9.2 The Basics: Mental Health and Mental Illness as a Social Problem

In our everyday lives, we might say that someone is crazy. Or we might say that we feel out of it. These terms are commonly used, but social scientists have to be much more precise in their language. This section explores what we really mean when we say mental health, mental illness and mental well-being.

Once we have defined our terms, we explore why mental health and mental illness are a social problem, not just an individual one.

9.2.1 What Do We Mean, Really?

In “Kate’s Story” that opens this chapter, the people used their diagnosis to sort people into groups. But what does that actually mean?

Mental health is a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, good behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life (American Psychological Association, n.d.). It includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel, and act. It also helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others, and make choices.

Mental health includes subjective well-being, autonomy, and competence. It is the ability to fulfill your intellectual and emotional potential. Mental health is how you enjoy life and create a balance between activities. Cultural differences, your own evaluation of yourself, and competing professional theories all affect how one defines mental health. Mental health is important at every stage of life, from childhood and adolescence through adulthood.

When sociologists study mental health, they look at trends across groups. They look at how mental health varies between all genders, different racial and ethnic groups, different age groups, and people with different life experiences, including socioeconomic status. In addition to this, though, they also explore the factors that maintain—or distract from—mental health, such as stress, resilience and coping factors, the social roles we hold, and the strength of our social networks as a source of support.

The term mental health doesn’t necessarily imply good or bad mental health. At some times in your life, you are going to feel really good and have good coping skills, strong social networks, a fulfilling career and personal and family life, and you will feel good about yourself. At other times in your life, things may not be going so well for you. You may have work or family conflicts, and you find yourself engaging in poor coping skills and not reaching out to your social network to get support. Both of these are examples of mental health. In the next section, we are going to explore the concept of mental illness, which, contrary to common belief, is not the opposite of mental health. Rather, it is one type of experience a person can have with their mental health.

Over the course of your life, if you experience mental health problems, your thinking, mood, and behavior could be affected. Some early signs related to mental health problems are sleep difficulties, lack of energy, and thinking of harming yourself or others. Many factors contribute to mental health problems, including:

- biological factors, such as genes or brain chemistry

- life experiences, such as trauma or abuse

- family history of mental health problems

All of us will experience mental health challenges throughout our lives—times when we’re not sleeping, eating, or socializing as well as we know we could be. We may have times when we feel mildly depressed for a matter of days, or just don’t feel like doing much. These experiences are common and do not mean you have a mental illness.

Mental illness, also called mental health disorders, refers to a wide range of mental health conditions, disorders that affect your mood, thinking, and behavior. Examples of mental illness include depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders, and addictive behaviors. (Mayo, n.d.)

Unlike mental health, mental illness has a very specific and technical definition. Psychiatrists, psychologists, and even your primary care doctor use a manual called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) which is essentially a listing of every recognized mental illness. The DSM lays out each condition—297 in the most recent iteration— that is recognized by professionals to be a mental illness.

Each mental illness listed in the DSM has a list of diagnostic criteria that a person must meet in order to be considered to have that particular mental illness. For example, to get an official diagnosis of major depressive disorder, a person must meet five out eight symptoms, such as severe fatigue, feeling hopeless or worthless, or much less interest in activities you used to enjoy, for at least two weeks to be considered clinically depressed.

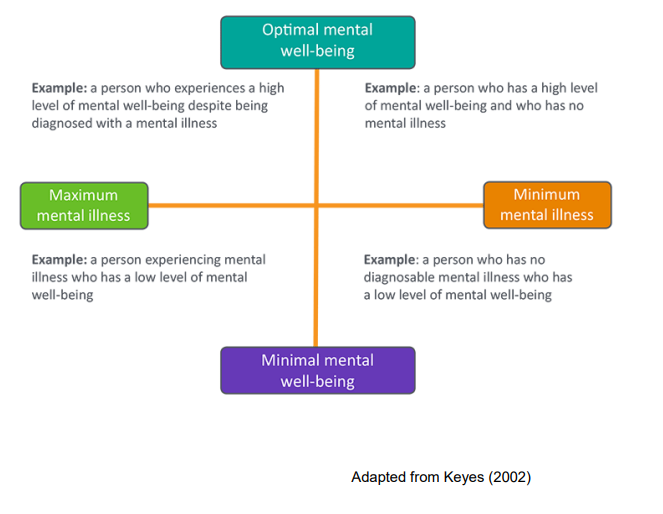

Figure 9.2 The Mental Health and Well-being Continuum. Have you ever considered that mental illness and mental well being might be different? Figure 9.2 Image Description

In addition to the definitions of mental health and mental illness that we commonly use to talk about diagnosis or lack of them, some people are starting to use the description of mental well-being. Mental well-being is an internal resource that helps us think, feel, connect, and function; it is an active process that helps us to build resilience, grow, and flourish (McGroarty 2021). While people can support their own mental well-being with long walks and hot baths, the core concept is more profound. It comprises the activities and attitudes that all of us can cultivate to ensure our own resilience, whether we have a mental health diagnosis or not. Mental well-being is a state that all of us can build or work on, so that we can respond effectively to the challenges of our lives.

