6 Early Film and Animation

Early Film and New Media Art

New Media Art provides new ways for artists and non-artists to communicate and engage with the changing world around them. We’ve discussed printmaking as art that embraced the principles of New Media as early as the 15th century. We’ve also seen the ways that photography made art more accessible to many people in the nineteenth century, while it also struggled to gain acceptance as an art form and inspired visual artists to experiment with the new technology. Photography was and is New Media Art because it allowed artists to invent new realities, to make multiple copies of an image and eventually empowered the broader population, changing their experiences with the world around them by allowing them to create their own images, preserving the past, freezing moments and developing new understandings of time along the way.

As new technologies were introduced and the world around them began to change dramatically modern artists, including photographers like Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) began to argue that art can invent new realities instead of trying to create an imitation of reality that is deeply indebted to the past, to antiquated technologies. In this chapter we’ll consider a major influence on New Media Art that allowed artists to explore the excitement, tensions and complexities of modern life in ways that would have been impossible using more traditional approaches to traditional art forms like painting. This chapter builds on our discussion of still photography, to discuss the development of photographs that move, one of the most important aesthetic strategies of New Media Art. In the following unit, we’ll dive into the history of early film and animation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Watch & Consider: The Invention of Cinema

Watch The Invention of Cinema (1888-1914) video embedded below. Creator: One Hundred Years of Cinema, Source: YouTube.com (2016) (5:40 minutes.)(Select CC for Closed Captions.)

Questions to Consider:

- How does early film fit into the history of New Media Art?

- Why can film be described as Time Based Art?

- How was early film responding to the changing technological world of the Machine Age in the early twentieth century?

- What are some major differences between film and painting? What are some similarities?

- How did early filmmakers use the visual elements and principles of design to convey ideas?

- In what ways did early film influence the visual arts?

Optional viewing:

“The History of the Movie Camera in Four Minutes: From the Lumière Brothers to Google Glass” by the Society for Camera Operators. (4 minutes) Openculture.com (2014)

Elements of New Media Art

While reading the rest of this chapter, consider how the Elements of New Media Art listed below relate to the works of film and animation discussed in this chapter.

- Expands the definition of art

- Exploits new technology for artistic purposes

- Merges new media with old media

- Time – unfolds over time, uses time as a design element

Experiments with Photography

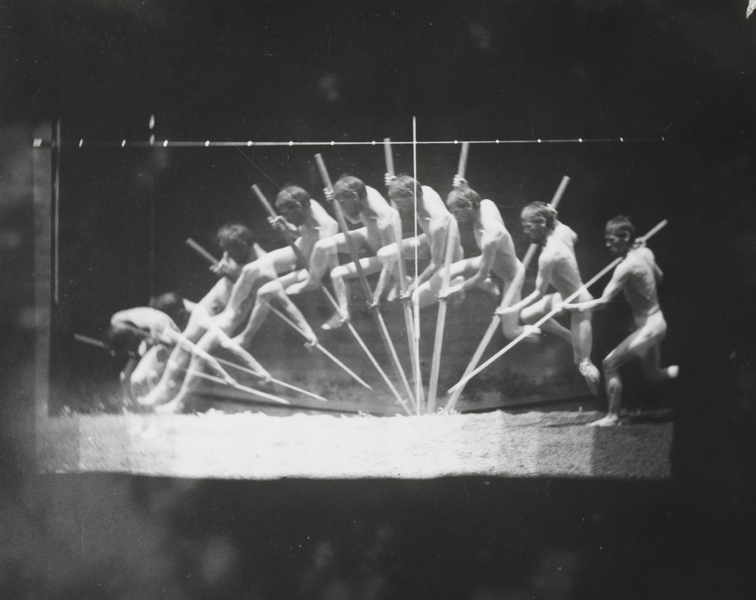

Long before the first motion pictures were shown to the public in the 1890s, artists were already using photography to explore time, manipulate perception and make static images move. Artists like the American painter Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) started using a camera to study sequential movement in the 1870s because he wanted to inform his painting with more knowledge about how the human body moves. He used a single camera and a perforated rotating disc behind the lens to capture a series of exposures on one negative. Eakins was inspired by a French scientist named Étienne Jules Marey (1830-1904), who was the first to record a series of movements on a single photographic surface.

