12 Performance Art

An Art of Action

This chapter focuses on performance from the 1960s to today. Like their avant-garde predecessors, discussed in the Introduction to New Media Art chapter, the performance artists examined here create work that redefines traditional art-making practices. Frequently relying on direct audience interaction and participation, modern and contemporary performance artists explore the body, examine process, and further break down boundaries between art and life. Performance, as we’ll see, is also time-based and ephemeral, often captured and made “permanent” through photography, film, and video. After watching and reading some background information, the examples throughout this chapter are presented as thematic case studies.

Watch & Consider: The Case for Performance Art

For a brief historical overview discussing the significance of performance art, please watch the primer, embedded below, from PBS Studio’s The Art Assignment, “The Case for Performance Art” (9:09 minutes).

Read & Reflect: Performance Art

The reading from Smarthistory, linked to below, focuses on how performance artists seek to locate new forms of expression as alternatives to traditional media. It also discussed the importance of the viewer and places performance in historical context.

- “Performance Art: An Introduction” (Smarthistory)

The Basics: What is Performance Art?

As we’ve seen in previous chapters, non-traditional art-making materials and methods, like dance and music, have been used by artists since the early 20th century. In fact, performance art has its roots in early 20th century avant-garde movements such as Dada and Futurism. Dada performances, such as Hugo Ball’s (1866-1927) recitation of Karawane at the Cabaret-Voltaire, demonstrate an interest in incorporating non-traditional art-making materials and methods into performance art, as well as the enduring quality of ephemerality.

Italian Futurists also used performance to express their dissatisfaction with the status quo, staging disruptive performances called serata, which reconfigured the artist as a confrontational performer in the public sphere. These evenings incited audience participation and interaction, often even ending in brawls.

Despite their extreme ideological differences, both Dada and Futurist artists were concerned with making art that interacted, at times viscerally, with life, rather than in creating a lasting art object removed from the messiness of living, meant for veneration on a museum’s walls. We can still see the influence of these movements in performance today.

In the United States, performance art emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, against the backdrop of war (in Korea and Vietnam), developing social and racial justice movements for civil rights and equality, and technological advancements, such as the television.

Using their body as medium, performance artists question the definition of art, explore the role of art in society, and critique how art is valued. Through the often intermedia qualities of their works, performance artists also consider how traditional concepts of art (e.g., painting or sculpture) can be given renewed relevance through new technologies.

Perhaps because it confronts the viewer, takes place in real time, and uses the artist’s own body as medium, performance has, historically, occupied a less privileged place in art history than conventional media. As you review the works featured in this chapter, watch for instances of intermedia, a critical cross-disciplinary strategy of New Media artists that encourages mixing materials and embraces new technologies.

A Two-Way Exchange: Audience & Performance Art

As mentioned above, performance artists are interested in breaking down boundaries between art and life, creating a new context for a work of art. What barriers exist between art and life? First, think of where you would traditionally view a work of art. You might have thought about the museum or gallery space as a primary venue for seeing art. While performance can (and does) exist in the museum or gallery space, historically performance artists sought to present work outside of traditional art-viewing venues. They did this both to engage more directly with the viewer in the public space and to separate their work from the value systems imposed by the art world.

Performance artists also blur the boundaries between art and life by using everyday, or non-art, materials in their works. In this chapter, you’ll examine performances by artists who use meat, dirt, snow, and their own clothes, among other non-art materials, in their works.

We’ve already learned about Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) in the context of Dada. Duchamp argued that both the artist and the viewer are necessary to complete a work of art. In “The Creative Act” (1957), Duchamp said, “All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualification and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.”

Let’s think about this quote for a minute. How do you interpret Duchamp’s statement? You might consider how Duchamp’s words attempt to dissolve the distance between artist and viewer, or spectator. If the viewer is responsible for bringing “the work in contact with the external world” then they are necessary to complete the work of art. This helps equalize the relationship between artist and audience and encourages a more active role for the viewer.

Questions to Consider: Performance Art

As we move through the examples presented in this chapter, let’s consider the following questions:

- How does performance continue to shift the relationship between artist and viewer? Can you think of ways performance helps reinvent this relationship?

- How does soliciting active involvement from the viewer challenge their historically more passive role? How does direct viewer participation break down traditional or conventional barriers between artists, the artwork, and the viewer?

- Finally, when artists engage and collaborate with audiences to create or complete a work of art, do you think it’s hard for them to relinquish some control over the work’s outcome? Why or why not?

Additionally, throughout the chapter, look for examples where artists:

- Perform and present work outside the traditional venues (e.g., museums or galleries),

- Engage the audience directly, or

- Use everyday (non-art) materials.

Key Terms

These terms are presented in bold throughout the chapter. When you encounter one, be sure to note the definition. You may see these terms used elsewhere in the textbook; here they are discussed in the context of performance art, specifically.

- Behavior Art (associated with Tania Bruguera)

- Body Art

- Collaboration

- Conceptual Art

- Durational Performance

- Ephemeral

- Event

- Fluxus

- Happenings (associated with Allan Kaprow)

- Intermedia

- Kinetic Theater

- Participatory

- Performalist Self-Portraits (associated with Hannah Wilke)

- Score

- Social Body

- Street Action (associated with David Hammons)

Performance Artists & Artworks

As we’ll see through the example discussed in this chapter, performance art is diverse and often interdisciplinary. As you review each work, keep in mind that performance is defined by an individual work of art, rather than by an artist’s entire career. In other words, someone who sculpts or paints can also create a performance, and an artist who makes a performance can also be a sculptor. What these pieces have in common is that they are centered on an action carried out, or arranged, by an artist. They are also time-based and ephemeral, rather than permanent artistic gesture with a specific beginning and an end. Since we are viewing these works now as photographs or videos, you can see how documentation of the performance might live on forever, but the performance itself is a fleeting moment in time.

Focus: 1960s: The Impact of Fluxus

The early examples of performance discussed in this first section are connected to Fluxus. As you learned in the introduction, Fluxus is an international art movement led by George Maciunas (1931-1978) that emphasizes chance, the unity of art and life, and the ephemeral moment. Without a single defining style, Fluxus sought to democratize art and art-making by creating event scores to be enacted by anyone. An event refers to a Fluxus performance, while a score is the set of directions the Fluxus performer follows and interprets. Fluxus events were anti-commercial as they were not intended to result in an object that could be purchased or collected. Collaboration and intermedia methods were encouraged in order to create art that was directly participatory.

While all four artists discussed in this section, Yoko Ono, Carolee Schneemann, Alison Knowles, and Benjamin Patterson, have a connection to Fluxus early in their careers, Ono and Schneemann distanced themselves from the movement (Schneemann after Meat Joy, specifically).

Elements of New Media Art

As you review the examples discussed below, think about how each illustrates specific qualities of a Fluxus art. Also, consider how performance in general connects to New Media art. You might reflect on how performance:

- Dismantles the boundaries between art and life.

- Employs chance.

- Engages the viewer as a participant.

- Focuses on the process or the act of creating, not the outcome.