The community activists and researchers who created the phrase mental well-being use it for two reasons. First, by separating a mental health diagnosis from the quality of mental well-being, we have a model that helps us understand that mental illness can be similar to a chronic disease. You can see this model for yourself in figure 9.2. Some days, or weeks, or years, the illness is very well managed, and the person leads a productive, happy, and fulfilling life. Other days, the illness is not well managed, and the person needs more support. On the other axis, some people may experience a life event that makes them deeply sad or feel powerless. They don’t have a mental health diagnosis, but they may need mental health treatment or support anyway. If seeing how the model works real time will help, please watch Mental Health Continuum [YouTube Video].

Second, some people and communities stigmatize both the people who have mental illnesses or need mental health treatment, and the words themselves. In those cases, using a word that doesn’t raise the barrier of stigma can allow new conversations to happen. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) hosts these two sites: Sharing Hope: Mental Wellness in the Black Community and Compartiendo Esperanza: Mental Wellness in the Latinx Community. Both sites have excellent videos that explore issues of mental wellness and resilience, mental health and mental illness for these specific communities.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness adds an additional perspective to the discussion by including a voice that had not been considered previously. This organization, a grassroots mental health organization evolved from a family discussion group into a nationwide organization of mental health providers and patients provided a voice of people with direct experience with mental health issues: patients experiencing direct impact of diagnosed and undiagnosed problems. This organization operates several public health and information projects relating to mental health and supervises efforts by the U.S. Congress to address mental health treatment and policy.

9.2.2 Why Is Mental Health and Mental Illness a Social Problem

In Chapter 1, we listed the characteristics of a social problem. If you will remember:

- A social problem goes beyond the experience of an individual.

- A social problem results from a conflict in values.

- A social problem arises when groups of people experience inequality.

- A social problem is socially constructed but real in its consequences.

- A social problem must be addressed interdependently, using both individual agency and collective action.

How might these apply to who feels OK?

9.2.2.1 Mental health and mental illness go beyond individual experience

Mental illnesses are common in the United States. Nearly one in five U.S. adults live with a mental illness (52.9 million in 2020). Mental illnesses include many different conditions that vary in degree of severity, ranging from mild to moderate to severe. Two broad categories can be used to describe these conditions: Any Mental Illness (AMI) and Serious Mental Illness (SMI). AMI encompasses all recognized mental illnesses. SMI is a smaller and more severe subset of AMI.

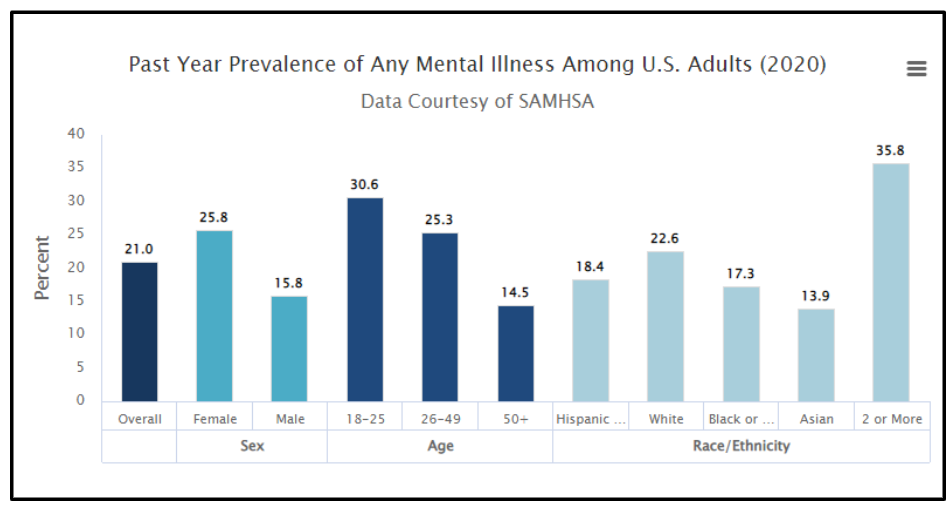

The below charts in figure 9.3 show the prevalence of AMI and SMI among adults in 2020, and the bottom chart shows the rates of any mental illness in adolescents. There are some group-level differences in this data that are important to notice. The prevalence of AMI among women is much higher than that of men; there is a 10 percent gap between the two groups. Why might this be?

