7 Early Video Art

Video Transforms Art

Very similar to how the introduction of photography and film challenged the definition of what is called art, the advent of video begged not the question of “Is this art?”, but rather “How will video transform art?” The technology of photography received its first artistic recognition for its application to existing art forms, a reason why many of the first photographs are still life images, such as Louis Daguerre’s (1787-1851) Still Life with Plaster Casts (1837).

Elements of New Media Art in Video Art

As you explore the early history of video art in this chapter, notice when you recognize these elements of New Media Art.

- Expanding the definition of art

- Exploiting new technology for artistic purposes

- Democratizing access to art

- Merging new media with old media

- Time – unfolding over time

- Liveness – happening in real time, the artist is there

- Variable – always different, changing

- Interactive – viewers are involved and can change and manipulate the work

However, as video entered the visual arts, there were many other forms of visual expression, such as Minimalism, Abstract Expressionism, Dada, found object sculpture, Fluxus, film, performance art, feminist art, Situationist International, and many other movements. Video, like an objective tool, was used to extend expression in diverse fields, which were by no means mutually exclusive. For this reason, it becomes difficult to follow the developments in early video simply chronologically or only by its application in various movements. A delineated analysis may seem chaotic, but there is no clean and simple manner of representing postwar cultures. The use of video art came naturally in artists in the postwar landscape with not only consumer level affordability and access, but its language was familiar to most households.

As Pop Art made it abundantly clear, mass culture came to define America in the 1960s and the television was one of the more the ideal forms of media to hijack. Many artists in diverse backgrounds and goals tasked themselves during this time with deconstructing images and imbuing them with new, subversive meaning and having video in their toolkit opened a whole new world of possibilities. Video was taken up as a rich source of content ripe for appropriation and it proved itself useful for image manipulation, documenting happenings and performances, and even instrumental in installations.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Fluxus artists seemed particularly drawn to the medium. One of the first, significant works to emerge under the umbrella of the video art was TV Dé-collage, a series of events produced by the German artist Wolf Vostell (1932-1998) under the umbrella of installation art. The sculptural space in this case was the window of a Parisian department store, where he placed television sets on desks and furniture, displaying warped images. Since the late 1950s Vostell began experimenting with various forms of manipulation and, to some degree, disruption of visual messages in mass media from mass produced publications to billboards displayed for the masses. The leap then to integrate television sets into his works came naturally, which found powerful functional and symbolic expression in images, assemblages, installations, and sculpture.

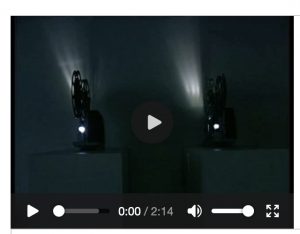

Another direction that some video artists were taking their installations was to activate spectators into participating in the artwork. In Slipcover (1966) by artist Les Levine (born 1935) used a series of monitors to present spectators with recorded footage of themselves, which, for many, was an unsettling and exhilarating experience. The ability to shape spaces for and depend on the viewer to elicit a specific feeling was a powerful prospect and one that artist Bruce Nauman (born 1941) seized in his 1968 work Video Corridor.

This installation consisted of two parallel, floor-to-ceiling walls that created a narrow tunnel with two monitors at the end. As the viewer walked through the claustrophobic corridor that arrived at the screens only to find them streaming surveillance video of the viewer. The confines of the space paired with the displaced perspective aims to disorient and even instill fear into the viewer.

Expanding Video into the Arts

Initially, the television served Fluxus artists across the world throughout the 1960s like a prop in installations and mixed media sculpture to critique the new, vapid culture surrounding television. However, the use of video quickly expanded into other fields, like performance art, and gained recognition as a medium in its own right. Artists and critics alike were already questioning whether artworks need be limited to physical objects in the first place and video assumed an important role in this transition. An early adopter of video, US artist Bruce Nauman linked video media with performance art and sculpture. His work Wall/Floor Positions (1968) Nauman turns his own body into the sculptural work in poses throughout his studio. This work was a natural progression that arose from his explorations in integrating new media, as was clear in the photographs of his Fountain (1967) a year earlier.

