11 Social Practice

Social Practice and New Media Art

What is art not? Who makes art and what does art making look like? What is community and how can communities be built and connected more deeply through art practice? These questions are significant for a new approach to art making that began to develop in the late 20th century, called Social Practices. Though the scope and definition of Social Practice Art is debated and constantly being redefined, it is an approach that was influenced by artists working internationally after World War II, trying to make sense of a world fragmented by violence and oppression. Many artists began to feel that social bonds were disintegrating. They proposed art as a force that could allow people to know themselves better, forge new social connections and provide alternatives to the alienation pervasive in the modern world.

We’ll explore the history and ancestors of Social Practice Art in this chapter, but first, let’s consider contemporary artists who employ a variety of mediums and strategies to engage communities in their art practice. Keep in mind that some of the artists we’ll look at in this chapter don’t use the term “Social Practice” to describe their art. This term is a good example of historians and critics trying to make sense of related impulses and approaches. Labels like “Social Practice” come with a danger of limiting our understanding of an artist’s work. As we have seen, most of the artists featured in this book have made work that expands the limited boundaries of our chapter headings. This is also true for the artists featured in this chapter.

Contemporary Artist: Theaster Gates

One example of a multidisiplinary artist, whose work engages with Social Practice ideas, is Theaster Gates (born 1973). Gates came to art as a potter, creating vessels. In 2009, he bought an abandoned building in the South Side of Chicago and refurbished it considering the relationship of the building to the community around it. In the abandoned building he created a library, a slide archive, and a soul food kitchen, and maintained versatile spaces for a variety of community activities.

One building followed another, each focused on culture and community gathering for those financially disadvantaged with an eye to maintaining neighborhoods, and this became known as the Dorchester Projects. The art is the activity in the buildings and the impact on the community, and Gates is the artist fostering and directing the social practice.

Watch & Consider: Theaster Gates

Watch this TED Talk by Theaster Gates titled “How to revive a neighborhood: with imagination, beauty and art. (2015) (16:56 minutes)

Questions to Consider:

- Describe Theaster Gates’ work. What kind of projects does he share in this video and how would you describe them to someone not studying New Media Art?

- What are some major themes in Gates’ work? What ideas link all of his different approaches to making art?

- What questions do you have for Gates? If you could sit down and speak with him, what would you ask him?

- What are some ways that Gates’ work is connected to life outside of traditional art institutions? What connections do you see between Gates’ work and your own lived experiences in the communities you move through?

- Describe Gates’ career development towards the way he practices art making today.

- If we’re using Gates’ work as an example of Social Practice art, what are some ways you might describe Social Practices after listening to Gates talk about what he does?

What is Social Practice Art?

Social Practice Art, also called Relational Aesthetics by the French curator Nicholas Bourriaud, has its origins in the mid 1990s, when many were exploring new connections and new global communication online. It therefore seems significant and perhaps unsurprising that Social Practice Art centered and continues to center social engagement is an art medium. Human relations became the content of Social Practice art, instead of a story or qualities of objecthood. The meaning of the work is often found in the situation rather than in an art object. Because of this, Social Practice remains outside of the art market. It is difficult if not impossible, to buy and sell. Social Practice art also often defies or exists outside of the visual analysis approach you read about earlier in this book. So Social Practice in art — rather than being about an art object and the viewer’s response to it — is grounded in participation, especially participation that revolves around a recognition of or critique of communal relationships.

Social Practice is an integration of art and life. Social Practice is sometimes considered more democratic than other art forms because it doesn’t privilege the artist, viewer, curator, or even the collector. It challenges traditional art historical hierarchies, especially the role of artist. Social Practice insists on community, founded in work that is collective rather than individual. Additionally, some Social Practice artists use psychological and sociological approaches to explore human interaction. In fact, many Social Practice artists work across disciplines, connecting art with fields such as linguistics, math and the sciences.

Artists embracing a social practice as their artistic practice may be interested in breaking down what they see as false distinctions between art and life, resulting in collaboration with people in a variety of disciplines as noted above. Social Practice also acknowledges that art happens outside of a traditional art studio. This Post Studio approach allows social practitioners to make interventions into daily life, often documenting them and sharing them beyond the commercial gallery system. Social Practice artists might also collaborate with makers and creators who are not considered part of the art world, challenging the distinction between “professionals” and “amateurs”.

You might have begun to realize that Social Practice Art is related to other approaches discussed in this book, most notably, Institutional Critique. While Social Practice art explores social interactions and relationships in ways not explored by Institutional Critique, both approaches may engage in critique of art institutions and the discourse surrounding art. Social Practices and Institutional Critique, both often take a critical approach to institutions beyond the art world, exposing systemic inequities at their core.

