10 Institutional Critique

Institutional Critique: Critiquing the Art Institution

Stop & Consider: What is a Museum?

Before you begin this chapter, reflect on these questions:

- Can you name the types of museums that you have visited? What types of museums have you not visited?

- Have you visited art museums? If so, which ones? If not, which ones would you like to visit?

- What are your expectations when you visit an art museum? What are your expectations when you visit other types of museums? Imagine your experience.

- What is the purpose of a museum? What is the purpose of an art museum?

- How do museums define culture and society?

- Why do we collect?

- How do museums hold power in society? What is the authority of a museum? What is the influence of economics on the power of a museum?

Mining the Museum by Fred Wilson

In 1992 in the roles of artist and curator, Fred Wilson (born 1954) visited the archives and object storage areas of the Maryland Historical Society. He spent a lot of time in the archives and ultimately chose historical objects that impacted him and installed them in his own way, amongst the exhibits already on view, adding new meaning to the history made official by the Maryland Historical Society.

In one display case titled “Metalwork, 1793-1880”, Fred Wilson arranged silver repoussé pitchers and cups around a pair of iron slave shackles. As you look at this image, ask

- What meaning do these individual objects have for you?

- How does the meaning change when they are displayed together like this?

- Do you expect these objects to be displayed together?

In creating this exhibition, Fred Wilson “mined” the museum archives to find objects that spoke to parts of US history often hidden or glossed over. He has also explained that he “mined” or made the museum his, by finding evidence of his ancestors, evidence of the history of slavery and evidence of the systemic racism embedded in the institution.

The approach that Fred Wilson took for his exhibition Mining the Museum changed the art world by challenging museum curators to be more conscious of unspoken or hidden power dynamics in the museum context and how they use objects to tell stories. Wilson’s project also cemented an approach to art that we call “institutional critique.”

Stop & Reflect: Fred Wilson

- How does Fred Wilson’s approach to curating make you rethink the meanings of museum displays?

- How does this make you rethink the meanings created in museums?

- How did his project confront racism in museums and in US society?

If you have access through your library to the JSTOR database, use the link below to look at other images from Fred Wilson’s 1992 exhibition and discuss how he creates meaning in the different ways that he displays cultural artifacts.

Wilson, Fred, and Howard Halle. “Mining the Museum.” Grand Street, no. 44 (1993): 151-72. Accessed August 31, 2021.

Reflections 25 years later

Read Wilson’s reflections on the exhibition 25 years later and look at other images from the 1992 exhibition in this article.

Kerr Houston. “How Mining the Museum Changed the Art World.” BmoreArt, May 3, 2017. Accessed August 31, 2021.

Institutional Critique defined

Institutional Critique is an artistic approach that critiques institutions, often art institutions like museums and galleries by pointing out their power in society, from economic power to power in shaping what is seen as valuable and how history is remembered.

The approach of Institutional Critique, coinciding with Conceptual Art, began in the late 1960s and early 1970s in a climate in which social activism was strong with the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement, and the Antiwar Movement. Artists continued this critique in the 1980s often tied to identity politics. It is only recently that we see artistic institutions, like museums, responding to the critique to lay bare the power structures and to promote positive institutional change.

Watch & Consider: Institutional Critique

Watch this series of video lectures by Nicola Price. They are linked here and embedded below.

- Introduction to Institutional Critique (7:56 minutes)

- Rise of Institutional Critique (15:04 minutes)

- Institutional critique’s second generation (18:58 minutes)

- Contemporary institutional critique (20:24 minutes)

As you watch the video, reflect on these questions:

- Define Institutional Critique by using an example of an artist’s work from the videos.

- How does Institutional Critique intersect with Conceptual Art? Give an example from an artist’s work.

- How does Institutional Critique get its lineage from Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)?

- Give an example of art work that critiques institutional power. Explain what it is about the work that challenges the viewer to recognize institutional power.

- How do artists expose racism in institutions?

- How did museums, especially museum curators, eventually embrace and get involved in institutional critique? What are the implications of this? Is the critique as effective?

Artists Critiquing Art Institutions

Below you will find examples of artists who take different approaches to institutional critique, within art institutions. However, because art institutions are entangled with diverse forms of institutional power, many of these projects contain layers of critique exposing how art institutions are and have been complicit in systems of oppression since their inception.