Figure 9.3 Prevalence of Any Mental Illness. Image Description:

- In 2020, there were an estimated 52.9 million adults aged 18 or older in the United States with AMI. This number represented 21 percent of all U.S. adults.

- The prevalence of AMI was higher among females (25.8 percent) than males (15.8 percent).

- Young adults aged 18–25 years had the highest prevalence of AMI (30.6 percent) compared to adults aged 26–49 years (25.3 percent) and aged 50 and older (14.5 percent).

- The prevalence of AMI was highest among the adults reporting two or more races (35.8 percent), followed by White adults (22.6 percent). The prevalence of AMI was lowest among Asian adults (13.9 percent).

For now, we will focus on just one of the bars on this graph: the 35.8 percent of people who experience any mental illness who report as two or more races. We’ll look at two factors that might influence the mental health of multiracial people: legal history and double-discrimination, although there are many more contributing factors.

9.2.2.2 Activity: Neither One or the Other: The Social Construction of Mixed Race

|

Figure 9.4 President Barack Obama is a mixed-race person who identifies as Black

Figure 9.5 Vice President Kamala Harris Former U.S. President Barack Obama and current Vice President Kamala Harris may be among the most famous U.S. people who are multiracial. Obama’s mother was White from Kansas. His father was Kenyan from the Luo tribe. Although he is mixed race, he self-identifies as African American. Vice President Kamala Harris identifies as American. In most of her political work, she labels herself Black, often because mixed race wasn’t a choice. Her mother was South Asian from India, and her father was Black from Jamaica. This article from Pew Research, “In Kamala Harris we can see how America has changed,” describes several demographic trends of “mixing” that are occurring recently in the United States. People from different races have always had relationships with each other. Sometimes, in the cases of slavery, these relationships have been nonconsensual. The laws against miscegenation, or the mixing of two races, were only overturned at the federal level in the United States in 1967, less than 50 years ago. (Grieg 2013). In fact, “the 2000 Census was the first time that citizens of the United States could select multiple racial categories for self-identification apart from Hispanic ethnicity in a census.” (Whaley & Francis 2006). The lack of legal, governmental, and systems recognition of multiracial identity itself is an additional stress for multiracial people. To learn more, check out this blog, Laws that Banned Mixed Marriages. A second contributing factor to mental health risks for multiracial people is double-discrimination, the concept that you experience discrimination from both of your communities. In this popular media article about Kamala Harris quotes Diana Sanchez, a professor who studies multiracial identity:

If you want to learn more about the experience of mixed-race people, check out Do All Multiracial People think the Same? [YouTube Video]. What is your own experience? |

Figure 9.6 Prevalence of Serious Mental Illness 2020

Image Description:

- In 2020, there were an estimated 14.2 million adults aged 18 or older in the United States with SMI. This number represented 5.6% of all U.S. adults.

- The prevalence of SMI was higher among females (7.0%) than males (4.2%).

- Young adults aged 18-25 years had the highest prevalence of SMI (9.7%) compared to adults aged 26-49 years (6.9%) and aged 50 and older (3.4%).

- The prevalence of SMI was highest among the adults reporting two or more races (9.9%), followed by American Indian / Alaskan Native (AI/AN) adults (6.6%). The prevalence of SMI was lowest among Native Hawaiian / Other Pacific Islander (NH/OPI) adults (1.2%).

For the graph in figure 9.6, we will focus on the different prevalence of serious mental illness between women and men. Worldwide, women are more likely than men to experience mental health issues (Andermann, 2010). Before we commonly held the conclusion that women are just more emotional, however, we need to consider other factors. Women are more likely in their lives to experience violence and go hungry. In the article, Culture and the social construction of gender: Mapping the intersection with mental health, psychiatrist Lisa Andermann calls us to look beyond individual explanations of women’s mental health and explore structural factors:

Identifying the psychosocial factors in women’s lives linked to mental distress, and even starting to take steps to correct them, may not be enough to reduce rates of mental illness or improve well-being of women around the world. More studies which take into account the interaction between biological and psychosocial factors are needed to explore the perpetuating factors in women’s mental health, and explain why these problems continue to persist over time and suggest strategies for change. And for these changes to occur, health system inadequacies related to gender must be addressed. (Andermann 2010)

In section 9.4 of this chapter we look at the structures of patriarchy that impact all of our lives.