Like Institutional Critique, Social Practice Art does not rely on traditional art forms and materials. So this approach to art making might involve organizing events or engaging in activism, rather than painting or sculpting. Moreover, Social Practices deny traditional modes of presentation and audience reception, opting instead for engagement outside of traditional art institutions. With Social Practice approaches, the audience has agency and becomes an integral part of the creative work.

Elements of New Media Art

Now that you’ve read a little bit about Social Practices, look back at the Elements of New Media Art you read about in the Introduction. Which Elements of New Media Art relate to what you’ve learned about Social Practice Art so far?

Contemporary Artist: Suzanne Lacy

Suzanne Lacy (born 1945) is another contemporary artist who has been working for decades in different communities and whose work can be considered Social Practice, though as she notes, she and others having been making socially engaged art before the term “Social Practice” was coined. Let’s watch a video in which Lacy explains her practice, her focus on feminist activism and community and her use of time as an artistic material.

Watch & Consider: Suzanne Lacy

Watch “Suzanne Lacy: We Are Here,” May 2, 2019, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Source: YouTube. (3:12 minutes)

Questions to Consider:

- How does Suzanne Lacy describe Social Practice Art?

- Lacy use a variety of different mediums in her work, because the concept is more important than the material or what the work looks like. What others works of art have you read about in earlier chapters that have a similar focus on ideas over form?

- She also explains that the primary material she works with is time. What do you think she means by that?

- What does she say about the relevance of Social Practice art today?

Now watch “Suzanne Lacy – ‘The Invisibility of Older Women’ | The Tanks,” August 3, 2012, Tate. Source: YouTube. (4:26 minutes)

In 1987 The Crystal Quilt performance directed by Suzanne Lacy in Minneapolis, Minnesota, culminated three years of a public project focusing on empowering older women. Read about the project here “Suzanne Lacy: The Crystal Quilt,” from the Tate Modern and watch the explanatory video posted below. Consider how participation, time, traditional materials, and technology all contribute to meaning in this work

Questions to Consider:

- How does The Crystal Quilt project combat the invisibility of older women, according to Lacy?

- Lacy also notes that this project explores the leadership capacity of older women, after watching this video, what do you think she means?

- What does Lacy say about the challenges of exhibiting a time-based work of art like The Crystal Quilt in a museum?

- Why do you think she chose to reference a quilt in this project?

- What does Lacy say about the responsibility of an artist who is working with social issues in their art?

Focus: Historical Threads of Social Practice Art

What inspired this approach to making art? Well, people have been communicating creatively and building community since prehistory, so we could trace the origins of Social Practice Art to earliest known communities. After World War I ended in 1919, in part because of their experiences in the war, artists began to use diverse practices to raise questions about society and about what art is. Dada artists in Europe embraced absurdity as a protest to “rational” thought that had led to World War I. Dada artists invented new ways of making art and began to suggest that art could encompass ideas as well as objects. The bizarre and nonsensical performances, sculptural objects, and printed publications, posters and pamphlets became a staple for this movement as it spread around the world to the United States, Germany, France, Russia, Romania, and Japan among other countries. The work was usually playful and often a cultural critique focused on irrationality, chance, imagination, and integrating art and life.

The artist Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) embraced Dada approaches in his own practice and challenged traditional materials and artistic processes with projects like his Readymades. As you read about in the introduction, Duchamp made Readymades by taking non-art objects that had already been made, removing them from their original context and inserting them into the art world, in part to emphasize the importance of context. With his Readymades, Duchamp challenged the traditions of art and laid the foundation for Conceptual Art decades later. Readymades also opened the door for New Media Art and Social Practices by suggesting that art does not have to be about skill, materials or form. Instead, art can be about an idea, or what is being said.

John Cage and Black Mountain College

Marcel Duchamp was later part of and an influencer at Black Mountain College in Asheville, North Carolina, a progressive arts school that a number of American artists attended in the 1950s. Composer John Cage (1912-1992) also taught at Black Mountain College and in his own work was inspired by Duchamp’s idea of the Readymade. Cage emphasized the conceptual and argued that art could encompass actions and ideas as well as objects. Cage influenced young artists who began to find inspiration in the world outside of their studio.

And this idea is clearly expressed in an early work by Cage, first performed at Black Mountain College in 1951 and then performed publicly in Woodstock, NY in 1952, by musician David Tudor (1926-1996). The piece was titled 4’ 33” (4 minutes and 33 seconds) indicating the duration of the composition. To perform the piece Tudor entered the stage, sat at a piano, opened and closed the lid indicating three movements, and exited after 4 minutes and 33 seconds. While there were no deliberate sounds made, Cage explained that this piece is not about silence. According to Cage, “There is no such thing as silence. Something is always happening that makes a sound.” In a 1957 lecture on Experimental Music, Cage described music as purposeless play and an affirmation of life. Not an attempt to bring order out of chaos, but a way of waking up to the very life we’re living.