Marey captured movement by attaching white stripes to people dressed in black in order to highlight the changes in their body positions as they performed certain actions. With his technique, called Chronophotography, Marey captured a series of exposures on one negative. He also made early short motion pictures, which were about 60 frames per second, placing him in the family of early influencers of modern film.

Marey: Motion Capture. Montage of Marey’s work by Sylvie-Jeanne Gander. Music by Gréco Casadesus. Creator: Gréco Casadesus, Source: YouTube.com (2013) (2:10 minutes)

Marey’s work and that of an American inventor and photographer named Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) both argue that photography is not just painting in another medium. They both saw that photography had the potential to do and show things that no other art medium could. Like Marey, Muybridge also tried to develop a method for capturing movement on a typically static photographic surface in the 19th century. But unlike Marey and Eakins, Muybridge used multiple cameras and created a sequence of photographs that when shown in rapid succession created the look of motion.

Listen & Consider: Capturing Time

Listen to this segment from the podcast Radiolab about Muybridge’s early experiments with motion. You’ll also hear about major changes experienced by Americans in the nineteenth century, including the way that railroads changed people’s understanding of time. While you’re listening, make a list of the major aspects of life that began to change in the nineteenth century and consider some of the ways that people’s understanding of time began to change as a result of new technology.

Start the podcast at 10:30. The section on Muybridge starts at 15:00. End at 19:48.

(9.18 minutes total) (You can listen to the entire podcast if you have the interest.)

- What are some of the ways that people’s understanding of time changed as a result of new technology in the nineteenth century?

- What are some significant aspects of life that changed as a result of new industrial technologies and this new understanding of time?

What it would look like if Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs of a race horse were shown in succession. Photographs from 1878. Creator of video: silentfilmhouse. Source: YouTube.

A Paradigm Shift

In the nineteenth century, people’s understanding of time became less local and more standardized. The idiosyncratic understanding of time in various regions and towns became more unified, more corporate. The new technologies that required this shift, of which the most significant example is the railroad, also resulted in people being able to communicate more over longer distances and in people being able to travel faster and farther than ever before. Imagine how dramatically people’s understanding of space, community and their world began to change as a result of these new technologies. We’ll continue to see the impact of technologies from the Industrial Revolution on early 20th century throughout this chapter, including the way that structured time and photographic technology allowed manufacturers to track and record the movement of workers, to further the goals of capitalism by increasing efficiency and productivity. The impact of this oppressive structured time on average workers is explored in an early film by Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977) titled Modern Times.

Early Motion Pictures

Muybridge and other early inventors were instrumental in allowing humans to see things they hadn’t previously been able to see prior to the invention of photography. Being able to see frozen moments, to see movement stopped and to see time captured, held forever, like water frozen in time, would have been an exciting and perhaps paradigm shifting experience for people looking at images in the nineteenth century.

Thanks to the invention of photography, people were trying to find new ways of sharing images with the public in exciting, innovative ways. Some inventors used photography to create Magic Lantern slide presentations.

But static Magic Lantern shows were only the first step. As early as 1834, people had access to a small device called a Zoetrope which allowed them to see images in motion. A zoetrope is a rotating cylinder with images on the inside. The viewer looks through holes cut in the side and gets a visual impression of a single image in continuous motion. In fact, while Muybridge did not originally create his iconic horse photographs to be seen in motion, the series was eventually published in Scientific American, with instructions on how to cut the images out and put them into a zoetrope.