Focus: Daniel Buren at the Guggenheim Museum

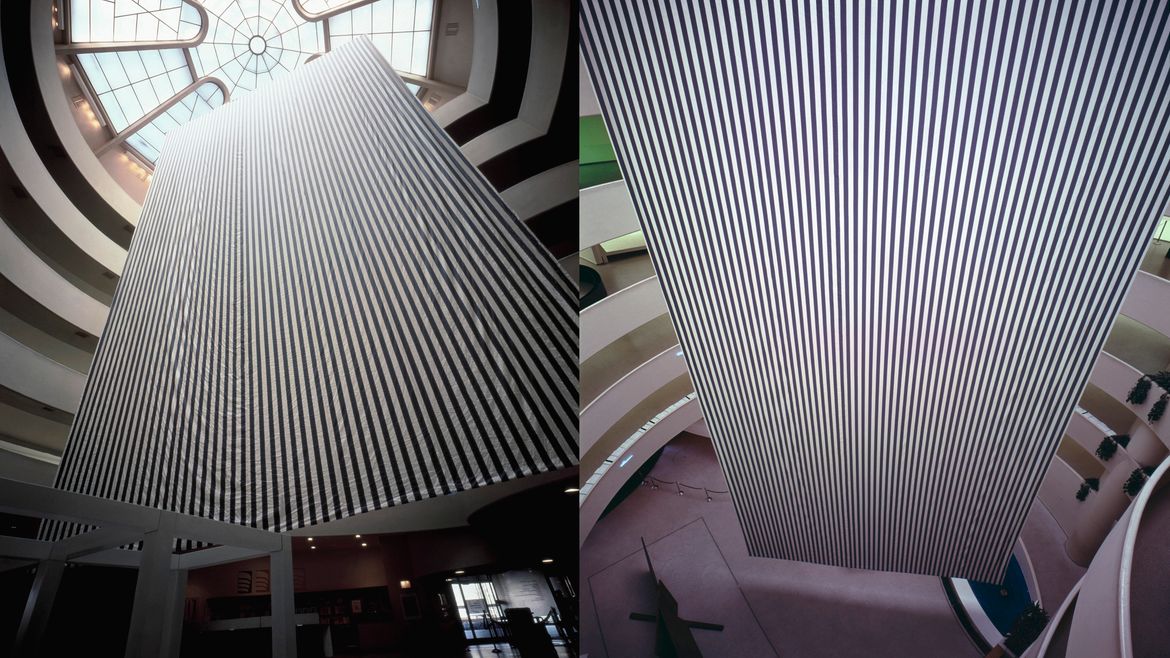

|

|

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum was built in New York City in the mid-twentieth century by the iconic Modernist architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959), and exhibitions in the Museum were central to the history of Modern Art after World War II. The structure is noted for its spiraling interior walkway that opens into multiple galleries as you walk up or down the ramp. As you exit the galleries onto the walkway, you are always brought back to the central atrium. The exterior facade of expresses the interior with its gleaming white concentric stacked circles growing in diameter to the top.

In 1971, French artist Daniel Buren (born 1938) hung a black and white striped painting almost 66 feet tall and 30 feet wide in the atrium at the center of the Guggenheim Museum and a smaller version outside across the street. The painting inside was removed before the exhibition opened.

Stop & Reflect: Daniel Buren

- What happens to the Museum when Daniel Buren installs this work?

- How do you think this piece impacted other works of art in the show?

- Buren said that the larger painting “placed in the center of the museum, irreversibly laid bare the building’s secret function of subordinating everything to its narcissistic architecture.” The Museum “unfolds an absolute power which irremediably subjugates anything that gets caught/shown in it.” What does he mean?

- Daniel Buren is considered a conceptual artist. How is this work Conceptual Art?

- Look at Daniel Buren’s Within and Beyond the Frame, 1973, installed October 13 – November 7, 1973 at the John Weber Gallery, New York City. The series of black and white striped paintings are hung on a line inside the gallery and out the window across the street. How does meaning change depending on the location of the paintings? How does this critique the institution of the art gallery?

Focus: Hans Haacke at the Guggenheim and MoMA

Hans Haacke (born 1936) has been known for his critical art. In his project Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971, he documented the large number of buildings in Lower Manhattan owned and controlled by members of one family who had ties to leadership of the Guggenheim Museum. The planned installation at the Guggenheim in 1971 was a series of framed documents including two maps of parts of New York City, one of the Lower East Side and one of Harlem. Haacke displayed rows of photos of building facades and empty lots, including data sheets and charts on business transactions related to the real estate.