Stop & Reflect: John Cage

The John Cage Trust developed an iPhone App to record and share your own version of 4’ 33” (4’ 33” App for iPhone). Use the app to record your own version of 4′ 33″. Listen to other versions on the app if you like.

- What are some of the differences between your version of 4′ 33″ and the other versions you listened to?

- Imagine listening to David Tudor’s performance in 1952. What sounds might you have heard in 1952 New York that you didn’t hear in your version today? What sounds did you hear today that might not have been present in the first performance?

- What are some things that digital technology and the development of this app have added to this work of art that Cage may not have originally conceived of in the 1950s when he composed this piece?

- In what way does a work like this challenge traditional ways of thinking about what art is?

- What are some connections between this piece and some of the Elements of New Media Art we’ve been exploring in this text?

Happenings

In the late 1950s and the early 1960s in the United States, artists began creating installations and staging events in environments, questioning the parameters of the art gallery and traditional definitions of art. Influenced in part by Japanese avant-garde artists like the Gutai Group, who exhibited in Europe and the US in 1957; and also by John Cage, these artists influenced many developments in New Media Art and paved the way for both later performance artists and social practice work.

The artist Allan Kaprow (1927-2006), for example, began to think that making paintings in single, flat rectangles to hang on walls, no longer made sense. So he started making art out of the environment, embracing the entire world for use in his art. He coined the term Happenings to describe the work he began to do. Explaining that Happenings were a new art form, a new media, involving groups of people participating in intermedia performances. These Happenings began to actively blur the lines between art and life and between audience and performers. You can read examples of some other Happenings authored by Allan Kaprow in the Performance Art chapter of this text.

