2 Visual Analysis and New Media Art

What is Visual Analysis?

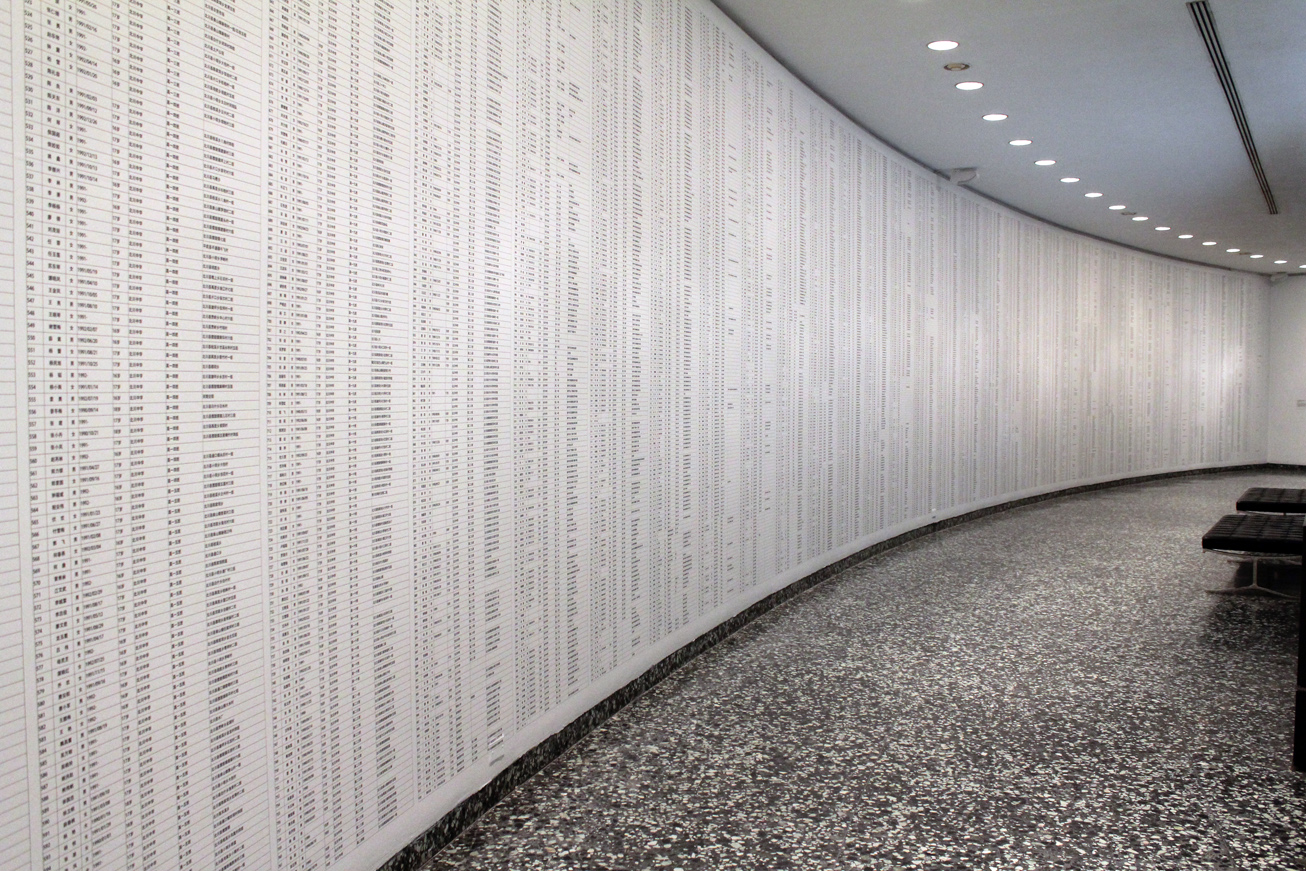

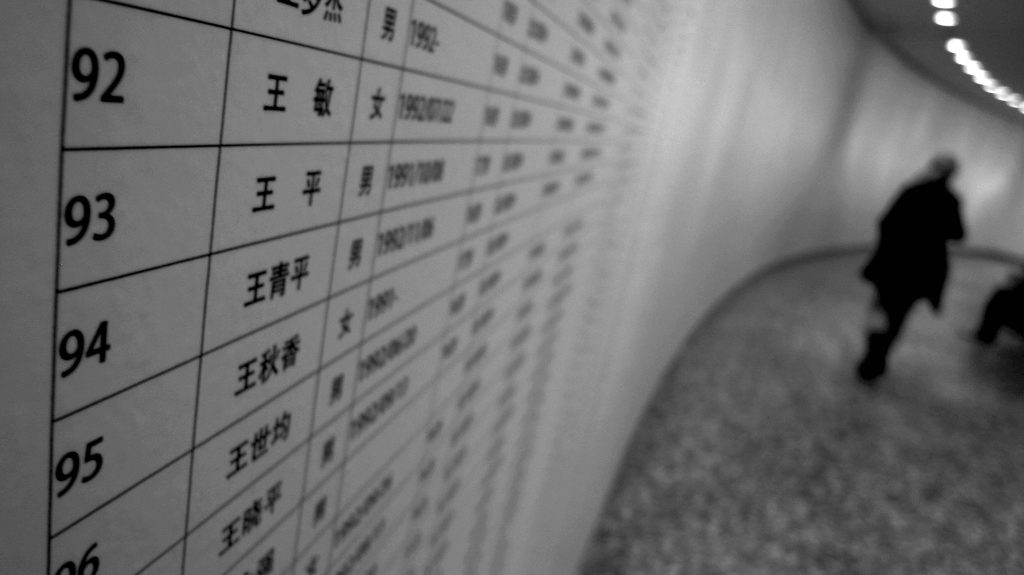

Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens’ Investigation (2008 – 2011) is a large-scale inkjet print by artist and activist Ai Weiwei (born 1957) mounted to the walls of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. in 2012 for the exhibition “Ai Weiwei: According to What?” The print has been exhibited similarly in other art exhibitions around the world since then as a work comprising 21 scrolls measuring in total 10 ½ feet tall and over 42 feet long. The print depicts the names, ages, and birthdays of over 5000 children killed in sub-standard, government-built schools in the earthquake that hit the Sichuan Province in China in 2008. The names were collected by a group of volunteers organized by Ai Weiwei who were angry that the government did not acknowledge the deaths, destruction, loss, and grief of its citizens. The print is accompanied by Remembrance (2010, 3:41:25 run time), voice recording of the names read by thousands of participants. Participants shared in the work by recording their voices, delivering them via the internet to the project. In this installation, qualities of scale, line, and repetition impact viewers’ experiences and add to meaning in the work.

The viewer is immediately struck by the scale of the work. Stretching floor to ceiling in height, a scroll unfurled along the length of a long wall, the print forces the viewer to step back to take in the magnitude of the work, then move forward and along the wall to view the small characters and numbers transcribed into a grid covering the print.

The actual lines of the grid, thin black lines repeated over and over, stretch the length and height of the wall and give the viewer visual cues for reading and moving through the work. The implied lines of the names and birthdates listed in Chinese characters translated into English alphabet and numbers in graph format emphasize the vertical height and the horizontal sweep of the wall. These implied lines add to the impactful scale and allow viewers to visualize in names the thousands of children killed.

The visual repetition of name after name in the inkjet print is emphasized in Remembrance by the audio repetition of thousands of readers speaking, one after the other, the names on the wall. Repetition of name after name of children killed in the earthquake creates a poignancy that reflects the tragedy and stirs urgency for justice and respect for the grieving families impacted.

This nonrepresentational work, grounded in the traditions of Chinese writing and calligraphy, is produced and presented in materials, methods, and genres of New Media Art. Ai Weiwei used the strategies of Social Practice in art to bring together volunteers in China to research and collect names, interview families, and compile names. He recruited other participants around the world to speak the names. Ai prints the grid of names using the contemporary technology of an inkjet printer, and he employs the internet, platforms like Twitter, and digital technology of audio recording as tools for his work. The scale and scope contribute to a memorial work of art that addresses collective trauma and collective grief.

