13 The Digital Revolution

New Media Art in the Digital Age

In this unit, we’ll discuss how concepts of New Media Art relate to the Digital Age. We’ve seen some New Media artists argue that the best way to revitalize culture is to creatively integrate art into everyday life and make viewers producers instead of passive observers. So in the era of Web 2.0, a term coined by Tim O’Reilly in 2004, New Media approaches became more prevalent because, while Web 1.0 limited people to viewing content passively, a Web 2.0 site or app allows users to interact and collaborate with each other, creating user-generated content on social media sites, blogs, wikis or video sharing sites. This means that some of the concepts of New Media became even more relevant in the early 21st century.

Artists have only been using digital technologies for a few decades, but as we’ve seen, new technologies and New Media Art concepts are part of a much longer history of image making. So while concepts of art have been radically transformed by New Media, this transformation did not begin with the introduction of computers in the 1980s or the Internet in the 1990s. The transformation has been happening in the art world for at least a century. New Media Art did not arise in a vacuum. In fact, one definition of New Media Art is art that exploits the emerging technology for artistic purposes. So we can find the roots of New Media Art in projects that make use of emerging media technologies and projects that are concerned with the cultural, political and aesthetic possibilities of new tools going all the way back to the 19th and 20th centuries.

In fact, the history of modern computing and digital technology began in the Early Modern Era with Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz (1646-1716), who invented a calculating machine that used the binary system in the 17th century. Ada Lovelace (1815-1852), a 19th century mathematician, became the first to recognize the full potential of computers beyond just calculation. She also developed the world’s first computer language, one-hundred years before digital computers. If you’re interested in learning more about Ada Lovelace, check out this fictional account of her life by the New Media Artist Lynn Hershman Leeson (born 1941), Conceiving Ada (1997). (This link takes you to a trailer for the 82 minute film. You should be able to find the film in your local library.)

The History of Computers

After the early explorations of pioneers like Lovelace, the essential ideas of modern computing were articulated in the 1940s and 50s, including networking, using computers for real-time control and graphical interface display. In the 1960s, the most significant development in computing was the Internet, though we can also find strong conceptual connections between computing and avant-garde art of the 1960s.

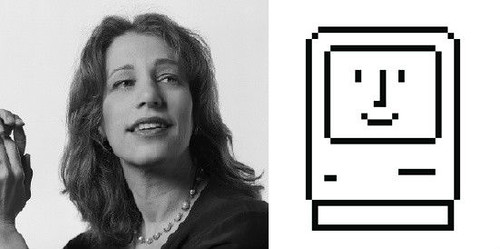

When the Macintosh computer was released in 1984, artists and designers were among the first to realize the potential for this new technology. Macintosh popularized the graphical user interface, designed by Susan Kare for Apple. It also had a simple drawing and painting program the emphasized a new role for the computer as a creative tool. You can read a critical analysis of earlier developments in graphic user interface (GUI) during the 1970s in this essay titled “Black Gooey Universe” by American Artist (born 1989) in unbag (Winter 2018). American Artist explains the dominance of white, cisgender designers and proposes how that early dominance shaped racial biases and erasures online today.

By the end of the 1980s, when Adobe released their new digital image editing software called Photoshop, the position of the digital computer as an artistic tool, for creation, appropriation, manipulation and deconstruction, was solidified. While cultural theorists like Marshall McLuhan (1911-1980) were analyzing the media decades before the 1980s, other theorists added their voices to the dialogue and began to examine critically examine the roles for New Media as it started to leave the military, government, big business and academia. Both Jean Francois Lyotard’s The Post Modern Condition (1979) and Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation (1981) contain detailed discussions of computing and Sherry Turkle and Donna Haraway quickly arose as American academics engaging critically with this new technology.

