8 Digital Video Art and Video Installation

Creating an Immersive Space

You’ve been previously introduced to early film and early video art. In this chapter, we’ll turn to digital video and digital video installation. The artists and artworks in this chapter are presented as individual case studies. Each demonstrates a different aspect of digital video and installation and, together, their works show the medium’s aesthetic and conceptual variation.

Watch & Consider: The Case for Video Art

To give some background on video art using both analog and digital tools, watch a primer on video art from PBS Studio’s The Art Assignment called “The Case for Video Art” (embedded below, 10:01 minutes).

Questions to Consider:

- What makes video art distinct from other forms of moving images?

- How have art and film been intertwined, historically?

- How did the invention of the Sony Portapak affect artists?

- Where do you notice the intermedia qualities of video art? How do these compare to Land Art, Performance, and Social Practice discussed in other chapters?

- According to the video, what does the term expanded cinema mean?

- How does video examine its own existence and creation (think about the focus on exposing the means of production, for example)?

- How does video integrate into life?

- What are examples of public versus private videos?

- Consider the T.V. as a means of both expression and opposition.

- In what ways does video art aid in addressing and exploring identity?

- How has the internet affected video art?

- How is appropriation used in the works by some of the artists in this unit?

Read & Reflect: What is Digital Art?

The readings linked to below will help us further contextualize and define digital art. The concise definition from the Tate Museum focuses on the importance of interaction between the artwork and the viewer, as well as the intermedia qualities of digital video and installation. The essays by Marie Chatel and Kate Horsfield will help us frame digital video and installation within the broader context of video art history. Finally, there are questions to consider at the end of this chapter that specifically address Horsfield’s “Busting the Tube,” which can help guide your reading.

- Tate Terms: Digital Art

- Marie Chatel, “What is Digital Art? Definition and Scope of the New Media” (Medium)

- Kate Horsfield, “Busting the Tube: A Brief History of Video Art” (Video Art Databank)

The Basics: What is Digital Video Art & Installation?

The term digital art, coined in the 1980s, refers to art made, stored, and viewed using digital technology. However, the history of digital art predates the term. Digital art has its roots in Conceptual Art and Fluxus, which you reviewed in the Introduction and artists began experimenting with computer art in the 1960s and 1970s. Pioneers in digital art include the animator John Whitney, Sr. (1917-1995), the organization Experiments in Art and Technology (established in 1967), and the artist Harold Cohen (1928-2016). Practitioners of digital art are interested in the interplay between art and technology.

Stop & Consider: Digital Video

Digital Video defines when digital data is used to create a video, which can be edited by a computer; as opposed to analog video (like the examples you read about in our chapter on Early Video Art), which uses tape to capture each frame.

- Be prepared to compare the analog examples of video art discussed in this chapter with those discussed earlier.

- Also prepare to compare the digital video examples in this chapter to the examples of analog video art you’ve been learning about.

Digital video technology became more accessible in 1986 with the invention of the Sony D1. By the 1990s, digital technologies had improved, and artists could reproduce high-resolution videos, creating an interactive and dynamically changing space. Digital video art and installation are also closely connected to the New Media principle of computability (among others discussed in this chapter) and a desire to manifest an immersive experience for the viewer.

Elements of New Media Art and other Key Terms

As you move through the material keep the following qualities, which characterize digital video and installation, in mind: adaptable, collaborative, computability, and participatory. We’ll apply these qualities, defined below, to the specific examples outlined in the chapter.

- Adaptable: This refers to the flexibility of digital video; video can be projected on the side of a building or on the walls of a gallery space, for example.

- Collaborative: A quality of New Media; as you’ll see, many examples in this chapter rely on collaboration from the viewer/participant. This term also describes works, like Zina Saro-Wiwa’s series that involved participants, in this case people from her home state, in their creation.

- Computability: Some examples in this chapter will show the use of computer algorithms to help create the work of art.

- Participatory: In art, this refers to the viewer becoming an active participant in the work of art; the work is considered unfinished without the viewer’s participation. Participatory and collaborative are very close in their definitions. While both participatory and collaborative art are interactive, the difference is that collaborative art removes control of the work’s outcome from the artist.

Additional Key Terms listed and defined below are used throughout this chapter. Specific examples of artworks from the chapter are indicated when applicable to help illustrate the term.

- Fragmentation: In digital video, this could be a non-linear presentation; the information and/or images are broken up. Think of fragmentation as a digital strategy that breaks apart information/images to explore how visual information is conventionally conveyed.

- Hyperkinetic: When talking about art, this term refers to quick, often abrupt, movements that create a frenzied energy.

- Hypermedia: The Internet is a perfect example of hypermedia; simply defined, hypermedia usually refers to “link media” or “interactive media” and could be a software that connects elements (video, plain text or hyperlink) of a computer system, for example. Information is explored in a non-linear manner (meaning you can click around and don’t have to follow a set path). The opposite of hypermedia would be a linear media, such as a novel. (Hypermedia is an extension of hypertext. See also the discussion of Hypertext in The Digital Revolution chapter.)

- Installation: This term used to describe immersive, large-scale, mixed-media constructions; installations are typically site-specific and often temporary.