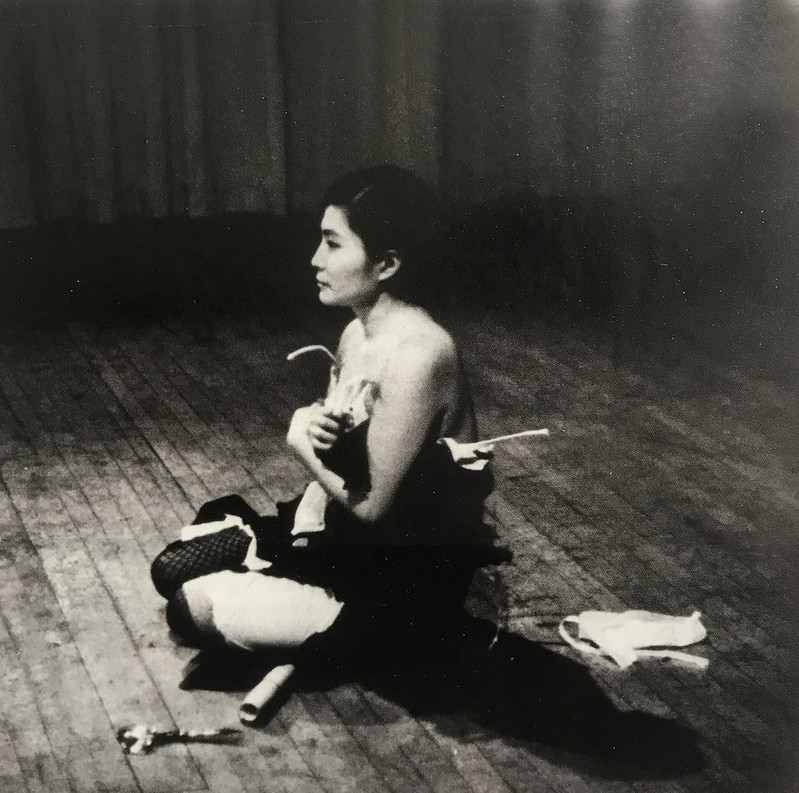

Yoko Ono, Cut Piece, 1964

The Japanese artist Yoko Ono (born 1933) debuted Cut Piece in Kyoto, Japan, in 1964, and has since performed it in Tokyo, New York, London, and Paris. The performance is the realization of a score, or a set of participatory instructions that result in the creation of the Fluxus event. A member of the Fluxus movement, Yoko Ono’s work challenges the viewer to become an active participant in the performance by asking them to cut off pieces of her clothing, as she sits motionless on the stage.

Read Yoko Ono’s score for Cut Piece:

“Cut Piece First version for single performer: Performer sits on stage with a pair of scissors in front of him. It is announced that members of the audience may come on stage—one at a time—to cut a small piece of the performer’s clothing to take with them. Performer remains motionless throughout the piece. Piece ends at the performer’s option.”

In a second version, Ono amended the instructions slightly, indicating that, “members of the audience may cut each other’s clothing. The audience may cut as long as they wish.”

(The above score is excerpted from MoMA’s website, quoted from Kevin Concannon, “Yoko Ono’s CUT PIECE: From Text to Performance and Back Again,” Imagine Peace.)

Watch & Reflect: Cut Piece

Watch this excerpt from Yoko Ono’s performance of Cut Piece:

Questions to Consider:

- What do you notice about the performance? Where is the artist? Where is the audience? What role does the audience assume in this work? How is Yoko Ono’s score reflected in the actions of the performance?

- Read this excerpt from a MoMA audio guide where Ono reflects on her experience performing Cut Piece.

- How does Ono’s piece reflect Fluxus ideology?

- After learning more about Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece, how do you think you would have experienced her work as a viewer? Would you have participated in the event? Why or why not?

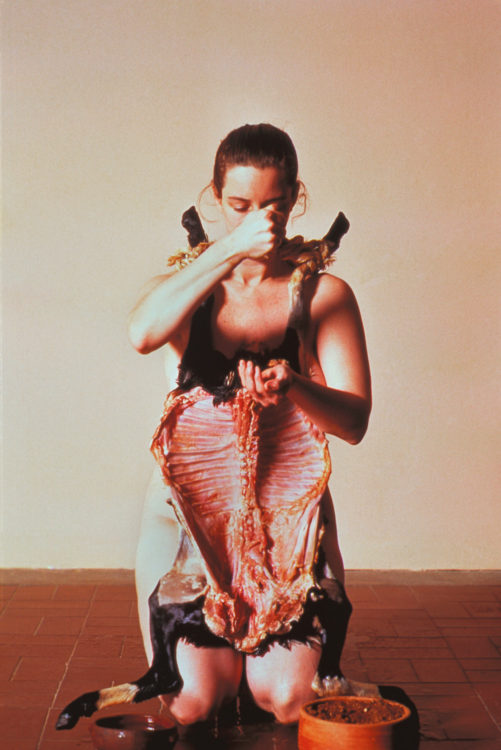

Carolee Schneemann, Meat Joy, 1964 (re-edited 2010)

Carolee Schneemann (1939-2019) was an American multidisciplinary artist and an incredibly important figure in performance and feminist art. She is known for her explorations of gender, sexuality, and sexism in art history, through work that encompasses painting, performance, film, installation, and video art.

In Meat Joy, a group of dancers (including Schneemann) wear feather-lined bikinis and briefs, as they move in both choreographed and spontaneous ways atop a plastic sheet. They rub raw fish, chicken, and sausages over their bodies, and cover themselves in wet paint and scraps of paper. The result is a tactile experience and an honoring of flesh in many forms. Though not directly participatory, the audience could see the movement and hear the sounds of the dancer’s bodies, and smell the mixing of meat, paper, and paint. Later, Schneemann pieced together bits of footage from various performances of Meat Joy and set it to music with a voice-over, adding yet another sensory layer.

In More Than Meat Joy, Schneenmann writes of the performance:

The focus is never on the self, but on the materials, gestures & actions which involve us. Sense that we become what we see, what we touch. A certain tenderness (empathy) is pervasive – even to the most violent actions: say, cutting, chopping, throwing chickens. (Schneemann, 253).

Schneemann referred to her work as kinetic theater because it creates “an immediate, sensuous environment on which a shifting scale of tactile, plastic, physical encounters can be realized. The nature of these encounters exposes and frees us from a range of aesthetic and cultural conventions” (Youngblood, 366). As Schneemann describes, kinetic theater fosters an intermedia experience between dance and performance where touch and physicality are explored and celebrated in various forms. Kinetic theater relates to Fluxus because of the way the body is staged in a social space. Even though this performance is not directly participatory, we can consider the ways in which it embraces the use of everyday, non-art materials and creates a sense of immediacy and intimacy.

After viewing Meat Joy and reading Schneemann’s statement about her work, consider its historical context. First performed in Paris in 1964, and then later that same year in London and New York, we might think about Schneemann’s performance as an act of resistance. In 1964, the Vietnam War is raging and Black Americans, women, and people with disabilities are fighting for equal rights (the Civil Rights Act has only just been signed into law in 1964). By choreographing a piece that openly and publicly explores the body as a site for both sensuality and violence, Schneemann creates a performance that transgresses societal norms.

Stop & Reflect: Meat Joy

Watch Carolee Schneemann’s Meat Joy, 1964 (re-edited 2010), filmed performance, 10:33 minutes, color, sound, 16 mm film on video (you will have to click through to view on YouTube). You can also listen to Carolee Schneemann discuss the sensuality of Meat Joy (2:00 minutes).

Questions to Consider:

- What materials does Meat Joy use? How is this work an example of an intermedia approach?

- Can you think of ways Schneemann’s performance rejects the traditional “dismissive” approach to female sexuality prevalent in western art history?

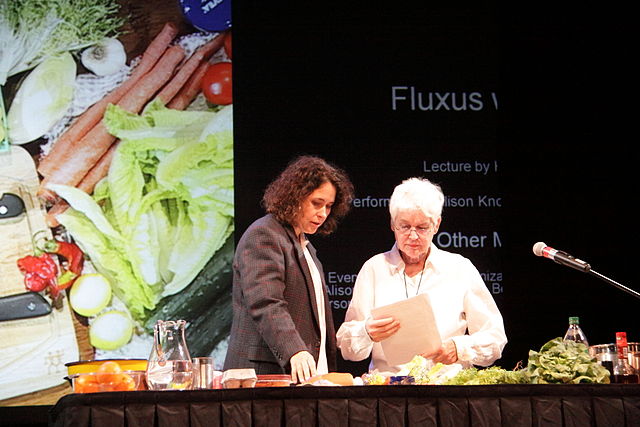

Alison Knowles, Make a Salad, 1962

Alison Knowles (born 1933) is an American artist and a founding member of Fluxus. She is known for her use of ordinary, non-art materials, and scores that celebrate the everyday. In Make a Salad the participants are instructed via a Fluxus score to….make a salad! The process of making the salad, from selecting the ingredients, to mixing in the dressing, to serving it, will vary. The salad you make will be your salad and will be entirely dependent on what you have on hand and how you interpret the score.