The History of New Media Art in the US

But it wasn’t until 1995, that American universities and art schools, especially on the West Coast, initiated programs in New Media Art and Design and began to open faculty positions in New Media Art. One of the first websites devoted to online art called Net Art, was a site called ädaweb, developed by the Walker Art Center and named for Ada Lovelace. (adaweb.walkerart.org) It was developed in December of 1994, the same month that Netscape released its Internet browser and just one year after the first web browser Mosaic was introduced. Äda Web was curated by Benjamin Weil with the goal of both mounting online exhibitions and commissioning online art projects. Over the course of its life, ädaweb presented more than two dozen projects all meant to encourage interaction on the World Wide Web. The organizers explained that they saw their site as “A research and development platform, a digital foundry, and a journey. Here artists are invited to experiment with and reflect upon the web as a medium.” (From the Äda Web manifesto)

artnetweb was another collaborative founded in 1993 to provide artists access to the investigate and use new technologies in their projects. In 1997, they organized PORT as an “exhibition of networked digital worlds on the Internet, providing a platform for experimental, networked and time-based art projects. Another venue for Internet Art between 1997 and 2003 was Gallery 9, also organized by the Walker Art Center. You can find an archive of the work they supported linked here Gallery 9.

The Dia Foundation also began commissioning artists to make work for the Web in 1995. Dia selected artists based on their interest in exploring the aesthetic and conceptual potentials of the medium. They were not concerned with choosing artists who had a fluency or proficiency in digital tools or computer programming. Then, for the first time in 2000, the Whitney Biennial in New York had a room dedicated to Net Art and in 2001 there were two large survey exhibitions of Net Art and other forms of New Media Art, Bitstreams at the Whitney and 010101: Art in Technological Times at SFMoMA. So what had been a cultural underground, making art to critically engage with the Internet and the Web, was becoming an established academic and artistic field by the early 2000s.

Between 2001 – 2003, New Media Artists Mendi and Keith Obadike (both born 1973) organized Black.Net.Art Actions, which is a suite of artworks that argue that racial discourses aren’t just relevant online, they are essential to how we interact with computer networks. Historian Megan Driscoll has written about their work and about race and identity in the early developments of New Media Art online, explaining that in the 1990s and early 2000s, there was a prevlanet myth that race disappears online. And that myth shaped how people understood the emancipatory potential of computer networks. Driscoll argues that the actions taken by Mendi and Keith Obadike helped counter that myth by revealing how online encounter are permeated by the histories that influence one’s ideas and experiences of race, demonstrating that the relationship between race and computer networks is an essential subject for internet-based art. You can read the entire exploration of Black.Net.Art.Actions here, Dr. Megan Driscoll, “Art, Race, and the Internet: Mendi + Keith Obadike’s Black.Net.Art Actions,” in Smarthistory, September 21, 2020.

Listen & Reflect: An Oral History of the Internet

Watch An Oral History of the Internet #6: Mendi & Keith Obadike, Creator: NYU Abu Dhabi Art Gallery, Source: YouTube.com (2021) (44:37 minutes).

https://youtu.be/9nLMh5psgZE

Questions to Consider:

- What do Mendi and Keith Obadike have to say about what it felt like when the Internet started?

- What do they say about what it means to work, act and create art online?

- They talk about making art on the Internet as making public art. What do you think that means?

- What do they have to say about the Internet as a “utopian” and “democratic” space in the 90s?

- What can we learn about the early days of the Internet (and even the tech as it works for us today) by listening to New Media Artists like Mendi and Keith Obadike?

- Later in this chapter, you’ll look at work by an artist named Tabita Rezaire, who works to critique digital colonialism, what do the Obadike’s have to say about the legacy of colonialism in the early days of the Internet?

Explore & Consider: net.art

Examine the following net.art projects and consider how they engage you as a viewer:

- Jenny Holzer, Please Change Beliefs, May 1995, the first ädaweb project.

In this project, US artist Jenny Holzer (born 1950) explored the collaborative nature of the web by encouraging users to change her Truisms, a conceptual art project she had been working on since 1978.

2. Mendi Lewis Obadike, Keeping Up Appearances, 2001, Black Net.Art Actions project.

This is a hypertext project by Obadike, in which she recounts her experiences as a young Black woman with an older white, male mentor. Be sure to read each text and hover your mouse to uncover more aspects to the story.

