4 Photography

Foundations of Photography

As we move through the world today, snapping cell phone photos left and right, a look at the history of photography and visual characteristics of the medium will open doors for your exploration. In this chapter, you will have a chance to think about early photographic processes, to practice visual analysis introduced in an earlier chapter, and to make connections to elements of New Media Art (from the Introduction) and to other genres of New Media Arts.

Analog and then Digital Photography

As you sort through the variety of ways of making photographs, recognize the larger and more traditional category of analog photography, photographs made from film negatives, for example; and the newer category of digital photography, photographs made from your cell phone, for example. Analog photographs are expressed through physical materials, like paper, glass, metal, and chemical combinations. Digital photographs are expressed through binary code, that is the combinations of 1’s and 0’s that a computer needs to display the image as a .jpg or other type of image file.

The chapter on digital photography explores ways that analog photography has maintained a place in our digital world. Here, you can look closely at the origins of analog photography. First, consider visual analysis and the elements of New Media Art that are tightly tied to photography.

Visual Analysis and Photography

In the chapter Visual Analysis and New Media Arts, you looked at the vocabulary of visual analysis. Since photographs are made with light, the qualities of light that you see in the work is a good place to start when analyzing.

Also, traditional photography made use of one aperture (or eye of the camera). Looking at the world with one eye gives the viewer the sense of one-point perspective (like looking in a tunnel), so space is another visual element to explore.

When considering the composition of a photograph, look to see how the photographer has arranged the photograph to produce implied line.

Visual textures also add to the ways that you read photographs.

As you analyze light, line, space, and texture in photographs, ask yourself, “What impact do these qualities have on the work or on the way that I read and interpret it? As a foundational medium of time-based arts, how does it challenge my understanding of time?”

Elements of New Media Art in Photography

As you explore the foundations of photography, notice when you recognize these elements of New Media Art.

- How does photography expand the definition of art?

- How does photography democratize access to art?

- How do photographers exploit new technology for artistic purposes?

- How does photography merge new media with old media?

- How does photography capture a moment in time, or expresses time in other ways?

- How are photographs replicable? How can images be copied multiple times and exist in different states?

- What other elements of New Media Art are found in photography?

A Brief History of Photography

Camera Obscura

Long before experiments in printmaking led to a fixed image created by light in the early 1800s, the camera obscura was being used by scientists for observation and by artists as a tool to draw and paint. A camera obscura is literally a chamber that is dark; a dark room.

Look at these images and think carefully about how the camera obscura works.

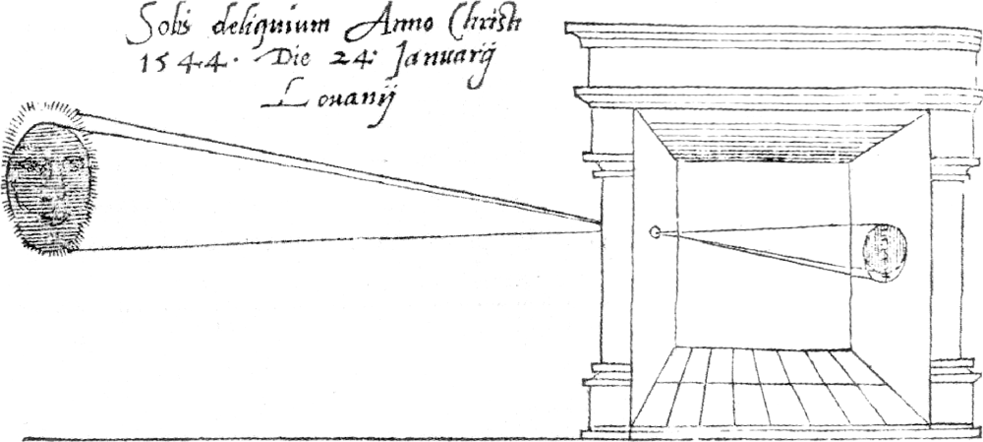

Scientists have used the camera obscura as a way to view celestial bodies and astronomical occurrences. In this diagram from 1545, the image of the solar eclipse on the left is projected through the hole in the wall of the dark room on the right. You can see that the image of the eclipse is upside down and reversed on the opposite wall.

Astronomy fans in North America also used special versions of the camera obscura to view safely the solar eclipse on August 21, 2017.

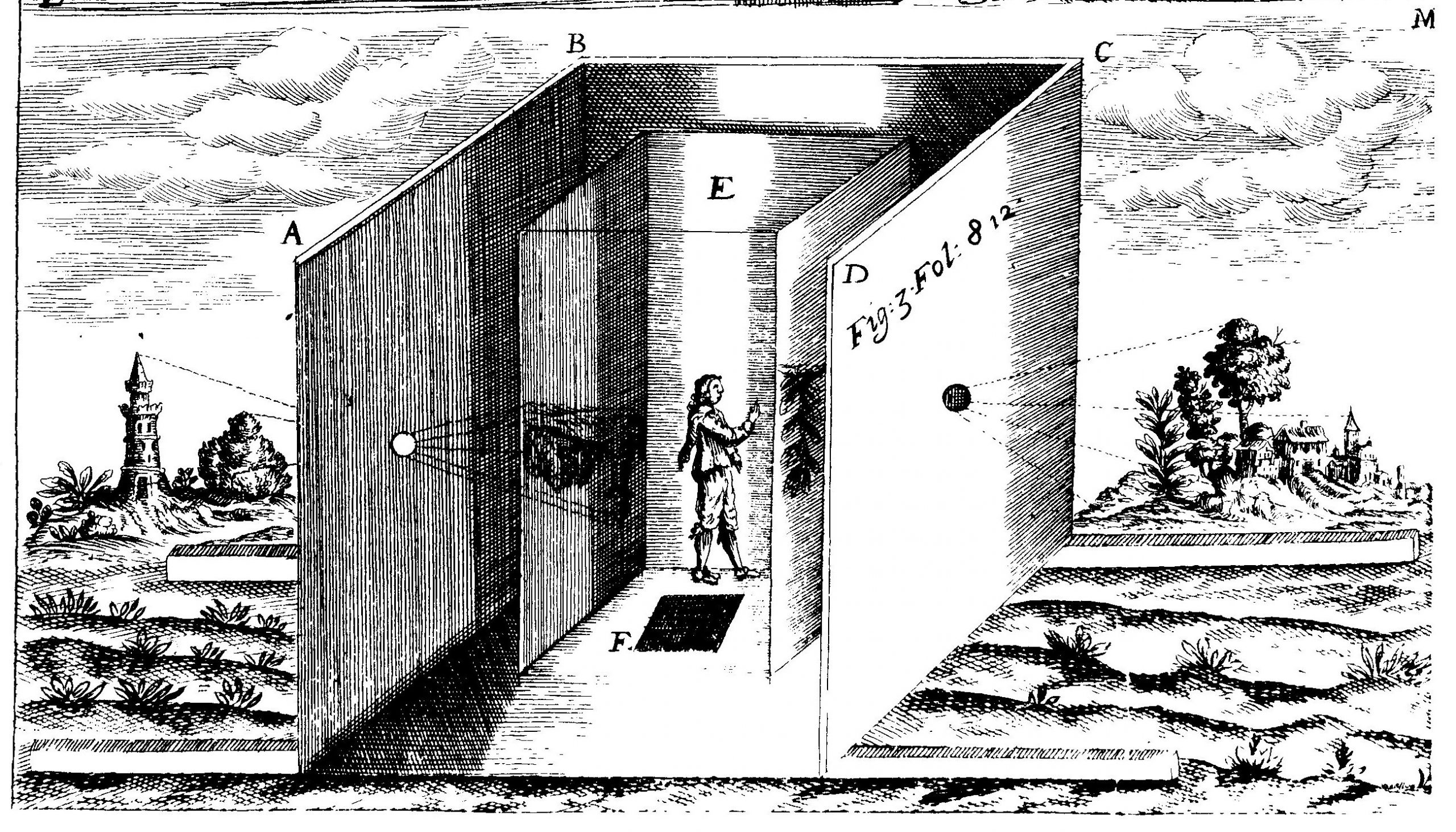

The camera obscura has been used by artists as a way to sketch and plot out composition in drawings and paintings. In this cutaway diagram of a camera obscura from 1646, two images are projected into this camera obscura. The scene with the tower on the left is projected through the hole in the wall upside down and reversed onto the transparent surface in the room behind the artist. The scene with the trees and village on the right is projected through the hole in the other wall onto the transparent surface upside down and reversed. The artist is using the projected image to help sketch the scene.

Contemporary photographer Abelardo Morell (born 1948) has been making camera obscura photographs since the early 1990s. He turns a room into a camera obscura, a dark box, and using another camera, he photographs the dark room with the outside image projected upside down and backwards into the room. Explore the images on his website and see if you can make the connections to the historical process of the camera obscura.

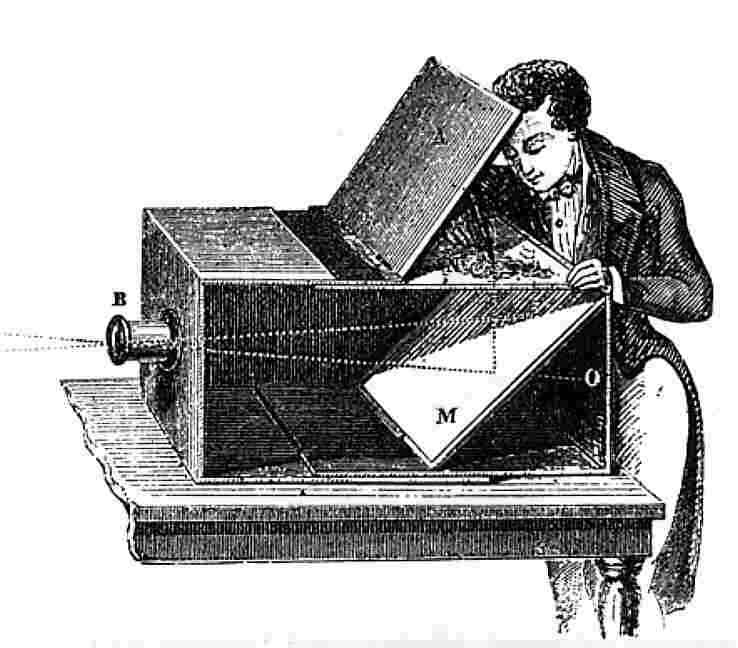

As the camera develops from these practices in art and science, we see the “dark room” becoming more portable and, eventually, the image is fixed using chemicals that react to the light rather than drawing. In the illustration above, the image is projected through the lens (“B”) onto a mirror (“M”) from which the artist can trace onto thin paper and then transfer to canvas or another surface. Note the door (“A”) of the box. The door blocks the outside light so that the projected image remains visible for the artist.

In all of the examples of camera obscuras above, none of them involve a fixed image or images in multiple. It is the development of photography that brings about changes including fixed images and images that could be reproduced.