The piece also has a vital auditory component: close your eyes and imagine the noise made by the chopping of vegetables and the rustling of lettuce leaves. What sound does the bowl make as you mix your ingredients together? What about when you bite down on a piece of lettuce or a cucumber? This is considered music, as if one was listening to actual instruments performing a symphony. This idea of the “in-between” moments of everyday life being as important as a set of carefully composed notes has its roots in the scores of the American avant-garde composer John Cage (1912-1992), whose work inspired many Fluxus artists, though he was never a member of the group.

Stop & Reflect: Make a Salad

First, to see this work and the process in action, watch Alison Knowles – ‘I’m Making a Giant Salad’ | TateShots about Knowles’ 2008 event at the Tate in London (3:47 minutes):

Then, for additional context, watch this video of Knowles discussing Fluxus more broadly, Alison Knowles: Fluxus Event Scores (2:57 minutes):

Questions to Consider:

- How does Knowles involve the viewer as participants in her event?

- In 2008, Knowles performed this piece in front of a large audience at the Tate; how would this work be different if you performed it at home? How would it remain the same?

- What other everyday moments could be celebrated through a score? What would you perform?

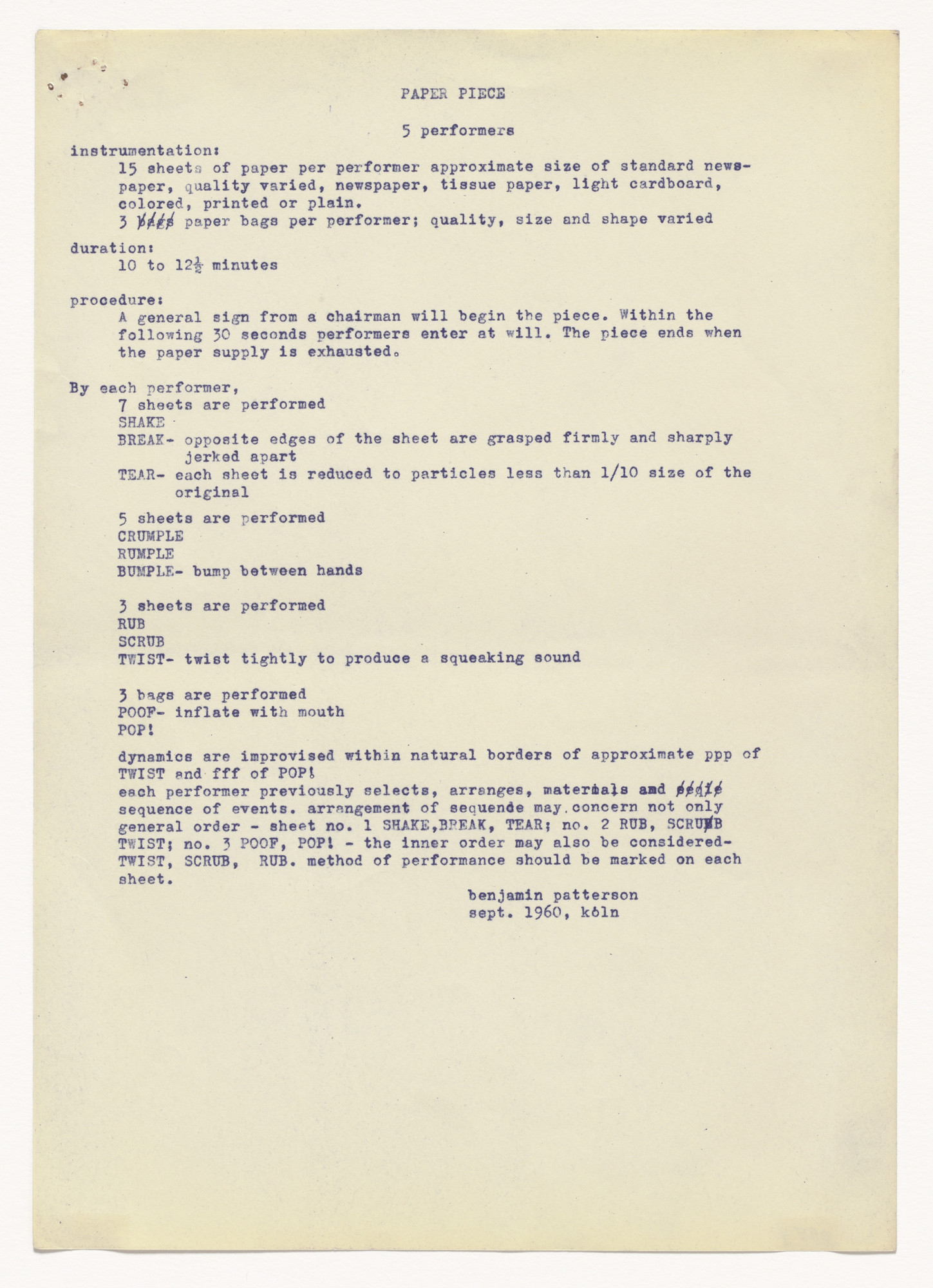

Benjamin Patterson, Paper Piece, 1960

A founding member of Fluxus, Benjamin Patterson (1934-2016) was a classically trained double bassist who connected his experimental musical scores with audience participation to create what he called compositions for actions. Interested in the democratization of art and music, Patterson’s focus on indeterminacy was influenced by a meeting (and, later, a performance) with John Cage in 1960, while both composers were in Cologne, Germany. The first version of Patterson’s Paper Piece, was actually part of letter he mailed home to his parent a Christmas present to them, since he wouldn’t be home to celebrate.

A joyful celebration of everyday movements and sound, Paper Piece asked the audience to “crumple,” “rumple,” and “bumple” sheets of paper. See the video below of the Ensemble for Experimental Music and Theatre performing Patterson’s score in 2013 (YouTube, 9:58 minutes):

Stop & Reflect: Fluxus

- What are some ways you would describe a Fluxus Event Score?

- What are some differences between attending a traditional play in a theater vs. participating in a Fluxus Event Score?

- In what ways do Fluxus Event Scores challenge traditional ways of viewing art in a gallery?

- How do Event Scores expand what it means to be an audience member or viewer?

- How do Event Scores pieces expand what it means to be an artist?

- In what ways does Fluxus blur the lines between art and life? Fluxus Event Scores are different than other approaches to Performance Art discussed below. Consider some of these differences as you continue to work through this chapter.

Focus: 1970s: Body Art

Optional Video: Can My Body be Art? How Art Became Active (Tate, 4:05 minutes)

Body Art is a type of performance that developed in the 1960s and 1970s. As its name implies, Body Art uses the body, usually but not always the artist’s, as a basis for the artwork. Endurance is often central to Body Art, such in the examples by Chris Burden and Hannah Wilke discussed below. Body Art can also negotiate issues of identity, gender, and sexuality. Ana Mendieta’s work, for example, explores feelings of displacement related to her identity as an exiled Cuban artist living in the United States. It’s important to note that Carolee Schneemann’s work, discussed in the previous section, is also considered Body Art; remember that, especially in New Media, boundaries are fluid and artworks will belong to more than one category.

Chris Burden, Shoot, 1971

The American artist, Chris Burden (1946-2015), performed Shoot at a Santa Ana, CA gallery called F Spot in 1971; the artist was 25 years old. Standing in front of a small audience of mostly friends, Burden’s friend shot him with a .22 long rifle from a distance of 13 feet. The bullet, meant to graze Burden’s arm, actually hit him, causing the artist to be taken to the hospital. You can see still images from the performance at Media Art Net.

This work is an example of Body Art. As discussed above, Body Art is a type of performance that explicitly uses the body, often pushed to its extremes, to address the relationship of the body to society. Shoot, like many examples of Body Art is transgressive, meaning it pushes the boundaries of what’s comfortable or acceptable (this also applies to Meat Joy). In Burden’s work, he engages in an acute action in order to shock the viewers, forcing them into an immediate, emotional response.

Staged when the United States was embroiled in the controversial Vietnam War (1955-1975), Burden’s performance can be interpreted as a way to process images of violence seen by many on the nightly news during this “televised” war.