3. Komar and Melamid, The Most Wanted Paintings, 1995

In this project, Russian artists Vitaly Komar (born 1943) and Alex Melamid (born 1945), attempts to discover what a true “people’s” art would look like. Through a professional marketing firm, they conducted a survey to determine what Americans prefer in a painting; the results were used to create the painting America’s Most Wanted. Look through as many examples of the paintings selected as you can

4. Francis Alÿs, The Thief, 1999

For his first project for the web, Belgian born, Mexican based artist Francis Alÿs (born 1959) created an animation, available as a screensaver, as his response to the computer, the network, and the ubiquitous Windows metaphor. The process by which he came to this clip has been documented in a series of short arguments where Alys investigates the parallels between contemporary interface design and “Alberti’s Window,” a method of linear perspective drawing encoded and canonized during the early Renaissance through Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472).

5. Wilfredo Preito, A Moment of Silence, 2007

For his first web-based project, Cuban artist Wilfredo Prieto (born 1978) invites visitors to participate in a moment of silence. When opening this project, take a deep breath. Your computer is not crashing.

Questions to Consider: net.art

-

How did you navigate each project you examined? Was it easy or difficult to find your way around in the work of art? Did you scroll, click around or use some other type of navigation?

-

What was the project like when you first entered? What did you expect and what happened when you started interacting with it?

-

What kind of interaction did the project allow? Describe the level of audience involvement. Could you change the work of art? Were you unable to change the project? What about other people who participate in the project, have they changed or add to it? Why do you think each artist chose the approach to audience involvement that they did?

-

What is each of the net.art projects you examined about? What themes are explored? What was the goal of each project?

-

How was your experience with net.art projects you examined different than visiting a gallery or a museum?

-

Did any of the web-based art projects you just examined reference earlier print-based technologies? If so, explain how.

Hypertext and Non-Linearity

As we’ve discussed, we can go back further and find correlations between new media throughout history and developments in new media today. For example, interactive computer art further develops ideas already explored in the art of the 1960s, continuing the shift from passive audience reception to active participation pioneered by Fluxus. There are also correlations between the reception of new technologies on the part of makers and the general public. There is often fear when new media is introduced as we’ve seen when printmaking was introduced to Europe and some were afraid that they would lose their livelihoods and others afraid that they would lose their positions of power within the dominant structure. Sometimes as a way of easing into a new paradigm, the first experiments with new media reference old media technologies. For example, in fifteenth century Europe, Johannes Gutenberg (died 1468) made his first printed manuscript look like it had been handwritten by a scribe. And as we have seen, some of the earliest photographs looked like paintings. Today, print culture is mixing with digital culture and the language and formats of print culture are still with us. E-readers and websites often employ the linear reading style of scrolling or turning pages despite the fact that hypertext, which allows for a non-linear engagement with multiple texts, was invented in the 1990s.

The linear reading methods employed by many digital tools were designed by people who learned to read using analog media like books. Hypertext, in contrast, allows a programmer to link information from other sources to their pages, creating a non-linear web sometimes called a rhizome. Along with having the potential to transform and complicate linear thought, new digital tools also challenge the logic of traditional art. Traditional art history and the art world assumes a one of a kind art object, made by a single, artistic genius and distributed through a set of exclusive galleries, museums or auction houses. But as we’ve seen, New Media Art privileges the existence of numerous copies and many different states of the same work. The user is often able to change New Media Art through interactivity. Authorship can be collaborative. And distribution of New Media Art can bypass the traditional gallery system. For further context see the discussion of Hypermedia in the chapter on Digital Video Art.

Explore & Consider: Hypertext

Examine the hypertext projects linked below. Choose one and answer the questions listed below in relation to the web art project you have chosen.