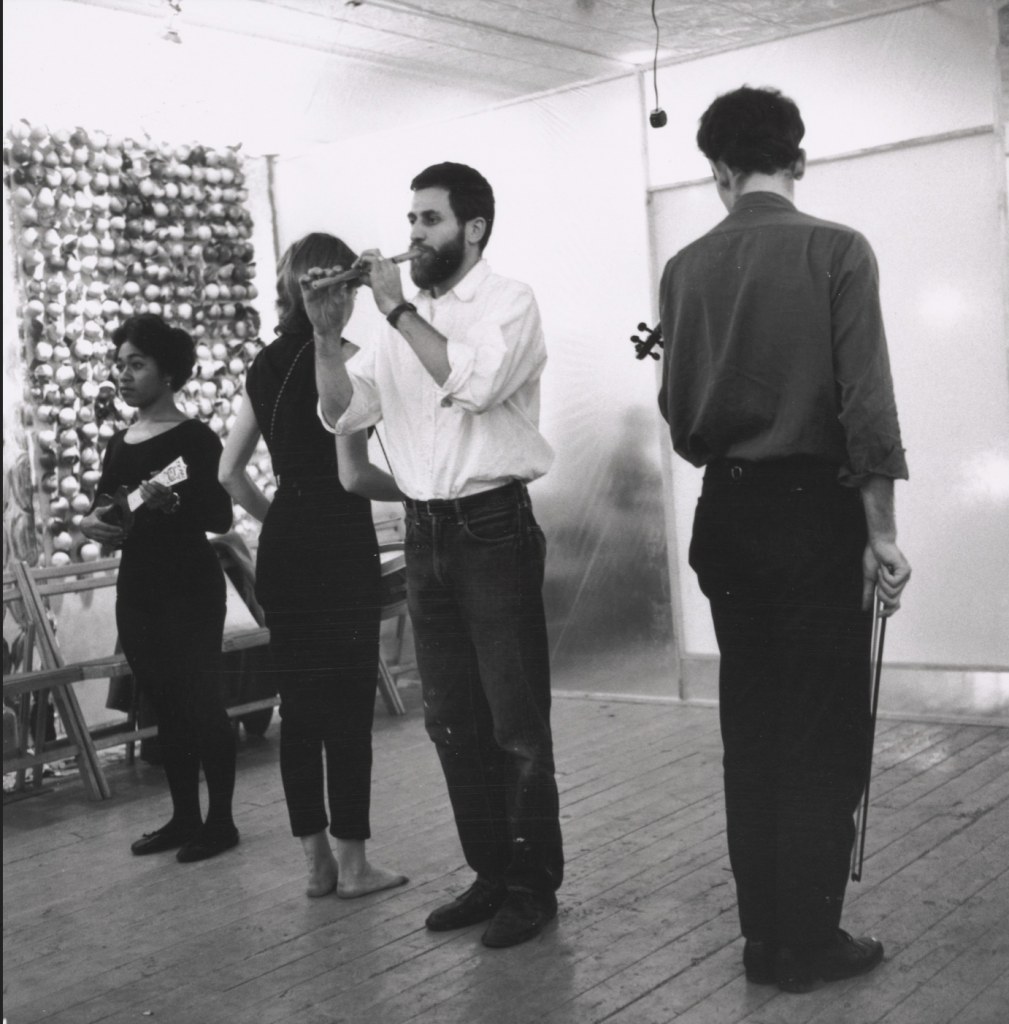

Kaprow’s 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, was first performed in 3 rooms in a New York gallery in 1959. Attendees were given 3 small cards when they arrived with instructions to move to a different room each time a bell rang. There was a different Happening per room for each of the 6 parts, so no one person would be able to view all 18 Happenings. Some of the Happenings included things that might traditionally be associated with performance like people playing instruments (pictured here). Others featured tasks not often considered performative like squeezing oranges to make juice.

Kaprow saw art as a medium that could enhance our understanding of human psychology, sociology, aesthetics and politics. And thus his work has had a direct influence on some contemporary artists interested in Social Practices. In a statement looking forward to the approach of many artists who make work considered New Media Art today, Allan Kaprow explained, “The young artist of today need no longer say “I am a painter” or “a poet” or “a dancer.” He is simply an “artist.” All of life will be open to him.”

Fluxus

The international art group, Fluxus, also had a major impact on Social Practice Art and other approaches to New Media. Many Fluxus artists were students of John Cage at Black Mountain and at the New School for Social Research. And from Cage, they learned how to look at the world in an open-ended way and break down the distinction between art and life. As Fluxus artist Ben Vauthier (born 1935) explained, “Without Cage, Marcel Duchamp, and Dada, Fluxus would not exist…. Fluxus exists and creates from the knowledge of this post-Duchamp (the ready-made) and post-Cage (the depersonalization of the artist) situation.”

The name Fluxus references change, transformation, fluidity, and the group believed that “everything is art and everyone can do it.” George Maciunas (1931-1978), the founder of Fluxus, wrote the Fluxus Manifesto in 1963 reacting against traditional and Modern art and stating the Fluxus promotes living art and art that can be grasped by all people, not just art critics and collectors. Fluxus artists argued that art doesn’t only have to be concerned with formal qualities. Art can be about ideas. Art doesn’t have to heroize the individual. Art can instead be about the world around us. Art can be about community and interpersonal connections. Finally, Fluxus artists also argued that art could be an experience rather than a commodity.

To make art that couldn’t be bought or sold, Fluxus artists, including artists you’ve already encountered in this textbook, like Nam June Paik (1932-2006), did things like leading Free Fluxtours of neighborhoods in New York City. They developed a Flux-Sports event that featured contests like a 100 yard race while drinking vodka, a 100 yard candle carrying dash and crowd wrestling in confined spaces. And they wrote Event Scores that often celebrated the unpretentious pleasures to be found in everyday life. You can read about an iconic Fluxus Event Score written by the Fluxus artist Alison Knowles (born 1933) in the Performance Art chapter of this book. What are some differences between Fluxus Event Scores and other approaches to Performance Art shared in that chapter?

Questions to Consider: Happenings and Fluxus

- What are some differences between attending a traditional play in a theater vs. attending a Happening like 18 Happenings in 6 Parts?

- What are some differences between Happenings and Fluxus Event Scores?

- In what ways do both Happenings and Fluxus Event Scores challenge traditional ways of viewing art in a gallery?

- How do these pieces expand what it means to be an audience member or viewer?

- How do these pieces expand what it means to be an artist?

- In what ways do these approaches blur the lines between art and life?

- Which of the Elements of New Media Art do see present in these mid-century expansions of traditional art media?

Joseph Beuys and Social Sculpture

The artist Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) was a leading figure in the European avant-garde after World War II ended and as an artist from Germany, his work often dealt with the legacy of Nazi fascism and his belief that a major cultural transformation was needed and that art could play a vital role in that transformation. He was a politically active artist, who also worked with Fluxus and produced significant early Performance Art that he called “actions”. But his most significant influence on Social Practice Art is his concept of Social Sculpture.

Beuys argued that we shouldn’t see creativity as the special realm of artists. He felt that everyone could (and should) apply creative thinking to their own area of specialization, whether that be law, education, physics, epidemiology, homemaking, or the visual arts. He saw Social Sculpture as a conscious act of shaping, of using creativity to bring a chaotic and perhaps oppressive aspect of the world into a state of new form. His expansion of the definition of art and his argument that all humans can engage with creativity have informed many Social Practice approaches.