The introductory paragraphs here visually analyze Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens and Remembrance by Ai Weiwei. The works are firstly introduced and described. A close look at visual elements of line and principles of design of scale and repetition show the impact on the viewer and ways that the work creates meaning, including the ties to materials and genres of New Media Art here. Looking at and experiencing what is traditionally called “formal” elements of art is like learning the key words of a new language. Using these “key words” in visual and experiential analysis is speaking the language of art.

In this chapter, you will be introduced to the vocabulary of art in order to help you look at, talk about, write about, and even make art. The focus will be practicing analysis of art made with materials and processes specific to New Media Art. When you develop this analysis with the Elements of New Media Art explained in the Introduction to this resource, you can offer rich interpretations of works of art.

Stop & Reflect: What is Visual Analysis?

- Consider the analysis above. What are the challenges of analyzing the form of a work of art that you can’t see in person? How do the two photographs and the writing provide slightly different ways of engaging with the work?

- Some New Media Art by nature of its medium (materials), processes and techniques, or conceptual approaches are challenging to analyze visually. What are some of the challenges when trying to describe and analyze a work of art when all you have is photographic documentation and you weren’t there? You will experience this challenge throughout this text, for example in the chapter on Performance Art.

- Ai Weiwei’s work touches on a number of genres explored in this book. Look at the chapters listed in the Contents of this book. Anticipating your read and what you already know about New Media Art, how would Ai Weiwei’s work fit into some of these chapters? For example, how do you think his work is a good example of Social Practice in Art?

The three main ways to tackle a work of art are (and best in this order)

- Describe the work of art.

- Analyze the work of art using the terminology of form and design.

- Interpret the work of art.

Viewers have a tendency to jump right into interpretation when analyzing art. Stepping back and describing and analyzing for your reader or audience (before interpreting) will lend validity to your reading of the work of art.

Firstly, describe the work of art

Imagine that your reader is not able to see the work of art you wish to analyze. Start by describing as if you are telling them over the telephone (rather than showing them over video!).

Introducing the basics

Introduce the work of art with the basic archival information that you know. For example, in this text and in other books, you can often find this information in the caption below the image. In a museum, you may find it in the wall text on a plaque next to the work of art. In an art gallery, the information may be available at the front desk.

- name of the artist

- title of the work

- date it was created

- size – you can describe the relative or approximate size or give the exact measurements of the art object. Measurements should be listed in this order: height x width x depth. If you are not writing about an object, you can express size in other ways, like the length in time of a film.

- media or materials used to make the work

- location of the work

Note stylistic aspects

Study the work and think about a general way to describe it to someone who can’t see it. Is this work representational or nonrepresentational? Is it expressive or not so emotive? What is the subject matter? Address the basic stylistic aspects of the work:

- Representational art attempts to depict the external, natural world in a visually understandable way. The following can describe representational art:

- realistic — depicted as in actual, visible (often social and political) reality

- naturalistic — resembling physical appearance

- idealized — shown in perfection as in prevailing ideals of the culture

- stylized — conforming to an intellectual or artistic idea rather than to naturalistic appearances; stylized images may consist of shapes that would symbolize or suggest a represented object.

- abstract — natural forms are not rendered in a naturalistic way but are simplified or distorted to some extent, often to convey the essence of the object or idea. Abstract art can contain some elements of representation or can be nonobjective

- Nonrepresentational or nonobjective art does not reproduce the appearance of objects, figures, or scenes in the natural world. Nonrepresentational art can be composed of lines, shapes, and colors, all chosen for their expressive potential.

- Expressionistic art – containing exaggeration of form and expression; appealing to subjective response. Both representational and nonrepresentational art can have expressive qualities defined by visual elements. Expressionism is often a characteristic in different styles and art movements of Western Art History, like Romanticism, German Expressionism, Abstract Expressionism, and Neo-Expressionism.

Stop & Reflect: Stylistic aspects

- As you explore other chapters in this book, ask yourself how you might apply these terms to different examples of New Media Art. For example, how is the early experimental film by Hans Richter (Rhthmus 21, 1921/1923) a good example of nonrepresentational art?

- Expressionism is often a characteristic in different styles and art movements of Western Art History, like Romanticism, German Expressionism, Abstract Expressionism, and Neo-Expressionism. In these, paintings may have loose, textured brushstrokes or bold, unexpected colors. How can genres of New Media Art, especially those that rely heavily on new technologies, show qualities of expressionistic art? Try this example of Internet Art (or Net Art) – https://www.jacksonpollock.org

Organize your description

You may describe from foreground to background, outside to inside, left to right, or beginning to end. Use the work of art to help guide your description. Your description could become quite complex and detailed. Try to tackle it in a few sentences and then move into analysis.