1. Tim Rollins and K.O.S., Prometheus Bound, 1997

Tim Rollins (1955-2017) and K.O.S. (Kids of Survival), created a series of “dialogues” which weave together excerpts from Aeschylus’ play, studio discussions, and outside commentary. The outcome is pages or “scrolls” which are works of art that, as with all of their work, has been produced collectively.

2. Fantastic Prayers, begun in 1995, as a collaboration between writer Constance DeJong (born 1950), artist Tony Oursler (born 1957), and musician/composer Stephen Vitiello (born 1964). It challenges linearity through its presentation of text/poetry and prose, sound, video, images.

3. Also examine Wikipedia, not a New Media Art project, but as you probably know, Wikipedia is a free, collaborative, crowd-sourced encyclopedia, founded in 2001 and it’s a great example of hypertext.

Questions to Consider: Hypertext

- What are some of the differences between reading these texts and reading a physical book?

- What are some differences between reading these texts and scrolling through a news article or blog post online without hypertext?

- What makes a hypertext project non-linear? What are some advantages to reading a hypertext project? What are some disadvantages or downsides?

- Based on the definitions of New Media Art we’ve been developing, why would you consider hypertext related to New Media Art?

Relationships between New Media and Old Media

Scholar Lev Manovich, a professor of Digital Humanities, has suggested that digital computing and new media are a massive speed-up of manual technologies that already existed before computing. One example Manovich provides is linear perspective, which was used by human draftsman to create an illusion of 3-dimensional space on a flat surface, long before digital drawing, CGI and other digital animation tools were designed. Manovich also argues that Quick-Time, which was introduced by Apple in 1991, is a speed up of the Kinetoscope of the 1890s. Both tools were used to present short image loops. Both featured images approximately 2-3 inches in size. And both called for private viewing rather than exhibition in a large room full of people.

The invention of digital photography in the 1950s massively sped up image capturing abilities. Photoshopping is also a speed up of composite photography or collages made by people in the Victorian era and the early 20th century, by gluing multiple photographs together and sometimes rephotographing them. Contemporary means of digital image production and socially networked means of image distribution like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, TicTok, Flickr and Twitter, give global populations the possibility of presenting their photos, videos, and texts in ways they never could in the 19th or 20th centuries. Since the introduction of first Kodak camera “users” have had tools to create their own media, but it’s only recently that we’ve had access to multiple paths that allow media objects to easily travel and allow users to interact and collaborate with each other.

Digital Art also has parallels to Video art because video art was made possible by the introduction of the Sony Porta-Pak, which was cheap and easy to use allowing artists and other users to access the world of video for the first time. A generation later the introduction of the web browser led to the birth of computer art as a movement. New Media artists saw the Internet as an accessible artistic tool and they started using computers and eventually the Internet to explore the changing relationship between technology and culture. You can read more about the early years of video art in the Video Art chapter of this book. You can also read more about Digital Art that employs video in the Digital Video Art and Video Installation chapter.

Focus: Hacking Culture

As we become more and more engaged with the Internet in every aspect of our lives powerful questions have arisen regarding the ownership of digital media and information. The relationship between corporations, governments, and individuals online and the powerful influence of popular culture are issues being critically explored by contemporary New Media artists, including members of the Free Art & Technology (F.A.T.) Lab, Evan Roth(born 1978), Greg Leuch and Aram Bartholl (born 1972), among many others. Artists like Alexei Shulgin (born 1963) produced some of the earliest real-time performance art via the Internet, inspired by early 20th century Dada performance art. Also in 2000, in a critical exploration of the new Internet marketplace, eBay, a student named Michael Daines offered to sell his body under the sculpture category on eBay. Daines project recalls the work of early performance artists like Chris Burden and Marina Abramović who treated their bodies as sculptural objects. The project also hacks eBay and encourages user to think critically about the nature of buying and selling art and more specifically doing that online. These are similar to questions raised by Mendi + Keith Obadike in projects like Blackness for Sale also a project engaging with ebay and critically recalling the history of slavery.