The installation was withdrawn from the Guggenheim before it opened. The museum director refused to allow the work to be exhibited, saying that it was not art, it was not in keeping with the Guggenheim Museum’s charter of “pursuing aesthetic and educational motives that are self-sufficient and without ulterior motives.” (quote from New York Times article linked below)

Read, Listen & Reflect: Hans Haacke

View a detail of Hans Haacke’s Shapolsky et al. and listen to the curator’s comments at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Read more about the debate between the artist, museum director, and board of trustees:

Grace Glueck. “The Guggenheim Cancels Haacke’s Show,” New York Times, April 17, 1971. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- How does this work critique the institution of the art museum?

- How does it challenge the people who hold the power in the museum?

- Does this work have aesthetic qualities? Can you visually analyze this work? How important are those qualities in art?

- What does it mean to say that a museum is “self-sufficient and without ulterior motives”? How was Haacke trying to expose that statement as untrue?

- Hans Haacke is considered a conceptual artist. What makes this work Conceptual Art?

- This work is now collected by museums, like the Whitney, as you see in the detail linked above. Once the work becomes a part of the institution and its collections, does it lose its ability to critique? Is it as much of a critique now?

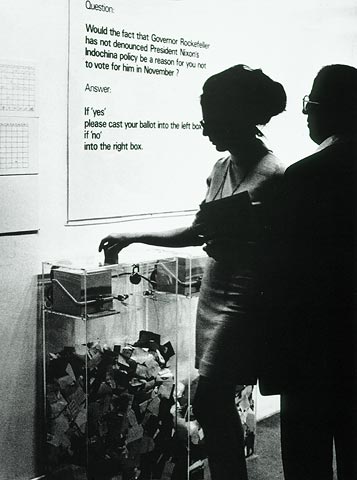

Look closely at the MoMA Poll below that Hans Haacke exhibited in another major art museum in New York City — the Museum of Modern Art. The poll reads: “Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller has not denounced President Nixon’s Indochina policy be a reason for you not to vote for him in November?” Nelson Rockefeller was not only Governor of New York at the time, but he was also a Trustee of MoMA. Additionally, there were allegations that Rockefeller companies were involved in manufacturing weapons for the American war in Vietnam.

- How does Haacke’s MoMA Poll critique the museum?

- How does it critique the viewer?

- In what ways does it engage the viewer beyond looking at art?

- If you were to create a poll like this, what question would you ask museum visitors? How would their answers show their biases? How would their answers reflect back on meaning that museums create?

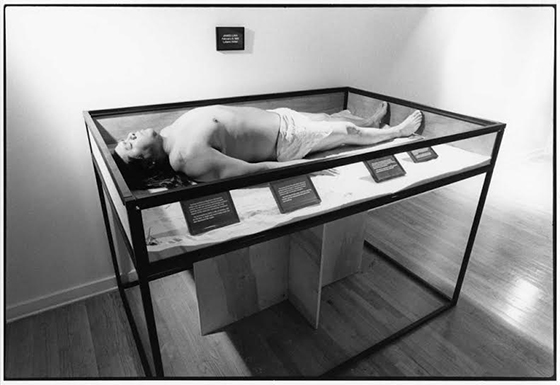

Focus: James Luna at the Museum of Man

As early as 1987, Luiseño (Payómkawichum) and Mexican-American artist James Luna (1950-2018) was using his art and art practice to critique colonial and racist ideas filtered through the institutions of museums. Luna used performance, photography, and installation of found objects to engage viewers in a conceptual critique of attitudes toward race and culture, in particular Native American culture. In The Artifact Piece, first performed in 1987 at the Museum of Man in San Diego, California, Luna laid in a display case wearing only a loincloth. Labels explained the origins of the scars on his body, and some of his personal possessions were included in the exhibition. Luna performed The Artifact Piece again in 1990 as part of the exhibition “The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s,” a collaboration of the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, the New Museum of Contemporary Art, and the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Stop & Reflect: James Luna

- Imagine visiting the museum and coming upon James Luna’s performance and installation as you were perusing the exhibits. How would you feel?

- How does his performance reveal objectification?

- How does Luna’s performance critique the institution of the museum and assumptions about cultures and histories?

- Why do you think this exhibition was continued as planned, while earlier works of Institutional Critique (like that of Daniel Buren and Hans Haacke, above) were removed and censored?

- What is Luna saying about the relationship between indigenous cultures and museums?

- Think about assumptions that people make about you, your race, culture, gender, or ability. What object or personal possession would you highlight to challenge those assumptions?