Secondly, analyze the work of art

The essence of analysis is your next step:

- identifying visual elements and principles of design and

- explaining the impact of those elements on the viewer or on the work itself.

This takes quite a bit of practice. You will want to return to this chapter as you explore the different genres of New Media Art throughout this text.

A written visual analysis of an artwork contains some, but NOT all, of the following elements. The analysis should contain the elements most pertinent to the art object.

Visual Elements and Form

Formal elements are the purely visual aspects of art. As they impact the viewer, principles of design (below) can be expressed.

For example, read the analysis of this photograph, and see if you can recognize

- introduction and description,

- visual analysis, and

- interpretation.

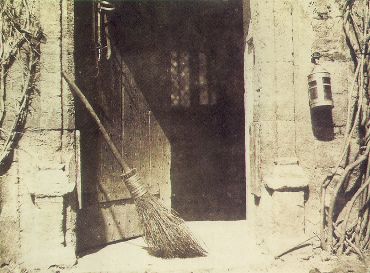

This early photograph The Open Door (1844) by William Henry Fox Talbot was made from a calotype negative for his book The Pencil of Nature. It depicts a straw or twig broom leaning on the doorframe in the doorway of an open door. A lantern hangs on the outside wall to the right of the door. The door is cropped, and inside you can see a faceted window. Line and light are important visual elements in this photograph.

The vertical lines of the carved stone door facing frame the broom and the dark interior space. These lines are echoed in the vertical wooden slats of the door and in the frame of the interior window. The vertical lines create a calm mood and unify the image. The diagonal line of the broom repeated in the edge of the shadow on the door adds energy and interest to the composition. The energetic lines draw our attention to the space in the middle of the composition.

It’s here in the doorway that we see a contrast between the very brightly lit exterior and the dark interior. This contrast also creates interest and piques curiosity about the faint faceted light deeper inside the door.

Both line and light create a focal point and add mystery to this photograph.

Line

You may notice actual (rendered) lines in the work of art and you may also notice implied lines. Line is important in most all discussions of visual elements. Both types of line show movement and direction in the work.

Actual lines can be contour or outlines and/or more expressive lines of force within the object that define the shape and lead the viewer’s eye.

Implied line often relates to overall composition. This is an important element to look for when you analyze. Notice the ways that shapes and figures are arranged in order to direct our reactions. For example,

- HORIZONTAL lines and horizontally arranged compositions are usually very calm.

- VERTICAL lines create the same effect and also exude power (like a skyscraper).

- DIAGONAL lines and compositions arranged along diagonals are much more energetic.

- CURVED lines often express energy as well.

Color

Here are basic color properties that you can consider when analyzing:

- hue – the name of the color (dark red, pale blue, buttery yellow,…)

- value – refers to the degree of lightness or darkness (on the scale from white to black) often created by light source

- intensity or saturation – the degree of brightness or dullness; the purity of the color

Colors can have emotional effects on viewers. Imagine yourself in a red room; now imagine yourself in a blue room. What emotions do the colors evoke?

Light

Since light is a function of New Media Art processes like photography and filmmaking, if is often important to explain the impact of light in the art work. Analyses of architecture should always comment on the use of light.

Light is used in other art to create a sense of perspective and depth and/or emphasis within a composition.

Chiaroscuro is the use of light and dark to depict the volume of a figure on a two-dimensional picture plane. An artist uses chiaroscuro to represent light falling across a curved surface ultimately showing the illusion of three-dimensionality of that surface. Chiaroscuro is often pointed out in drawing and painting, though you may see examples of it in Printmaking.

Spatial qualities

Mass and volume is expressed in three-dimensional art objects.

Mass is three-dimensional form, often implying bulk, density and weight.

Volume is similar to mass, but volume can also be void or empty or suggest an enclosed space.

Three-dimensional space is the space that our bodies occupy. Sculpture and architecture and other objects with mass exist in space.

