us create policies and programs that can be beneficial for large numbers of people. Like other social problems, we see that differences in social location create unequal outcomes.

8.4.5 Licenses and Attributions for Four Models of Addiction

“Four Models of Addiction” by Kelly Szott is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.6 “Drug Schedule” in Legal Foundations and National Guidelines for Safe Medication Administration by Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN). License: CC-BY-4.0.

8.7 The Drunkard’s Progress Lithograph by Nathaniel Currier is in the Public Domain

8.8 “Syringe Exchange Programs” in https://www.amsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Syringe-Exchange-Toolkit-Draft.pdf Fair Use