9.5 Mental Health: Models and Treatments

In this section, we explore the different models of mental health and mental illness. These models come to us from different academic disciplines—psychology, psychiatry, and sociology. All three have something to offer to help us understand mental health and mental illness. We also consider some of the main treatments for mental illness.

9.5.1 Medical and Psychological Models of Mental Health and Mental Illness

Cultural views and beliefs about mental illness have varied enormously over the course of history. For example, ancient humans once believed thatmental illness was caused by the influence of evil spirits over the afflicted person. Accordingly, treatments back then involved removing part of the patient’s skull to allow the demon to escape. Later, during the Middle Ages, mental illness was thought to be connected to the moon (hence the term lunacy). Another common belief was that a person with mental illness was being punished by God.

Fortunately, we’ve come a long way since then. However, scientists are still struggling to pinpoint exactly what causes mental illness. Most people, however, agree that mental illness can be influenced by a variety of things, including biological factors, personal history and upbringing, and lifestyle. To help provide a framework for understanding these potential causes, experts have developeda number of different models, which we’ll explore here.

9.5.1.1 Biological model

The biological model of mental illness approaches mental health in much the same way an MD would approach a sick or injured patient: they look for problems or irregularities in the body that are causing the symptoms. Adherents of the medical model believe that mental illness is primarily caused by biological factors such as abnormal brain chemistry or genetic predisposition.

9.5.1.2 Medical model

The medical model of mental illness has proven to be true in many cases. For example, depression has long been linked to deficiencies in certain neurotransmitters, and schizophrenia has been shown to run in families. Science like this forms the basis of psychopharmacology, which seeks to treat mental illness with medication that adjusts the level of neurotransmitters present in the brain. However, critics of the medical model believe that it is too simple because it ignores important nonbiological factors in a person’s life.

9.5.1.3 Psychological model

As you might expect, in the psychological model of mental illness, psychologists look at psychological factors to explain and treat mental illness. For example, they look at attachment theory, which is a theory that examines how you relate to other people. In fact, there are over 400 different psychological models of therapy—there is a right model for everybody, and a psychologist’s or therapist’s job is to figure out which of those models work for which patient. Of course, psychologists have preferences and skill sets—no psychologist can practice 400 forms of psychotherapy!

9.5.1.4 Psychosocial model

Psychologists also recognize that social factors impact mental health. This model is called the psychosocial model of mental illness. The psychosocial approach focuses on how an individual interacts with and adapts to their environment. Specific factors of interest might include a person’s relationships, any past trauma, economic situation, and their outlook on life, including religious beliefs.

Stress—both good and bad—can affect your mental health, and psychologists pay attention to where these stressful areas are. In fact, starting a new job is in the top three stressful things—but most people are happy to start new jobs. Happiness aside, the new expectations, roles, and attitudes that you find at your new workplace, cause stress. Of course, negative things can also cause stress, and psychologists help people develop resilience against this sort of stress so they can successfully navigate the stressful situation.

Another thing psychologists take into account are your social roles. Having conflicting social roles—such as being a parent during Covid and having a full-time job, is a role conflict that can cause stress. There are several different kinds of role strain—including when one role takes up too much of the time you need to dedicate to other roles, or when two different roles compete with each other.

As the name implies, the psychosocial model focuses on the importance of psychological and social factors in informing a person’s mental health. Rather than looking to a person’s brain for clues, a proponent of the psychosocial model of mental illness might look to a patient’s personal history, their attitude, beliefs, and life circumstances to better understand their mental illness.

9.5.1.5 Biopsychosocial model

But the psychosocial model is also limited, because it doesn’t take biological or genetic factors into account. To address this, psychologists and psychiatrists have developed the biopsychosocial model of mental illness, which addresses the idea that mental health problems are caused by a combination of biological, sociological, and psychological features.

For example, it can be true that a patient has a biological disposition to mental illness and that they have experienced trauma that is causing or exacerbating their symptoms. Similarly, many patients have discovered that a combination of psychotropic medication and talk therapy is helpful in addressing their mental health issues. In fact, many mental health care providers integrate both approaches into a more holistic framework called the biopsychosocial model.

9.5.2 Sociological Approaches to Mental Illness

Mental illness, as the eminent historian of psychiatry Michael MacDonald once aptly remarked, “is the most solitary of afflictions to the people who experience it; but it is the most social of maladies to those who observe its effects” (MacDonald 1981:1). It is precisely the many social and cultural dimensions of mental illness, of course, that have made the subject of such compelling interest to sociologists. They have responded in a huge variety of ways to the enormously wide social ramifications of mental illness, and the inextricable ways in which the cultural and the social are implicated in what some might view as a purely intrapsychic phenomenon.

If psychiatry has typically, though far from always, focused on the individual who suffers from various forms of mental disorder, for the sociologist it is—naturally—the social aspects and implications of mental disturbance for the individual, for his or her immediate interactional circle, for the surrounding community, and for society as a whole, that have been the primary intellectual puzzles that have drawn attention.

How, for example, are we to define and draw boundaries around mental illness, and to distinguish it from eccentricity or mere idiosyncrasy, to draw the line between madness and malingering, mental disturbance and religious inspiration? Who has the social warrant to make such decisions? Why? Do such things vary temporally and cross-culturally? How have societies responded to the presence of those who do not seem to share our commonsense notions of reality? Who embrace views of reality that strike others as delusional? Who sees objects and hears voices invisible and inaudible to the rest of us? Who commits heinous offenses against law and morality with seeming indifference? Or whose mental life seems so denuded and lacking in substance as to cast doubt on their status as autonomous human actors?