New Media artist Mark Tribe (born 1966) has argued that remixing and culture jamming is a form of New Media Art also innovated by early 20th century Dada. In A Hacker Manifesto, written by McKenzie Wark in 2004, Wark extends the idea of hacking beyond to the computer and into other domains. Hacking is innovation, wherever it is practiced. By hacking codes, for example the codes of art, we create the possibility of new ways of thinking and new things to examine.

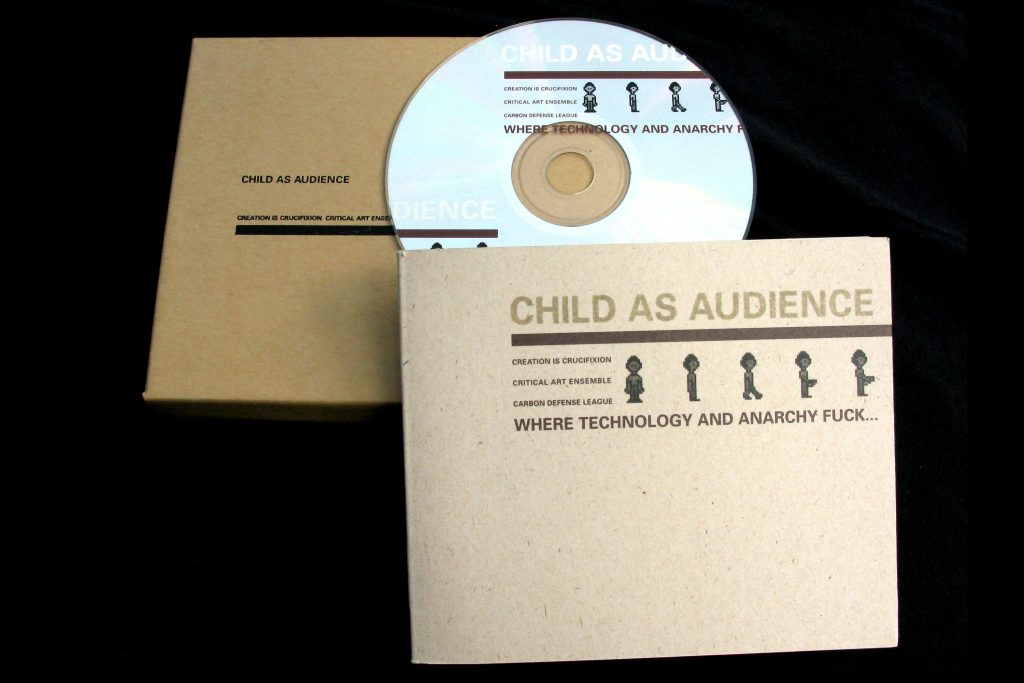

An excellent example of hacking and the influence of Dada culture jamming and is a project from 2001 by Critical Art Ensemble. The project, titled Child as Audience, was a CD-ROM with instructions on how to hack and alter GameBoy video games. So not only did this project involve taking a found object and found code and creating something new, but it also gave the power over to the viewers or users, allowing them to hack the game device in whatever ways they saw fit.