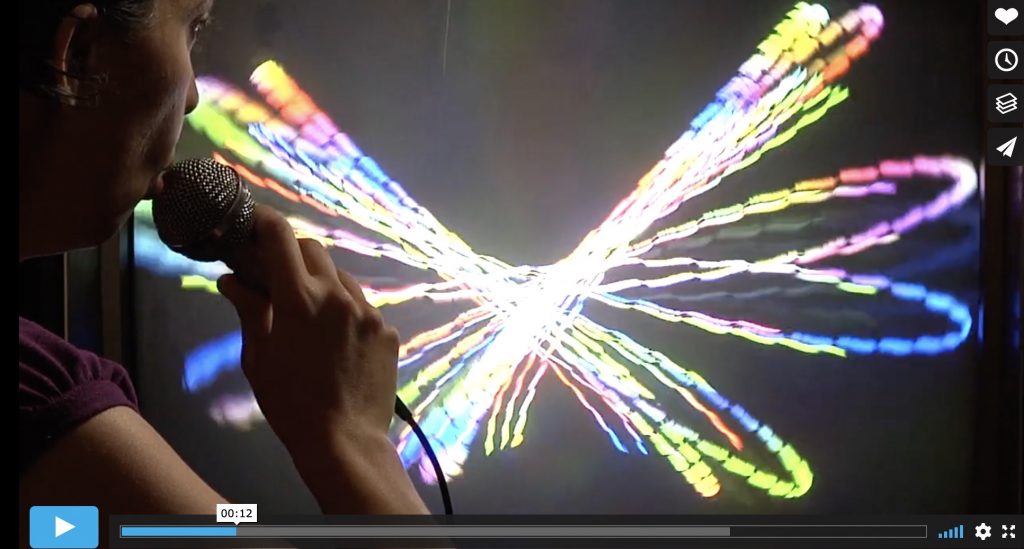

Korean artist Nam June Paik (1932-2006) began to utilize the television set and other video devices for their inherent qualities for formal expression. Influenced by his time studying with American artist John Cage (1912-1992) in Germany, Paik took an approach akin to that of a mad scientist with a touch of Eastern zen philosophy. Like a curious inventor he deconstructed the appliances to experiment with the distortion of images with magnets and the sync pulses of the displays. Taking it further, the televisions were disassembled and collaged around rooms randomly, in shapes, in seemingly non-sequitur contexts. In the video performance Participation TV (1969) Paik invited spectators to take on an active role in manipulating the performance with microphones.

With this momentum Paik followed these performances by a collaborative performance series with musician Charlotte Moorman (1933-1991) that utilized inventive applications of televisions, which attempt to both reconcile man/machine and also address contemporary social issues, such as mainstream feminism. In TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1968-69), for example two cameras are focused on Moorman’s face, which were reflected into two circular mirrors over her breasts. The simultaneous eroticization of technology and objectification of women is further explored in Concerto for TV, Cello, and Videotapes (1971). For this piece three monitors – playing pre-recorded performances by the Moorman – are stacked in the general shape of a cello, which is then played so-to-speak by Moorman, seated behind with a bow. It is difficult to single out one aspect for analysis in the work.

Clearly, there are departures from sculpture and performance art, as well as messages regarding gender and sexuality, harking back to a previous collaboration with Moorman, Opera Sextronique (1967), but the dislocation and layering of time was perhaps most important to Paik:. “It must be stressed, that my work is not painting, sculpture, ” noted Paik “but rather Time art: I love no particular genre.” Although that statement was given as early as 1962, it holds true through most of his career as Paik navigated through movements, playing often in the spaces between.

Paralleling the advancement of consumer level technologies, artists like Paik continued to push on the boundaries of artistic applications of video. In 1965 Sony introduced the Portapak, one of the first portable video cameras and within weeks artists were using them for video art. Recognizing the potential, Andy Warhol (1928-1987) became one of the first US artists to work almost exclusively with portable cameras. Several of his early tapes became content in his first double-projection film Outer and Inner Space (1965). Later in 1965, Paik and Warhol both became essentially the first spokesmen for video art with screenings. On September 29, Warhol screened his famous “underground tapes” in underground railroad space under the Waldorf-Astoria in New York. On October 4th, Paik presented Electric Video Recorder (1965) at Cafe au Go Go.

Video was able to transition from simply a means of documenting performance art to an essential medium to better connect with the audience and communicate. Vito Acconci (1940-2017) was using single-channel, black and white video for his performances throughout the 1970s. In Filler (1971) Acconci creates a very close physical space between himself and the camera on the floor inside of a cardboard box. This and many of his works to follow, like Theme Song (1973) are framed in very close quarters in order to engage with the viewer in a closer psychological connection and to enhance the feeling of voyeurism. In 1974 artist Ana Mendieta (1948-1985) released her collected series Body Tracks and her film Burial Pyramid, all works where her body becomes the focal point to elucidate feminist critique. In another vein of exploring intimacy with their own body, artist Chris Burden (1946-2015) sought to shock audiences at the expense of his own body. In the performance Shoot (1971) a bullet is shot into his arm; in Through the Night Softly (1973) he lies on his bare stomach with his hands and feet bound behind his back and drags himself through a street of broken glass. The intense, personal connection that video offered was picked up by many artists looking to communicate a visceral experience. You can find a more detailed discussion of Mendieta’s and Burden’s work in the Performance Art chapter.