- When analyzing architecture, always think about space: interior spaces, exterior spaces, and how you might experience or be directed through a space.

- When analyzing sculpture, consider the space which it occupies.

- With New Media Art, consider the architectural or sculptural qualities and how they may construct and define space.

Implied or represented space explains how a three-dimensional world is represented on a two-dimensional picture plane

Pictorial depth (spatial recession) often relates to the foreground, middle ground, and background represented in a picture. There are several devices for showing pictorial depth:

- overlapping

- diminution

- vertical perspective and diagonal perspective

- atmospheric perspective

- divergent perspective, isometric perspective, and intuitive perspective

- linear perspective (one-point & two-point)

- foreshortening

Positive and negative space are often discussed together.

- negative space (unfilled) – Negative space is often as much a part of the work as its positive space, especially in sculpture.

- positive space (solids)

Texture and pattern

When discussing surface quality, draw on those adjectives related to texture: for example, smooth, polished, rough, coarse, oily.

- texture of the actual surface of artwork

- texture of object represented

- Pattern is a repetitive motif or design that may add a visual texture.

Time and motion

Artists use visual elements and principles of design to depict time and motion in art. Pay attention to the ways that time and motion are expressed. Film- and video-based media are founded on qualities of time and motion. Time is an underlying quality in many of the Elements of New Media Art. You will want to circle back to expressions of time as you look at art in this book.

Stop & Reflect: Visual Elements and Form

- Chiaroscuro is often pointed out in drawing and painting, though you may see examples of it in printmaking. In the Printmaking chapter, look at the etching by Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait with Saskia, 1636. How does he express chiaroscuro using hatching and cross-hatching? Point to details of light and dark in the print, and explain how chiaroscuro makes the figures in this two-dimensional work appear three dimensional.

- Jump to the section of this book that discusses 3D printing. How do the sculptures by Morehshin Allahyari both express and challenge your sense of mass in the works? Point to details in one of the sculptures to help explain.

- Think about three-dimensional space when you look at Installation Art. Choose one example of Installation Art, and explain how the work uses or directs space to create meaning.

- How do artists making Light Art use light to create a sense of three-dimensional space? Point to an example, and imagine your perception and misperception of space.

- Look at Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) in the section of the book called Earthworks. Discuss the contrasts of textures in this work, and their impact on the viewer or visitor who walks the spiral in the actual landscape. Point to details and use adjectives to describe different textures.

- Return to the Introduction and the explanations of the Elements of New Media Art. What are the nuances of time in different types of New Media Art? You will be able to answer this question more deeply as you read further in this text.

Principles of Design

Balance

- Symmetry – two halves of a composition correspond to one another in terms of size, shape, and placement of forms. The implied center of gravity is the vertical axis (an imaginary line drawn down the center of the composition). Symmetrical balance often lends a sense of stability to the work asymmetrical balance – balance achieved in a composition when neither side reflects or mirrors the other. This is usually achieved by a balance of the visual weights of forms and spaces represented.

- Asymmetrical balance often lends a sense of dynamism to the work.

Emphasis and focal point

Artists manipulate line, color, scale, placement, and light among other elements to create a focal point in a work. Note the focal point in works of art. Often, though, there is no single point that is emphasized.

Scale and proportion

- scale – size in relation to a standard or “normal” size and/or in relation to the objects around it

- proportion – relationship between the parts of an object; or the relationship of the whole object to its environment

Rhythm and repetition

Think about the way repetition might create a rhythm and the way that these elements contribute to your experience of the work of art.

Unity and variety

Visual elements and principles of design contribute to a sense of oneness (unity) or difference (variety) in works of art.

Stop and Reflect: Principles of Design

- Return to the discussion in the Introduction about Stephanie Dinkins, Conversations with Bina48 (2014-ongoing). How does Dinkins use symmetry in the video presentation of her conversations with Bina48, an intelligent computer? Point to some examples of her play with visual symmetry, and explain how it adds meaning to the work.

- Return to the discussion in the Introduction about Raoul Hausmann, Mechanical Head (Spirit of Our Times), 1919, and the Dada precedent in New Media Art. Explain asymmetry in this sculpture and the impact on meaning and your experience of this work.