Basic Parts of a Camera

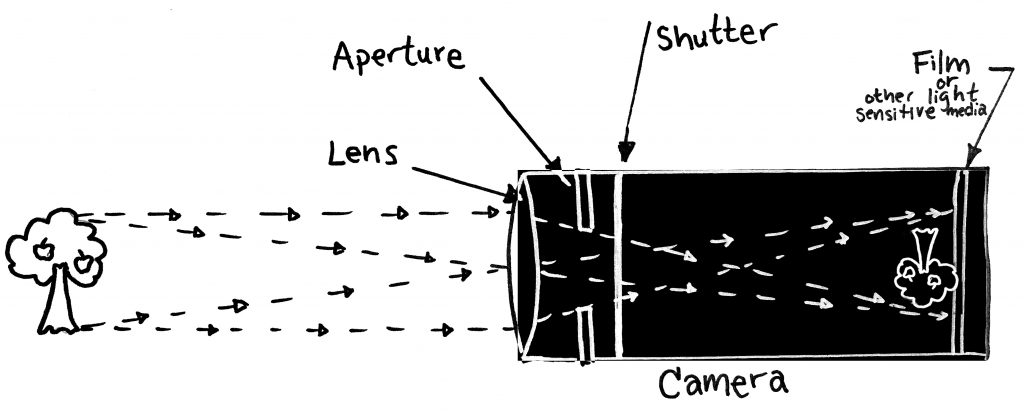

Use the diagram above to think about the parts of the basic, traditional camera.

- Camera – the dark box

- Aperture – the hole through which light and the image is projected. The aperture can be controlled to allow more light in (for example, at night) or less light in in order to impact the exposure. The aperture works like the pupil of the eye.

- Lens – the lens, often shaped glass, like eyeglasses, focuses the image on the back wall of the camera

- Shutter – the shutter opens and closes to control the amount of time that light enters the camera. The shutter is like the eyelid blinking.

- Film or other light sensitive material – as the camera obscura advances, light sensitive material, often containing silver, is used to capture the image that is then fixed and permanent. Think about the way that silver jewelry or silver eating utensils tarnish in the light. Similar basic principles apply in the camera.

The Niépce Heliograph

By the 19th century experimenting often by printmakers and scientists around the world led to simultaneous photographic inventions founded on:

- Fixing the image permanently as a photograph

- Improving the quality of focus and detail in photograph

- Shortening the exposure time, the time it takes to snap a photograph

- Reproducing the photographic image

Joseph-Nicephore Niépce (1765–1833) gets the historical credit for the first fixed photographic image in 1827 (or 1826). He called this a heliograph, or “sun writing.” Niépce set his camera on the windowsill of his studio, pointing it at a tree and the rooftops of neighboring buildings. Inside the camera was a pewter plate coated with light-sensitive bitumen (a type of asphalt). After exposing this plate for a few days (and other plates for a few hours) by leaving the aperture open and keeping the camera still, this image (above) was produced on the surface of the plate. Notice how the sun hits the building walls on both sides of the plate showing that the sunlight is captured as it moves throughout the day, hitting one wall early and the other later.

This heliograph had a very, very long exposure time, and it is a single image. The image is not very clear. As photography develops, you will see improvements like:

- Exposure time decreases

- Lenses that increase the clarity of the image

- The invention of the photographic negative from which multiple photographs can be made of the same image

The Daguerreotype

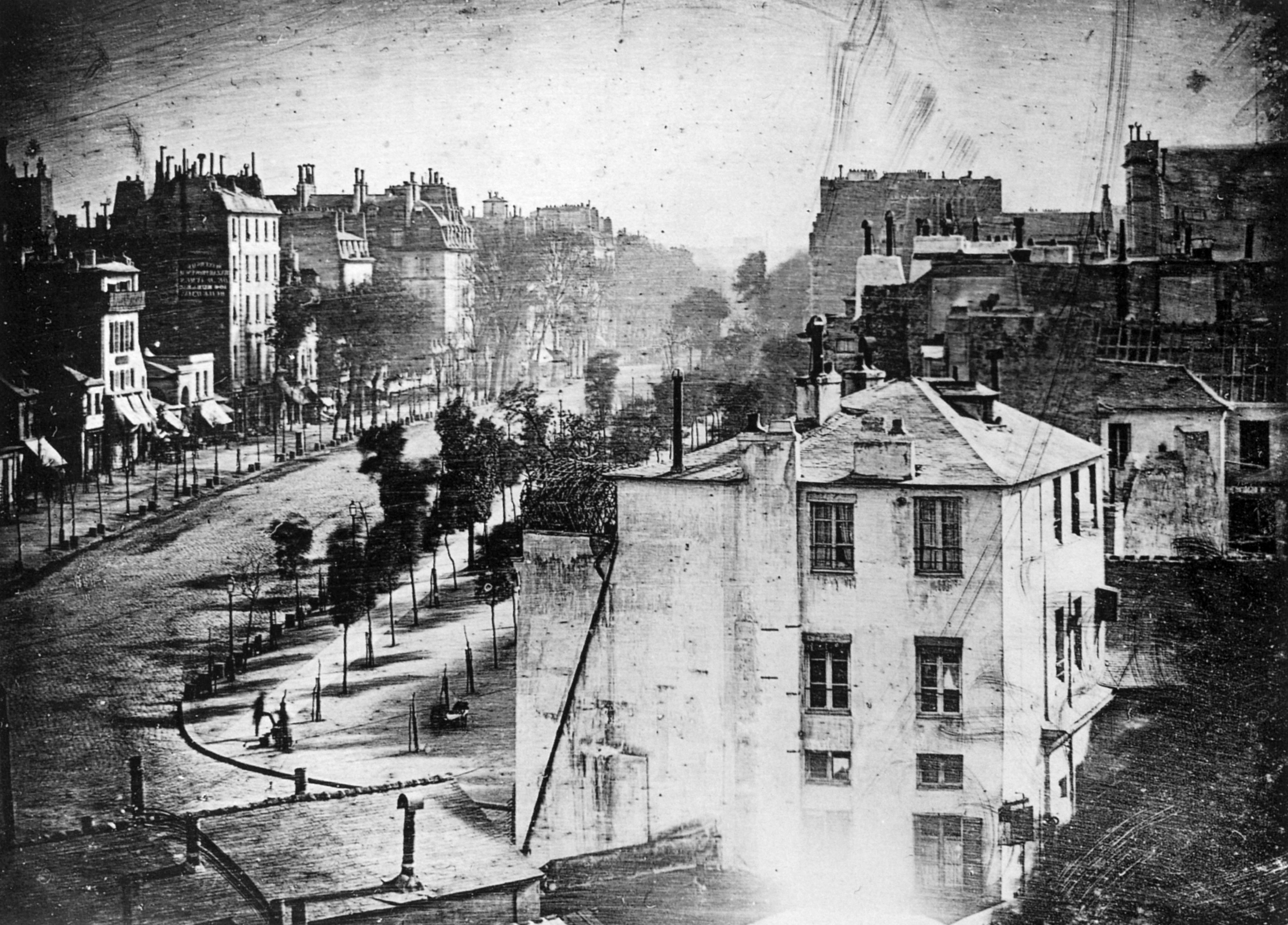

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851) continued improvements to photography with his developments that he called the daguerreotype. Like the heliograph, the daguerreotype is a single image, but the exposure time is much less, about 10-15 minutes.

Daguerre coated a copper plate with a silver substance that reacted to the light projected inside the dark box of the camera. He fixed the image with a salt solution so that the plate would not continue to react to light and to fade. This and improvements to the camera lens produce a crisper image.

The image of a Paris street was taken during the day. Where are all of the people, horses, and carts? The answer is related to the development of photography.

The Calotype (Negative)

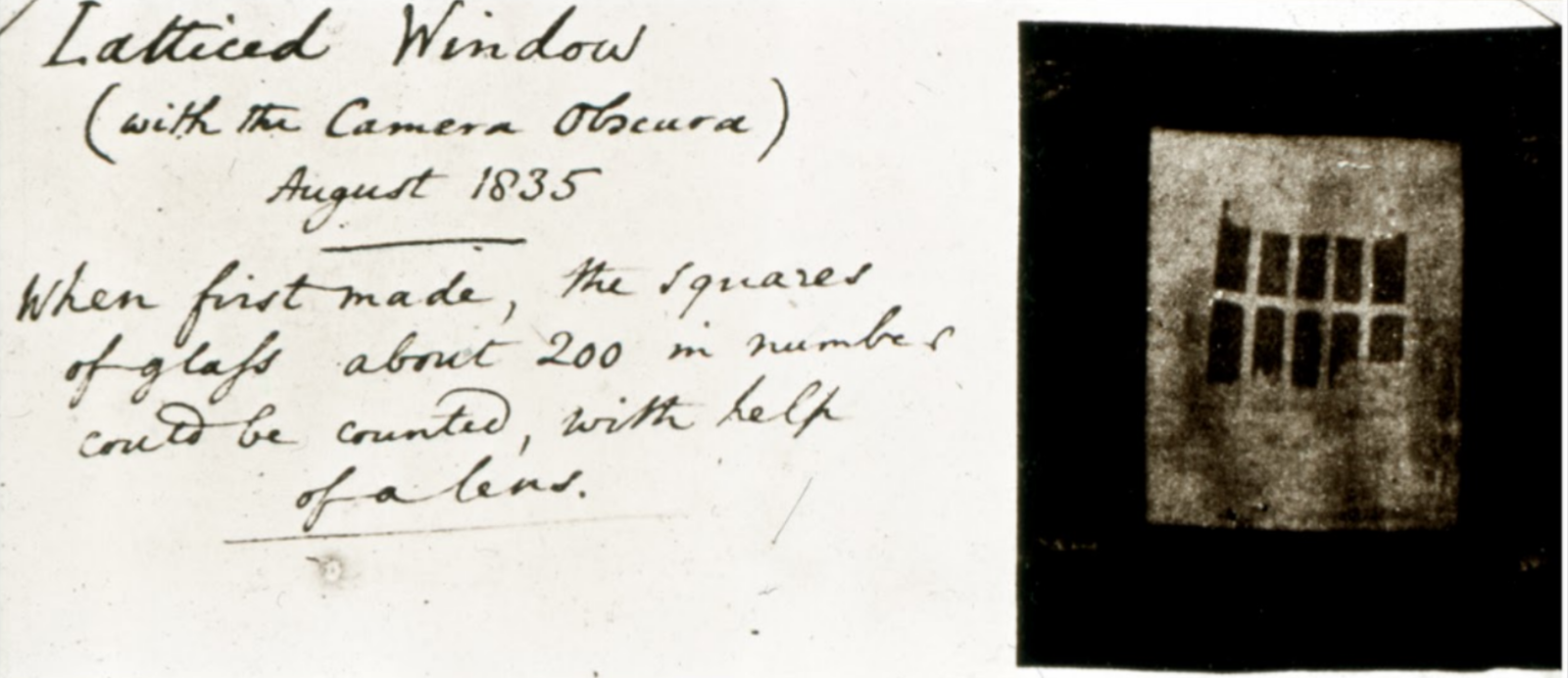

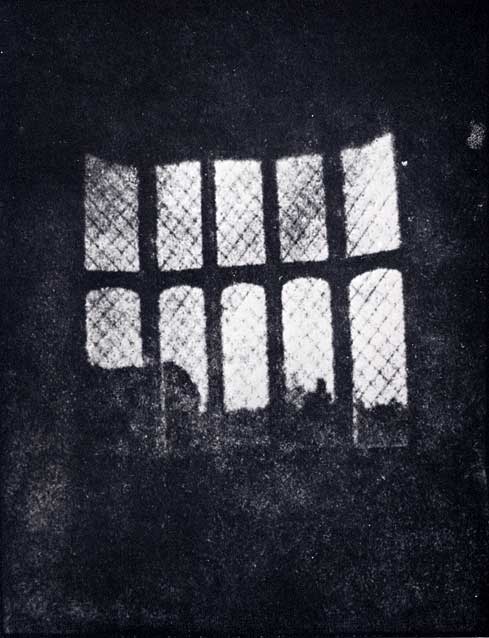

In England, William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) experimented with photographic processes simultaneously with Daguerre. Talbot is credited for inventing the negative and contributed by using paper treated with light sensitive substances for negatives and for prints made from paper. The significance of the calotype negative is that multiple images could be made from a single snap of the camera. Multiple images could then be shared widely.