In Third Tape (1976), artist Peter Campus (born 1937) presented the story of a man that transpires in three parts. First, a man’s face is presented with clear fishing line bound across his face, effectively cutting him into cross sections. Then in the second segment the viewer sees a hand place mirrored tiles across a black surface, as it slowly becomes clear from the reflections that a man’s face is looking down from above. Finally, in the last part, a man’s face looks up through a tank of water at the camera above. Slowly his face recedes into the waters.

Unfolding the Digital Landscape

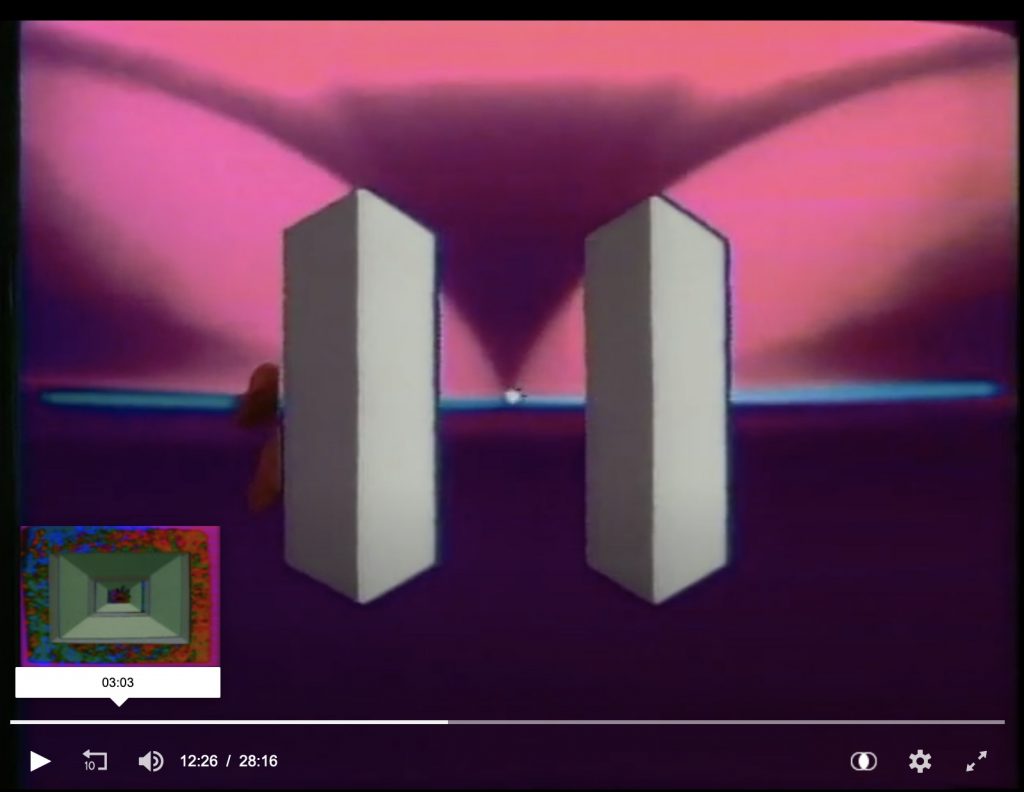

The technology of the portable camera quickly evolved from the half-inch reel-to-reel in 1968 to the more compact three-quarter-inch, color video cassettes available in 1972. In these formative years some artists were actually involved in the research and development. At its heart, the video camera is a complicated machine, a device that converts moving images into electronic signals that are transmitted to a monitor, which decodes them and reassembles them into an image to display. There are many points in that process open for manipulation. In 1970, Nam June Paik partnered with electrical engineer Shuya Abe (born 1932) to create a digital synthesizer capable of image manipulation instead of sound. Similar to revolutionary shifts in other fields of art, such as Modernist architecture or photography, the trailblazers of the art world move into areas dominated by technicians and engineers.