Zoetrope with animation of Muybridge galloping horse images. Creator: Zoetrope Praxinoscope Animations. Source: YouTube. (2012) (1:15 minutes)

Fourty-three years after people had been using the zoetrope, in 1877, Charles-Emile Reynaud (1844-1918) designed a new device called a praxinoscope. The praxinoscope has less image distortion than the zoetrope because viewers look down on top of the device and not through holes on the side. But both of these early moving image viewing devices relied on a principle called the persistence of vision, which is the reality that the visual sensations we see, persist even after the image is no longer in front of our eyes. Our mind connects all of the images seen separately to create the visual effect of seamlessly flowing movement. This illusion of movement is the basis of modern analog film.

Praxinoscope with multiple animations. Music by Bill Frankeberger. Creator: Bill Frankeberger. Source: YouTube. (2017) (1:48 minutes)

In the earliest films, you can notice a visible “blink” between image frames because there are only a few frames per second. The more frames per second used, the fewer blinks happen between images. However, even with the blinks, it must have been mind blowing to walk into a dark room to view a short motion picture for the first time in the 1890s and to have an experience where it seemed like space and time as you knew it were annihilated. Now the very first films were not shown in dark rooms, but in Kinetoscope parlors. These rooms featured peep-hole machines designed by the American inventor Thomas Edison (1847-1931), were people crouched to look through a viewing lens and watch tiny moving photographs arranged in short loops.

Short video showing the insides of an early kinetoscope. Creator: thekinolibrary. Source: YouTube. (2013) (25 seconds)

The earliest motion pictures shown in Kinetoscope parlors were short clips like this one created by Thomas Edison, recording a man sneezing. By 1893, Edison’s kinetiscope was an international sensation.

Record of a man sneezing on Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope. (Original 1894) Creator: W.K.L. Dickson. Source: Library of Congress via YouTube. (22 seconds)

In 1895, the French brothers August Lumière (1862-1954) and Louis Lumière (1864-1948) advanced Edison’s technology and started showing longer series of moving images to the public in larger rooms. Their first paid public screen consisted of 10 short films, each about 50 seconds, and was held at the Grand Café on the Boulevard de Capuchines in Paris. Early films by the Lumières were shown in cafes, department stores and circuses, but by 1896, the brothers were opening Cinématographe theaters and showing their films in major cities across the world including New York, London, Cairo, Alexandria, and Brussels. By 1900, a cinema culture had developed in many parts of the world and cinema became a new social environment where classes and genders mixed often. It may be challenging for us today to imagine how surprising and awe-inspiring these early films were and this new social experience was for viewing audiences. There are reports of early viewers watching Arrival of a Train at a Station (L’Arrivée d’un Train en Gare de la Ciotat) and jumping out of the way, as the train approached the foreground of the screen, surprised by the illusion of motion displayed by this dramatic new technology.

Watch & Consider: Watching Early Films

Watch Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat, 1895, by August and Louis Lumière (The Lumière Brothers) embedded below. The music on this video is not original. Uploaded by raphaeldpm. Source: YouTube. (49 seconds)

Questions to Consider:

- Imagine you are looking at short films by Thomas Edison in a kinetoscope parlor and then watching the Lumière Brothers Arrival of a Train in a large, dark room full of people.

- What are some of the differences between the experience of looking at moving images in the personal kinetoscope vs. being in a room looking at the wall?

- Consider size of image, atmosphere in the room, sounds, smells, other factors that might impact your experience.

- What connections can you draw between the images people saw in kinetoscope parlors and gifs you use to communicate today? What are some differences between those two forms of moving images?

- What other connections can you draw between the way you access (and make?) moving images today and the way average people accessed moving images in the early 1900s?

Another iconic early film made by the Lumière Brothers was a film of the American dancer Loïe Fuller (1862-1928), who moved to Paris in 1893 and developed innovative choreography including a dance called the serpentine dance, which she performed with a costume of moving, billowing cloth. She employed stagehands to use different colored gels to project colors onto the fabric, creating a dynamic visual experience for the viewers. In order to recreate the impact of her performance and before the invention of color film, the Lumière’s hand painted film cells to suggest the multi-colored experience of watching Fuller perform in person.