Stop & Reflect: Shoot

Watch: “Shot in the Name of Art” (Op Docs, the New York Times via YouTube, 4:39 minutes)

Content Warning: A person being shot with a gun.

- How does Shoot comment on the public’s growing desensitization to violence?

- Does the viewer of a violent act become complicit in the artist putting his body at risk?

- Can you compare and contrast Burden’s use of his body with one other artist discussed in this chapter?

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Blood Sign #2/Body Tracks), 1974

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Blood Sign #2/Body Tracks), 1974, performance on video (1:20 minutes); clip is 1:13. See a video still and read about Mendieta’s performance at the Reina Sophia Museum website.

Ana Mendieta (1948-1985) was a Cuban-born cross-disciplinary artist living in exile in the United States. Forced to leave Cuba when she was just 12 years old, due to her father’s involvement with a counterrevolutionary group, Mendieta and her sister were separated from her mother and younger brother, and sent to live in Iowa via Operation Pedro Pan. She would not reunite with her whole family for another 18 years.

In much of her practice, Mendieta used her body to address a sense of dislocation and express the trauma of violence against women. In Untitled (Blood Sign #2/Body Tracks) we watch as the artist, dressed in white and cream, approaches a white wall. She raises her arms, placing them against the wall. She then begins to kneel, slowly dragging her arms down the wall. Mendieta rises and walks out of the frame, leaving behind two red lines, marks made by her forearms, which were covered with animal blood.

The lines create a shape reminiscent of a tree trunk and serve as a reminder of the ephemerality of the artist’s body, which is no longer present. Untitled (Blood Sign #2/Body Tracks) also ties into Mendieta’s Silueta series (1973-1978) in which the artist photographs and films her body, both its presence and absence, in nature.

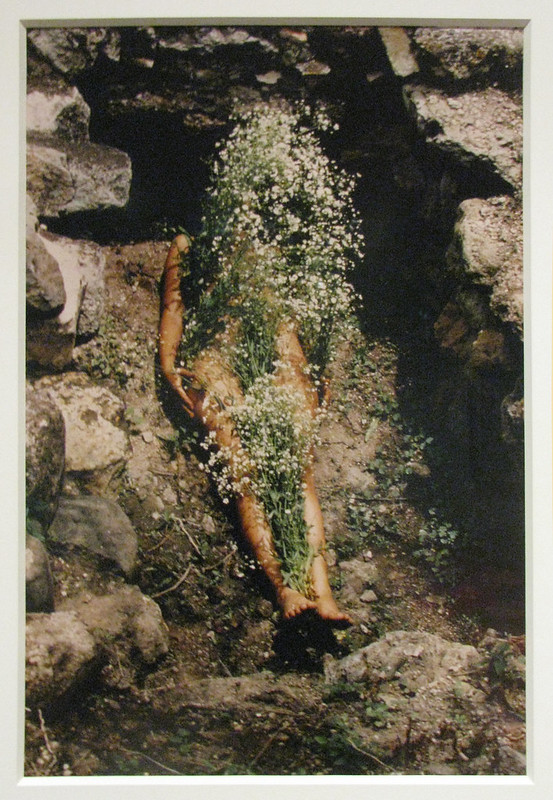

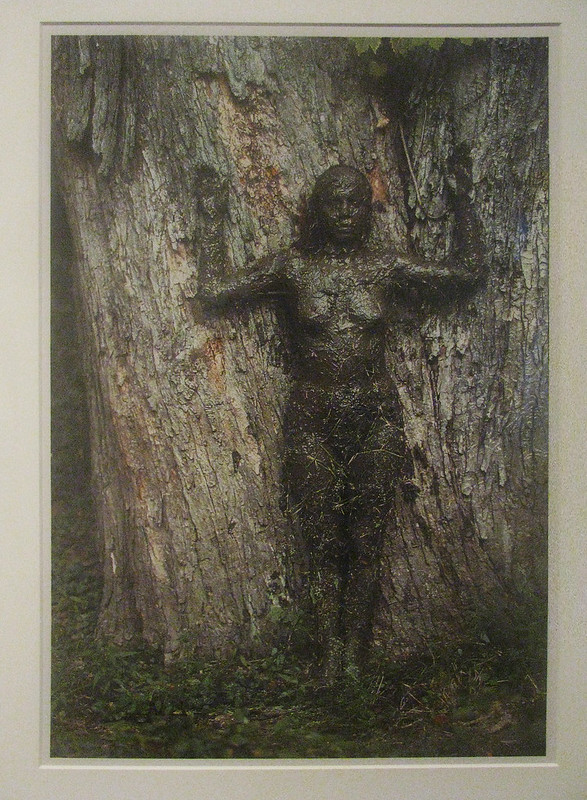

Ana Mendieta, Silueta, 1973-1978

Mendieta began work on the Silueta series in 1973 while on a trip to Oaxaca, Mexico, with her classmates in the Intermedia program at the University of Iowa and their instructor, Hans Breder. Mendieta was fascinated by Mexico, in part because the country reminded her of Cuba, and she continued the series when she returned to Iowa. The photographs and films she took serve to document her performances in the land and are a type of performance that Mendieta called earth-body works. These works align Mendieta with both performance, land, and feminist art.

In one Silueta, pictured above, we see a photograph of Mendieta laying naked in a Zapotec tomb. White flowers lay over her body, obscuring it. The flowers seem to grow from her, connecting her visually and symbolically with the land. We might think of the cycles of life and death when examining Mendieta’s work. Since she was uprooted from her home in Cuba as a child, many art historians interpret her Silueta series as seeking to re-root the body in place.

In The Tree of Life, pictured below, Mendieta covered herself completely with mud, fully incorporating her body into the landscape, her form making a raised impression against a tree. Making her body part of the earth, and allowing the There is a sense of intimacy in the scale of Mendieta’s performances; highlighted by the relationship between the artist’s body, the land, and the viewer.

Mendieta went on to create more than one hundred Silueta in Mexico, Iowa, and Cuba (where she returned to visit in 1981) covering her body with a wide range of substances, including rocks, blood, sticks, sand, and cloth. Or, she’d make an impression right in the earth, letting it fill up with water or sometimes red pigment. There is a relationship between Mendieta’s series and Santería, which is an African diasporas religion a commonly practiced in Cuba. Santería’s use of natural symbols, such as earth, blood, water, and fire, are echoed in Mendieta’s practice.

Through her performances, Mendieta is considered important to feminist art history. Like other women discussed in this chapter, Mendieta controls the presentation of her own body, taking an active role in how the viewer sees her (or doesn’t). She also takes a non-invasive approach to the land, rather than altering it, she becomes a part of it by gently and temporarily transforming it through her presence. Finally, Mendieta’s work mediates feelings of displacement and indeterminacy; this sense of ephemerality and vulnerability arguably helps her work transcend her individual identity and biography by questioning the physical experience of being a part of the world.

In Her Own Words: Ana Mendieta’s Artist Statement

Artists write statements to describe their work and their interests. Read Mendieta’s statements below to better understand her aims. (Excerpts are from Olga Viso, Unseen Mendieta: The Unpublished Works of Ana Mendieta, Munich, Berlin, London and New York 2008.)

“The first part of my life was spent in Cuba, where a mixture of Spanish and African culture makes up the heritage of the people. The Roman Catholic Church and “Santeria”—a cult of the African divinities represented with the Catholic saints and magical powers—are the prevalent religions of the nation. For the past five years, I have been working out in nature, exploring the relationship between myself, the earth, and art. Using my body as a reference in the creation of the works, I am able to transcend myself in a voluntary submersion and total identification with nature. Through my art, I want to express the immediacy of life and the eternity of nature.” (Ana Mendieta, 1978)

“I have been carrying out a dialogue between the landscape and the female body (based on my own silhouette). I believe this has been a direct result of my having been torn from my homeland (Cuba) during my adolescence. I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature). My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that unite me to the universe. It is a return to the maternal source. Through my earth/body sculptures I become one with the earth … I become an extension of nature and nature becomes an extension of my body. This obsessive act of reasserting my ties with the earth is really the reactivation of primeval beliefs … [in] an omnipresent female force, the after-image of being encompassed within the womb.” (Ana Mendieta, 1981)

“For the last twelve years, I have been carrying on a dialogue between the landscape and the female body. Having been torn from my homeland (Cuba) during my adolescence, I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast out from the womb (Nature). My art is the way I reestablish the bonds that unite me to the Universe. It is a return to the maternal source. These obsessive acts of reasserting my ties with the earth are really a manifestation of my thirst for being. In essence, my works are the reactivation of primeval beliefs at work within the human psyche.” (Ana Mendieta, 1983)

Stop & Reflect: Ana Mendieta

- How do you think Mendieta’s exile from Cuba influenced her artwork? How are feelings of displacement and dislocation explored in her works?