- Multimedia: Multimedia describes artworks made from a range of materials and include an electronic element such as audio or video; this is different from intermedia, which refers to an interdisciplinary approach to making art (combining one or more disciplines, like painting and dance).

Setting the Stage: Postmodern Video Art

Before we move on to our examples of digital video and installation, it’s important to take a moment to review the work of Dara Birnbaum (born 1946) and Howardena Pindell (born 1943), two video artists working on the cusp of a changing technology. While Brinbaum and Pindell both create video using analog techniques, their early experiments with video sets an importance precedent for the artists discussed in this chapter. Both artists can be examined through the lens of Postmodernism and their works serve as a bridge between the digital experiments of artists featured later in this chapter, and the artists discussed in our previous chapter, Early Video Art.

Key Term

Postmodern: Beginning in the 1970s, Postmodernism in art follows on the heels of Modernism and can be seen as a reaction against Modernism. Postmodern artists use strategies such as irony, humor, and appropriation to critique and question dominant culture.

Dara Birnbaum

Dara Birnbaum is an American video and installation artist and she was one of the first video artists to explore the use of appropriated imagery in her work. Her video, Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman borrows and re-contextualizes scenes from the popular 1970s TV series Wonder Woman, isolating and repeating moments of transformation (when the “ordinary” woman, Diana Prince, becomes Wonder Woman).

Dara Birnbaum, Technology/Transformation/Wonder Woman, 1978-1979, color video with sound (5:50 minutes). As you watch, pay attention to Birnbaum’s use of appropriation, fragmentation, and repetition.

Fragmentation and repetition are vital strategies Birnbaum uses to disrupt the viewer’s understanding of the images’ sequence. For example, the video begins with a series of repeated explosions, then moves to a shot of Diana Prince, arms stretched out to her sides, spinning around until a fireball explodes. Birnbaum withholds the final act of transformation from the viewer until after several spins in. Later, Prince is shown running, caught in mid stride, over and over again, while the soundtrack to the sequences stutters in the background.

Dara Birnbaum’s work Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman, can also be described as dynamic because of the use of repetition. Dynamic refers to movement and in video art, you can think about how quick the cuts, for example, or how fast (or slow) subjects move or talk on the screen. As you continue to read through this chapter, pay attention to the sense of movement on the screen in each video and how it engages you.

According to the artist: “The stutter-step progression of ‘extended moments’ of transformation from Wonder Woman, the abbreviated narrative — running, spinning, saving a man — allows the underlying theme to surface: psychological transformation versus television product. Real becomes Wonder in order to “do good” (be moral) in an (a) or (im)moral society.” (Dara Birnbaum quoted in Electronic Arts Intermix).

Stop & Reflect: Dara Birnbaum

- What is your reaction to the isolation of explosion images mixed with Wonder Woman’s repetitive actions?

- By remixing a popular television program, Birnbaum sought to turn the TV on itself. As she puts it, in her work, television “is manipulated before it manipulates us.” How does Birnbaum’s video reflect this deconstruction and manipulation?

- Birnbaum originally showed her video in the window of a retail space. How does this display strategy align her work with other examples of New Media you’ve learned about?

- Based on the definition provided in the Key Term box above and what you learned about Early Video Art, can you describe the Postmodern qualities of Birnbaum’s work?

Howardena Pindell

The American multimedia artist Howardena Pindell created Free, White and 21 in 1980 when she was 37 years old; just 8 months after being in a near fatal car crash that left her with trauma and partial memory loss.

Free, White and 21 is part of Pindell’s Autobiography series, which she began in 1980. This series frequently incorporated the artist’s own body as well as personal items, and directly reflects her experiences as a Black woman in America. Pindell credits the creation of this video series with helping her heal from her accident; it also marked a turning point in her subject matter and she has continued to explore the autobiographical in her artwork.

Howardena Pindell, Free, White, and 21, 1980, video (12:15 minutes). Please watch this video in its entirety to see the interactions between Pindell’s two roles.

Pindell’s work is a good example of the term expanded cinema because she faces the camera and speaks directly to the viewer, creating a space for more active participation and engagement. Her work confronts the viewer by implicating us in her trauma, involving us in both her suffering and her healing.

The twelve-minute video features Pindell in two roles—as herself, detailing experiences growing up as a Black woman in America, and as an anonymous white female character (wearing a blonde wig, white powder, and sunglasses) responding to those accounts.

The format is part confessional, with scenes of Pindell speaking plainly to the camera as she recounts subtle and overt instances of racism she, and her mother, experienced from childhood to the present, in all areas of daily life—at school, work, and leisure. These segments then cut to the white woman, who is dismissive of these events, calling Pindell “paranoid” and “ungrateful” while asserting her privilege of being “free, white, and 21,” removed from the racism and inequity Black women constantly face. The figure of the white woman continually discounts Pindell’s traumatic experiences with statements like, “you won’t exist until we validate you.”

Interwoven through these exchanges are views of Pindell wrapping and then unwrapping her head with white bandages and peeling off a facial mask, perhaps both a reference to Pindell’s accident and how racism exists in both overt and covert ways.