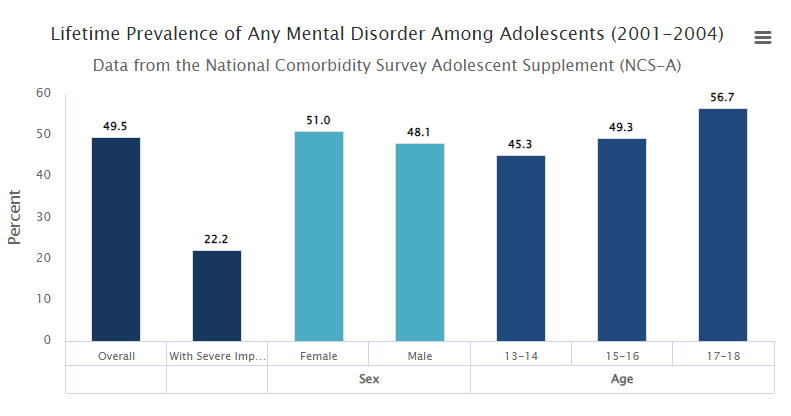

Figure 9.7 Prevalence of Any Mental Disorders Among Adolescents Almost half of all teenagers report a mental disorder. What do you think might cause such a high rate? Image Description:

- Based on diagnostic interview data from National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A), Figure 5 shows lifetime prevalence of any mental disorder among U.S. adolescents aged 13-18.1

- An estimated 49.5% of adolescents had any mental disorder.

- Of adolescents with any mental disorder, an estimated 22.2% had severe impairment. DSM-IV based criteria were used to determine impairment level.

When 21 percent of all adults have a mental illness and almost half of all teenagers have mental disorders, as demonstrated in figure 9.7, the condition goes beyond being a personal trouble, and enters the realm of public issue. The Teen Mental Health Crisis Caused by COVID [YouTube Video] tells the story of the increase in teen suicide with the COVID-19 pandemic. Because this video recreates the experience of a parent who’s child committed suicide, please skip it if you may experience harm.

Why is there such a wide difference between teenagers and adults? It’s hard to say for sure, but research offer three options:

Biology: Scientists are mapping changes in the brain in much more detailed ways. During adolescence, the wiring of the brain changes significantly, adding connections, particularly connections related to executive planning and regulation. Pruning these connections is also happening, when particular pathways are not being used. Related to these changes in brain and hormones (Giedd et al., 2008). In addition, the onset for 50 percent of adult mental health disorders occurs by age 14, and for 75 percent of adults by age 24 (Kessler, 2007).

Inclusion in data: Other researchers suggest that part of the difference between the two age groups has to do with being able to contact people. Many youth are still connected with school and family, even if they are experiencing mental health issues. Most mental health surveys don’t contact people in residential living, including assisted living, group homes, or prison or jail. Also, they do not contact people who are houseless. Also, young people who took their own lives would of course not be included in adult statistics. Because of this mental health issues in adult and senior populations may be significantly under reported (Kessler & Wang, 2008).

More stress, less stigma: Also, researchers are exploring whether the increase in reporting of mental health issues for teens and young adults is due to experiencing more stressors or experiencing less stigma around reporting mental health concerns. This article, Why Gen Z is More Open in Talking about Their Mental Health explores this conundrum.

What other reasons might you think the two populations would be different? Can you find any evidence?

9.2.3 Conflict in values

One major conflict in values we see in the social problem of mental health and mental illness is the value of community care versus the efficacy of medical care. Historically, many people with mental illnesses were institutionalized. Many state hospitals provided essential care. People were isolated from their families and communities and significantly stigmatized. Also, because these facilities were often locked, outside oversight was often limited. In 1955 there were over half a million people who were hospitalized (Talbott 2004).

Since this high, the institutionalized population has decreased by almost 60 percent. Some of that decrease is due to a change in values. Talbott writes, “the impact of the community mental health philosophy that it is better to treat the mentally ill nearer to their families, jobs, and communities.” This perspective humanizes people with this condition.

Unfortunately, government funding for community mental health services and other social supports is insufficient to meet the need. Instead of finding wrap around support, many people who were deinstitutionalized became homeless instead.