Watch & Consider: Intermedia and Early Film

Watch Loïe Fuller filmed dancing the Danse Serpentine filmed in 1896 by the Lumière Brothers. Hand colored film stock. Source: UbuWeb. License: Public Domain. (42 seconds)

Questions to Consider:

- Watch this film and use it to explain how early film captured motion in ways that are different than still photography.

- In what ways do you think this film opened up new ways of seeing for young artists in the early 20th century?

- What are some ways that this film uses multiple art mediums (sound, film, dance, painting, set design)? You’ll learn the term intermedia later in this text, but this film is a good example of intermedia art.

Focus: Early Global Filmmakers

The new medium of film spread rapidly with artists and inventors all over the world adopting the new technology to their own needs and ideas. The first Latin American filmmaker, Manuel Trujillo Durán (1871-1933), got his start in film by organizing the first showing of films in Venezuela on an Edison Vitascope in 1897. Shortly after, he began to make and show his own films like Un celebre especialista sacando muelas en el gran hotel Europa (A Famous Puller of Teeth at the Grand Hotel Europa).

Shibata Tsunekichi (1850-1929), made his first films, also the first made by a Japanese filmmaker for the Lumière brothers in 1898. He then went on to make films for Japanese producers, including most famously, Momiji-gari (Maple Leaf Hunters) which was an historic account of Danjuro IX and Kikugoro V, two Kabuki theatre actors.

Shibata Tsunekichi, Momijigari (Maple Leaf Viewing) (1899) Music not original to the film. Print preserved at the National Film Center of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. Uploaded by Canal del Elvira. Source: YouTube. License: Public Domain. (2:24 minutes.)

Mexico’s first film, Don Juan Tenorio was created in 1898 by Salvador Toscano Barragan (1872-1947), who continued to make local Mexican film in the early 20th century and screen foreign films like Méliès’s Voyage to the Moon for audiences in Mexico City.

In Bombay, India, Harischchandra Sakharam Bhatvadekar (Save Dada) (1868-1958) decided to make films after viewing a screening of Lumière brothers cinema. He made his first film in 1899 by recording a wrestling match at the Hanging Gardens in Bombay. In the early 1900s, Tunisian filmmaker Albert Samama Chikly (1872-1934) made the first North African films, including the first fiction film, Zohra (1922) which stars his daughter, actress Haydée Samama Chikly.

Albert Samama-Chikly, Zohra. (1922) Print preserved at Les Archives du Film du Centre National de la Cinématographie. Uploaded by Silent movies. Source: YouTube. License: Public Domain. (9:11 minutes)

Finally, the court photographer of the Shah of Iran, Mirza Ebrahim Khan Akkas Bashi (1874-1915), was asked to purchase filmmaking equipment after the Shah visited the Paris World’s Fair in 1900 and toured the Lumière film exhibit there.

Focus: Film and the Machine Age

At the 1900 Paris World’s Fair, new media art, new technology, and movement all came together to shock and impress. This particular world’s fair even featured a moving sidewalk, so viewers moved and had a view of each exhibition space they passed, as if everything was in motion. In many ways, this is a powerful metaphor for the impact film had on early 20th century art. Film’s ability to capture motion and preserve time, opened up new ways of seeing for young, avant-garde artists.

Artists began to experiment with film, to see what it could do. The French artist Georges Méliès (1861-1938), one of the celebrated heroes of Martin Scorsese’s film Hugo, became the first filmmaker to use multiple cuts and repeated scenes to establish time moving forward, in his 1902 silent film, A Trip to the Moon (Le Voyage dans la Lune). This film, the first sci-fi adventures in film history, tells the story of six astronauts launched from a cannon to explore the moon. It also features one of the most unforgettable moments in film history, the man in the moon, being poked in the eye by a rocket ship.