This piece is also considered an iconic example of Performance Art. Return to the chapter on Performance Art, and consider connections:

- How does this piece demonstrate some relationships between Performance Art and Institutional Critique?

- What Elements of New Media Art are expressed in Institutional Critique like James Luna’s The Artifact Piece?

Focus: Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña at the Quincentenary of Columbus’ arrival to the Americas

Cuban-American artist Coco Fusco (born 1960) and Mexican/Chicano artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña (born 1955) collaborated in performances that critiqued the relationship between colonialism and exhibition practices by referencing the display practices of World’s Fairs from the nineteenth century. Their series of performances titled Two undiscovered Amerindians visit the West marked the quincentenary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival to what is now called the Americas. They performed this piece at a variety of institutions, including the the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Columbus Plaza in Madrid and at other locations in the United States and in Europe. Along with critically examining the racist ideologies of historical exhibitions in ways that resonate with James Luna’s Artifact Piece, this series of performances also exposed the racist assumptions of contemporary museum visitors.

Watch & Reflect: Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña

Watch the trailer (1:53 minutes) for the video The Couple in the Cage (1993, by Coco Fusco and Paul Heridia, produced by Third World Newsreel) based on their performances and viewers’ reactions.

Questions to Consider:

- How do Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña use irony or tongue-in-cheek statements in their performances to make their critiques? What are some examples that you see here, and what are the critiques?

- In what ways are Fusco and Gómez critiquing museums with this project?

- Fusco has cited the treatment of historical figures like Sarah Baartman as informing this piece. After reviewing the Wikipedia entry presenting the history of Baartman’s life, what connections to you see?

- Watch interviews by both artists linked below. Listen to them talk about the techniques of their performances. Consider how their explanations add to your understanding of the concepts and ideas in their work:Listen to Coco Fusco, in an interview clip (2004), talking about her work with Guillermo Gomez-Peña (0:43 seconds). Fusco would interview people about what kind of ethnic show they would like, and Gomez-Peña would interpret their request in his own way.Now listen to Guillermo Gómez-Peña explaining his preparations for performance. (1:38 minutes runtime) in Works in Progress – Guillermo Gómez-Peña (from One Nation Films).https://vimeo.com/29757882Both Fusco and Gómez-Peña are also considered artists who do performance work. Return to the chapter on Performance Art, and consider the connections:

- How is the Institutional Critique of Fusco and Gómez-Peña related to the Performance Art you learned about in that chapter?

- What Elements of New Media Art are expressed in Institutional Critique like these performances by Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña?