The work also references the tensions between Black and white feminists in the 1970s, when feminism oriented around the idea of “woman” as white, cis-gendered, and middle class. As a Black artist, Pindell struggled to find venues who would exhibit her work. She recalls in The Howardena Pindell Papers (Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago):

I decided to make Free, White and 21 after yet another run-in with racism in the art world and the White feminists. I was feeling very isolated as a token artist. I found that White women wanted me to be limited to their agenda…. I was told I was jealous because I noticed and talked about it. Racism, as a constant assault in the daily lives of all people of color, was not a high priority for them…. It was about domination and the erasure of experience, canceling and rewriting history in a way that made one group feel safe and not threatened…. In the tape, I was bristling at the women’s movement as well as at the art world and some of the usual offensive encounters that were heaped on top of the racism of my profession.

Video is only a minor part of Pindell’s artistic output. She also paints, writes, and produces collages and prints. She’s known for her labor-intensive processes, such as gluing tiny bits of hole-punched paper onto canvases. She also worked for 12 years at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA), after graduating from Yale with an MFA; she left MoMA when her efforts to draw attention to and push against institutional racism in the museum field were discouraged and ignored. You can read more about Pindell’s experiences in her own words by visiting her digitized papers at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (optional, but a fantastic resource).

Stop & Reflect: Howardena Pindell

- After viewing Free, White, and 21, how does Pindell merge her roles as narrator, actor, and artist? Do these roles ever intersect or overlap in the video?

- What is the power of testimony in Free, White, and 21? How do words and moving images connect in Pindell’s work to engage and even implicate the viewer in the artist’s testimony?

- Based on the definition provided in the Key Term box above and what you learned about Early Video Art, can you describe the Postmodern qualities of Pindell’s work?

Case Studies: Digital Video Artists & Artworks

A reminder that the examples in this chapter are presented as case studies. They are organized chronologically and demonstrate the variety of approaches to digital video. As you review these case studies, keep in mind the Postmodern approach of Dara Birnbaum and Howardena Pindell, as well as the key terms outlined at the beginning of this chapter. Wherever possible, a video excerpt of the work is embedded so you can see it in action; additional optional resources are also provided under each video for further learning.

Focus: Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau, A-Volve

Christa Sommerer (born 1964) and Laurent Mignonneau (born 1967) are two artists who have collaborated since 1992 on digital projects, such as custom coded interactive artworks. Their work often explores the interaction of biology and technology.

Read & Listen: Sommerer and Mignonneau

- Read about Sommerer and Mignonneau’s work at the Digital Art Archive website.

- You can also read their artist statement to better understand their approach to the work and the ideas they wanted to explore.

- Listen to the artists discuss their work at Media Art Net (2:59 minutes). Here, you can also view a brief slideshow of the piece.

In A-Volve, participants design their own organism using a touchscreen in the gallery space. This invented organism is then “released” into a pool of water where it moves around and interacts with creatures created by other viewers. Visitors can reach into the water to try to touch and catch the moving virtual creatures as they move around; the creatures, in turn, react to the visitors’ movements in real time. A-Volve plays on the concept of “survival of the fittest” as organisms die if they aren’t interacted with regularly (Digital Art Archive).

Thinking back to our key terms, A-Volve is dynamic because it moves and changes in real time; it is also interactive, participatory, and collaborative because the viewers can “touch” the organisms they design and they also contribute to the actual creation of the work of art.

Stop & Reflect: A-Volve

Watch this short video of Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau’s, A-Volve, 1994-1995, an interactive computer installation (3:13 minutes)

Questions to Consider:

- Consider how the work explores real and “unreal” environments. For example, the organisms are virtual, but the interactions visitors have with them in the water, and with each other, are real.

- What is the effect on the viewer as the worlds of biology and technology collide and interact in A-Volve?

- Can you form an interpretation of the artwork based on what you’ve learned about it?

Focus: Camille Utterback, Text Rain and Entangled

American artist Camille Utterback (born 1970) uses digital technologies to create interactive installations, such as Text Rain, that rethink how viewers experience and interact with art. An innovator in digital and interactive video art, Utterback actually began her studies in art as a painter. Her work is very interactive and she creates projects that track viewers’ movements, transforming this information into evolving projections. She is interested in blurring the boundaries between physical and virtual worlds, as well as in exploring the interactions of the body and digital systems. Utterback writes her own code, or computer algorithms (a series of rules) that dictate the changes in her artwork.

In Text Rain, the animated type the participants interact with is a poem called “Talk, You” by the poet Evan Zimroth. By combining poetry and an interactive digital installation, Utterback creates an intermedia experience for the viewer and alters the way a reader typically approaches a poem.

Watch & Consider: Text Rain

Watch a brief interview with Utterback on the MacArthur Foundation website (she was a 2009 MacArthur Grant recipient). (2:28 minutes)

Questions to Consider:

- Utterback refers to her work as reactive sculptures, implying that they respond to participants’ actions. After viewing her work, how would you describe the “reactive” qualities of Text Rain? What does the work react to?

- Can you imagine yourself experiencing Text Rain?

- What do you think it would feel like to be immersed in this digital installation?