Elements of New Media Art

- Expands the definition of art

- Exploits new technology for artistic purposes

American painter, filmmaker, and teacher Ed Emshwiller (1925-1990) saw incredible potential in video synthesizers and computers for creating original artwork. In Scape-mates (1972) computer animation is used to render a dance of figurative and abstract visual elements in video. Indeed, the digital innovations of the 1970s ushered in a new era of image rendering. In 1973 Dan Sandin developed an image processor that is now known as the Sandin Image Processor, which accepted basic video input signals and manipulated them in a similar way that the Moog synthesizer did with audio. The device made real time modifications, making it ideal for live performances and “Electronic Visualization Events”. Another revolutionary advancement came from artist Keith Sonnier (1941-2020), who developed a forerunner to the modern computer image scanner, the Scanimate. With this he created aesthetic collages of images, like Color Wipe (1973).

In the 1980s video art took on a new dimension of real-time visualization in the form of stream-of-consciousness performance, which resonated best with Conceptual artists. Gary Hill (born 1951), for example, centered his work in linguistics, instead of music, in video art. In Electronic Linguistics (1977) the image is treated as a language that evolves. This is achieved through computer generated shapes on a screen that correlate to sound inputs. Even Nam June Paik continued to further video editing devices beyond the synthesizer that he developed with Shuya Abe. With more resources at hand Paik excelled at these creating stream-of-consciousness visual and conceptual techniques with vibrant image/music compositions such as Butterfly (1986). Works like these continued the modern and postmodern experiments in formal compositions of light and color in the digital field. Most artists working in the foundations of video art, were already members of an existing movement that did not shy away from technological change, who saw a new mode of expression and saw themselves as active participants in that change.

Consuming Video

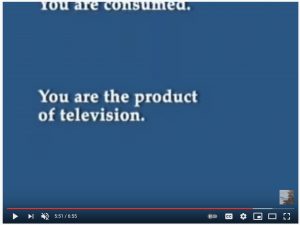

In subsequent artworks Paik also seems to personally grapple with the classic Situationist paradox of balancing an attack on television — or at least video as a medium for passive spectatorship — with weaponizing it for critique. Beyond the typical passive consumption of the television, many artists recognized that video provides a uniquely creative forum for the artist and the spectator with its ability to receive and transmit. Television, much like a radio, is capable of reciprocal communication, receiving and transmitting information. Consumers have only been sold on the idea that information can flow in one direction. A number of works in the 1970s were centered around this mythology. For one example, look at artist Richard Serra’s (born 1939) video essay Television Delivers People (1973). The video presents a scrolling text that criticizes television programming as merely corporate sponsored entertainment, a message that is underscored by a soundtrack of muzak, a bland genre of music traditionally played in elevators and malls. Also consider the video performance Media Burn (1975) by Ant Farm, an San Francisco-based artist collective. Media Burn offered a particularly interesting counter to consumer culture by stacking televisions, setting them aflame, and then driving through the stack with a 1959 Cadillac at high speed.

Many early video artists like those from Ant Farm and the New York-based collective Paper Tiger Television recognized that a new consumer society that was growing out of television and offered critique using the same medium. Often these artist activists countered mainstream television programming with their own documentaries and news reports. One collective, Top Value Television, recorded their own coverage of the U.S. Democratic and Republican conventions in 1972. Artist activists sneaked onto the main floors with their Sony Portapaks and began interviewing everyone. The resulting report was an entertaining and scything glimpse into American politics and journalism. Paper Tiger Television continued to produce a guerrilla style media counter attack on the mainstream media by producing alternative news reports for cable television well into the 1980s.

Focus: Immediacy

Elements of New Media Art

As you continue learning about the early history of video art try to identify these elements of New Media Art in the work you’re exploring:

- Variable – always different, changing

- Interactive – viewers are involved and can change and manipulate the work

- Collaborative – the artist is a facilitator and viewers make the art with them

- Time – unfolds over time

- Connectivity – made possible because of new global connections

The psychological space between the spectator became of increased interest to artists and the more it was explored, the more it proved to be an innate, powerful quality of video that artists leaned into even more, giving video more autonomy as its own art form. While exhibition space in institutions was initially given to television sets for its proximity to sculpture, the field of video art expanded quickly to fill and utilize physical space in ways that sculpture and painting could not, spilling into the realms of performance and installation art. In his live performance The Last Nine Minutes (1977) American artist Douglas Davis (1933-2014) took part in one of the first international satellite telecasts at the opening of documenta vi alongside Paik and artist Joseph Beuys (1921-1986). In this telecast to over 25 countries Davis confronted viewers with the disparity in space/time between them. One of the most significant qualities that video embodied over film was its immediacy. Films have to be treated, processed, and edited.