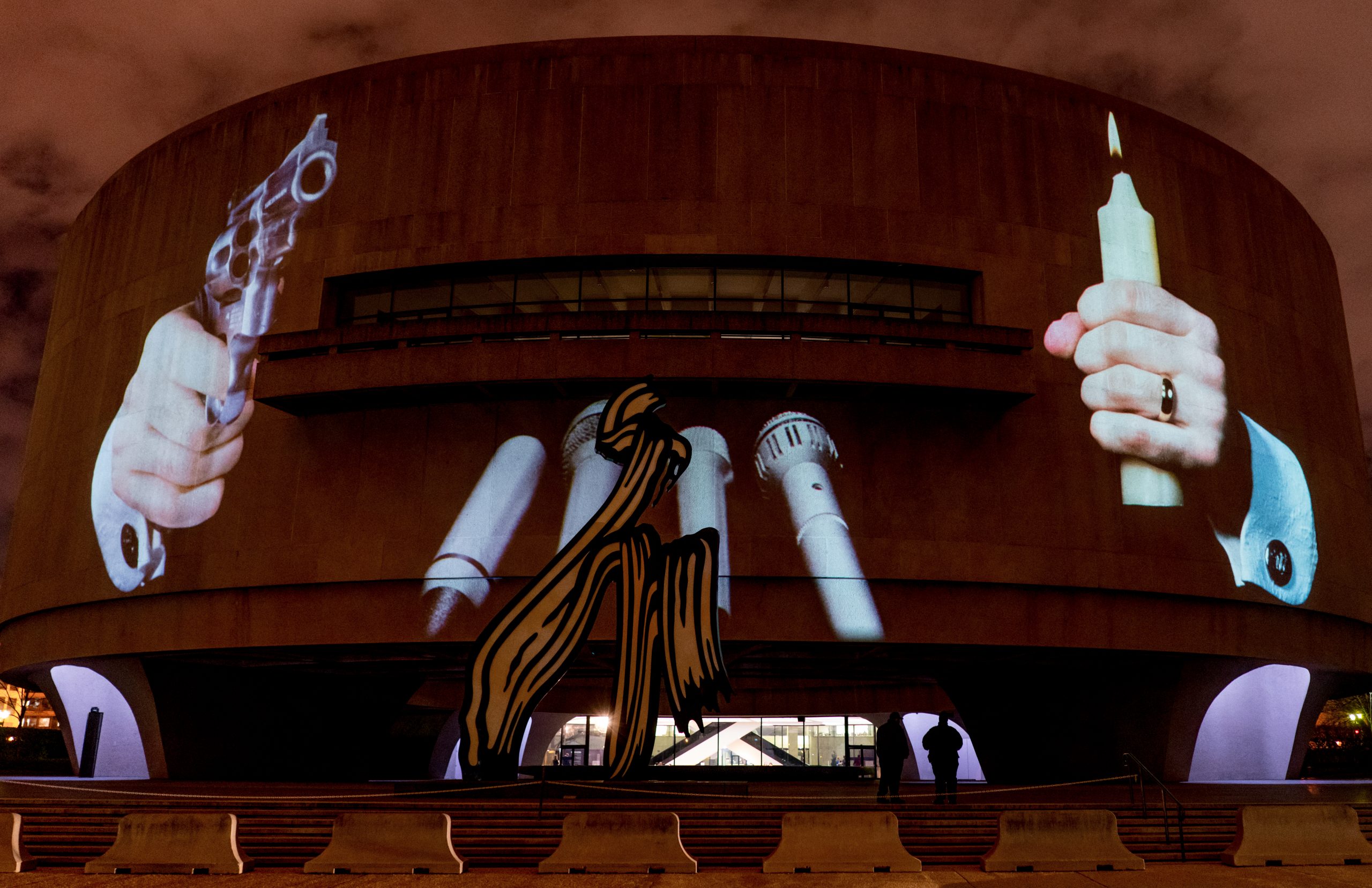

Polish-born New York artist Krzysztof Wodiczko (born 1943) projects symbolic images on public buildings, monuments, and other prominent sites to displace their customary public meanings. In the fall of 1988 for a few evenings during the Presidential election season, Wodiczko used xenon-arc projectors to project a 68-foot image of two hands onto the facade of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the contemporary art museum located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. and part of the Smithsonian Institution. One projected hand holds a revolver, and the other holds a burning candle. They both flank a row of four microphones. The cylindrical museum building under the projection suggests a face adding to the symbolism of the images. Visual elements like the light of the projected images draws your attention as you walk by, and the large scale of the images and of the museum building add to the power of the message.

In 2018, on the 30th anniversary of the original projection, the Hirshhorn planned to restage the project. The evening projections were postponed after the tragic shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. You can read about the restaging and find other supporting material on the Hirshhorn Museum website.

Watch & Reflect: Krzysztof Wodiczko

- In addition to the visual elements of light and scale discussed above, what elements of New Media Art can you tie to Wodiczko’s work?

- What meanings can you find tied to the symbols, visual elements, and elements of New Media Art? What is Wodiczko saying with this piece?

- Why is Krzysztof Wodiczko’s work a good example of Institutional Critique in art?

- How does the meaning change based upon the timing of the projections? in 1988? in 2018?

- For additional exploration, watch the Art21 segment “Krzysztof Wodiczko in ‘Power’” (13:33 minutes). How does Wodiczko’s projection project in St. Louis, Missouri relate to Social Practice in art (explored in the next chapter)?

- If you were to project an image on a building or monument, what building or monument would you choose, and what image would you project? How would your projections change or enhance the meaning of the building/monument and image?