9.2.4 Socially constructed but real in consequences

Health consists of mental well-being as well as physical well-being, and people can suffer mental health problems in addition to physical health problems. Scholars disagree over whether mental illness is real or, instead, a social construction. The predominant view in psychiatry, of course, is that people do have actual problems in their mental and emotional functioning and that these problems are best characterized as mental illnesses or mental disorders and should be treated by medical professionals (Kring & Sloan 2010).

But other scholars, adopting a labeling approach, say that mental illness is a social construction or a “myth” (Szasz, 2008). In their view, all kinds of people sometimes act oddly, but only a few are labeled as mentally ill. If someone says she or he hears the voice of an angel, we attribute their perceptions to their religious views and consider them religious, not mentally ill. But if someone instead insists that men from Mars have been in touch, we are more apt to think there is something mentally wrong with that person. Mental illness thus is not real but rather is the reaction of others to problems they perceive in someone’s behavior.

This intellectual debate notwithstanding, many people do suffer serious mental and emotional problems, such as severe mood swings and depression, that interfere with their everyday functioning and social interaction. Sociologists and other researchers have investigated the social epidemiology of these problems. Several generalizations seem warranted from their research (Cockerham, 2011).

9.2.5 Unequal outcomes

First, social class affects the incidence of mental illness. To be more specific, poor people exhibit more mental health problems than richer people: they are more likely to suffer from schizophrenia, serious depression, and other problems (Mossakowski 2008). A major reason for this link is the stress of living in poverty and the many living conditions associated with it. One interesting causal question here, analogous to that discussed earlier in assessing the social class—physical health link, is whether poverty leads to mental illness or mental illness leads to poverty. Although there is evidence of both causal paths, most scholars believe that poverty contributes to mental illness more than the reverse (Warren 2009).

Figure 9.8 Jessica B – Self Portrait of Depression. Why are women more likely than men to be seriously depressed?

Women are more likely than men to be seriously depressed. Sociologists attribute this gender difference partly to gender socialization that leads women to keep problems inside themselves while encouraging men to express their problems outwardly.

Second, there is no clear connection between race/ethnicity and mental illness, as evidence on this issue is mixed: although many studies find higher rates of mental disorder among people of color, some studies find similar rates to Whites’ rates (Mossakowski, 2008). These mixed results are somewhat surprising because several racial/ethnic groups are poorer than Whites and more likely to experience everyday discrimination, and for these reasons should exhibit more frequent symptoms of mental and emotional problems. Despite the mixed results, a fair conclusion from the most recent research is that African Americans and Latinos are more likely than Whites to exhibit signs of mental distress (Mossakowski 2008; Jang et al., 2008; Araujo & Borrell 2006).

Third, gender is related to mental illness but in complex ways, as the nature of this relationship depends on the type of mental disorder. Women have higher rates of bipolar disorders than men and are more likely to be seriously depressed, but men have higher rates of antisocial personality disorders that lead them to be a threat to others (Kort-Butler 2009; Mirowsky & Ross 1995). Although some medical researchers trace these differences to sex-linked biological differences, sociologists attribute them to differences in gender socialization that lead women to keep problems inside themselves while encouraging men to express their problems outwardly, as through violence. To the extent that women have higher levels of depression and other mental health problems, the factors that account for their poorer physical health, including their higher rates of poverty, stress, and rates of everyday discrimination, are thought to also account for their poorer mental health (Read & Gorman 2010).

Although people rarely take to the streets to protest mental illness, mental health is a social problem. In the next section, we’ll look deeper at the inequalities related to mental health, and explore some of the causes of that inequality.

9.2.6 Licenses and Attributions for The Basics: Mental Health and Mental Illness as a Social Problem

“Mental Health and Mental Illness” by Kate Burrows is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.2 The Mental Health and Well-being Continuum from “Enhancing Public Mental Health and Wellbeing Through Creative Arts Participation” is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Figure 9.3 Prevalence of Any Mental Illness https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness Public Domain

Figure 9.4 Barack Obama Official White House Photo by Pete Souza, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:President_Barack_Obama.jpg

Public Domain

Figure 9.5 Vice President Kamala Harris Lawrence Jackson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kamala_Harris_Vice_Presidential_Portrait.jpg Public Domain

Figure 9.6 Prevalence of Any Mental Illness https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness Public Domain

Figure 9.7 Prevalence of Any Mental Disorders Among Adolescents https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness Public Doman

Figure 9.x Jessica B – Week Five – Face of depression… – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

9.2.2.3 Socially Constructed but real in consequences and 9.2.2.4 Unequal Outcomes

https://open.lib.umn.edu/sociology/chapter/18-3-health-and-illness-in-the-united-states/

Sociology by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Light editing