- How do text and body interact in Utterback’s piece? An artist we’ll examine later in this chapter, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer (born 1967), also uses text in his digital installations. How would you compare and contrast their strategies?

This next example we’ll examine is Utterback’s work, Entangled. (Featured in the video below installed at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in 2015). In this installation, participants interact with imagery projected onto two sides of a set of translucent scrims – a scrim is a thin screen used a lot in theater – which hang in the center of the space. Movements in the interaction areas on each side of the scrims cause imagery to appear, move, and disappear on the corresponding side’s projection.

When participants’ motions are traced onto both sides of the scrims, a shifting visual apparition emerges. The imagery projected from each side of the installation bleeds through the scrims, merging into a shared visual surface. The light catching on both sides of each layer of fabric creates a tangible perceptual depth and volumetric complexity, not typical of projection surfaces.

Watch & Consider: Entangled

Watch 58 seconds of Camille Utterback’s, Entangled, 2015, dual channel interactive installation on scrims; custom software, computer, two cameras, two projectors, two theatre lights, three fabric scrims.

Please watch the video below, which shows Utterback explaining her work, Entangled, and shows it in action at Emerson College Urban Arts Gallery (2:47 minutes).

Questions to Consider:

- How might designing a two-sided piece, like Entangled, be different from designing a similar artwork on a flat, one-sided screen? How does this impact the depth, texture, and use of positive and negative space in the painting?

- As you watch the artwork, think about how it changes? Note any patterns of cause and effect that you notice.

- What do you notice about the colors, marks, and positive and negative space that is being created by movements?

- How do Text Rain and Entangled compare? How are they alike? How are they different?

Utterback’s digital video installations connect to several of the key terms identified at the beginning of this reading. Her work is adaptable, collaborative, and programmed through the use of algorithms (computability). Its presentation is also dynamic, fragmented, collaborative, and participatory. Through her digital installations, Utterback creates a social space, designed to encourage interaction and engagement with the piece, the surroundings, and each other.

Key Terms

- Expanded Cinema: Artists working in digital video and installation often explore how to create an active, rather than passive, space between the screen and the viewer. This can be achieved through the use of multiple screens, as we see in Camille Utterback’s work, as well as through the presentation of film in nontraditional venues, which you read about in the chapter on Early Film and Animation.

- Reactive Sculpture: This term is used specifically by Camille Utterback to differentiate her installations from static sculpture; instead, her work reacts to visitors in the gallery or museum space. (We can also use this term to describe A-Volve by Sommerer and Mignonneau.)

Focus: George Legrady, Pockets Full of Memories

George Legrady’s (born 1950) Pockets Full of Memories maps the relationships between objects. The viewer digitally scans a personal object and describes it by answering a set of questions. An algorithm then classifies that object based on similar descriptions. What you see on the screen is the data the work collects and the possible ways objects relate.

This user-generated archive had an accompanying website when the work was first produced in 2001. This website is no longer accessible, demonstrating one of the difficulties maintaining digital art.

Stop & Reflect: Pockets Full of Memories

Read about Legrady’s work at Media Art Net

Then watch this video showing Legrady’s, Pockets Full of Memories, 2001, digitized image data. (2:57 minutes).

- Optional: In addition to the video embedded above, you can watch the piece in action on Media Art Tube (no sound, 2:50 minutes).

Questions to Consider:

- Looking over the qualities of digital art outlined at the beginning of this chapter, which would you apply to Pockets Full of Memories and why?

- Compare and contrast this work with A-Volve. Think about how each work is adaptive. Do the works interact differently with the viewer?

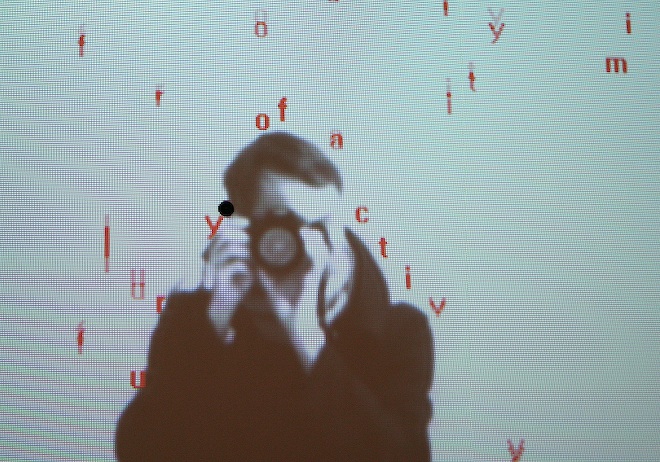

Focus: Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Subtitled Public

Stop & Reflect: Subtitled Public

- Read about Subtitled Public on the Digital Art Archive, where you can also view still images of the installation.

- Read about the work on the Tate Museum’s website, where there is an excerpt from an interview with the artist and analysis from curators and art historians.

- Read more about Rafael Lozano-Hemmer in the Immersive Technologies Chapter. (Coming Soon.)

Watch this short video of Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s, Subtitled Public, 2005, interactive computerized projection, installed at Bitforms Gallery, 2005. (4:24 minutes)

Questions to Consider:

- How do text and body interact in Lozano-Hemmer’s digital installation?