As you continue to think about the development of photography, compare and contrast this to how photographic images are made and shared digitally today. The Digital Photography chapter explores these processes and photographic possibilities.

Between 1944 and 1946, Talbot published one of the first books containing photographs as illustrations. The photographs were tipped-in prints attached to the pages of text that were made with the printing press. It would take more photographic experimentation by Talbot and others and further developments of the printing press before photographic images could be printed at the same time as text for posters, newspapers, and books. If you would like to explore this, read more about the halftone process, a method of printing photographic images by relying on different densities of dots to express values of light and dark. The Getty Conservation Institute has produced a deep dive into the halftone process.

Stop & Reflect

- Now that you have learned about the invention of the photographic negative, what Elements of New Media Art are expressed by photography and why? Point to qualities of photographs that you have read about so far to help answer this question.

- Before you read further, what other types of image making are tied to photography and why?

- Think about visual analysis and William Henry Fox Talbot’s photographic print The Open Door shown above. After describing the image to your audience, analyze by pointing to details of light and explaining the impact on the work and on the viewer.

Focus: Photography as a Business Tool

Photographs for sale, especially portraits

As photographs became easier, faster, and less expensive to make, the demand grew for photographs and for photographic equipment. Portrait studios sprung up in different parts of the world in the 19th century.

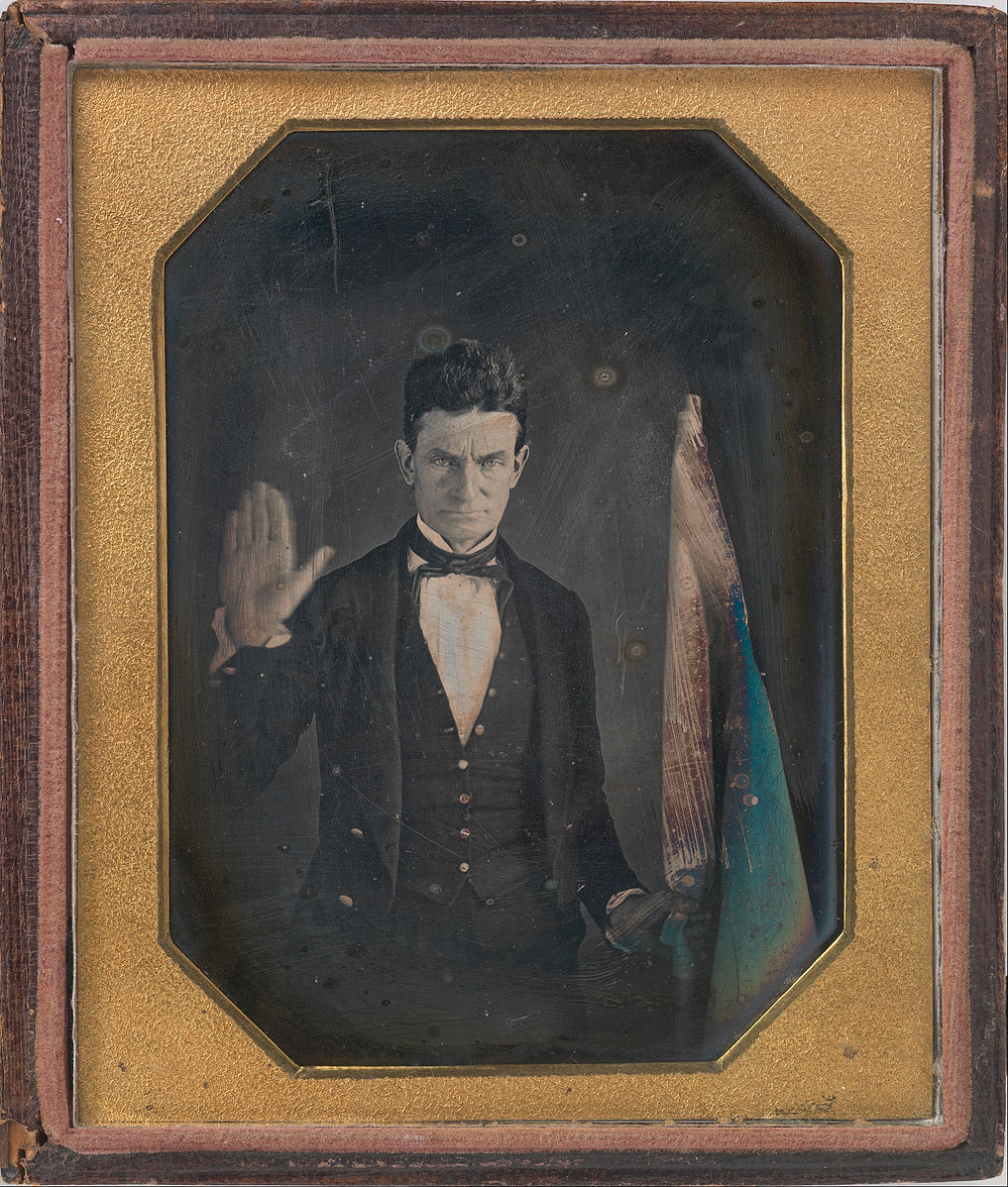

In the United States, Augustus Washington (1820-1875) established a studio to make daguerreotypes in the 1840s in Hartford, Connecticut. As a black man and abolitionist, Washington took advantage of the times to photograph a number of prominent African Americans and abolitionists, a decade later taking his trade and emigrating to Liberia.

In this daguerreotype, Washington poses abolitionist John Brown (1800-1859) with his hand raised in pledge to his cause. The flag in his other hand is thought to be a symbol of his plans to support fugitive slaves as they came north. Here, and in other daguerreotypes with color, the blue-green and red are hand painted after the daguerreotype is made.

In France, in the mid-1800s and on into the Belle Époque (1871-1914), photographs in many different forms were popular. The photographic portrait was extremely popular, especially considering the time-consuming and expensive tradition of painted portraits.