- What aspects of home resonate with you on a sensory level?

- What materials does Mendieta use to create her work?

- Can you describe the role of the body in her artwork?

- How are life and nature intertwined in Mendieta’s work?

- How do the works in the Silueta series suggest the fragility of the human being in relation to the forces of nature?

Hannah Wilke, Gestures, 1974

Hannah Wilke (1940-1993) was an American artist whose intermedia works combined performance, film, sculpture, painting, and photography. Gestures is a recorded, durational performance that shows the artist manipulating her face with her hands for the length of the video (about 35 minutes). She pushes, pinches, smooshes, and pulls at her face, stretching and contorting it like clay, a material she often worked with before creating her first video work. These gestures ask the viewer to question standards of conventional beauty. Referring to these explorations as performalist self-portraits, Wilke used her body to play with ideas of abstraction and representation, and to call attention to how women’s bodies are objectified.

Using her hands, her face transforms, interrupting the viewer’s gaze, and calling attention to the commodification of the female body. Wilke, like Yoko Ono, Carolee Schneemann, and Ana Mendieta, uses her own body in an effort to reclaim it and define it herself, within a patriarchal society. She says, “I made myself into a work of art. That gave me back my control as well as dignity.” (Wilke, quoted in Montano, p. 139).(You can read more about Gestures in the Early Video Art chapter.)

Stop & Reflect: Hannah Wilke

Hannah Wilke, Gestures, 1974, video (black and white, sound), 35:30 minutes. (Excerpt included below is just 0:58.)

Questions to Consider:

- Wilke’s work addresses female objectification through the exploration and transformation of her own face and body. Why do you think self-representation is important to Wilke?

- How does Gestures compare to Schneemann and Mendieta’s use of their bodies in examples examined earlier in this chapter?

Focus: 1980s: Ritual Space

The artists presented in this section create space for performance outside the traditional museum or gallery setting. Allan Kaprow and Tehching Hsieh explore patience and time through their durational performances, while David Hammons reclaims space for Black bodies through his ephemeral performances.

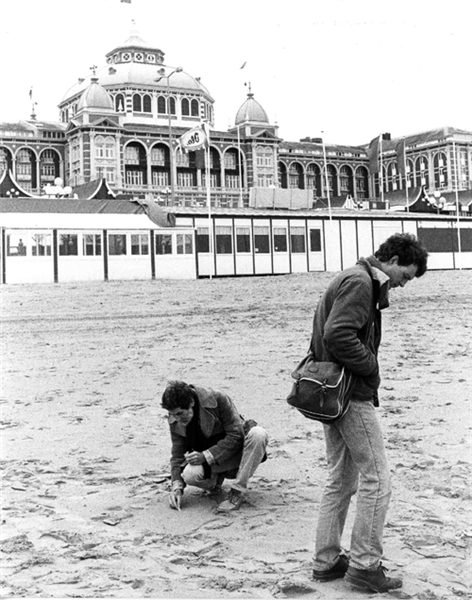

Allan Kaprow, Trading Dirt, 1982/83-1985

An early practitioner of participatory art, Allan Kaprow (1927-2006) valued the performative possibilities of all forms of art. Known for developing the Happening in the late 1950s, Kaprow’s later work included meditative performances, such as Trading Dirt. This durational performance, dematerialized the art object, while at the same time, it ritualized the mundane process of moving dirt from one person and place to another. Trading Dirt began in 1982 or 1983 when the artist was studying at the Zen Center in San Diego, California and represents a shift from his earlier Happenings of the 1960s, to a more intimate and time-based work.

Trading Dirt is referred to as a durational performance because the passage of time is an essential element to the work. The work unfolds sporadically over a number of years, whenever Kaprow felt like initiating the process, ending in about 1985. Kaprow begins the performance by trading buckets filled with dirt from the Zen Center for dirt from his own backyard. He then trades soil with friends, farmers, and others. The act of trading dirt, especially with strangers, led to spontaneous actions and conversations that become a part of the work. You can watch Kaprow tell a story about the process and his motivations for Trading Dirt in a video from Media Art Services linked here (14:36 minutes).

Influenced by composer John Cage’s emphasis on the sounds between the notes (See his 4’33” for example. You can also find a further discussion of Cage’s influence in the chapter on Social Practices.), Kaprow was interested in the human interactions and chance encounters between the act of trading dirt.

Of Trading Dirt, Kaprow writes, “The dirt trading and the stories went on for three years. It had no real beginning or end. The stories began to add up to a very long story, and with each retelling they changed. When I stopped being interested in the process (it coincided with my wife and I having to move after our rental property was sold), I put the last bucket of dirt back into the garden.” (Trading Dirt, 1982/83-1985) (Kaprow, 1993)

Stop & Reflect: Allan Kaprow

- Kaprow wrote, “‘Life is much more interesting than art. The line between art and life should be kept as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible” (Kaprow, Untitled, p. 709). How does work, like Trading Dirt, exemplify this quote?

- How does Kaprow’s work honor chance encounters and lend significance to everyday events?

- Can you relate Happenings back to what you’ve learned about Dada and Fluxus?

- As we’ve noted, many of the artists discussed in this text make work that is difficult to categorize and can be understood through multiple lenses. Read about Allan Kaprow’s Happenings in the Social Practice chapter, if you have not already done so. What are some differences between the way his work is contextualized in that chapter vs. the way his work is contextualized in the history of performance art?

- Why do you think Happenings fit into both categories?

Tehching Hsieh, Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980-1981), 1980-81

Another example of a durational performance is Tiwanese American artist, Tehching Hsieh’s (born 1950) Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980-1981). Durational performances can express an artist’s endurance because they happen over a long period of time. Hsieh’s performance everyday, for a full year, also explores our relationship to time by revealing it as a precondition for all life.

Scholar Ash Dilkes discusses Hsieh’s interest in collapsing boundaries between “art time” and “life time.” In a durational performance, lines between art and life are ultimately blurred as Hsieh must wake himself up every hour to punch a time clock, which he has installed inside his studio, for the duration of the yearlong performance. The process of documentation became so a part of Hsieh’s daily routine that he only missed 133 punches out of 8,760 (Dilkes). His life is the performance; art and life are experienced simultaneously, reflecting a culmination of a central goal of Performance Art as the boundaries between art and life are dissolved.

Stop & Reflect: Tehching Hsieh

Watch the following 2 videos on Tehching Hsieh and his performance practices (2:36 and 3:38 minutes):

Next, watch the artist and curator Nina Miall discuss Tehching Hsieh’s Time Clock Piece (the second of his one-year performances). (Das Platforms Multimedia Projects, 9:05 minutes):

Questions to Consider:

- Watch the stop motion embedded above. How is the passage of time reflected in Hsieh’s self-portraits?

- Consider the role of process in Hsieh’s performance. Do you think the artist’s experience of creating the work is more important than any objects or records that are the outcome of the process? Why or why not?

- What do the installation views of the performance reveal to the viewer about Hsieh’s performance and process?

- Especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, can you describe a moment from your own life that helps you relate to the repetitive quality of Hsieh’s work?