Focus: Nancy Spero in the Museum

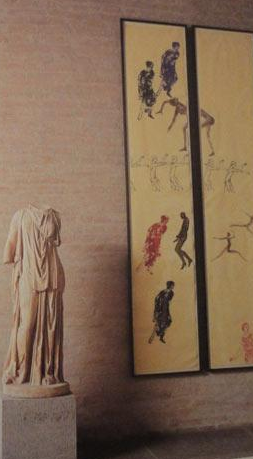

Unlike the artists discussed above, Nancy Spero (1926-2009) is not considered a New Media artist in terms of her artistic materials. She is also not noted as an artist who practiced Institutional Critique. However, as early as the 1980s, painter and feminist Nancy Spero began exhibiting her work in unconventional ways in museums and galleries. Beginning in the 1970s, Nancy Spero amassed a collection of mostly images of women, from prehistory to ancient to modern and contemporary times, and she reworked these images into her own lexicon that critiques violence against women in some combinations and in others, the images depict a bodily freedom for women. Spero repositioned and reconstructed these images from history in expressive drawings and prints on paper to amplify these feminist messages. By the late 1980s, she was challenging the institutions of art museums, art galleries, and the art market by displaying her images in the museums or galleries in unconventional ways. Spero printed her images directly on the walls in unexpected places. She hung her drawings and prints above or below eye level in galleries. In 1991, in an exhibition at the Glyptothek in Munich, Germany, Spero incorporated her drawings and prints among the ancient Greek and Roman sculptures bringing new meaning to the works, to the materials of art, challenging the Western male-dominated histories and architectural styles.

Stop & Reflect: Nancy Spero

Look carefully at the images of Nancy Spero’s works displayed in the art museums above.

- How are these works displayed in unconventional ways?

- How do these unexpected presentations of Nancy Spero’s images critique the spaces that they are in?

- How do the exhibition tactics add meaning to Nancy Spero’s prints and textile?

- Tie your answers to what you have learned about Institutional Critique in this chapter.

Focus: Wangechi Mutu at the Legion of Honor

Wangechi Mutu (born 1972) is a Kenyan-born contemporary artist who, like Nancy Spero presented above, is also not immediately associated with Institutional Critique, though her work in film and performance connects her work to contemporary New Media Art. However her 2021 exhibition “Wangechi Mutu: I Am Speaking, Are You Listening?” engaged in a critical dialogue with Western Art History as an institution. The work in the exhibition was commissioned specifically for the Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco, where it was displayed and it featured sculptures, collages, and a film embedded in the galleries and museum courtyard.

In the main courtyard and many of the gallery rooms, Mutu posed questions about the museum’s collections and the connections between Western Art History, power and oppression. She infuses (or invades) the museum with Afrofuturist / Posthuman beings that propose new mythologies countering Enlightenment and Western Christian narratives that hide the realities of colonial violence. A violence often obscured by art history. Mutu’s work critiques the history of colonization in Africa, especially in her birth country of Kenya, and additionally speaks to the oppression of Black women in the United States where she currently lives.

Look & Reflect: Wangechi Mutu

As you look at the work in “Wangechi Mutu: I Am Speaking, Are You Listening?” the 2021 exhibition installation at the Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco, address the prompts below.

You can also watch this short film made in conjunction with the exhibition and takes viewers on a tour through Wangechi Mutu’s work dispersed throughout the Legion of Honor Galleries. Mutu narrates this film and it was directed by Dawit N.M. (9:30 minutes).

Questions to Consider:

- Discuss the meanings created when her art is exhibited in this way, woven throughout the galleries of European art.

- What aspects of the Museum does her work critique? Give examples of when this critique is the strongest.

Key Takeaways

By working through this chapter, you will begin to:

- Define Institutional Critique in art, especially as it relates to the public art institution.

- Understand how Institutional Critique is connected to Conceptual Art.

- Explain how works of Institutional Critique exhibit some elements of New Media Art.

- Recognize Institutional Critique in a variety of art media and practices

Selected Bibliography

Alberro, Alexander and Blake Stimson, eds. Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings. MIT Press, 2011.

Ekeberg, Jonas, ed. New Institutionalism. Oslo: OCA/verksted. 2003.

Fraser, Andrea. “From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Cri-tique“. Artforum. September 2005.

Ginsberg, Elizabeth. “Case Study: Mining the Museum.” Beautiful Trouble: A Toolbox for Revolution. Accessed 2/25/21.

Harris, Dr. Beteh, Sal Khan, and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Hans Haacke, Seurat’s “Les Poseuses” (small version), 1884-1975,” in Smarthistory, December 9, 2015.

Paul, Christiane. “New Media Art and Institutional Critique: Networks vs. Institutions.” intelligent agent.com. 2006.

“Return of the Whipping Post: Mining the Museum.” Maryland Center for History and Culture. 2013.

Shiekh, Simon. “Notes on Institutional Critique” do you remember institutional critique? transversal. January, 2006.

Steyerl, Hito. “The Institution of Critique“. do you remember institutional critique? transversal. January, 2006.

Welchman, John C. Institutional Critique and After. SoCCAS Symposium Vol. II. JRP Ringier. 2006.