- What role do tracking and surveillance play in Lozano-Hemmer’s work?

- How would you feel entering this digital installation? How do you imagine your experience of this space to be?

- Try to connect Lozano-Hemmer’s work to the vocabulary presented at the beginning of this reading. What terms can you apply to his digital video installation?

- Compare and contrast this work with Text Rain. How is text central to the overall experience of each artwork? What is the effect of each work’s ability to adapt and interact to the visitor’s presence?

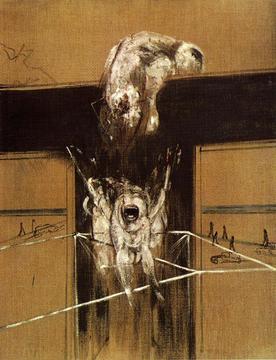

Focus: Paul Pfeiffer, Fragment of a Crucifixion and Caryatids

Paul Pfeiffer (born 1966) is an American artist whose work investigates how mass media shapes our perceptions of events. A key term to understand with Pfeiffer’s work is appropriation or the strategic borrowing and re-contextualization of found media into a work of art. In Fragment of a Crucifixion (After Francis Bacon), Pfeiffer uses appropriated video footage of a moment of mid-game triumph for the Knicks forward Larry Johnson, which he loops so you see it over and over again.

Listen & Watch: Paul Pfeiffer

- Listen to the artist discuss Fragment of a Crucifixion (After Francis Bacon) via the Whitney Museum of American art.

- Watch the Art21 video, embedded below via Vimeo, “Paul Pfeiffer in Time” (12:14 minutes)

https://vimeo.com/20635019

Pfeiffer is especially interested in sporting events because of the spectacle of the game. He digitally manipulates footage, often by isolating, or even erasing the athletes, to comment on a culture obsessed with sports figures and celebrity. What happens, like in Fragment of a Crucifixion (After Francis Bacon), when the player is left alone on the court? His teammates and opponents have all been erased and the viewer only sees Larry Johnson moving, stutter-step, back and forth on the court, flashbulbs blinking sporadically in the stands surrounding him. There is also an audio component as the viewer hears the roar of the crowd, expressing their collective adulation that Johnson has just landed the shot. The repetitive roaring transforms the excitement of the crowd into a sound of alarm or horror.

Fragment of a Crucifixion, pictured above, by Francis Bacon is an unfinished painting from 1950, showing an animal (?) engaged in a struggle with an unformed monster (some historians say this is a chimera) on what looks to be a wooded cross. There is a sketchy scene with cars and people in the distance, right below the blue line.

Through his editing process, Pfeiffer creates seemingly endless moments that direct the viewer’s attention to singular details rather than the original contexts of the images. If we compare Pfeiffer’s digital video work to Bacon’s painting, a sense of tension is revealed between a feeling of triumph and one of misery.

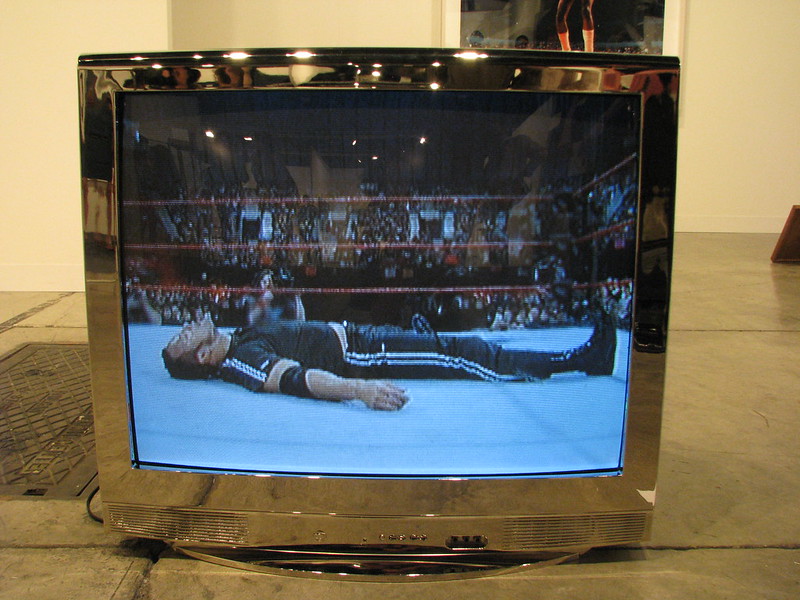

A second work by Pfeiffer that we’ll take a look at is called Caryatid (Hockey). In this version of the Caryatid series, Pfeiffer presents video footage of the Stanley Cup (hockey’s biggest prize), as it is held up above the heads of the winning players. By erasing the players, Pfeiffer alters our perception of hockey’s highest symbol of achievement. Here, the massive cup floats alone above the crowd, unmoored. Inscribed each year with the names of winning players, coaches, managers, and club staff, winning the Stanley Cup is a dream of every aspiring hockey player. Pfeiffer’s manipulation of this footage not only illustrates the Cup’s status as a symbol of a spiritual quest but also meditates on the complicated ways in which faith and desire unfold in contemporary culture.