David Hammons, Bliz-aard Ball Sale, 1983

David Hammons (born 1943) is a sculptor, printmaker, performance, and installation artist known for his ephemeral public performances and installations. Remaining intentionally elusive to the museum and gallery systems, Hammons’ work explores and critiques systemic racism in the United States. In David Hammons: Bliz-aard Ball Sale, author Elena Filipovic writes:

“You cannot think of these works or of Hammons’ street actions in general without reckoning with what blackness meant (and means still) in public space. Or without acknowledging that by putting himself out on a street corner with his wares, Hammons may well have been playing with racist stereotypes associated with blacks (homeless vagrant, street hustler, drug pusher) and at the same time undercutting them through his calm, serious stance and willfully elegant style. The adage “the white man’s ice is colder” speaks for the sort of internalized racism that causes black Americans to believe that businesses, products and services offered by whites are better, more reliable. Turning the expression on its head, Hammons’ act implicitly suggested that although you could easily make your own snowball, this black man’s ice was worthy of purchase; it was perhaps colder, even.”

Documented through photographs, Hammons performed Bliz-aard Ball Sale on a New York City street near Cooper Square in 1983. He laid out a woven rug and set out his snowballs, carefully arranging them in descending order, according to size. Each snowball was crafted using spherical molds, so they have a perfectly round shape, something you couldn’t as easily achieve if you formed each snowball by hand.

In addition to evaluating Hammons’ street actions as a reflection on his experience as a Black American, another way to interpret Bliz-aard Ball Sale is as a critique of the art market and the value attributed to artworks by galleries and auction houses. The snowballs Hammons hawked were, by their very nature, ephemeral objects that he seemingly sought to profit from. They are also commonplace (especially in New York in December), so by assigning value to them, Hammons draws attention to the arbitrary nature of the art market, presenting a contrast between the art world and the more tenuous financial position of the street vendor.

Stop & Reflect: David Hammons

- In an interview, when asked whether or not he thought is work is political, Hammons replied, “I don’t know. I don’t know what my work is. I have to wait and hear that from someone.” So, what do you think? What is an argument for Hammons’ work as political? If not, what do you think his work is about?

- In what ways would being presented in a museum or gallery space change the meaning of Blizz-ard Ball Sale? Why is site important to Hammons’ performance?

Focus: 1990s: The Social Body

In this next section, we’ll turn to three artists whose performances address politics and identity. For our case studies, we’ll review a performance by the Chinese artist Zhang Huan whose work about the human condition pushes his own body to extremes, often under the watchful and suspicious eye of the Chinese authorities. We’ll also study work by Tania Bruguera, a Cuban artist who conceptualizes performances critical of the Cuban government and of authoritarianism more broadly. She has had her passport confiscated and her works banned in her home country. Finally, we’ll look at Mona Hatoum, a Palestinian performance, multimedia, and installation artist whose piece, Roadworks (Performance Stills), investigates how individuals struggle under authoritarian control.

Zhang Huan, 12 Square Meters, 1994

Zhang Huan (born 1965) is a Chinese artist who lives and works in both Shanghai and New York. In 12 Square Meters we see, through photographic documentation, the artist seated, naked, on a toilet in a public restroom. The title refers to the size of the room, which is 12 meters, or about 130 square feet. His body appears to shine, a result of being smeared with fish oil and honey, and we can see that flies and other insects have landed on him.

As the artist sits in this small, enclosed lavatory, during the summer, covered in oil, honey, and bugs, how would you describe his expression? What other senses does this work engage? Can you imagine the smell of the public restroom? Can you feel the air and sense the temperature of the space? Is it warm? Humid?

Zhang Huan sat in this restroom for hours at a time. The restroom is in an economically disadvantaged town outside of Beijing called Dashancun Village. Zhang and other artists called this area, where they also had art studios, Beijing East Village, after the New York neighborhood, Greenwich Village, known for its many artists. This was a subversive dig at contemporary Chinese artists who were living and working in more affluent areas of Beijing. The work Zhang and his contemporaries were creating in Dashancun called attention to the area’s squalid living conditions, and remained both physically and conceptually outside the Chinese government’s institutionally sanctioned art.

Let’s consider the role meditation and endurance play in Zhang’s performance. He sat, perfectly still, seemingly unbothered by his surroundings. In his essay, “Revising Performance Art of the 1990s and the Politics of Meditation,” Hentyle Yapp, Assistant Professor of Art and Public Policy at New York University, writes,

“Meditation structures Zhang’s performance in 12 Square Meters. He does not merely endure through discomfort; he allows it to become a form of practice and self-cultivation. Zhang’s sitting, along with his acute sense of focus, is located within his present moment, not within the past or future.”

Think about this quote in the context of Zhang’s performance. What do you think it implies? Did Zhang accept his surroundings? How does enduring something become an avenue for self-actualization?

Stop & Reflect: Zhang Huan

- If you could create a durational performance piece critical of an aspect of where you live, what would it be?

- Can you think of nine adjectives to describe Zhang’s performance? How are these adjectives supported by your understanding of his work?

Tania Bruguera, El Peso de la Culpa (The Burden of Guilt), 1997-1999

Tania Bruguera (born 1958) is a Cuban visual, performance, and social practice artist. Her work is often political in nature criticizing, for example, the lack of free speech under Fidel Casto’s rule in Cuba.

In El Peso de la Culpa (The Burden of Guilt) Bruguera revisits Cuban history. Her work responds to a story of indigenous people who vowed to eat nothing but dirt, rather than become prisoners of the Spanish conquistadors. In the performance, Bruguera stands in front of a Cuban flag that’s made of human hair, and wears a butchered lamb around her neck. She takes her time mixing dirt (earth) and salt (tears), which she then eats. This performance acknowledges indigenous Cubans who took their own lives by starving themselves as an affront to the abuse of the colonizing Spanish.

Bruguera uses non-traditional art-making materials in her work: dirt, salt, her own body, hair, and animal flesh to make connections between life for Cubans during colonization and after the collapse of the Soviet Union. By eating dirt, Bruguera connects these two moments in Cuban history, reflecting on both the strength and poverty of the Cuban people. This connection also reinforces Burguera’s notion of the social body, meaning that she sees her body not only as her own, but as representing Cuban people and Cuban history, collectively. Her body takes on the burden of this history, collapsing time and space and revealing the lack of freedom afforded to the Cuban people, across centuries.

Finally, Bruguera prefers the term Behavior Art to describe her work, which she describes as moving beyond performance and more readily connecting art to a sociopolitical agenda. She writes in “Arte de Conducta” on her website that Behavior Art retains the utilitarian potential of art. Rather than art rendered “ineffective” by its placement in an institution, like a museum with its focus on formal qualities, art can live outside the walls and on the streets with people.

Stop & Reflect: Tania Bruguera

- How does the term Behavior Art compare to Fluxus? Do you think it offers a continuation, or modernization, of Fluxus ideals?

- What are sociopolitical realities expressed in Bruguera’s work?

- Can you point to specific ways history manifests in Bruguera’s performance? Why do you think it is important for the artist to reflect on this history?

- Keep her concepts of Behavior Art and the social body in mind when we examine two more of her artworks in the section Performance Art Now, below. Then, compare and contrast her performance strategies.

Mona Hatoum, Roadworks (Performance Stills), 1985-1995

Mona Hatoum (born 1952) is a Palestinian performance and multimedia installation artist who lives in London. She was born in Beirut, Lebanon to Palestinian parents, and traveled to London for a visit in 1975; she became stranded there due to war breaking out in Lebanon. Like Ana Mendieta, discussed earlier in this chapter, Hatoum’s work often addresses feelings of displacement and explores her identity as a person living in exile.

In 1985, she created three pieces for an exhibition called Roadworks, which she performed around the district of Brixton, in southern London. The exhibition, organized by the Brixton Art Gallery, sought to move art from beyond the gallery walls through a series of unannounced performances that took place around the city, in order to reach new audiences. The image pictured above is a record of one of those performances. In it, we see the artist’s legs, photographed in mid-stride from about the knees down, as she walked barefoot through the city streets for about an hour. Tied around her ankles by their laces is a pair of black Doc Marten combat boots. Photographic evidence of this series of performances was published a decade after they took place.