- Return to William Henry Fox Talbot’s photograph The Open Door (1844) discussed above. What is the focal point, and what visual elements contribute to this? Point to examples, and discuss how your eye moves through the composition.

- Now, look again at Nam June Paik’s video installation Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska. Hawaii (1995), discussed in the Introduction. Is focal point more difficult to find in this work? Explain the different ways that this work grabs your attention. Why would an artist emphasize focal point in a work? Why would an artist intentionally avoid emphasis in a work?

- Look at Krzysztof Wodiczko’s projection on the Hirshhorn Museum (in the chapter on Institutional Critique). How is scale an important visual element in his work? What meaning(s) does scale create in this work?

- Watch Dara Birnbaum’s video Technology/Transformation/Wonder Woman (1978-1979) in the chapter on Digital Video Art and Video Installation. Point to examples of repetition, and explain how this impacts the work and the viewer. What meanings from the work are made from repetition?

- Artists constantly use unity of a particular visual element to tie the composition or installation space together – to create a sense of oneness. Can you locate a work of art in this text and explain how the artists creates unity in their work? How does unity add to meaning?

- Artists constantly use variety of approaches to a visual element in their work to show a sense of difference or to create interest. Can you locate a work of art in this text and explain how the artist creates variety in their work? How does variety add to meaning?

Medium (media in the plural) and process

As you analyze, it’s also important to think about MEDIUM (material from which an art object is made) and PROCESS.

Questions to Consider before reading further

- How do people make art? List all of the media or processes used to make art that you can think of.

- The medium – or media in the plural – is/are the materials with which the work of art is made. The art processes or techniques are the ways in which the works of art are made, considering the tools and how they are used. Which media and processes that you listed are tied to traditional art practices?

- Which media and processes that you listed are examples of New Media Art? When is it ambiguous or contradictory?

- What connections can you draw between some of these media and processes?

- Look at the lists below, and see how many different media you identified.

- Return to the discussion Traditional Media and New Media in the Introduction. How does this discussion add to your exploration of visual analysis in this chapter? What themes are significant?

These lists name the different media and processes tied to categories of two-dimensional, three-dimensional, and four-dimensional or time-based arts, the New Media Art of this text.

Two-dimensional arts – painting, drawing, printmaking, photography

- Painting – wall painting, illumination (decoration of books with paintings), miniature painting, scroll painting, easel painting

- encaustic, fresco, tempera, oil, watercolor, gouache, acrylic and synthetic media

- painting related techniques – collage, mosaic

- Drawing – sketches (quick notes), studies (carefully drawn analyses), drawings as artworks, cartoons (full-scale preparatory drawings)

- dry media – pencil, metalpoint, charcoal, chalk and crayon

- liquid media – pen and ink, brush and ink

- Printmaking (graphic arts) – images printed or reproduced

- relief printmaking processes – woodcut, wood engraving, linocut

- intaglio printmaking processes – engraving, drypoint, mezzotint, etching, aquatint

- lithography

- screenprinting (silkscreen printing)

- Photographs

Three-dimensional arts – sculpture (cast, modeled or assembled), architecture, ornamental and practical arts

- Sculpture – three-dimensional,

- methods of sculpting – carved (reductive, material is taken away), modeled (additive, built up from material), assembled

- types of sculpture

- Sculpture-in-the-round (freestanding)

- relief sculpture – image projects from surface of which it is a part

- high relief — projecting far off background

- low relief — projections slightly raised

- sunken relief — image carved into surface, highest part of relief is flat

Four-dimensional arts or New Media arts – art that uses or is impacted by aspects of time and/or technology

- ephemeral arts – work changes, disappears, in state of constant change, or must be re-experienced

-

- performance art, earthworks, social interaction

- film, video art, computer art, digital photography, virtual reality, augmented reality

As you continue to explore this textbook, focusing on New Media Art and processes, you will want to include the experiential Elements of New Media Art that are explained in the Introduction.

Thirdly, interpret the work

Content and Context

As you interpret and add content and context to your visual analysis by researching aspects of the work of art, you may go in a number of directions:

- Subject matter – What is represented in the art; or is the subject matter lines and colors if you are analyzing a non-representational work of art?

- Ideas and concepts within work – This is a good time to consider the Elements of New Media Art (in the Introduction) if you haven’t already.