Watch & Consider: Caryatid

To gain an understanding of this work in context, please click on the link below to a New York Time’s video resource:

- Paul Pfeiffer’s Caryatid (New York Times, 0:32 seconds)

- As you watch the clip, notice how the work is displayed and the small scale of the television monitor.

Above is an installation view of Caryatid (Wrestling), 2009 at Carlier Gebauer, Art Basel. Notice how the television set is placed directly on the floor, instead of elevated to the viewer’s eye level. By forcing the viewer to crouch down to view the work, Pfeiffer creates a more intimate relationship between artwork and audience. He also prefers to use smaller projection mechanisms, such as the television set pictured, to foster this sense of intimacy. Paul Pfeiffer uses the term Video Sculpture to describe the sculpturally-based digital videos he creates; the idea of sculpture is more in the presentation of Pfeiffer’s work, since he often places technology, like a television set, up on a plinth or support typically reserved for sculpture in the museum setting.

In ancient Greek architecture, a caryatid is an architectural support where the figure of a woman takes the place of a column (seen, for example, on the Porch of the Maidens from the Erechtheion Temple on the Acropolis in Athens, which is pictured below). As you can see from the ancient Greek example, the figure looks to be holding up the temple’s entablature with her head. According to Greek mythology, caryatids carried sacred objects on their heads to be used by the gods during feasts.

If you examine the installation view of Caryatid, above, and Fragment of a Crucifixion (After Francis Bacon), you can see what Pfeiffer means when he calls his works video sculptures. Instead of being projected on a large screen, or scrim, creating a large-scale immersive environment, Pfeiffer’s works are often presented at a much smaller scale, creating greater intimacy with the viewer. Whether placed directly on the floor, or presented up on a plinth, or stand, and covered in a vitrine (the clear box that sits over the object), keeping with the tradition of how sculptures are displayed in museums, Pfeiffer calls attention to the intermedia quality of his work and intentionally combines video, sculpture, and sound.

Stop & Reflect: Caryatids

- Why do you think Pfeiffer titled his work, Caryatid, after the ancient architectural feature?

- How does his work subvert the popular, commercialized image of the athlete?

- Why do you think Pfeiffer uses sporting events and athletes as his subject matter?

- Even when the athletes are removed from his videos, what iconography (or symbols) of the event remains?

- Why do you think Pfeiffer prefers a more intimate display for his videos?

Focus: Zina Saro-Wiwa, Table Manners and Karikpo Pipeline

Zina Saro-Wiwa (born 1976) is a Nigerian artist currently based in Brooklyn, NY. She creates work that reflects Nigeria by showcasing the lush verdancy and cultural richness of her homeland, seeking to reject the dominant Western narrative of Nigeria as only an oil-rich, yet environmentally depleted country. Though there has been vast environmental destruction of the Niger Delta by oil companies, much of Saro-Wiwa’s work focuses on the people who live in her home state of Ogoniland, which is in the southwestern part of Nigeria near the coast.

Her father was the renowned writer, human rights and environmental activist, Ken Saro-Wiwa (1941-1995), who was murdered by the Nigerian military dictatorship in 1995. Zina Saro-Wiwa, who prefers the term “culture-worker” instead of activist, believes artists can evoke powerful change through their artwork, just as her father did through his political and social activism. Prior to creating digital videos, Saro-Wiwa was a documentary filmmaker.

After living and going to school in England, Saro-Wiwa made her way back to Ogoniland, Nigeria, for a two year and a half stay. This long visit inspired the ongoing series of digital videos, Table Manners, which the artist began in 2014. Table Manners shows people from the Niger Delta while they are eating. The titles of the works are very straightforward; taken from the name of the person who is eating and the food they consume. As the series has progressed, the subjects are recorded eating snakes and other animals that appear in local folk tales furthering the connection between food and culture.

Watch & Consider: Table Manners

Watch these two short clips from Saro-Wiwa’s series Table Manners:

Zina Saro-Wiwa, Felix Eats Sorgor Salad with Palm Wine, from Table Manners, 2014-2016, digital video (clip, 00:52 seconds).

Zina Saro-Wiwa, Grace Eats Garden Egg with Groundnut Butter, from Table Manners, 2014-2016, digital video (clip, 00:49 seconds).

Optional: Listen & Consider: Zina Saro-Wiwa interview

Listen to a conversation with Zina Saro-Wiwa and Tyler Green on the Modern Art Notes Podcast from September 24, 2015 (1:01:43 hours)

Saro-Wiwa is interested in the symbolism of nourishment, the condition of the places that grow the things we eat, and how food preserves culture. She sees Table Manners as a way to highlight the fertile and dynamic landscape of Nigeria, particularly the Niger Delta where there is still a vibrant fishing and farming community. In doing so, Saro-Wiwa seeks to craft a narrative that is separate from the devastation of decades of oil extraction in the region.

In an interview for the exhibition Landmarks at the College of Fine Arts, The University of Texas, Austin, Saro-Wiwa said:

Nothing is more immediate than food, than the act of nourishing the self. I have found working with food the most strangely powerful and useful way to subvert and renew the conversation about the Niger Delta which defaults to this very circular, bleak hand wringing which has led to very little change or insights into who we really are as a people and how to transcend our predicament. Food has been my portal to accessing something elemental and mysterious but generative and powerful. And the way art reframes an idea or a place is often the embryo for change.