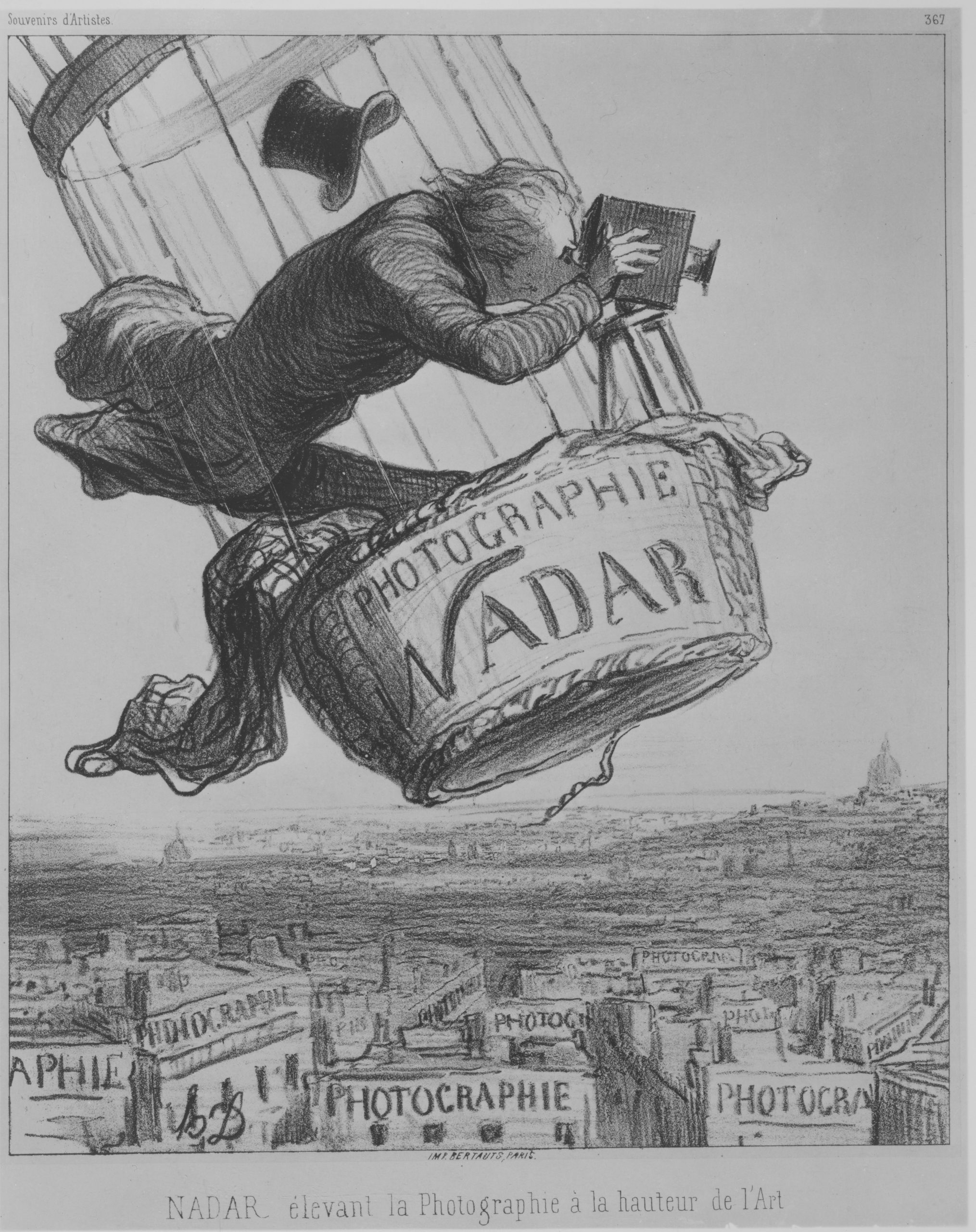

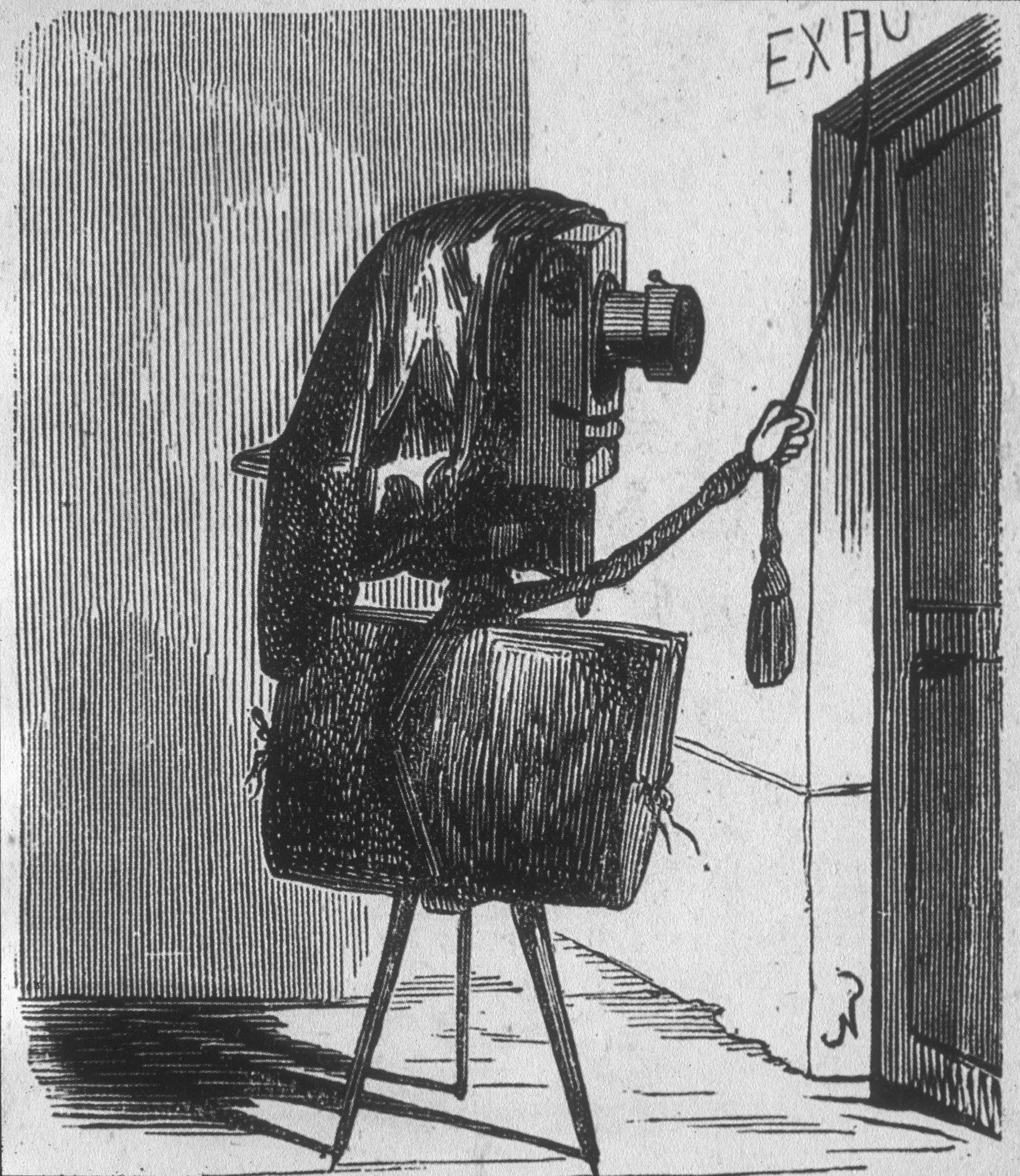

(Gaspard-Félix Tournachon) Nadar (1820-1910) was notable in Paris for his creative uses of the photograph. Here in this lithographic cartoon lampooning Nadar, the photographer takes his camera for a hot air balloon ride to make unique aerial images of the city. The precariousness of his pose shows the risk that photographers would take for their images. Looking below, it seems that the entire city of Paris is made up of photography studios. Not only does this lithograph show the significance of photography as a business in Paris at this time, it also is a response to the debate about the position of photography as a form of art.

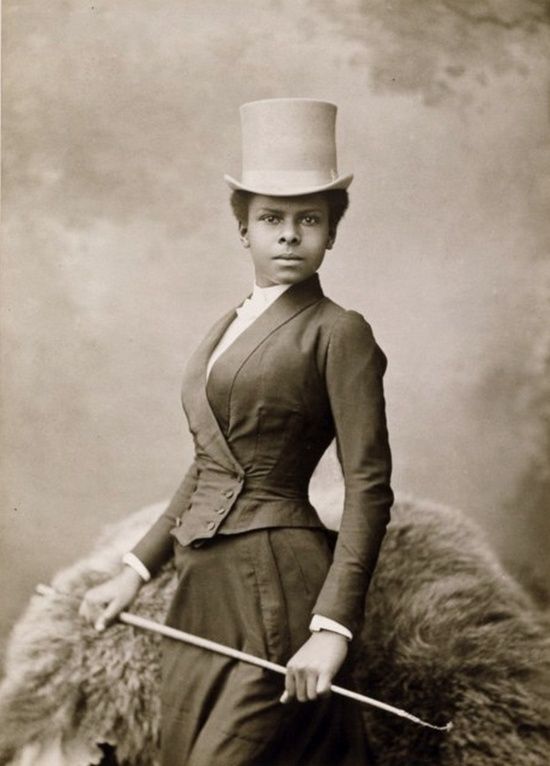

Nadar and his son Paul Nadar (1856-1939) built a successful business in a portrait studio and beyond. They photographed notable figures of the time including Selika Lazevski, a black horsewoman who rode and performed in the Nouveau Cirque in Paris.

In Paris and in other parts of the world, small portrait photographs were produced in multiple, glued onto individual cardboard backings making cartes de visite, “visiting cards” or calling cards. Cartes de visite were traded and collected in albums, and photographic calling cards of celebrities and important figures in society were highly desired.

Stop & Reflect: Portrait Photography

As you view early portrait photography, think about the desire to have portraits in the 19th century and the continued obsession today.

- Can you trace the popularity of nineteenth century portrait photography to our love of portraits today?

- How does the cartes-de-visite compare to the way we use portrait photography today?

- The Seattle Selfie Museum opened in Seattle, Washington in 2020 as a place with creative studio sets in which to photograph yourself using your phone camera. Imagine the experience visiting this museum. How does the phenomenon of this new type of museum relate to portrait photography as a business? How does it relate to the development of photography, from analog to digital?

Marketing cameras and photographic equipment

In 1888, the George Eastman Kodak Company was founded to produce and sell analog cameras and equipment. A look at their marketing campaign over the decades is a telling reflection of social history and the popularity of photography.

The Kodak Girl became a symbol for the company associating photography with freedom and ease. These were also simultaneously themes of the suffrage movements and the phenomenon of the New Woman. The New Woman was the name given to the Modern woman of the early 20th century who challenged roles of women by breaking stereotypical gender barriers and working for women’s rights.

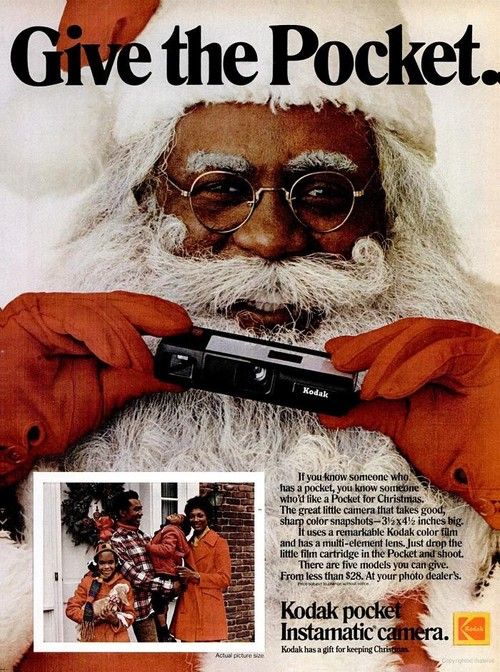

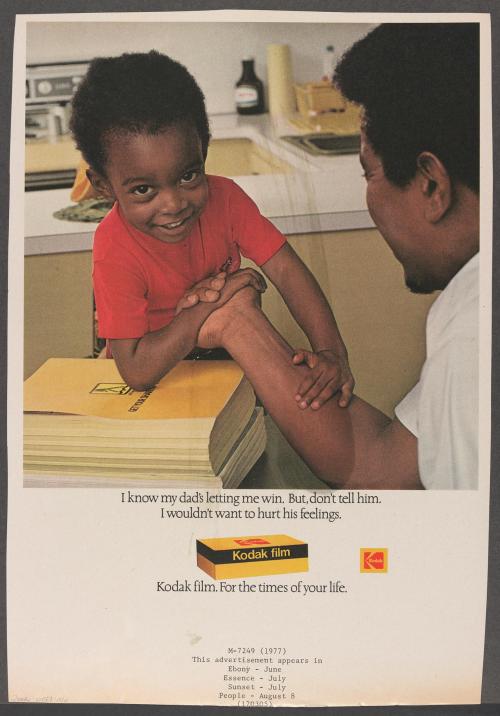

By the 1960s, responding to the Civil Rights movement and the power of the Black consumer, Kodak began advertising to a Black audience in the U.S. through magazines like Ebony and Jet. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the technology behind color recognition of skin pigments was prioritized culturally. For more a brief look at the history of race and camera film in America, check out Vox’s look at the racial bias in photography.

Focus: Women and Photography

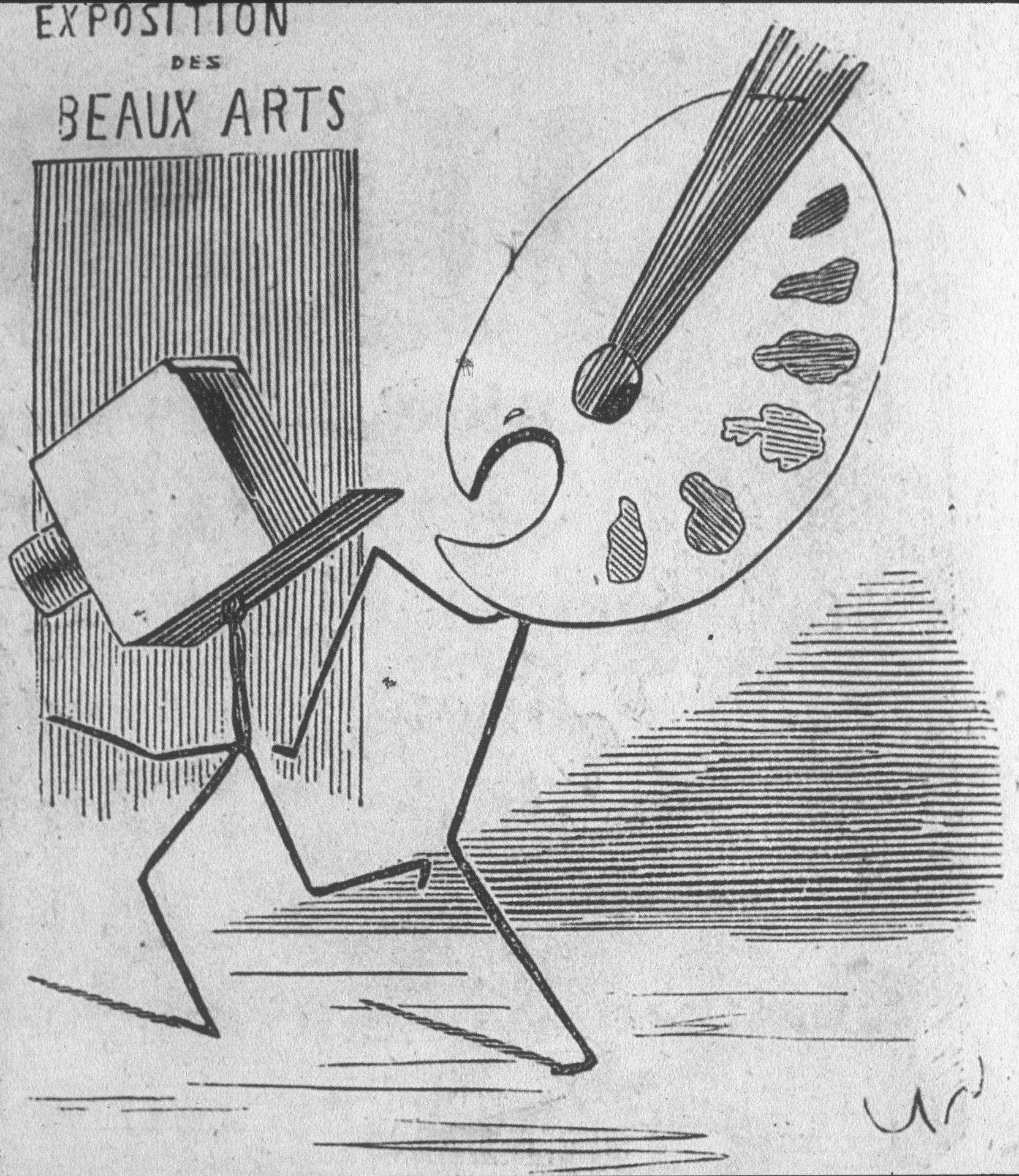

The invention of photography was a major innovation in the 19th century that allowed women a “place” in the arts. Even though photography grew and improved by leaps and bounds, the art Academy had no place for photography. Art Academies, or official art schools, were grounded in traditional media of drawing, painting, and sculpture. At its inception, photography was considered a scientific process and not creative like the fine arts of painting and sculpture. Academicians were threatened by the cheapness and ease of the photograph in producing portraits, for instance. Nadar commented on these biases in humorous cartoons published in Parisian newspapers and magazines in the 1850s.