- Social, political, economic contexts – This comes with research and knowledge of art history.

- Intention of the artist – However, we cannot always know this.

- Reception of viewer – Think about the way you as a viewer might experience the art.

- Meaning of the work of art.

Using the language of visual art outlined in this chapter, you need no research or knowledge of art history to discuss art immediately. Think about how much you can do by just describing (firstly) and analyzing (secondly) a work of art! With research, however, you can create a deeper context for the work of art. You can determine styles and explore content. You can learn about the history and time and place in which the work was initially created. You can consider the current context of contemporary viewers and how this changes or enhances meaning. All of this leads to interpretation and contributes to your own thoughts about the work. Don’t feel pressure to interpret works of art immediately. Give yourself time to feel comfortable describing and visually analyzing using this language, the terminology in this chapter, that is very specific to art.

Stop & Reflect: Content, Context, and Interpretation

- Return to the visual analysis of Ai Weiwei’s Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens’ Investigation (2008 – 2011) at the beginning of this chapter.

- Point to examples of description in the writing.

- Point to examples of visual analysis.

- Point to moments in which the author is making interpretation by adding context and explanations of content.

- Return to the description and analysis of William Henry Fox Talbot’s photograph The Open Door (1844) discussed above.

- What interpretations can you make based on the analysis of line and light?

- What other information could you use to interpret more deeply this photograph? What questions would you try to answer in your research?

- Return to the discussion of the Elements of New Media Art in the Introduction, in particular the Readymade. How does Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917/1964) resist visual analysis? Why does Conceptual Art often resist visual analysis?

Key Takeaways

By working through this chapter, you will begin to:

- Learn how to describe a works of art.

- Identify visual elements in art.

- Practice the vocabulary of visual analysis to show the impact of visual qualities.

- Recognize the difference between describing, analyzing, and interpreting works of art.

- Find description, analysis, and interpretation in writing about art.

- Analyze works of New Media Art using both the elements of visual analysis and the Elements of New Media Art presented in the introduction to this text.

Optional: Lesson Extensions

Below you will find more resources about Visual Analysis.

Visual Analysis – general resources

“The Skill of Describing.” Smarthistory. Source: YouTube. (3:43 minutes)

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Art historical analysis: an introduction,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed September 10, 2021 (10:39 minutes).

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “How to do visual (formal) analysis,” in Smarthistory, September 18, 2017, accessed September 25, 2017 (9:52 minutes).

Resources for Elements of Art and Principles of Design

Use the Getty Museum website to help define the “elements of art” and “principles of design” in visual (or formal) analysis of works of art. The Getty Museum also has a good YouTube channel.

- The Getty Museum. “Introducing Formal Analysis: Landscape.” Published 4/30/15. (4:51 minutes) Watch this video that analyzes landscape painting.

- The Getty Museum. “Introducing Formal Analysis: Still Life.” Published 4/30/15. (4:23 minutes) Watch this video that analyzes still life painting.

“Analyzing the Elements of Art.” This “learning blog” from the New York Times gives some good help on analyzing elements of art. They are working to build this, but for now, you can explore

- “Five Ways to Think about Line“

- “Five Ways to Think about Color“

- “Four Ways to Think about Value“

- “Six Ways to Think about Shape“

- “Four Ways to Think about Form“

- “Five Ways to Think about Space“

- “Seven Ways to Think about Texture“

For a more detailed explanation of “color,” see this handout from the National Gallery of Art website.

Visual Analysis specific to Photography

The Getty Museum and Khan Academy. “Exploring photographs through description, formal analysis (visual analysis), and reflection (meaning and interpretation).” Adapted from Exploring Photographs: A Curriculum for Middle and High School Teachers, a curricular publication of the Education Department at the J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007.

Selected Bibliography

Barnet, Sylvan. A Short Guide to Writing about Art. Sixth edition. Addison-Wesley, 2000.

Getlein, Mark. Gilbert’s Living with Art. Sixth edition. McGraw-Hill, 2002.

Sayre, Henry M. A World of Art. Third edition. Prentice Hall, 2000.

Stokstad, Marilyn. Art History. Second edition. Prentice Hall, 2001. Pages 18-23 give a good overview of visual analysis.