Georges Méliès, Le voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon). 1902. Music by Erich Wolfgang Korngold & Laurence Rosenthal not original to the film. Uploaded by Ckdexterhaven. Source: YouTube. License: Public Domain. (10:28 minutes) (Start at 4:00 minutes for the iconic moonshot.)

The invention of motion pictures was probably one of the most significant developments of the early 20th century. But, just like photography, many in the early 1900s, felt that film was just a machine, just a scientific tool and couldn’t be considered fine art. However, as often happens when new technologies or approaches are introduced, it was freeing to be marginalized in the art world or not considered art at all. In the context of film, this marginalization allowed many artists to begin experimenting and manipulating this new time based art. Artists like the Spanish filmmaker Segundo de Chomón (1871-1929) began to experiment on films like Symphonie Bizarre (1909) with slowing the film down, making it run backwards and drawing directly on the film to create his desired effects.

Segundo de Chomón, Symphonie bizarre, 1909. Produced by Pathé Brothers. Music by Toscano Filho, José Menezes and Neusa Rodrigues. Edited and music added by Antônio Nóbrega. (2005) Source: Rádio Educativa Mensagem (REM) via YouTube. License: Public Domain. (3:06 minutes)

Watch & Consider: Méliès and Chomón

After watching George Méliès’ A Voyage to the Moon (1902) and Segundo de Chomón’s Symphonie Bizarre (1909) consider the following questions:

- Imagine yourself as a painter, watching this film for the first time in a dark room with other people in 1900 Paris.

- What are you thinking?

- How do you think these two films and the other moving pictures you’ve seen in this unit might impact your work as a painter?

Along with the many popular films of the early twentieth century, some avant-garde painters started to make their own abstract films, using moving images to explore time, technology and modernity. Some artists were quite excited about the possibilities of this new media and wanted to use film to show how space and time as it was known in the past had been transformed in the modern era thanks to industrialization and Machine Age technology. The turn of the century in Europe was dominated by major thinkers challenging traditions of Western thought, including the scientist Albert Einstein (1879-1955), who published his paper “Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies” in 1905, which outlined his theory of relativity, explaining that space and time are not absolute, but are relative to the observer. So Europeans were slowly introduced to the reality of living in a world of shifting perspectives, where the appearance of an object is in a constant state of flux depending on the point of view from which it is seen. The Spanish painter Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), was among many painters who were awed while watching films by the Lumière Brothers on a large screen, 15 by 27 meters high at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair. He’d actually seen his first film four years earlier on a smaller screen. And the Cubist painting style that he later developed was greatly influenced by the time based arts of film and dance that he was exposed to in the early 20th century.

The Cubist painter and designer Fernand Léger (1881-1955) made his own film in 1924 called The Mechanical Ballet (La Ballet Mécanique). As a work of proto-New Media Art, this film is significant because it was the first film collage, with no narrative and no linear structure. Léger employed one technique that many modern artists used to expose the chaos of the Machine Age, simultaneity. He did this by showing multiple viewpoints and multiple moments in time in the Mechanical Ballet, along with rejecting linear plots and timelines, playing with the viewers perception of time and space. In this film, Léger juxtaposes the dynamic motion of kitchen utensils, machine gears, rotating disks and dancing bottles with human body parts, giving the mechanical universe a human face in moments throughout the film, both demonstrating and maybe challenging the dehumanization of the machine age. Léger was impacted by his experiences with new technology as a soldier during World War I, and the year he spent in the hospital after being gassed on the front lines in 1917. His ambivalence about the wonders of the Machine Age permeates this experimental film.

Watch & Consider: Mechanical Ballet

Watch this excerpt of Ballet mécanique, 1924 by Fernand Léger. 35mm film (black and white, silent), full film is 12 min. Music by George Antheil added later. Original source for this video clip “The Original Ballet Mechanique – George Antheil’s Carnegie Hall” Uploaded by Andy-80. Source: YouTube. (8:30 minutes)

Questions to Consider:

- Identify one machine part or mechanical device you recognize in the film.