In the early 1980s, intense protests for racial justice occurred in Brixton due to its racist policing and housing policies, which disproportionately targeted Black Londoners (Brixton has a large African and Caribbean population). In 1985, the same year as the Roadworks exhibition, a Black woman was shot by the police in Brixton during a raid on her home, leaving her paralyzed from the waist down. More protests followed. In this context, Hatoum’s performance can be interpreted as a response to the city’s trauma. Are the black boots following her, or holding her down, or is she marching in solidarity with the community?

Hatoum shared stories of this work in a 1991 interview saying, “‘One comment I really liked was when a group of builders, standing having their lunch break, said ‘What the hell is happening here? What is she up to? And this black woman, passing by with her shopping, said to them, ‘Well it’s obvious. She’s being followed by the police.'” (Diamond, 131). Hatoum’s performance, taking place unannounced and outside of the traditional art space, allowed viewer’s to form their own interpretations of the work, connecting it to their community’s current events. Like Tania Bruguera and Zhang Huan, Hatoum’s body becomes the social body, the big black boots following her symbols of both individual and societal oppression.

Stop & Reflect: Mona Hatoum

- Hatoum stipulates that the photograph of her performance, which is printed on reflective aluminum, be exhibited directly on the floor, leaning against the museum or gallery walls. How does this means of display reflect the intermedia qualities of New Media? Do you think placing the photograph on the floor creates more or less of an interactive space for the viewer to experience the work?

Focus: Performance Art Now

This final section showcases examples of performance art from the last two decades. As you’re reviewing the case studies presented below, think back to the previous examples we’ve examined in this chapter and see if you can make connections between earlier and later performance art.

You’ll learn more about Theaster Gates in the Social Practice chapter of this text, so keep in mind how artists who work in contemporary performance art continue to work across media and genres. We’ll also take another look at Tania Bruguera’s work in this section and it is useful to compare and contrast the examples presented below and El Peso de la Culpa (The Burden of Guilt), discussed above. Finally, consider how Dread Scott’s work, which is the first case study you’ll encounter in in this section, connects to the sociopolitical performances examined throughout this chapter.

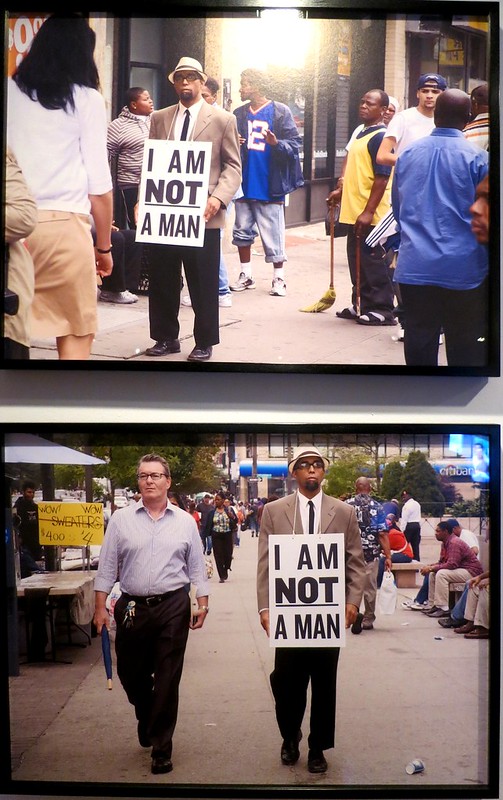

Dread Scott, I Am Not a Man, 2009

Dread Scott (born 1965) is an American artist whose practice in performance, installation, video, printmaking, and painting critically examines race and racism in the United States. Of his multimedia approach, Scott writes in his artist statement on his website, “two threads that connect them are: an engagement with significant social questions and a desire to push formal and conceptual boundaries as part of contributing to artistic development.” What connective threads can you identify in Scott’s statement? How do these threads fit in with the goals of performance more broadly? As you learn more about his performance, I Am Not a Man, keep Scott’s intentions as an artist in mind.

In I Am Not a Man, Scott walked the streets of Harlem, New York for an hour. He’s dressed in a tan suit jacket with black pants, a black tie, and a white shirt. He wears black-rimmed glasses and a tan and brown hat. He’s also wearing a large signboard with the words, “I AM NOT A MAN.” The sign references the 1968 Memphis Sanitation workers strike and the artist Glenn Ligon’s 1988 painting (Untitled) I Am Man (which also refers back to the sanitation strike).

As you can see from the still images of the performance, Scott’s work attracts attention from people on the street. At one point, he’s surrounded by a group of police officers (you can hear Scott talk about this encounter on The Modern Art Notes podcast). In the last image on his website, he is shown with his pants down. Here, Scott’s performance recalls a specific moment when he witnessed police officers searching a Black man on the street by pulling his pants down. In other parts of the performance, Scott puts his hands up against the wall, lays down on the ground, and pulls the pockets of his pants inside out.

Stop & Reflect: Dread Scott

- Listen to an interview with Dread Scott that aired on June 3, 2020 on The Modern Art Notes podcast (50:09 minutes; I Am Not a Man is discussed at 26:47 to 32:52)

- Look at still images from I Am Not a Man from Scott’s website. Be sure to also scroll down below the images to read his statement about the work.

- As you look through images of I Am Not a Man and listen to the artist speak about his work, think of specific ways Scott’s work critiques the way Black Americans are treated in the United States.

- What is the effect of the use of text in Scott’s performance? Would this piece be different if the artist had walked the streets of New York declaring, “I am not a man,” aloud? Why or why not? Would the effect of this performance be different if it were performed in a museum or gallery space?

- How does Scott’s work reflect directly on history? You can read more about the Dred Scott Supreme Court decision on the PBS website and more about the Memphis Sanitation Strike of 1968 on the Civil Right Museum website.

Tania Bruguera, Tatlin’s Whisper #5, 2008 and Tatlin’s Whisper #6, 2009, collaborative performances

As discussed in the pervious section, Politics and Identity, Tania Bruguera is an artist whose work defies easy categorization. Her work is often explicitly political and based on viewer participation and interaction, and participation from the institution, such as the museum. In addition to using the terms Behavior Art and the social body to describe her practice, she also refers to what she does as initiating (rather than creating) a work of art, preferring to work collaboratively with others to decentralize the role of the artist. Her work fits in with both performance and social practice.

Watch Tatlin’s Whisper #5 performed at the Tate Modern museum, above. (Tate Shots, 4:00 minutes) and read about Tatlin’s Whisper #5 on the artist’s website.

Tatlin’s Whisper #5 shows two mounted police officers directing the crowd inside the great Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern museum in London, England. The people encounter the mounted police as they perform their typical job, but they’ve been taken out of their usual context and placed inside the museum space; Bruguera describes this as the “decontextualization of an action.” People don’t have to obey them, but they do. The authority of the mounted police extends to this new context. In the video from the Tate Modern, Bruguera says that she prefers when the audience can experience the work as a live event, rather than a representation of a live event.

Tatlin’s Whisper #6 (Havana Version) also addresses power and authority. In this case, Bruguera presents the viewer with the symbols of a political speech: a microphone and podium, flanked by two guards (who are actors), in front of a curtained backdrop. Audience members are invited up to the microphone and allowed 1 minute to say whatever they want; they have one minute of totally free speech before they are pulled from the podium by the guards. As you can see in the Art21 video clip linked to above, people scream, cry, and yell into the microphone.

Stop & Reflect: Tania Bruguera

- Read about Tatlin’s Whisper #6 (Havana Version) on the artist’s website

- Watch an excerpt from the performance from the Art21 interview with Bruguera (the discussion of the artwork starts at 23:35).

- How does Bruguera’s work expand the definition of performance art?

- How do the works presented in this section compare to El Peso de la Culpa (The Burden of Guilt) discussed earlier?

- What role does absence place in Tatlin’s Whisper #6 (Havana Version)?

- What political message do her works convey? How does she communicate these messages?

- How does Bruguera’s approach to performance differ from the other artists examined so far in this chapter? Does she use a different approach to engage the audience?

- Do you think the outcome of the performance changes when the artist’s body is not present?

Theaster Gates, See, Sit, Sup, Sip, Sing: Holding Court, 2012 and Processions, 2016-2019, series of collaborative performances

You learned about the American artist Theaster Gates (born 1973) in the Social Practices chapter. Below, you’ll study two of his collaborative performances, which are an extension of his social practice work.