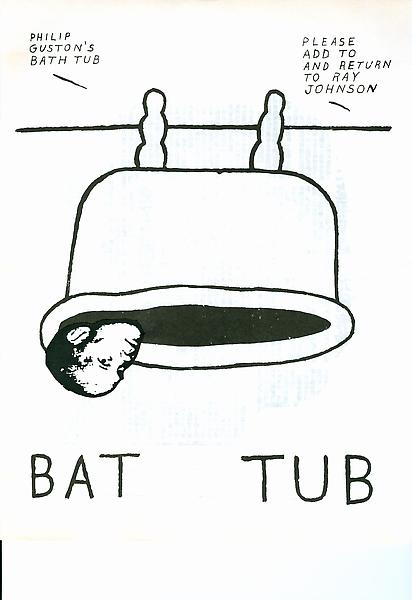

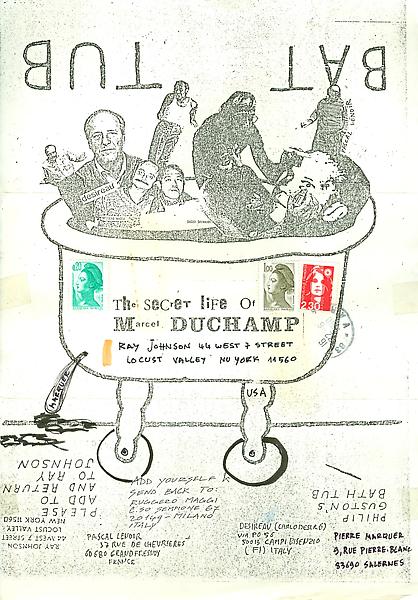

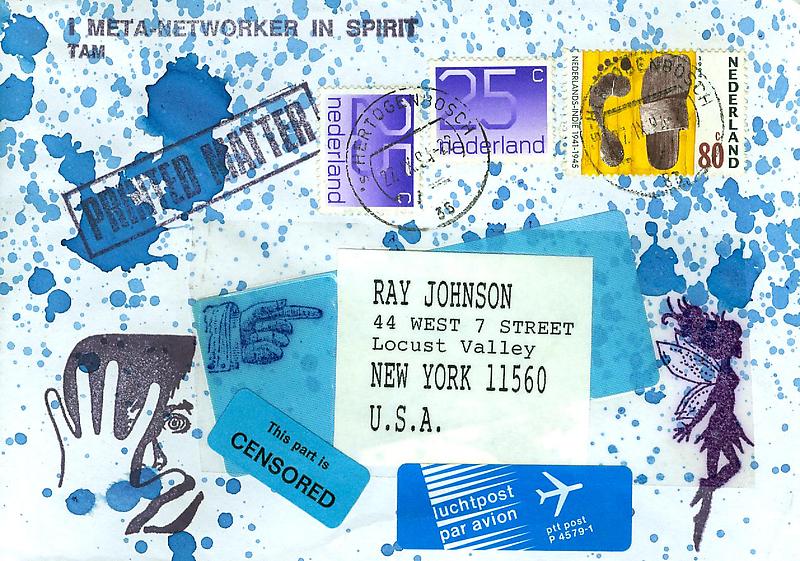

Mail Art (Correspondence Art)

Tied to Fluxus and Conceptual Art, Mail Art or Correspondence Art is another mid-20th century genre that contributes to Social Practice in Art as it is practiced today. In the 1950s, Ray Johnson (1927-1995) began using the United States Postal Service to mail letters and postcard-sized works to friends in order for them to add their contributions and continue the correspondence. The works involved stamping, mimeographing and photocopying, drawing, writing, collaging and exchanging the works with others around the world. The often-collaborative works could be mundane, silly, nonsensical, tongue-in-cheek, and/or thought-provoking communication. Ray Johnson named his network “The New York Correspondence School of Art” in the 1960s, and by the 1970s, Mail Art was included in organized exhibitions around themes and published works with the exchange of art burgeoning around the world. The Mail Art movement is also a predecessor of Zine culture in the 1990s and a predictor of many developments in social media.

Stop & Reflect: Mail Art

You can participate in a Mail Art project too. Check out this clearinghouse of mail art projects and exhibitions for ideas on how to participate.

While examining the Mail Art projects linked above, consider the following questions:

- What are some of the ways that Mail Art challenges traditional ideas about what art can be?

- How is Mail Art different than traditional art media? How is it related to New Media Art?

- What are some of the Elements of New Media Art that you see present in Mail Art concepts?

- Where do you see elements of Mail Art present online today?