As a result of photography’s exclusion from the realm of “high art” and the academies, it was a field that women could more easily enter, and they did.

Julia Margaret Cameron

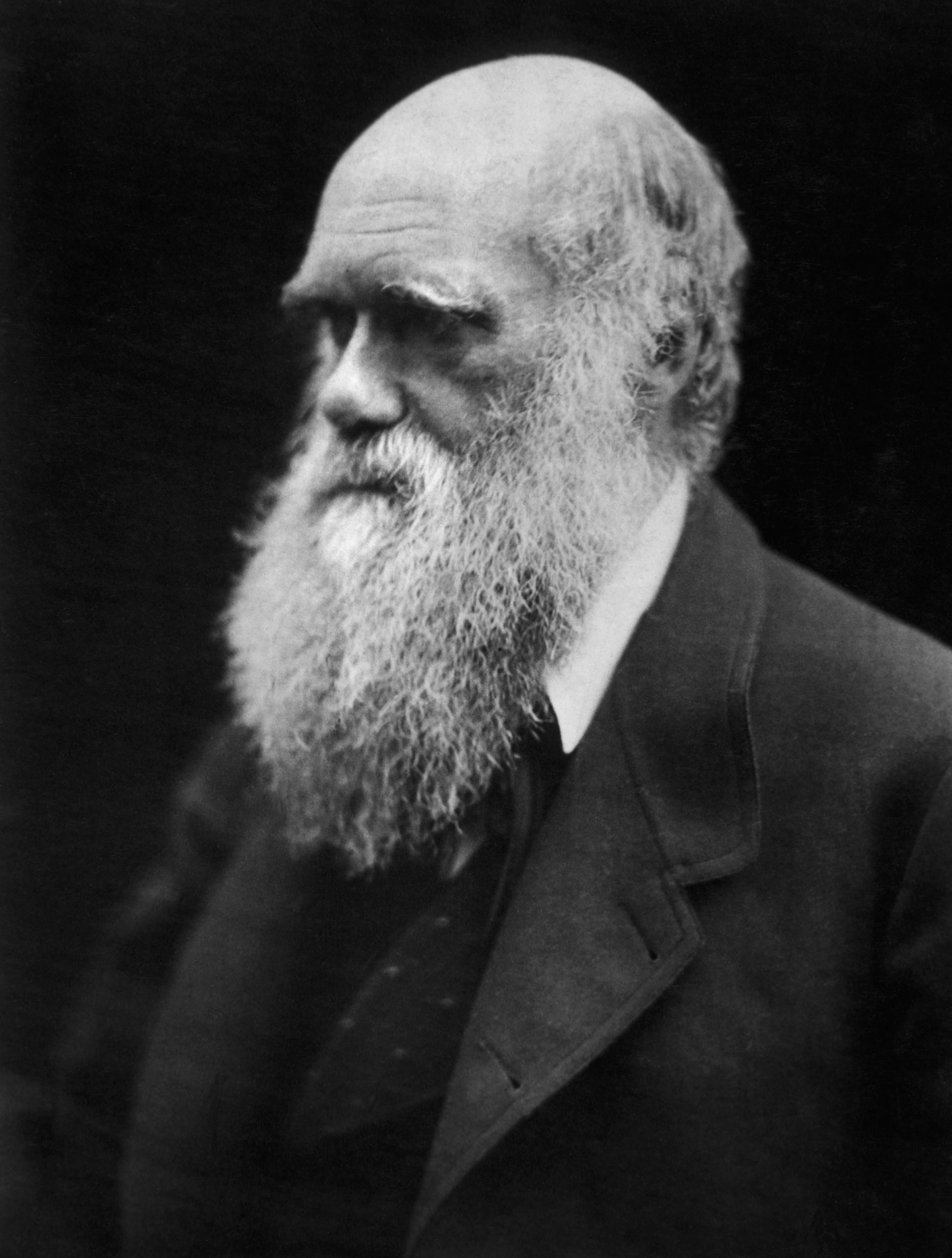

Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) received a camera for her 48th birthday and began taking pictures. Her photographs were inspired by Biblical stories, Greek myth, literature, and Renaissance painting, and she saw photography as high art. Cameron moved in upper-class circles in England, and she photographed friends and intellectuals of the day like the scientists Charles Darwin and Sir John Herschel, a fellow photographer.

Compare and contrast the formal portraits from Nadar’s studio, like that of Selika Laveski above or others, with those of Julia Margaret Cameron. Cameron deliberately blurred the edges of her photographs and emphasized light in order to portray the inner character of the scholars. At the time, she was criticized for the blurriness in her photographs.

Women working in photography in the 19th century usually worked in studios of men. Jobs included breaking and separating eggs for albumen paper (using egg white to give paper a sheen). Women would hand color photographs, work as lab assistants, print cutters, and print mounters for studios producing cartes de visite (calling cards). For women, these jobs were easier to attain because photography was less burdened with social traditions tied to gender roles. In the 19th century, women were still limited in the ways that they were allowed to travel and access public spaces available to men, so their photography was often portraiture.

Stop & Reflect: Women and Photography

- How do social justice movements like the early Women’s Rights Movement (including the campaign for women’s suffrage) and the Civil Rights Movement impact the production and marketing of photography?

- How does photography play a part in the way we understand these movements?

- As you read further here about the significance of documentary photography, continue to consider these questions about the impact of photography on the ways we interpret history.

Focus: Documentary Photography

In addition to portraiture, documentary photography grew as a genre and as a profession. Documentary photography is a straightforward representation chronicling an event or place, person or object. Documentary photography is usually meant to be published and disseminated often with social and political implications.