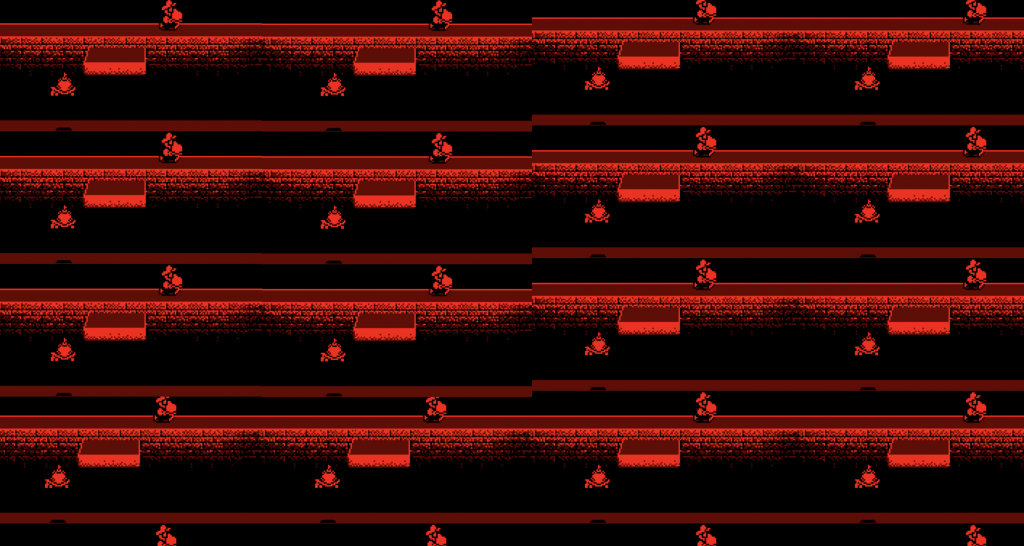

Another project called Prepared PlayStations, by the Radical Software Group, exploited bugs and glitches in PlayStation games to create game loops that were exhibited in art galleries in the context of New Media Art shows.

Radical Software Group, Prepared PlayStation RSG-THPS-4-2. 2004. Creator: Radical Software Group. Source: YouTube. (2:25 minutes)

Cory Arcangel (born 1978) is another artist who works across media and critically examines technology. He often hacks machines to make interventions that encourage users to think about the structure, aesthetic and interface of the technology in new ways. For example, he hacked a Super Nintendo cartridge to create his piece Super Mario Clouds, by removing all other components of the game Super Mario Brothers, until clouds are the only thing left.

Cory Arcangel, Super Mario Clouds, 2002. Uploaded by coryarcangel. Source: YouTube. (5:54 minutes.)

While these are more recent projects, game modifications have been happening as early as the 1980s, with skilled fans creating new items, weapons, characters and sometimes entirely new story lines for their favorite games. In fact, these modifications of digital games are indebted to the original interactive games born in the 1970s, Table Top Role Playing Games like Dungeons and Dragons.

Watch & Consider: Video Games at MoMA

Watch the TED talk buy Paola Antonelli titled “Why I brought Pac-Man to MoMA”, TED (2013) Source: YouTube (18:22 minutes).

Watch & Consider: The Case for Video Games

Watch “The Case for Video Games” by The Art Assignment from PBS Digital Studios (2020) Source: YouTube (13:27 minutes).

Questions to Consider: Video Games

- What are some of the reasons that Video Games can be considered New Media Art?

- What are some of the differences between traditional video games and hacking projects by artists like the Critical Art Ensemble, the Radical Software Group and Corey Archangel?

- Consider how the viewer or user is engaged with in some of the video games presented in “The Case for Video Games”, what are some of the different types of interaction that someone playing a video game might encounter? (Consider a traditional scrolling or platform games like early Mario, consider first person shooters, consider structured narrative RPGs, also consider sandbox or open world RPGs and MMORPGs (or Massive Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games) and simulation games like the Sims or Second Life.)

- What kind of user engagement does creative hacking involve and how is that level of engagement different than playing some of the different types of games you’ve described in response to the previous question?

- At the beginning of this book we talked about the artist Cao Fei (born 1978), who constructed a fictional, open world city in Second Life called RMB City (2008-2011). What are some of the differences between this project by Cao Fei and some of the video game formats you have described above?

Focus: Glitch Art

Another approach to digital art that can involve Dada Hacking and Readymade strategies is Glitch Art. Glitch Art is often made with lost bits of the old and new technology. Some Glitch artists manipulate old digitized photographs or old Internet gifs, using editing software to “corrupt” the image, creating layers or distorting pixel blocks to achieve a glitchy or distorted look. A “glitch” is something created as the result of a technology malfunction and in the 1990s, visual artists became interested in using digital glitches to make art. However, there are earlier precursors to Glitch Art, including works like Nam June Paik’s TV Magnet (1965) and Digital TV Dinner (1978) by Jamie Fenton and Raul Zaritzky.