- What Web 2.0 or social media sites allow for meaningful creation and interaction amongst users? Are there sites that promise meaningful interaction, but also have barriers in place that thwart it? Are there sites that promise meaningful creation, but also control the aesthetic in such a way that hampers users’ abilities to create?

- What other links can you make between Mail Art and types of interaction online today?

Situationist International

These influences on Social Practice Art are also related to approaches developed by a group of avant-garde French artists and activists who called themselves The Situationist International or SI. The Situationists criticized postwar capitalism and the “bureaucratic society of controlled consumption” that one of their leaders Guy Debord (1931-1994) labelled the “Society of the Spectacle.” In 1967, Debord published a book of the same title, in which he applied Karl Marx’s theory of commodity fetishism to the mass media. Marx explained how commodities are disconnected from their maker and how they are made and individuals are disconnected from their own labor value in the modern market. Debord added to this critique by explaining that humans are also disconnected from authentic lived experience in this spectacularized world.

Many of John Cage’s ideas are related to the approaches the Situationists developed to challenge the spectacle. One approach they developed is called the Dérive, which translates to “drifting” in French. Going on a derivé requires someone to drop their typical motives for travel and allowing themselves to be pulled in new directions. A dérive might give someone the opportunity to see an area they see often in new ways and to travel through parts of a neighborhood or city in ways that subvert controlling structures like sidewalks, paths and traffic lights that force specific paths through a space. Examples include selecting a train randomly and taking it to the end of the line, or using a map for one city to try to navigate another city of the same size. The artist Khris Soden provided a tour of Portland, Oregon using a map of Tilburg, Netherlands for the Portland Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA) Time-Based Arts Festival (TBA) in 2008, inspired by this Situationist strategy.

For the Situationists, the dérive could provide a subversive relationship to everyday life in late capitalism. Situationists felt that all citizens had the potential to be active and should not be reduced to the status of passive onlookers. The group influenced Social Practice Art, in part through their interest in providing ways for people to subvert the status quo and expose the spectacle as an oppressive and flawed picture of modern life. The Situationists thought that the best way to revitalize culture was to help everyone escape from their role as passive onlookers, so their strategies can also be considered precursors to many significant approaches to New Media Art and related to some elements of Web 2.0, which theoretically allows users to generate their own content and interact with each other in meaningful ways, rather than simply consuming content created by others.

Focus: Contemporary Social Practice

As we conclude this chapter on Social Practice in Art by looking at more contemporary artists engaging intentionally in the social realm, think about ways in which the work is participatory, exploring human relationships, and attempting to break down the barriers between art and life.

Miranda July and Harrell Fletcher

In 2009 a few years before Facebook became the largest social media network in the world and a few years before the selfie became a standard in photography, artist and filmmaker Miranda July (born 1974) installed a series of sculptures and pedestals in a grassy area of Venice, Italy during the Biennale di Venezia. Knowing that tourists would visit with cameras in hand, she designed the works to encourage social interaction. Visitors posed with and on the works, making photos to share around the world.