- Describe that part of the film.

- How has Leger presented that machine part?

- Use some adjectives to describe it.

- Choose one place in the film with part of a human body (lips, legs, hands, torso, etc.). Describe it.

- How is the part you’ve just described different from or similar to segments of the film that present mechanical devices or machines?

- Identify some moments of fragmentation in this film. What effect do they have on you as a viewer? How do they add to the mood of the film?

- Identify moments of repetition in this film. (Keep in mind you are only viewing a clip.) What effect do they have on you?

- What do you think Leger is saying about new technology and life during the Machine Age given the aesthetic choices he has made?

In the past, life had been more static, but science and technology forced modern humans to experience time, space and motion much more dynamically. Reality was in a constant state of flux and that complexity is explored in Léger’s film. Uncertainty and ambiguity became a way of life in the early 20thcentury and Léger’s film highlights this new modern reality through the manipulation of the relatively new medium of film. Human perception was constantly being altered by the pace of modernity and early experimental films like Léger’s attempted to respond to this new reality. The old world was gone and artists were beginning to search for ways to explore and express the new, strange and terrifying world they were surrounded by. They wanted to use the new technology of new media to open people’s eyes and ears to the beauties and horrors of the modern machine age. Some modern artists turned to film because they wanted to engage viewers in ways that traditional art of the past did not. Film engages the viewer in meaningful ways because the total film doesn’t in fact exist anywhere other than in the viewer’s mind.

Along with Léger, other visual artists who were trained as painters and photographers, began to make experimental film in the 1920s, including Hans Richter (1888-1976), who made the very first purely abstract film in 1921, titled Rhythmus 21.

Hans Richter, Rhythmus 21, 1921/23, black and white silent film. Music not original. Uploaded by pablojmurphy. Source: YouTube. License: Public Domain. (3:08 minutes)

Photographer Man Ray (1890-1976) also began making poetry with film by splicing, editing and manipulating the film stock to create abstract compositions in films like Emak Bakia (Leave me Alone) from 1926.

Man Ray, Emak-Bakia (Leave me Alone), 1926, black and white film, 16 min. Music by Anthony Paul Mercer not original. Uploaded by lapetitemelancolie. Source: YouTube. License: Public Domain. (16:08 minutes)

Artists associated with the Surrealist movement, found film a particularly rich new medium, for attempting to access The Unconscious, through non-linear time frames and bizarre juxtapositions achieved through film editing, as seen in iconic Surrealist films like Un Chien Andalou (The Andalusian Dog) (1929) by Luis Buñuel (1900-1983) and Salvador Dalí (1904-1989).

https://youtu.be/IfyzOxaMKts

Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí. Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog). 1929. Black and white film. Original score by Richard Wagner from Tristan and Isolde. Uploaded by Storia del Cinema. Source: YouTube. (15:49 minutes) (The film was originally shown with French intertitles. For English translations of the intertitles see this version of the film. Note that this version has had a new score added by Mordant Music.)

Some of these visual artists felt that film could do things that painting couldn’t, while others saw a clear relationship between traditional art forms like painting and the new media of film. This relationships is explained by painter Hans Richter in the following way:

“I conceive of the film as a modern art form particularly interesting to the sense of sight. Painting has its own peculiar problems and specific sensations, and so has film. But there are also problems in which the dividing line is obliterated, or where the two infringe upon each other. More especially, the cinema can fulfill certain promises made by the ancient arts, in the realization of which painting and film become close neighbors and work together.”

Watch & Consider: Early Experimental Film

Choose one of the avant-garde films embedded above to watch. Consider the questions below while viewing.

- What do you think Richter meant by the statement quoted above?

- What relationship does he draw between painting and film?