Watch a few minutes of Gates’ performance of See, Sit, Sup, Sing: Holding Court from the Studio Museum in Harlem (22:50 minutes)

In See, Sit, Sup, Sip, Sing: Holding Court, Gates initiates another type of space for conversation. This collaborative project is part performance and part installation. It also plays with ideas of presence and absence, similar to Bruguera’s Tatlin’s Whisper #6 (Havana Version).

See, Sit, Sup, Sip, Sing: Holding Court consists of salvaged materials (like The Dorchester Projects) from a closed public school in Chicago’s South Side. The chairs, desks, tables, and chalkboards are arranged to encourage learning and listening.

When the space is activated, people fill the chairs, the chalkboard is covered in questions and ideas, and voices rise and fall in conversation and community. Gates occasionally “holds court,” but the space can be used freely by others. When the space is empty, it sits as a silent reminder of the importance of learning from one another, and the institution’s role in listening to its community.

Read about Processions on the Hirshhorn Museum website, where you can also view still images of the different performances and watch a video of The Runners (4:48 minutes.), embedded above.

His project, Processions at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. was a series of four collaborative performances that the artist created with local and national Black community arts leaders.

A true intermedia project, Processions combined dance, music, theater, visual art, and African American culture. Several of the performances were part improvisational as Gates collaborated with choral singers, experimental music ensembles, and even student athletes.

Stop & Reflect: Theaster Gates

- Community collaboration and creating opportunities for exchange and dialogue are at the heart of Gates’ practice. Can you compare Gates’ process for Processions with his work on The Dorchester Projects, reviewed in the Social Practice chapter?

- How do these works each reflect Gates’ focus on fostering community? How do they also relate to supporting and celebrating Black identity?

Conclusion

This chapter introduced you to a broad range of artistic practices encompassing performance art. As we’ve seen, performance art challenges the hierarchy of the institution by pushing out of the museum or gallery walls, and bringing art out into the public sphere. Performance also de-centers the importance of the art object, valuing instead the ephemeral actions of the artist. This shift to action over object reveals performance artists’ interest in demonstrating that art exists in real life and in real time, rather than as a commodity available to only a privileged few.

As we saw in other chapters discussing Institutional Critique and Social Practice, New Media artists seek out new modes of expression that are less and less tied to historic, Western notions of how we view and experience works of art. Performance artists also recognize this shift and seek to create work that engages the viewer and encourages their active participation in the creative process.

Key Takeaways

At the end of this chapter you will begin to:

- Explain the context and history of Performance Art.

- Describe and compare significant pieces of Performance Art.

- Recognize developments in Performance Art and consider how this approach to art is connected to the broader history of visual culture.

- Explain how Performance Art relates to the elements of New Media Art.

Optional: Lesson Extensions

Below are some lesson extension activities to encourage learners to engage more deeply with the material presented in this chapter.

Further Reflection:

- How would you define performance art? How does performance push back against conventional ways of viewing and experiencing an artwork?

- How does performance art differ from the theater?

- Can an original piece of performance art be performed again? Should it be?

- Is performance art designed to make you uncomfortable?

- What are some of the historical precedents for performance?

- How does performance art draw attention to the intersection of art and life?

- How does performance anticipate other forms of new media?

- Why do you think the body becomes so central to Performance Art?

Creative Interpretation Idea

Create a Fluxus Event Score

We’ve learned that Fluxus artists desired to merge art and life and often called attention to the ordinariness or mundane aspects of our day-to-day experiences. Their work relies on audience participation and chance.

For this assignment, you will compose an original Fluxus event score inspired by your immediate surroundings.

Your work will be evaluated according to the following criteria:

- Your score is inspired by the Fluxus movement but is not derivative of another artist’s work.

- Your score is about 4-6 lines long (it can be a bit shorter than this, but should not be much longer).

- Your score is based on a specific site or feeling inspired by your immediate surroundings.

- Feel free to be creative with your presentation. You can play with fonts, layout, color, and graphics to create a score that reflects your inspiration.

Discussion Assignment Idea

As you learned in this week’s module on performance art, artists can break down the barriers between art and life by:

- performing and presenting work outside the traditional venues (e.g., museums or galleries)

- engaging the audience in the public sphere

- using everyday (non-art) materials

Select one of the artists presented as case studies in this chapter and discuss how their work breaks down barriers between art and life. You can base your response on the criteria above, but you may also share other ideas about how artists can blur the lines between art and life inspired by the artist and artwork you’ve chosen.

Further Reading

Read the interview, “Tehching Hsieh and Marina Abramović in Conversation” from the Tate Museum’s website.

Based on your understanding of the reading, respond to the following questions:

- How are Tehching Hsieh’s and Marina Abramović’s artistic practices the same? How do they differ?

- Can you explain, from the reading, how each artist prepares for a performance?

- Pick a quote from the reading by either artist. Why did this quote resonate with you? What do you think it reveals about Hsieh’s or Abramović’s artistic philosophy?

Selected Bibliography

Cummings, Andrew. “Art Time, Life Time: Tehching Hsieh.” Tate Research Centre: Asia Event Report, July 2018. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/research-centres/tate-research-centre-asia/event-report-tehching-hsieh. Accessed September 12, 2020.

Diamond, Sara. “Performance: And interview with Mona Hatoum.” Fuse Magazine, 10 (5). pp. 46-52. http://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/1792/.

Frederickson, Kristen, and Sarah E. Webb. Singular Women: Writing the Artist. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt5b69q3pk/.

Goldberg, RoseLee, and Margaret Barlow. “Performance art.” Grove Art Online. 2003; https://www-oxfordartonline-com.libproxy.pcc.edu/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000066355. Accessed September 13, 2020.

Kaprow, Allan. “Just Doing.” TDR (1988-) 41, no. 3 (1997): 101-06. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1146610. Accessed September 10, 2020.

Kaprow, Allan. “The Education of the Un-Artist,” Part 2. In Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Katz, M. Barry. “The Women of Futurism.” Woman’s Art Journal. Vol. 7, No. 2 (Autumn, 1986 – Winter, 1987). 3-13.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extension of Man. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994.

Montano, Linda. “Hannah Wilke Interview,” in Performance Artists Talking in the Eighties. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Museum of Modern Art Learning. “Media and Performance Art.” New York: Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/media-and-performance-art/. Accessed August 1, 2020.

Museum of Modern Art Learning. “Yoko Ono, Cut Piece.” New York: Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/yoko-ono-cut-piece-1964/. Accessed August 1, 2020.

Perrot, Capucine. “Mona Hatoum, Performance Still 1985–95.” In Performance At Tate: Into the Space of Art. Tate Research Publication: London, 2016. Accessed September 17, 2020. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/performance-at-tate/perspectives/mona-hatoum.

Poggi, Christine. “’Folla/Follia’: Futurism and the Crowd.” Critical Inquiry. Vol. 28, No. 3 (Spring 2002). 709-748.

Rainey, Lawrence, et al., editors. Futurism: An Anthology. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1nq4q3.

Savin, Ada. “Tania Bruguera’s ‘Travelling Performances’: Challenging Private and Public Spaces /Voices.” e-cadernos CES. Online since June 15, 2017. http://journals.openedition.org/eces/2240. Accessed September 16, 2020.

Schneemann, Carolee. More Than Meat Joy: Complete Performance Works and Selected Writings. Ed. Bruce McPherson. New Paltz, N.Y.: Documentexte, 1979.

Taylor, Rebecca. “Marina Abramović, The Artist is Present,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed July 5, 2021, https://smarthistory.org/marina-abramovic-the-artist-is-present/.

Wilson, Martha. “Performance Art.” Art Journal 56, no. 4 (Winter 1997).

Yapp, Hentyle. “Revisiting Performance Art of the 1990s and the Politics of Meditation.” LEAP 21. August 8, 2013. http://www.leapleapleap.com/2013/08/revisiting-performance-art-of-the-1990s-and-the-politics-of-meditation/. Accessed September 13, 2020.

Youngblood, Gene. Expanded Cinema. New York: Fordham University Press. 1970.