Let’s connect Saro-Wiwa’s work back to the terms presented at the beginning of this chapter. Her work is a great example of collaboration; her subjects are entirely in control of the pace of their meal and what they choose to eat and wear for the video. You could argue her work is also dynamic because the viewer feels a sense of connection with the subject, as if they are sharing a meal with them. This dynamic is reinforced through the installation of the work, pictured below.

Watch & Consider: Karikpo Pipeline

Follow the links below to view clips of this video installation to get a sense of the effect of the five different channels:

- Karikpo Pipeline (via Facebook, 0:56 seconds)

- RCA Dyson Gallery Installation of Karikpo Pipeline (via Facebook, 1:52 minutes)

Above are stills and an installation view from another digital video installation by Saro-Wiwa called, Karikpo Pipeline, 2015. This is a multi (5) channel installation that takes the viewer on a journey through signs of the aging, and now discarded, oil extraction infrastructure in Ogoniland. These old roads, wellheads, and pipelines are superimposed with the images of male dancers performing the Karikpo masquerade. Dancers masked and moving like antelopes traverse this landscape with acrobatic agility, calling attention to the visible and invisible signs of the environmental impact of the oil industry on the Niger Delta.

Stop & Reflect: Zina Saro-Wiwa

- Saro-Wiwa calls herself a “culture worker;” how does this term reflect how she presents the people, culture, landscape, and traditions of the Niger Delta?

- How does Saro-Wiwa’s work assert the humanity of the Ogani people?

- What aspects of Nigerian culture and community does Saro-Wiwa’s work showcase?

- How does her work celebrate her Nigerian culture? How does it critique stereotypes of West Africa?

Focus: Rachel Rose, Everything & More and Lake Valley

Rachel Rose (born 1986) is an American artist known for her immersive digital video installations. Her work explored how our changing relationship to landscape has shaped storytelling and belief systems. Rose draws from and contributes to a long history of cinematic innovation, and through her subjects—whether investigating cryogenics, the American Revolutionary War, modernist architecture, or the sensory experience of walking in outer space—she questions what it is that makes us human and the ways we seek to alter and escape that designation (via Carnegie Museum of Art).

According to the artist, Lake Valley, 2016 explores childhood. Though we can’t currently watch the entire video online, you can notice through video clips and stills how Rose creates an illustrative, textural effect in her work.

The surface quality of each element in the video is important to the emotional resonance of the story. Rose achieves each form’s unique texture by reimagining its surface (the flowers, for example, are made of paper). This creates a sort of collaged quality to the work, and lends a handmade feel to the digitally produced images.

Watch & Consider: Rachel Rose

To acquaint yourself with the artist and her work, watch the video “Rachel Rose Interview: Between Living and Non-Living” via the Louisiana Channel (16:36 minutes), which is embedded below. In this video, Rose discusses four of her video works. Please focus on:

- Lake Valley, 2016 (from the beginning to about 4:05)

- Everything and More, 2015 (from about 9:30 to the end).

There is also an artist talk with Rachel Rose that you can access on the Nasher Sculpture Center’s YouTube channel. She discusses Lake Valley and shows additional still images, installation views, and video clips starting at 31:04.

Questions to Consider:

- Can you describe some of Rose’s influences? What feelings inspire her and how does she explore these?

- Consider how Everything and More addresses themes of mortality, detachment, and the body.

- What role does sound play in Rose’s work and in her formulation of her pieces?

- What everyday materials has the artist incorporated into her work? Do you recognize any of these materials in the excerpts of her creations shown throughout the video?

- How does Rose use the everyday as a way to access the sublime?

- Can you describe the intermedia qualities of Rose’s videos?

- How is an effect of displacement achieved in Everything and More?

- What way(s) does Rose consider gallery space and orientation of the viewer when installing her work?

- Is Rose successful in connecting her installation to the real space and the virtual space simultaneously?

- How would you describe Rose’s process and where do you see evidence of this process in her work?

Conclusion

This chapter introduced you to different artists who work with digital video, revealing the breadth and variety of the medium. How do you think digital technology transformed video art? Can you compare and contrast an analog example of early video art from with a digital example from this chapter?

Before moving onto the next chapter, review the Key Terms outlined in the beginning of this reading and think about how you would apply them to the work examined here. For example, which works stand out to you as being collaborative? Which works rely on fragmentation, are hyperkinetic, or demonstrate qualities of hypermedia?

Finally, how is digital video, like many forms of New Media discussed throughout this textbook, participatory? How does it demonstrate the power and primacy of the viewer in the digital space?

Key Takeaways

At the end of this chapter you will begin to:

- Explain the history of video art.

- Describe and compare significant innovations in digital video art and video installation.

- Recognize developments in digital video art and consider how this medium is connected to the broader history of visual culture.

- Explain how video art relates to the elements of New Media Art.

Optional: Lesson Extensions

Below are some lesson extension activities to encourage learners to engage more deeply with the material presented in this chapter.