- What are some similarities you can draw between the film you watched and painting? (If you are familiar with modern painting from the early 20th century, you can specifically reference that, but if not, connect the film to other aspects of painting you’re familiar with.)

- What are some ways that these experimental films are pushing the medium of film beyond its original function?

Focus: The Birth and Rebirths of a Nation

While some artists took experimental approaches to film that did not involve linear narratives, other pioneering filmmakers purposefully wove linear narratives and used the medium of film in effective ways, to engage in a dialogue about American history. D.W. Griffith’s (1875-1948) The Birth of a Nation (1915) is considered a landmark film because it was the first 12-reel, 3-hour long film ever made and because the innovative camera work heralded a new approach to telling stories using moving pictures. It was also the first blockbuster film and the first film ever screened at the White House. This is significant because the film was originally titled The Clansman and as that title demonstrates, it is a deeply racist film. So the history of new media is infused with and engaged to the history of racism in America. In 2015, contemporary artist DJ Spooky, aka Paul D. Miller (born 1970), reimagined the film from the perspective of DJ culture, creating Rebirth of a Nation, described by Spooky as a “DJ booth applied to cinema”.

Elements of New Media Art

While reading about the project by DJ Spooky discussed in this section, consider how it engages with these two Elements of New Media Art.

- Remixing – using images or things made by others in new ways

- Challenges the status quo

In this remixing of a racist icon of film history, Spooky manipulates moments from the 1915 film, juxtaposing them with historical footage, and new sounds from the 21st century, to expose the way that this film demonized Black Americans and shaped race relations throughout the modern era. DJ Spooky’s remixing of original art made by someone else, is an integral component of New Media Art, which is philosophically related to Hip Hop strategies of appropriation and remixing. Spooky’s work is also engaged with New Media Art concepts through the critical look at a work of film from the American past. New Media Art often engages with and deconstructs dominant narratives and that is precisely what DJ Spooky does in his Rebirth.

Trailer for Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky’s Rebirth of a Nation. 2007. (1 hour 40 minutes) Uploaded by International Film Festival Rotterdam. Source: YouTube. (2:34 minutes) The full film can be found in your local library or purchased through multiple sources. See DJ Spooky’s website for more details.

Spooky’s critical approach is related to a much earlier responses to D.W. Griffith’s film, pioneered by Lincoln Motion Picture Company, which formed in 1916 to produce films for a Black audience. They produced five films by 1920, including Within Our Gates (1920) by Black director Oscar Micheaux (1884-1951), staring celebrated actress Evelyn Preer (1896-1932). (You can find the full film Within Our Gates streaming on YouTube from various uploaders.) Micheaux wanted to provide a different perspective on what it meant to be Black in America in the early 20th century. Micheaux argued that he created the film in response to the social instability present in America after World War I, but many continue to see it as a critical response to Griffith’s film. All of Micheaux’s films including Within Our Gates, focus on contemporary Black life in America and attempt to counteract the negative, racist stereotypes drawn from the history of minstrel shows, that continued to prevail in American culture after the Civil War and are supported in films like Birth of a Nation. Another significant film made by Lincoln is By Right of Birth (1921) directed by Clarence Brooks (1896-1969).

Clarence Brooks, By Right of Birth, 1921. Black and White film. Lincoln Motion Picture Company. Uploaded by Department of Afro-American Research Arts Culture. Source: YouTube. License: Fair Use. (See also YouTube video description for more information about Fair Use.) (4:10 minutes)

Watch & Consider: Rebirth of a Nation

Watch the trailer for DJ Spooky’s Rebirth of a Nation embedded above and if possible to find, watch the entire film.

DJ Spooky’s Rebirth of a Nation at Chicago’s Millennium Park (6/20/16)(Full video 1 hour 31 minutes)

Read “Why Remix Birth of a Nation?” by Kriston Capps. The Atlantic (2017).