Some of the earliest examples of Glitch Art made online was made by Jodi.org. A group formed in 1993 by Joan Heemskerk (born 1968) and Dirk Paesmans (born 1965). Jodi.org is a website that deconstructs the visual language of the web in the 1990s, by manipulating found HTML scripts and images. Like other examples of New Media Art we’ve looked at, Jodi.org exploits an emerging technology for aesthetic purposes. It is also an open system with no point of closure and temporal, rather than a fixed object.

More recently, the curator and scholar Legacy Russell has articulated the idea of Glitch Feminism as a tool to subvert dominant narratives and create alternate, radical futures. Russell identifies the glitch as a disruption, an embrace of malfunction, and a “tear in the fabric of the digital”. She notes that the digital has often been equated with the radical. But she argues that the dominant institutions currently defining the future of visual culture (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok and others) are anything but radical. One way she identifies a glitch is as a strategic occupation of these platforms that define our Internet status quo and privilege certain voices and certain identities over others. Russell posits a glitch as not just a failure to perform, but a conscious refusal. She proposes that identities and action formerly defined as “error” can be redefined as glitches that expose gaps in the digital reality that is often assumed to be unquestionable in its function and goals.

Watch & Reflect: Sondra Perry

The interdisciplinary artist Sondra Perry (born 1986) often manipulates and exploits features in Open Source software like Blender and Chroma Key compositing to explore the intersections of race, identity, community, capitalism and technology during what we might still call the Digital Revolution. Listen to this video interview, where Perry discusses some of her projects with curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, “Sondra Perry: Typhoon coming on” Creator: Serpentine Galleries, Source: YouTube.com (2018) (14:26 minutes).

Questions to Consider

- What are some of the ways Perry exploits operator errors in Blender, like the purple/pink texture, to convey ideas?

- How does Chroma Key blue add meaning to Perry’s work? How does she use Chroma Key blue and green differently than other artists working in video production?

- How do Perry’s installations allow us to reflect on our own use of screens and the different viewing experiences made possible by different types of screens?

- Perry often uses the physicality of video, making objects we might call sculptures, like the exercise machines. What artists from previous chapters work similarly with video? (Think particularly about what you learned in the Early Video Art and the Digital Video Art and Video Installation chapters.)

- What are some of the most significant ideas explored by Perry in her work?

- In what ways does Perry’s art challenge the status quo, an Element of New Media Art?

- In Perry’s installation Typhoon Coming On, how does Perry use both the ocean modifier in Blender and a historical painting by British artist J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) to examine the history of slavery?

- What does Perry mean by saying “making new futures requires looking back”?

Explore & Consider: Glitch

Examine the following web projects and consider the questions listed below while examining each site and each project.

- A Refusal, by American Artist (2015-2016). online performance.

- Afro Cyber Resistance(2014), by Tabita Razaire (born 1989). video collage. Read more about Rezaire’s war against digital colonialism in this article, We’ve Become Cyber Slaves! Okay Africa.

- Clickistan, by Ubermorgan.com (2010). web project.

- jodi.org My Desktop OS X 10.4.7 (2007) (Click a lot on Jodi.org, also watch this video of the page on Ubu.) web project.

- They Rule, Josh On (2004). See also the They Rule project on the MoMA website.

- Shredder 1.0 by Mark Napier (1998). interface.

Questions to Consider:

- Spend some time reviewing each of these projects. Watch the videos, if any. Click around on each site. Describe the aesthetics of each project. What were your first impressions? What do they look like or feel like after you have spent some time with them? (Use as many specific examples as you can.)

- Are there things that seem strange about these projects? What seems exciting? Did you encounter any frustrations while exploring each project? Explain.

- In what ways is viewing each project similar to viewing a traditional work of art like a painting or drawing? In what ways is it different?

- Which of these projects would you describe as an open system? Why does it not have an end?

- The projects at the top of the list were created more recently and the projects at the bottom of the list were created in a very different media environment than our own in the 2020s. Are there some projects that resonate with you more than others? If so, explain why.