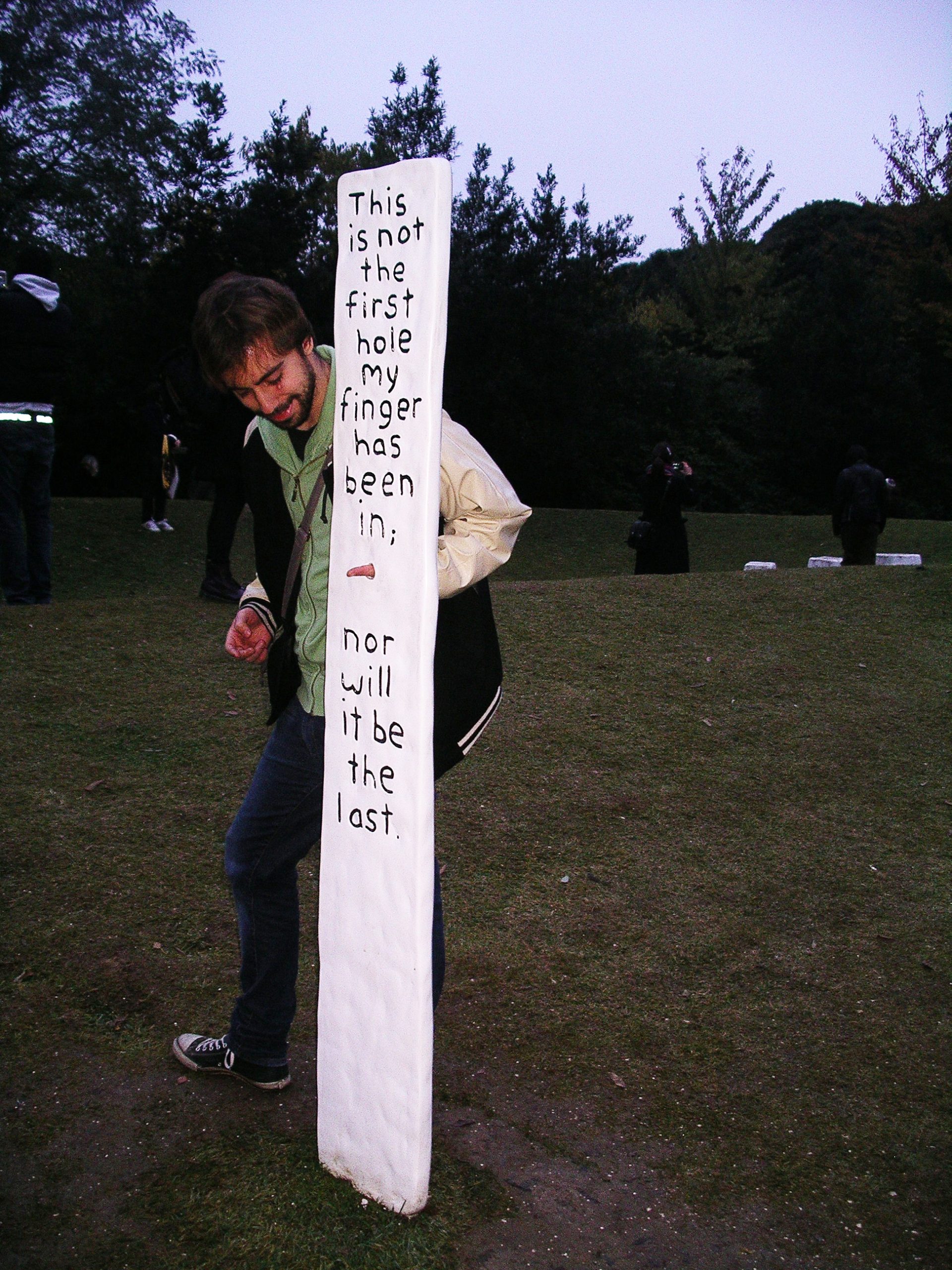

Prior to 2009, Miranda July used Social Practice as a lens for earlier work like Learning to Love You More made with Harrell Fletcher (born 1967) from 2002 to 2009. Participants were given instructions to perform a numbered task like “#69. Climb to the top of a tree and take a picture of the view” or “#63. Make an encouraging banner.” They were asked to record the task, usually through a photograph, and to send it to the artists. July and Fletcher then shared the results of the assignments on their website http://learningtoloveyoumore.com/. Subsequently, the website was acquired by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. In addition to this foray into web-based art, the work anticipates the eruption of social media, and is founded in the significances of human interaction.

Other projects by Harrell Fletcher, July’s collaborator on Learning to Love You More, include The Sound We Make Together, 2003, video projection and poster series

Tania Bruguera

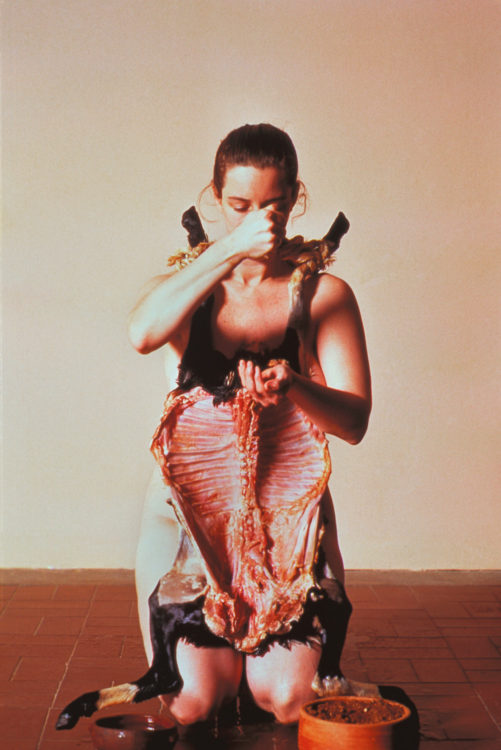

Tania Bruguera (born 1958) is a Cuban visual, performance, and social practice artist. Her work is often political in nature criticizing, for example, the lack of free speech under Fidel Casto’s rule in Cuba. Bruguera uses non-traditional art-making materials in her work: dirt, salt, her own body, hair, and animal flesh to make connections between life for Cubans during colonization and after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Burguera also developed a concept she calls the social body, meaning that she sees her body not only as her own, but as representing Cuban people and Cuban history, collectively. Her body takes on the burden of this history, collapsing time and space and revealing the lack of freedom afforded to the Cuban people, across centuries.