Discussion Idea

In this chapter, you studied various approaches to video art and learned about the different reasons artists employ video as a mode of artistic expression. The reading, “Busting the Tube: A Brief History of Video Art,” referenced the unique qualities of video that artists use, such as looping, feedback, and instant replay.

For your discussion post, pick one artist from the weekly module whose work demonstrates one or more of the qualities of Video Art mentioned above (looping, feedback, and instant replay).

Be sure to include the following in your post:

- The name of the artist you selected and the title of the artwork you’ll be discussing. (Remember, titles of artworks should be italicized.)

- Include a still from the video (or a link to the video) in your post.

- Discuss how and where the artist has used looping, feedback, or instant replay in the work.

- Be sure you write a few sentences describing the effect of this technique (or techniques) on the viewer.

- Don’t forget to respond to one of your colleague’s posts and identify another observation about the subject matter, content, or formal qualities about the example they selected. Please describe something different than what the original poster observed.

Creative Interpretation Ideas

- Rachel Rose uses digital collage in her video Lake Valley. Try making a collage inspired by Rose, or another artist, in this chapter.

- Sound can be an important quality to video art. Think of Dara Birnbaum’s use of the Wonder Woman soundtrack to heighten the sense of urgency in her video Technology/Transformation/Wonder Woman, for example. Is there a video presented here that inspires you to create a soundtrack to complement it?

- Paul Pfeiffer and Dara Birnbaum use looping, erasure, and repetition in their videos. George Legrady and Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau explore user-generated outcomes in their digital videos. Try your hand at one of the techniques an artist in the chapter explores; you can experiment with either digital or analogue methods. For example, can you create a user-generated artwork by asking your friends to contribute something (words, objects, etc.) to the final piece?

- Many of the artists examined in this chapter create worlds for the viewer to explore. Write a short story or a poem inspired by a work that resonates with you.

Further Questions to Consider: Reading, “Busting the Tube: A Brief History of Video Art” (PDF via the Video Data Bank)

- What role did feminist theory play in the conscious-raising efforts of the 1960s? (pg. 1)

- Why was television a primary target for activists in the 1960s? (pg. 2)

- What theory did Marshall McLuhan propose regarding the interaction of humans and technologies? (pg. 2)

- How did Radical Software hope to decentralize communication systems? (pg. 2 and 3)

- What connection is made between the consumerism advanced by T.V. and the art gallery system? (pg. 3)

- Why did artists embrace video? Why did media-activists embrace video? (pg. 3)

- Why are early examples of video art often in “reel-time”? (pg. 4)

- What are some examples of how the limitations of the early video equipment led to experimentation? (pg. 4)

- Feedback and instant replay are two critical visual characteristics of video that are discussed. Where do you see these effects in the examples from the module (e.g., Fragment of a Crucifixion)? What impact do these methods have on the viewer? (pg. 5)

- What happens when the gallery system begins to embrace video art? (pg. 5 and 6)

- What are some difficulties in collecting and displaying video art? (pg. 6)

- How did the visual strategies of video art change in the 1980s? What factors led to these changes? (pg. 7)

- What alternative models of communication has video art achieved? Where do you see the legacy of video art today? (pg. 8)

Selected Bibliography

Boucher, Marie-Pier, and Patrick Harrop. “Interview with Rafael Lozano-Hemmer.” Inflexions 5: Milieu, Techniques, Aesthetics, March 2012, pp.149–60. http://www.inflexions.org/n5_lozanohemmerhtml.html. Accessed August 27, 2020.

Dougherty, Cecilia. “Stories From a Generation: Video Art at the Woman’s Building.” In From Site to Vision: The Woman’s Building in Contemporary Culture, eds. Sondra Hale and Terry Wolverton. eBook, 2007. https://www.vdb.org/sites/default/files/2007FromSiteToVision.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2020.

Graham, Beryl Graham. New Collecting: Exhibiting and Audiences After New Media Art. Abingdon: Routledge, 2014.

Grovier, Kelly. “Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Subtitled Public.” Tate Museum. May 2015. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/lozano-hemmer-subtitled-public-t12565. Accessed August 31, 2020.

Horsfield, Kate. “Busting the Tube: A Brief History of Video Art.” In Feedback: the video data bank catalog of video art and artist interviews, eds. Kate Horsfield and Lucas Hilderbrand. (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2006), 1-9. https://www.vdb.org/content/busting-tube-brief-history-video-art. Accessed January 22, 2019.

Lew, Christopher Y. “Room With a View.” Whitney Museum, 2015. https://whitneymedia.org/assets/generic_file/50/rachelrose.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2020.

Marchese, Francis T. “Conserving Digital Art for Deep Time.” Leonardo 44, no. 4 (August 2011): 302–8.

Meigh-Andrews, Chris. A History of Video Art. Bloomsbury Academic: London, 2014.

Mondloch, Kate. Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art. University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, 2010.

Noll, A. Michael. “Early Digital Computer Art at Bell Telephone Laboratories, Incorporated.” Leonardo 49, no. 1 (February 2016): 55–65.

Paul, Christiane. “Renderings of Digital Art.” Leonardo 35, no. 5 (December 2002): 471–84.