Frances Benjamin Johnston

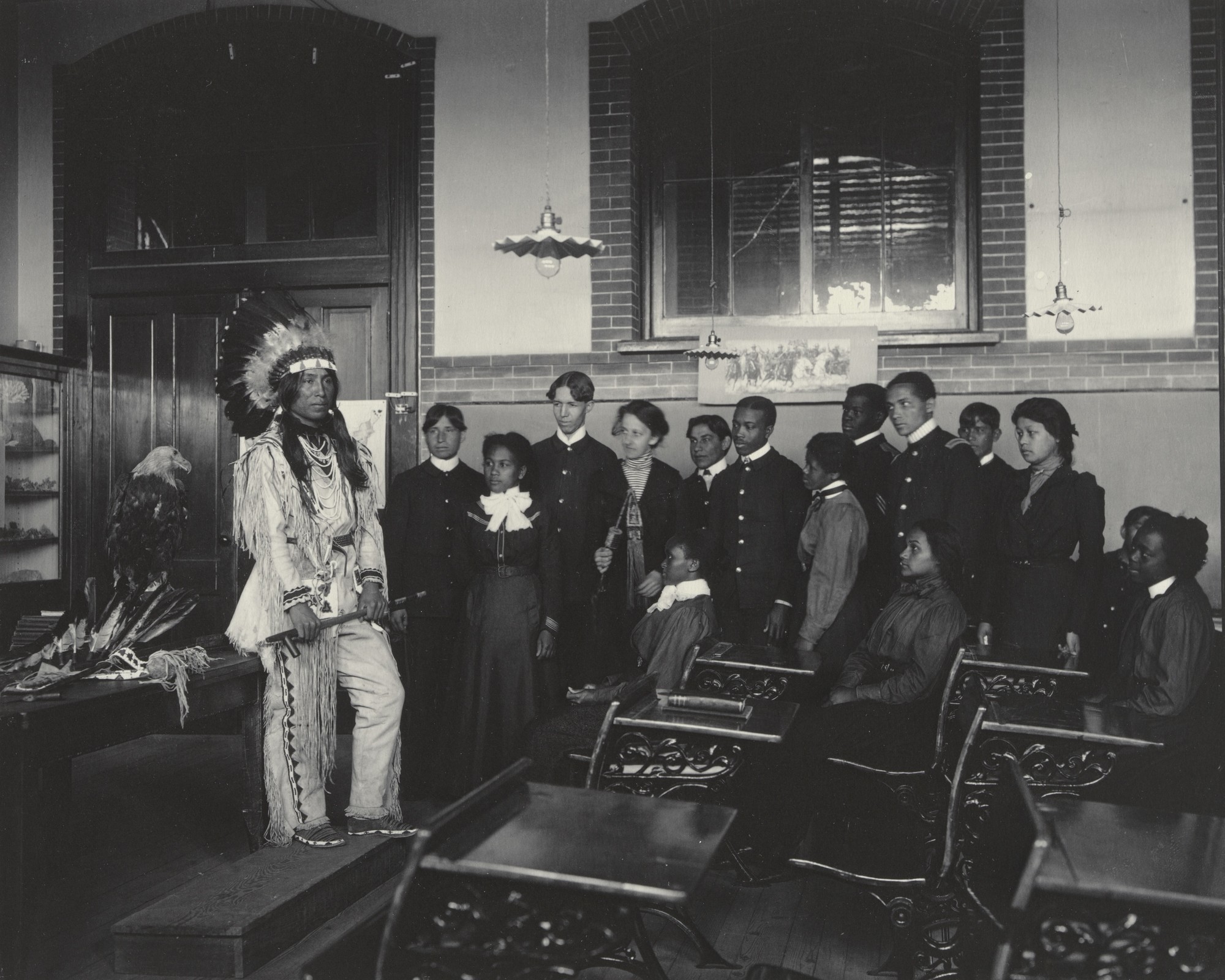

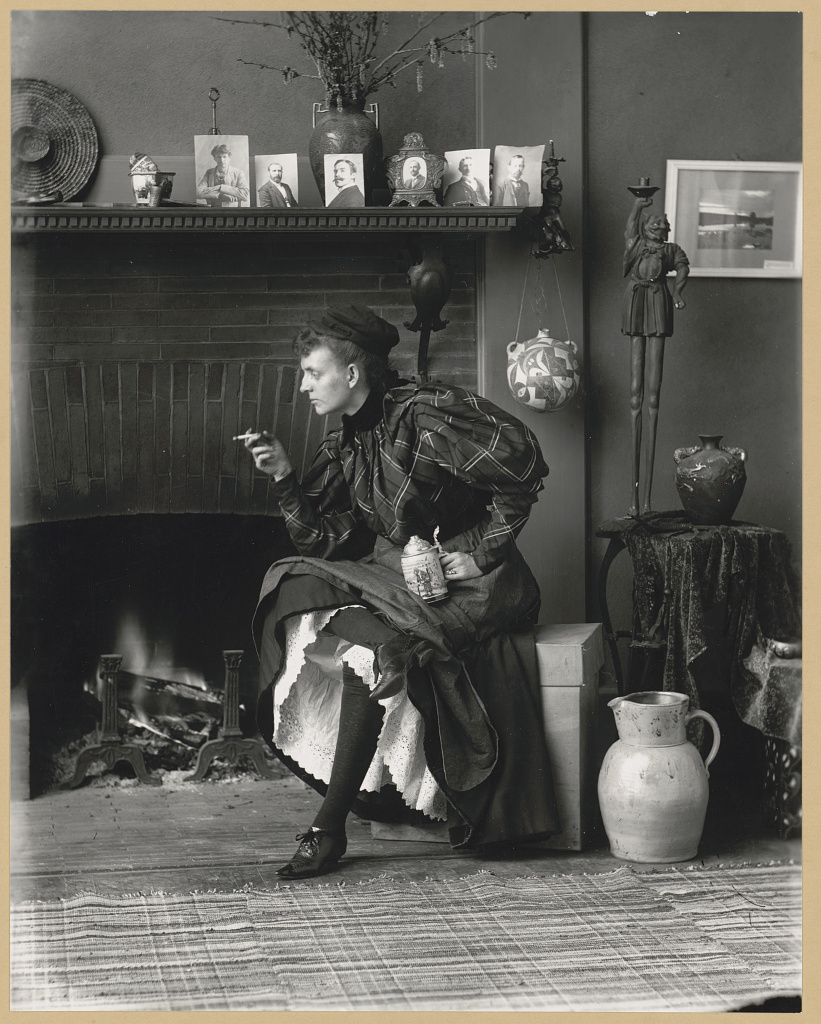

platinum print, 7 1/2″ × 9 1/2″, Museum of Modern Art. Source: Museum of Modern Art, License: Educational Fair Use.

One of the first women documentary photographers in the U.S., Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864-1952) made inroads by running her own photography studio in Washington, D.C. She made portraits, and she took on documentary projects and other media-focused work. In 1899, she was commissioned by Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia to document the school for the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900. Hampton University, as it’s known today, was founded after the Civil War to provide education for freedmen and freedwomen. By the time that Johnston documented the college, it was offering education to Native Americans and African Americans.

Stop & Reflect: Frances Benjamin Johnston

In this self-portrait above, Frances Benjamin Johnston embraces the definition of the New Woman.

- How is Johnston challenging gender roles in the ways that she composes this portrait?

- How does visual analysis direct the way you experience this photograph? Use the key terms introduced in the chapter on visual analysis.

- Compare and contrast Johnston’s self-portrait photograph to the lithographic advertisement for Kodak depicting the “Kodak Girl.” Is one more impactful to you than the other? Explain why.

Matthew Brady, Alexander Garner and Timothy O’Sullivan

Photographic documentation of the Civil War (1860-65) created the most comprehensive visual record of war in history and included images of battlefields and individuals. The compositions continued to be stiff and formal due to the limitations of the camera, like exposure time. However, photographers could process the negatives in the field and send them to be more easily printed and reproduced in cities. Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) worked for Matthew Brady (1822-1896) and went to Civil War battlefields to photograph. He made photographs after the battle at Antietam, Maryland in 1862, photographs very shocking to the public at the time and images that continue to disturb. Photographers on the battlefront sometimes arranged the bodies for a better compositional image as in the image below. The arrangement of bodies creates an implied line that leads your eye back into the landscape. Photographs were often republished as engravings because photographs could not yet be printed at the same time as the text using a printing press.

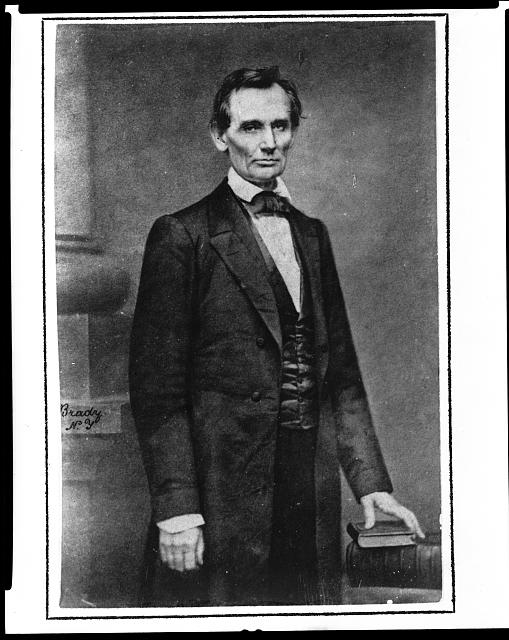

Matthew Brady ran a number of portrait studios on the East Coast and established his reputation by photographing celebrities, including Abraham Lincoln who was running for President. Brady photographed Lincoln on the day of his Cooper Union address. Notice how Brady distracted the viewer from Lincoln’s gangliness by directing him to curve his fingers and by focusing the light on his face. Lincoln credited Brady and this photograph with helping him to win the election.

After the Civil War, the U.S. government sent vast surveys west to document the land. Timothy O’Sullivan (1840-1882) traveled with survey crews of mapmakers and photographed landscapes like the Nevada desert. In contrast to the light sand, the dark cart in this photograph carried water for photographic processing en route.

Dorothea Lange

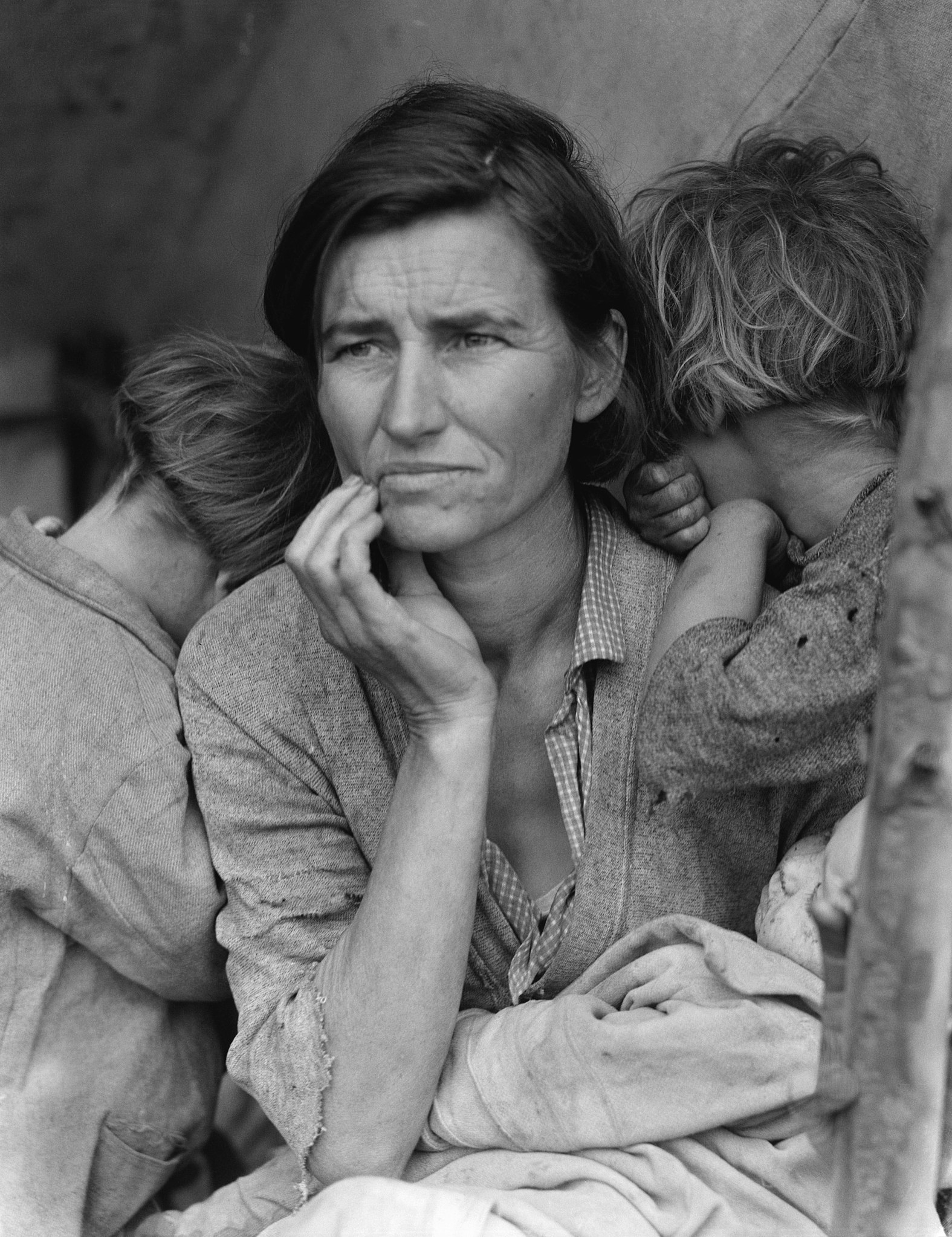

Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) is one of the most iconic documentary photographs. Lange was hired by the Farm Security Administration of the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression to document migrant workers in California.

By cropping out any recognizable background and focusing on the tired woman and three children, Lange pulls the viewer into the composition. The triangular arrangement of the figures gives solidity to the composition that is very reminiscent of historical and biblical images, mostly paintings, of the Madonna and Child.

Focus: Photography and Science

Photography was founded by printmakers and by scientists experimenting with chemicals and their reactions to light. So, it follows that photography early on became a tool for scientific observation and exploration.

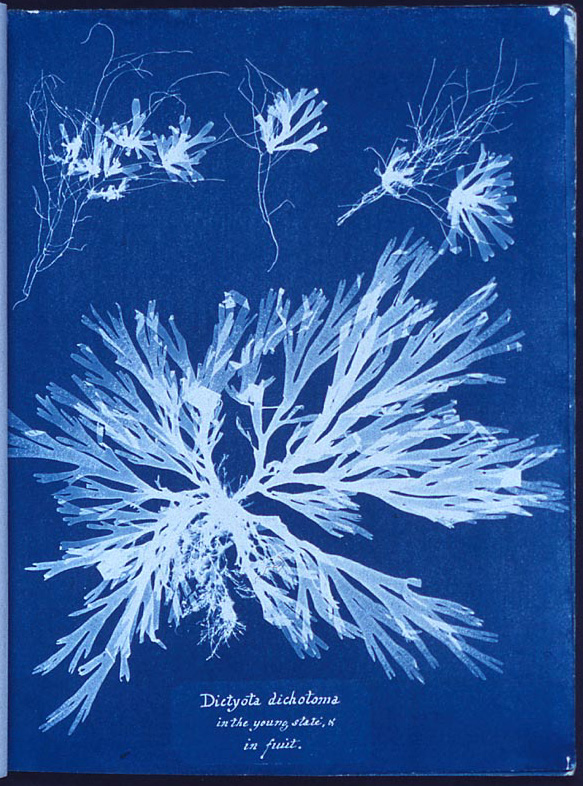

Botanist and photographer Anna Atkins (1799-1871) published photograms of algae in her book Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions in 1843, the first book of photographic images. A photogram is produced by placing objects on light-sensitive paper and exposing it to light.