- All of these projects expose aspects of digital culture that often remain hidden. Consider which aspects of our digital world on and offline are being highlighted by each project.

Focus: NFTs

And finally, the newest development in Internet Art during the Digital / Crypto Age is the NFT (Non-fungible Token). Read the Wikipedia description of NFTs linked below. Also read the short article about the NFT market and its implications for the art world. Finally, the most famous NFT was made by an artist named Beeple, who sold the very first NFT for $69 million dollars. Read the short critical analysis of the actual images in Beeple’s NFT below.

Read & Consider: NFTs

What is an NFT? (Wikipedia entry)

Martha Buskirk, “NFT Market Feeds Our Obsession with Ownership”, Hyperallergic, March 14, 2021.

Rishi Iyengar and John Carlin, “NFTS are suddenly everywhere, but they have some big problems”, CNN Business, March 30, 2021.

Ben Davis, “I Looked Through All 5,000 Images in Beeple’s $69 million Magnum Opus. What I found isn’t so pretty” artnet.com, March 17, 2021.

Questions to Consider:

- What makes an NFT a good example of New Media Art? How are NFTs connected to the elements of New Media Art that we’ve been examining this term?

- What are some of the ways that NFTs challenge traditional ideas about what art is and what art can be?

- Does radical use of new technology, always result in important or compelling art? What are some of the problems people have with and/or the criticisms that people have raised about NFTs?

Key Takeaways

At the end of this chapter you will begin to:

- Explain the context and history of Internet Art and Web 2.0.

- Describe and compare significant pieces of Internet Art (or net.art).

- Recognize developments in art of the Digital Revolution and consider how Internet Art is connected to the broader history of visual culture.

- Explain how Internet Art and Web 2.0 relates to the elements of New Media Art.

NOTE: Chapter 14: Interactivity and Immersive Technologies is still under construction. Coming Soon!

Selected Bibliography

Acland, Charles R., ed. Residual Media. University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Bell, Adam and Charles Traub, eds. Vison Anew: The Lens and Screen Arts. University of California Press, 2015.

Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London and Brooklyn: Verso, 2012.

Bishop, Claire, ed. Participation (Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006.

Bolter, Jay Davide and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000.

Cornell, Lauren. Mass Effect: Art and the Internet in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015.

Grau, Oliver. Ed. Media Art Histories. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

Greene, Rachel. Internet Art. Thames and Hudson, 2004.

Gronlund, Melissa. Contemporary Art and Digital Culture. Routledge, 2016.

Grosenick, Uta, Reena Jana and Mark Tribe. New Media Art. Taschen, 2006.

Hansen, Mark B.N., New Philosophy for New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006.

Kholeif, Omar. Moving Image (Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art). Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 2015.

Manovich, Lev. “Avant-garde as Software“. 1999.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002.

Manovich, Lev. “The Practice of Everyday (Media) Life.” March 10, 2008.

Montfort, Nick and Noah Wardrip-Fruin, eds. The New Media Reader. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003.

Moss, Ceci. Expanded Internet Art: Twenty-First Century Artistic Practice and the Informational Milieu. (International Texts in Critical Media Aesthetics). Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.

Paul, Christiane. Digital Art. 3rd edition. Thames and Hudson, 2015.

Paul, Christiane. New Media in the White Cube and Beyond: Curatorial Models for Digital Art. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2008.

Quaranta, Domenico. Beyond New Media Art. LINK editions, 2013.

Respini, Eva. Art in the Age of the Internet: 1989 to Today. Yale University Press, 2018.

Ryan, Susan Elizabeth, “What’s So New about New Media Art?” Intelligent Agent, 2003.

Rush, Michael. New Media in Art. Thames and Hudson, 2005.

Russell, Legacy. Glitch Feminism. Verso, 2020.

Shanken, Edward. Art and Electronic Media. Phaidon Press. 2009.

Shirkey, Clay. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations. New York: Penguin. 2008.