- How does DJ Spooky have a dialogue with D.W. Griffith’s iconic film?

- DJ Spooky is using a New Media strategy of remixing (or appropriation) here, by borrowing parts of Griffith’s film and recontextualizing the entire work. In what way does Spooky challenge the racist narrative laid out in Griffith’s film?

About this project DJ Spooky has said:

“In a certain sense what I’m doing is portraying the film as he intended it,” DJ Spooky says of his remix. “This is a film glorifying a horrible situation. And I think a modern sensibility is something where people will look at this and go like ‘Oh, I can’t believe this, I don’t relate to it, I don’t think this is right, what does he mean?’ So it’s not letting him off the hook so much as presenting the film and actually having it fall in on itself.”

3. What do you think DJ Spooky means? After watching parts of Spooky’s work (or the entire piece) do you think he effectively makes Birth of a Nation “fall in on itself”? If so, explain using one example from Spooky’s remix.

Focus: Early Animation

We’ve been discussing the history of moving images as early New Media Art and another significant part of that history is the history of animation. Animation is also Time Based Art and is also related to more traditional art media like drawing and painting in interesting ways.

Note: A stand alone chapter on Animation is in the works! In the meantime, watch these two great introductory videos from PBS.

Watch Frame by Frame: The Art of Animation and Motion Graphics from Off Book PBS Digital Studios. 2012. Source: YouTube. (6:45 minutes)

Watch Frame by Frame: The Art of Stop Motion Animation. PBS Digital Studios. 2013. Source: YouTube. (8:07 minutes)

Watch & Consider: Early Animation

Watch the following examples of early animation:

Émile Cohl, Fantasmagorie, 1908, hand drawn animation. Uploaded by silentfilmhouse. Source: YouTube. (1:16 minutes)

Winsor McCay, Gertie the Dinosaur, hand drawn animation, 1914. Uploaded by Open Culture. Source: YouTube. (13:51 minutes)

BBC Ideas. Lotte Reiniger: The Genius Before Disney. Short Documentary about the animation artist, Lotte Reiniger. 2018. Source: YouTube. (2:15 mutes)

Questions to Consider:

- In what ways does this early animation relate to the zoetrope and other devices that relied on persistence of vision?

- Some of the animations you watched involve cycling, which is repeating an animation or reusing a sequence multiple times in a film. Identify one film where you see cycling and explain how cycling is used.

- Do you think the animation you watched is a good example of narrative animation (animation designed with a storyboard) or non-narrative animation (designed without a storyboard, perhaps even non-linear)?

- What makes animation a good example of Time-Based Art? How does animation use time as a design element?

- What are some of the differences between the hand drawn animation of Émile Cohl (1857-1938) and Winsor McKay (1869-1934) and the silhouette animation of Lotte Reiniger (1899-1981)?

Key Takeaways

At the end of this chapter you will begin to:

-

- Explain the history of early film.

- Describe and compare significant innovations in early film technology.

- Recognize developments in the field of motion pictures and consider how early film is connected to the broader history of visual culture.

- Explain how early film relates to the elements of New Media Art.

Selected Bibliography

Bordwell, David and Kristin Thompson. Film History: An Introduction. New York: McGraw-Hill Company Inc., 2003.

Bendazzi, Giannalberto. Cartoons: One Hundred Years of Cinema Animation. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. 1994.

Dirks, Tim. “The History of Film: The Pre-1920s, Early Cinematic Origins and the Infancy of Film.” Parts 1 and 2. AMC Filmsite.

Elder, R. Bruce. Harmony and Dissent: Film and Avant-garde Art Movements in the Early Twentieth Century. Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2008.

Glimcher, Arnie, director. Picasso and Braque go to the movies (2008).

Herbert, Stephen and Luke McKernan. Editors. Who’s Who of Victoria Cinema. Web.

Horrocks, Roger. “Experimental film.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed 8/13/19.

Lumet, Sidney. Making Movies. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.