Focus: Photography and Art

A number of photographers tied their work tightly to fine art and its traditions especially in regards to compositional arrangement and references to historical works of art. Photographers inspired by Modern Art explored and emphasized visual qualities over content or narrative.

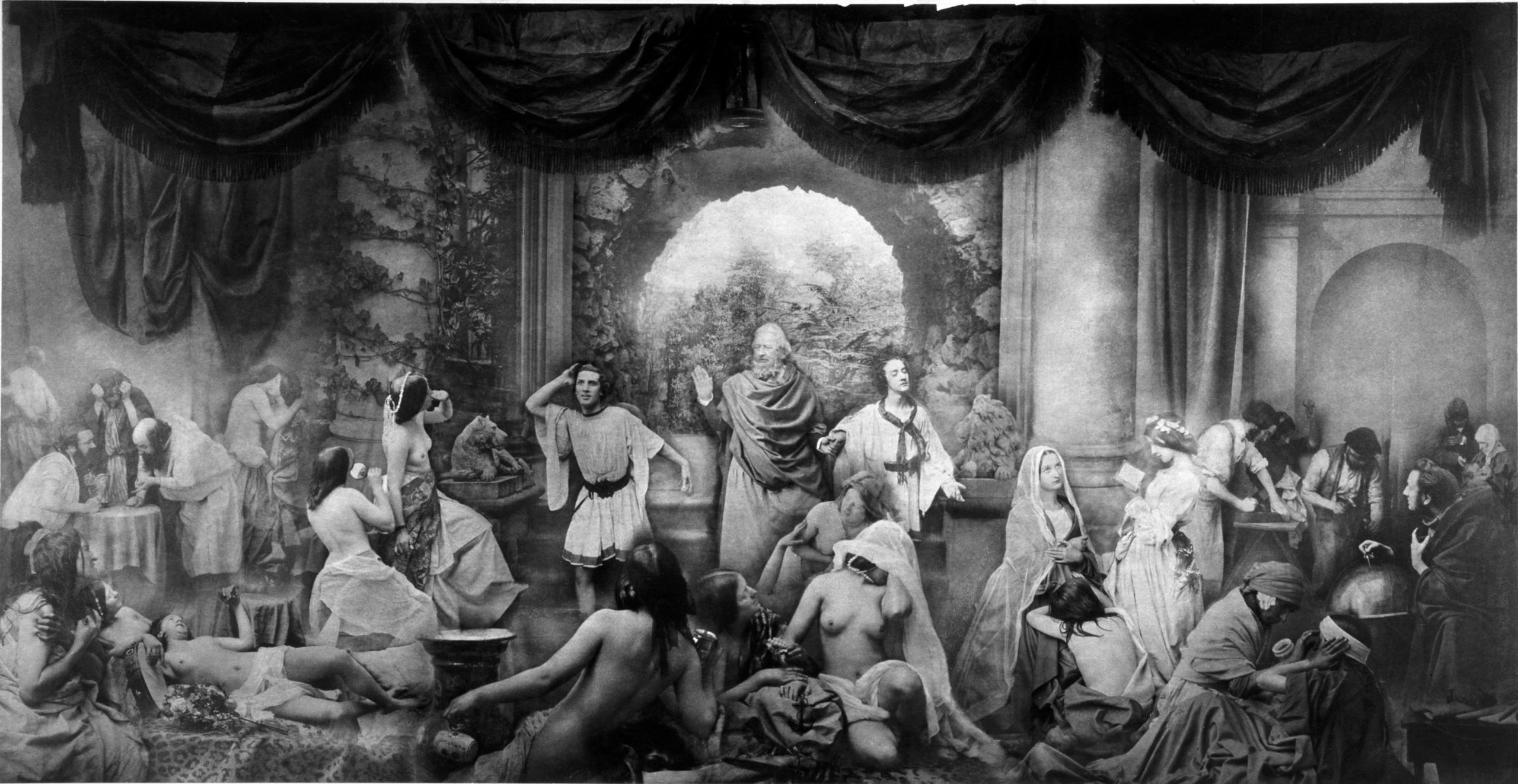

Oscar Rejlander

Oscar Rejlander (1813-1875), who began as a painter copying old masters like Raphael (1483-1520), used photographic processes to produce genre scenes reminiscent of moral, didactic art of the past like Raphael’s Renaissance painting School of Athens.

Two Paths of Life is a “combination print” 31 inches wide and made from over 30 negatives. Rejlander photographed each model individually, and then combined the negatives to produce this composition. Rejlander mostly made portrait photographs, but he saw his works like this to be aligned with painting.

Think about how Two Ways of Life anticipates photo editing of today (like Photoshop).

Alfred Stieglitz and Man Ray

At the turn of the 20th century, Pictorialism was the style in fine art photography. Photographers chose peaceful or sentimental subject matter and photographed with a soft focus, often hand painting the negative or the photograph. In opposition, Alfred Steiglitz (1864-1946) launched the Photo-Secession and called for “straight photography” – a more straightforward depiction of subject matter.

Steiglitz used urban realism as his subject matter and emphasized visual elements in his compositions. In Steerage, he pushed beyond the image of immigrants returning to Europe and considers the shapes (like circles in the hat, the mast), lines (of the gangplank and chains), and the way light draws the viewer’s eyes to the different levels of the ship.

Stieglitz’s contributions include Camera Work, a limited edition magazine on fine paper with photogravure reproductions that was published between 1903 and 1917. He hosted many photography exhibitions at his 291 Gallery in New York City. 291 Gallery was one of the first spaces to exhibit avant garde Modern Art in other media by European and American Modernists.

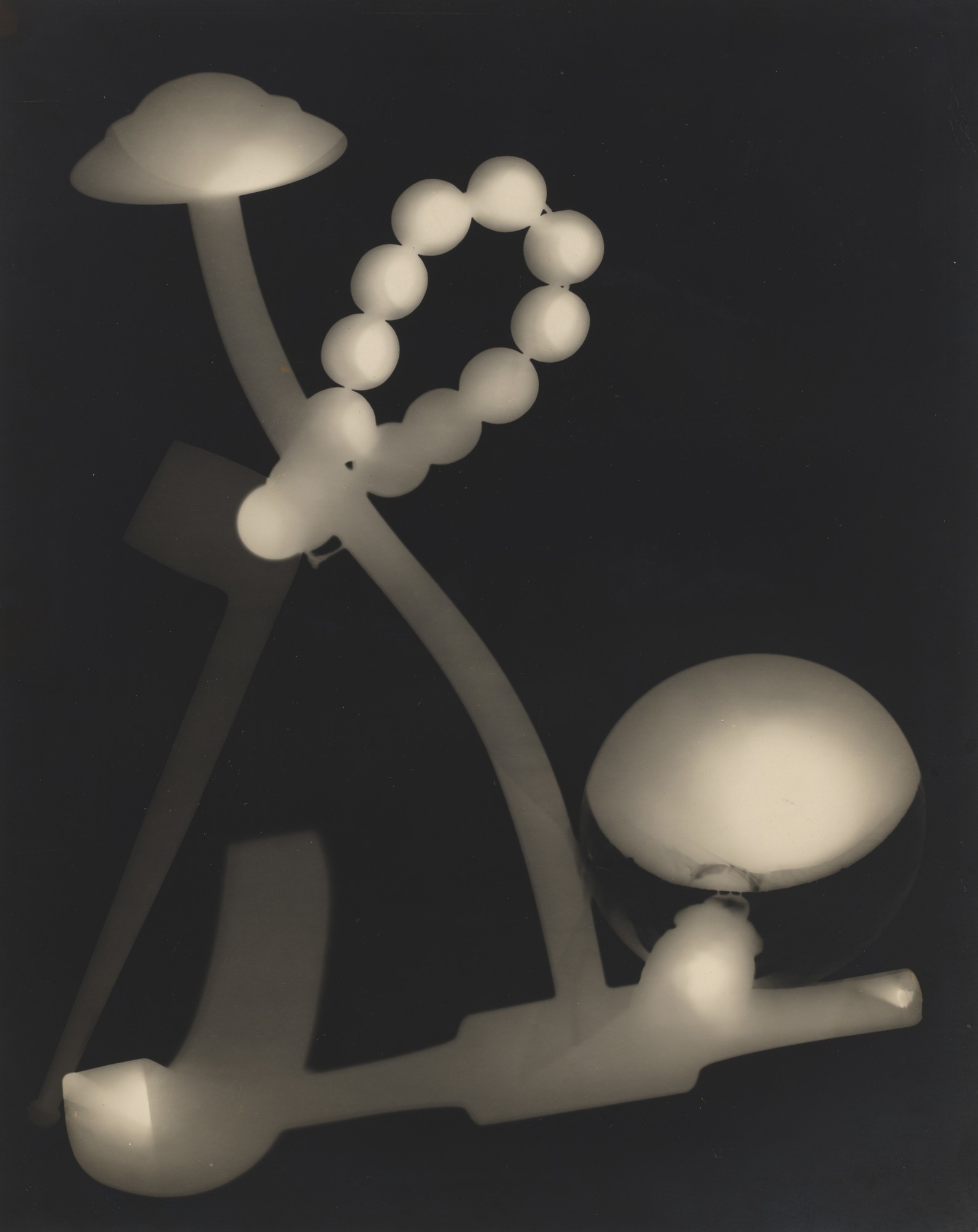

Man Ray (1890-1976) frequented 291 Gallery and was influenced by the Modern Art exhibitions. Man Ray’s photographic work included experiments with photographic processes like solarization. He often cropped and captured his subject matter at unexpected angles. In addition, Man Ray’s cryptic photograms called “rayographs” are associated with themes in Modern Art movements like Dada and Surrealism.

Stop & Reflect: Solarization

- Compare and contrast the photograms of Man Ray and Anna Atkins shown above. Use these works to think about how photography contributes to the disciplines of science and of art.

- Return to the explanation of “the Dada precedent” in the Introduction to New Media Arts. How does photography and Man Ray’s “rayographs” contribute to your understanding of Dada art? How does it reflect qualities of Surrealism?