Many artists doing work described under the umbrella of social practices do not use that term to describe their work. Bruguera prefers the term Behavior Art, which she describes as moving beyond art historical categories and connecting art more directly to a sociopolitical agenda. She writes in “Arte de Conducta” on her website that Behavior Art retains the utilitarian potential of art. Rather than art rendered “ineffective” by its placement in an institution, like a museum with its focus on formal qualities or visual elements, Bruguera envisions art living outside the white walls and on the streets with people.

Questions to Consider: Social Practice Art

- Why is Social Practice Art related to New Media Art? (Use the Elements of New Media Art to help answer this question.)

- In what ways is Social Practice art related to Web 2.0? (For example, sites and apps like YouTube, Wikipedia, Instagram, TikTok, etc.)

- How does Social Practice Art challenge traditional ideas about art?

- What are some differences between Interaction, Participation and Collaboration? Consider some forms of media and/or art you have experienced that allow interaction. Then consider some forms of media and/or art you have experienced that require collaboration. What are the differences?

- Are there examples of interaction where you can’t really change the outcome or the work of art? Are there examples of interaction where you meaningfully change the work? Or is collaboration a better way of describing that meaningful change?

Key Takeaways

At the end of this chapter you will begin to:

- Explain the context and history of Social Practice Art.

- Describe and compare significant Social Practice projects.

- Recognize developments in Social Practices and consider how this approach to art is connected to the broader history of visual culture.

- Explain how Social Practice Art relates to the elements of New Media Art.

Selected Bibliography

Bendik-Keymer, Jeremy. “We Need to Talk about Social Practice“. e_flux. March 2019.

Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London and Brooklyn: Verso, 2012.

Bishop, Claire, ed. Participation (Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006.

Bishop, Claire. “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics”. October 110. Fall 2004. pp. 51-79.

Bishop, Claire and Boris Groys. “Bring the Noise“. Tate etc. Issue 16. Summer 2009.

Bourriaud, Nicholas. Relational Aesthetics, Les Presses Du Reel. 1998.

Chaka, Kyle. “WTF is… Relational Aesthetics?” Hyperallergic, February 8, 2011.

“Fluxus Means Change: Jean Brown’s Avant-Garde Archive“. Getter Center exhibition. September 2021-January 2022.

Fluxus and Happenings Resources from Electronic Arts Intermix. www.eai.org.

Folland, Dr. Tom and Dr. Leta Y. Ming, “Conceptual Art: An Introduction,” in Smarthistory, January 10, 2018.

Harris, Dr. Beth and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Marcel Duchamp, Fountain,” in Smarthistory, December 9, 2015.

Helguera, Pablo. Education for Socially Engaged Art: A Materials and Techniques Handbook. New York: Jorge Pinto, 2011.

Kaprow, Allan. How to Make a Happening. (Transcript of a record published in 1966 by Mass Art Inc.) Primary Information. 2009.

Knowles, Allison. Fluxus Event Scores. www.aknowles.com. (Accessed 1/08/2022)

“Lady Madonna: the Woman with One Thousand Names,” Mail Art Exhibition, May 13, 2018 – January 6, 2019, Jheronimus Bosch Art Center, Hertogenbosch, Netherlands. website.

Mail Art Projects, blog, calls for entries for mail art exhibitions clearinghouse.

Morgan, Tiernan and Lauren Purje. “An Illustrated Guide to Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle“. Hyperallergic. August 10, 2016. Web.

Parallel University (founded in 2007)

Phillpot, Clive and Jon Hendricks. Fluxus: selections from the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection. Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Catalogue. www.moma.org. 1988.

Ray Johnson Estate, “Mail Art and Ephemera,” archive catalogue. Last updated 2021.

Reyes, Jen de los. Open Engagement Facebook Page.

Ruud Janssen, International Union of Mail-Artists, website.

Shirkey, Clay. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations. New York: Penguin. 2008.

“Socially Engaged Practice,” Art Terms glossary, Tate Gallery. 2021. Web.

Stimson, Blake and Gregory Sholette, eds. Collectivism after Modernism: The Art of Social Imagination after 1945. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 2007.

Stokes, Rebecca. “Rirkrit Tiravanija: Cooking up an Art Experience,” Inside/Out, Museum of Modern Art, video, runtime 3:22 min.

Thompson, Nato and Gregory Sholette, eds. The Interventionists: Users’ Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life. Cambridge: The MIT Press. 2004.

WockenKlauser. “From the Object to the Concrete Intervention“. wochenklausur.at.

Zucker, Dr. Steven and Sal Khan, “Art as concept: Marcel Duchamp, In Advance of the Broken Arm,” in Smarthistory, December 8, 2015.