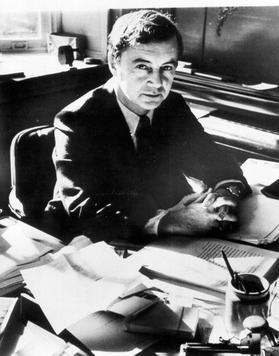

Figure 9.17 Erving Goffman, Canadian born Jewish sociologist Erving Goffman researched mental health, mental illness. His book Stigma is essential in understanding the social construction of difference.

Mental illness has profoundly disruptive effects on individual lives and on the social order we all take for granted. Erving Goffman (figure 9.17), whose mid-twentieth century writings still constitute some of the most provocative and profound sociological meditations on the subject is perhaps best-known for his searing critique of mental hospitals as total institutions.

Accepting, then, that there is such a thing as mental illness (all the while acknowledging that some sociologists and even some renegade psychiatrists have questioned its reality, and still others have debated its designation as a specifically medical problem), a whole series of further questions then arise: How much of it is there, and how do we know, if indeed we do? What is its social location? Does that differ by class, by age, by gender, by race, by ethnicity, and so forth? Do these social variables have implications for the way mental illness is reacted to and socially managed? What are the costs of such episodes of mental disturbance to individuals, families, and society as a whole, and how are those costs distributed?

How have societies characteristically responded to mental illness, and what institutions have they constructed to contain and perhaps cure it? What changes in these responses have occurred over time, and what accounts for these changes? How has mental illness been conceptualized by professionals, but also by the laity? And how have these differing cultural meanings been captured, refracted, and distorted in popular culture? One could go on, but the vital importance of a sociological perspective on mental illness should by now be apparent.

From the late nineteen-sixties through the nineteen-eighties, the intellectual distance and even hostility between sociologists and psychiatrists often seemed to be growing. Within five years of the appearance of Goffman’s groundbreaking book Asylums, the California sociologist Thomas Scheff had authored an in some ways still more radical assault on psychiatry, dismissing the medical model of mental illness and attempting to replace it with a societal reaction model, wherein mental patients were portrayed as victims—victims, most obviously, of psychiatrists (Scheff, 1966). Noting that despite centuries of effort, “there is no rigorous knowledge of the cause, cure, or even the symptoms of functional mental disorders”, he argued that we would be better off adopting “a [sociological] theory of mental disorder in which psychiatric symptoms are considered to be labeled violations of social norms, and stable ‘mental illness’ to be a social role.” And “societal reaction [not internal pathology] is usually the most important determinant of entry into that role” (Scheff 1966:pp. 25).

During the 1960s and 1970s, the societal reaction theory of deviance enjoyed a broad popularity and acceptance among many sociologists, and Scheff’s was one of the principal works in that tradition. But besides attracting derision and hostility from psychiatrists (Roth 1973), where they deigned to notice his work at all, it came under increasing criticism from within sociology on both theoretical (Morgan 1975) and empirical (Gove 1970; Gove & Howell 1974) grounds. In the face of an avalanche of well-founded objections, Scheff was eventually forced to back away from many of his more extreme positions, and by the time the third edition of his book appeared (Scheff 1999), most of its bolder ideas had been quietly abandoned. Labeling and stigmatization of the mentally ill have remained important subjects for sociologists, even if few would now argue that they have the significance once attributed to them.

Though the skeptical claims of the labeling theorists have now been sharply curtailed, much of the sociological work being done on mental illness has retained its critical edge. Four major inter-related changes have occurred in the psychiatric sector in the past half century or so: the progessive abandonment of the prior commitment to hospitalization for patients for life when they have serious mental illness, and the rundown of the state hospital sector; the collapse of psychoanalysis and its replacement by a renewed emphasis on the biological basis of mental illness.

Deinstitutionalization, for example, was initially presented as a grand reform, ironically just as the mental hospital had originally been (Rothman 1971; Scull 1979/1993). From the mid-nineteen-seventies, however, a more skeptical set of perspectives emerged. Psychiatrists had assumed that the new generation of antipsychotic drugs had been the main drivers of the expulsion of state hospital patients. However, in reality it was a political and economic decision by the federal government to close mental hospitals because they were expensive and overcrowded. Also, there was a move toward community mental health, which provides a patient centered approach, but these services were not sufficiently funded. Also, there are not enough beds in current hospitals, in psychiatric wards, for the people who really need them.

In addition, the hegemony of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) began to attract attention, with critics examining both the processes by which the successive editions had been produced, and the intended and unintended effects of its widespread use (Kirk & Kutchins 1992; Kutchins 1997; Horwitz & Wakefield 2007). The sources and the impact of the psychopharmacological revolution drew increased interest, with attention paid to both the role of the pharmaceutical industry and changes in the intellectual orientation of the psychiatric profession (Healy 1997/2002; Herzberg 2008).

Scholars working on the sociology of mental illness thus now confront a very different research environment than the one that prevailed a quarter century ago. The range of intellectual and policy issues thrown up by the dramatic changes that have marked the mental health sector in the same period mean, however, that there is an abundance of challenging topics for the study of which sociological perspectives are indispensable.

9.5.3 Licenses and Attributions for Mental Health: Theories

“Mental Health Theory” by Kate Burrows is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

9.5.2 The Sociological Study of Mental Illness in America adapted from The Sociological Study of Mental Illness: A Historical Perspective (c) Andrew Scull, Mad in America: Science, Psychiatry, and Social Justice. All rights reserved. Used and adapted with permission.

Figure 9.17 Erving Goffman https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Erving_Goffman.jpg from the American Sociological Association, Fair Use.