Focus: Challenging the Flatness of Photography

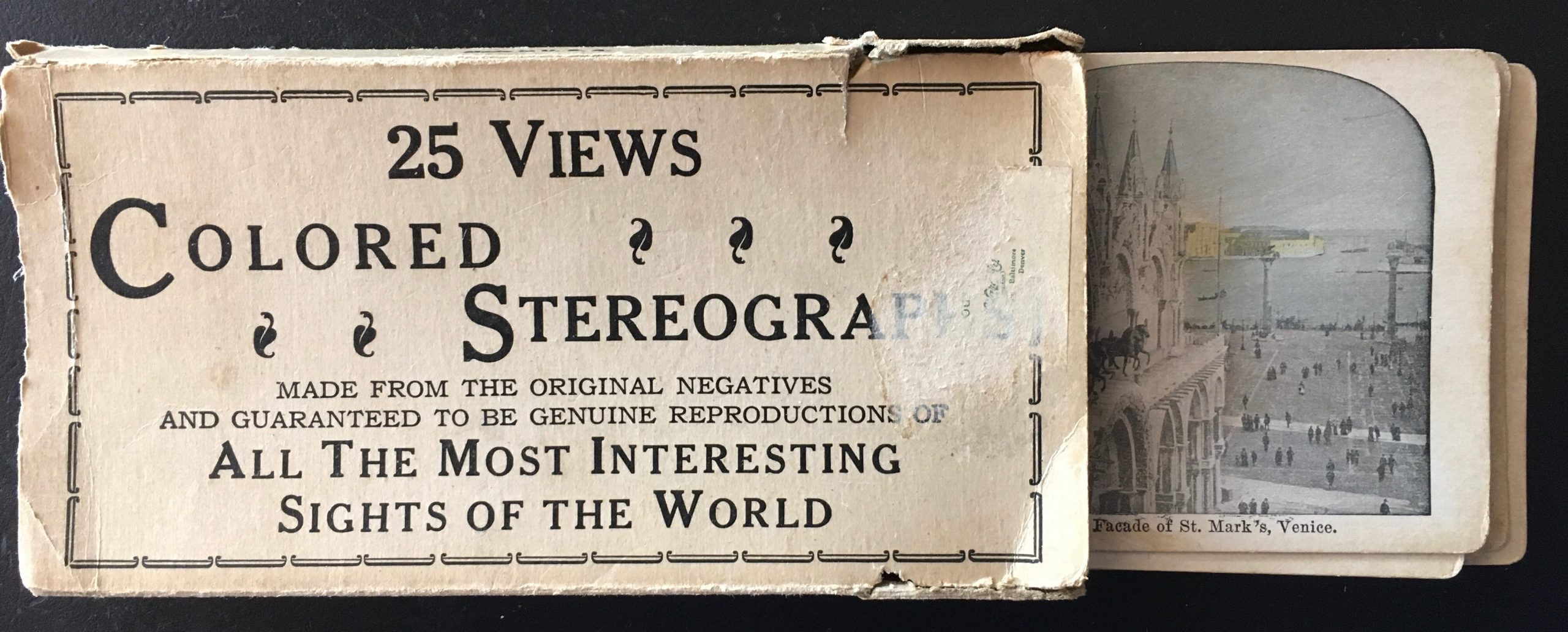

Stereoscope and Stereographs

At the same time as early developments in improving photography, experiments were underway to challenge the two-dimensionality of images. The stereoscope, a viewing device, expanded a viewer’s depth perception and produced a three-dimensional image with receding space by directing each eye to view separate images of the same scene on a stereographic card.

Stereoscopic cameras photographed the same scene with two different lenses about 2 inches apart (about the same distance between the pupils of human eyes).

Stereographs were popular forms of photography from the 1850s to the turn of the 20th century, and they really took off in popularity facilitated by the reproducibility of images with negatives. Millions of stereographs were produced and marketed through mail order catalogues. The subject matter varied from humorous scenes to landscapes to tourist destinations and major monuments, but rarely were portraits published as stereographs. Stereographs were used by painters, for education and for entertainment.

The View-Master is a version of the stereoscope that was introduced in the 1930s and became popular as a child’s toy. These developments in making photographic images in 3D with depth perception anticipate Virtual Reality (VR) of the 21st century. Read about VR in the chapter on Interactivity and Immersive Technology. What connections can you make between VR and the traditions of the stereoscope?

Focus: Challenging the Static Nature of Photography

In the late 19th century, photographers experimented with devices and processes to explore motion. Rather than suggesting movement with a gesture of the figure, they depicted it. You’ll learn more about these experiments in the chapter that focuses on the development of motion pictures and animation.

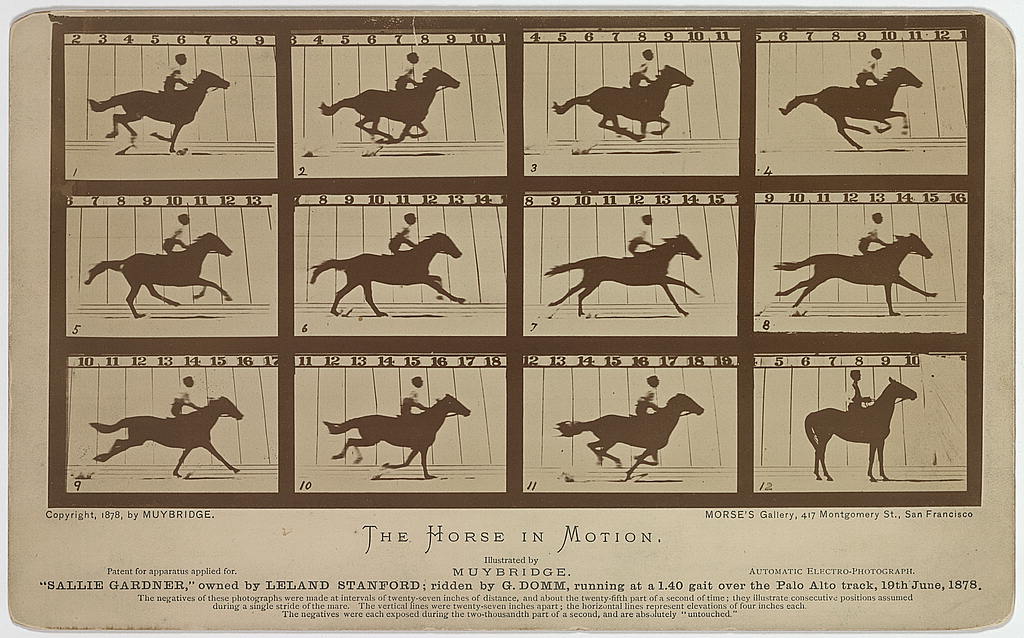

Eadweard Muybridge

Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), studying motion through the use of photography, resolved questions of what we can’t see with the human eye. Muybridge was asked to settle a bet about whether or not all of a horse’s hooves came off the ground while galloping. He lined up multiple cameras along a track and silhouetted the rider against a light background for good contrast in the photographs. The cameras were triggered by strings that stretched across the track. The resulting photographs show some moments in which all hooves are off the ground. What other New Media Art genres do these studies lead to? Look at this animation of the first 11 images of a similar version of this photographic print for a hint.

Muybridge’s studies in human and animal locomotion impacted the history of photography and film and influenced art movements like Futurism in Italy and artists like Duchamp to paint Nude Descending a Staircase, 1912. For further discussion of film, refer to the chapter Early Film and Animation and for further discussion of Modernist art movements also exploring time and motion, please refer to Smarthistory’s Beginner’s Guide to Modernisms.

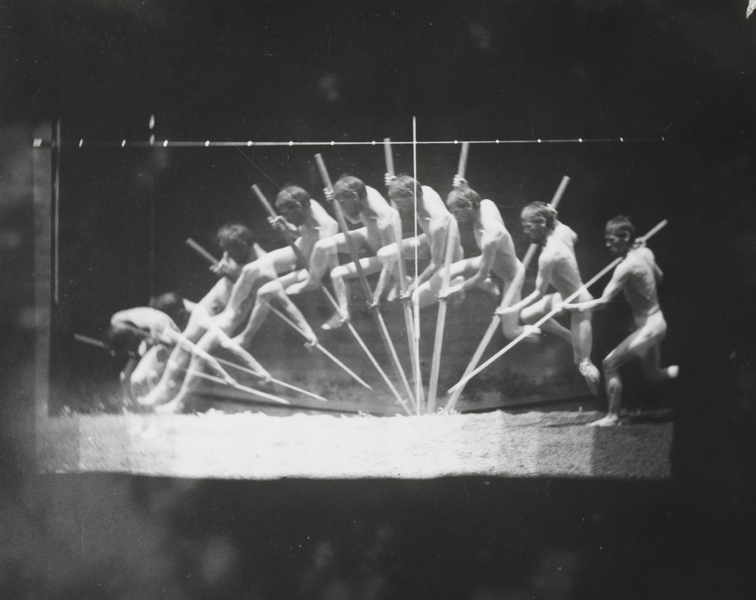

Thomas Eakins

Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), most noted for his paintings and fascination with the human body and biology, also experimented with photography to explore motion. In the motion study of a pole vaulter he used a rotating disc on a single camera to expose a single frame (or plate) multiple times. This process was known as chronophotography. Count how many times you see the figure here, and that is how many times the image was exposed by the rotating disc.

Questions to Consider

- As you continue to read the chapters of this textbook, think about the historical connections to photography through

- processes and techniques,

- visual and experiential qualities, and

- elements of New Media Art.

For example, explain the threads to photography that you find in

- Read about the Modern Art movements of Dada and Futurism in

How has photography impacted these Modern Art movements? Think about changes in processes and techniques, subject matter, and visual and experiential qualities. Tie this to Elements of New Media Art.

Conclusion: Beyond Analog

This chapter has introduced you to the foundations of photography in the 19th century and early 20th century. It isn’t until the early 20th century that we see digital photography explode with the ubiquity of mobile phones with cameras. See what historical threads are continued (and are broken) as you read about contemporary photography and explorations with digital cameras and processes in the next chapter, Digital Photography.

Key Takeaways

At the end of this chapter you will begin to:

- Explain the history of photography.

- Consider how photography impacted global cultures when it was introduced.

- Describe and compare significant photographic processes.

- Explain how photography relates to the elements of New Media Art.

Selected Bibliography

Cramer, Dr. Charles and Dr. Kim Grant. “Surrealist Photography.” Smarthistory, April 8, 2020, accessed August 30, 2021. https://smarthistory.org/surrealist-photography/.

“A Durable Memento: Portraits by Augustus Washington, African American Daguerreotypist,” September 24, 1999 – January 2, 2000 exhibition. National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://npg.si.edu/exh/awash/index.htm

Easby, Dr. Rebecca Jeffrey. “Early Photography: Niépce, Talbot and Muybridge.” Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed August 30, 2021. http://smarthistory.org/early-photography-niepce-talbot-and-muybridge/.

Easby, Dr. Rebecca Jeffrey. “Julia Margaret Cameron, Mrs. Herbert Duckworth.” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed August 30, 2021. https://smarthistory.org/julia-margaret-cameron-mrs-herbert-duckworth/.

Easby, Dr. Rebecca Jeffrey. “Louis Daguerre, Paris Boulevard.” Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed August 30, 2021. https://smarthistory.org/daguerre-paris-boulevard/.

Easby, Dr. Rebecca Jeffrey. “Timothy O’Sullivan, Ancient Ruins in the Cañon de Chelle.” Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed August 30, 2021. https://smarthistory.org/timothy-osullivan-ancient-ruins-in-the-canon-de-chelle/.

Gaylord, Kristen. “Frances Benjamin Johnston,” Museum of Modern Art, 2016. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.moma.org/artists/7851

Harris, Leila Anne. “Lady Clementina Hawarden, Clementina and Florence Elizabeth Maude.” Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed August 30, 2021. https://smarthistory.org/lady-clementina-hawarden-clementina-and-florence-elizabeth-maude/.

The Museum of Modern Art. “A Closer Look at Frances Benjamin Johnston. The Hampton Album 1899-1900.” Seeing Through Photographs online course, February 13, 2019. YouTube video, runtime 1:47. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://youtu.be/BUFiV6moRPI

Talbot, William Henry Fox. The Pencil of Nature. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1844. Read online at or download from the Project Guttenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/33447

Thompson, Clive. “Stereographs Were the Original Virtual Reality.” Smithsonian Magazine, October 2017. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/sterographs-original-virtual-reality-180964771/