To create a more immersive experience, artists like Dan Graham (born 1942) were led to create multifaceted systems for specific environments, sometimes using mirrors and often employing closed circuit video setups. Graham uses these elements to surround the viewer in Performance/Audience/Mirror (1975), where he stood facing the audience, but with a mirror to his back and proceeded to describe and infer meaning from the movements of those looking on. Then he turned around and renewed the dialogue but through the filter of the mirror.

Video and mirrors work together to manipulate the relationship to the viewer in Graham’s 1983 piece Performance and Stage Set Utilizing Two Way Mirror and Video Time Delay. In this work the audience is seated facing a group of musicians with a two-way mirror between them. The musicians began to play and then a six second delayed video feed of the act was projected onto the mirror, creating a phenomenological visual and auditory kaleidoscope. The experience for the audience was effectively watching themselves and listening to the performance in real time, but having the superimposition of delayed performance all through the mediator of the mirror.

Stop & Reflect: Active or Passive Participant

The 1960s and 70s witnessed a significant reconsideration of the relationships between viewer, artwork and artist. Moving forward in this text it is important to be able to understand these relationships and, moreover, this understanding will ultimately shape how you personally navigate art in museums, galleries, in the streets, and at home. Ask yourself the following:

- How would you define an active and a passive participant in viewing art?

- Do you think that viewing a painting is an active or passive experience? Why?

For further reading: The Emancipated Spectator (2009) by Jacques Rancière. [PDF via Brown University]

Focus: Subverting the Gaze

As also discussed earlier with Vito Acconci, performance artists during the 1970s were taking advantage of video to control the level of intimacy with the audience. It was precisely this intimacy that many feminist artists seized upon for critique and video suddenly became one of the staples of the feminist toolkit. The larger theme of visual consumption was narrowed notably by film critic Laura Mulvey to analyze and critique the historical and contemporary presence of the “male gaze” in her essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975). Briefly put, spectators are commonly put in a masculine subject position with the figure of the woman on screen as the object of desire, a relationship that is referred to as “the male gaze”. The essay proved to have far reaching influence on practicing artists regarding the representation of women, far beyond the scope of mainstream cinema.

Issues of gender roles and non-binary sexuality were commonplace in art of this time and the differences in approaching these themes were vast. The technique of manipulating images (such as décollage) continued to be popular for critique of female images and the psychological intimacy between spectator and art continued with loaded sexuality. Many feminist performance artist, such as Ulrike Rosenbach (born 1943), Ana Mendieta, and Joan Jonas (born 1936), leaned early and heavily into video as a medium. One of Jonas’ most notable works Left Side, Right Side (1972) synthesized several of the aforementioned stratagems of other video artists. Her performance aimed to disorient the viewer and manipulate perspective using a camera and a mirror. Introducing a linguistic component, Jonas repeats the statements “This is my left side, this is my right side” throughout the performance. On one hand, the inversion of conventional perspective through optics reflected the artistic, mechanical interest of video. On the other hand, the use of the female body and the disruption of visual consumption clearly fit into the landscape of feminist art. The challenging mainstream portrayal of the female body preoccupied many female artists. Focusing on facial close ups, artist Hannah Wilke (1940-1993) practiced sexual gestures with her fingers and her tongue in Gestures (1973). Through the course of the act Wilke makes the gestures more and more grotesque until all eroticism has fled.

Video has been celebrated as an intensely personal medium. Explorations of the body and of the self were, as demonstrated here, not limited to women. Artist Bill Viola (born 1951) has made a career out of a life-long introspection of his spiritual and physical self. Viola started as a young artist experimenting with a young medium, a partnership suited to metaphysical self exploration. Beginning with Information (1973) Viola experimented with the introduction of an interrupting signal in his video recorder in order to produce a sequence of images that could be externally manipulated, a technique similar to that of Nam June Paik. In A Non-Dairy Creamer (1975) the viewer gazes at Viola, but through the reflection in a cup of coffee, which slowly disappears as he drinks it, a similar concept to Dan Graham’s Performance/Audience/Mirror mentioned earlier, but on a more personal level. Using the reflection and filtering of himself to represent and reconcile his self/non-self, became—in many ways—the leitmotif of his metaphysical journey in video and continues to inform even his contemporary work.

It was in his work I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like (1986) that yielded a reflection of himself in the eye of an owl, an image so powerful to him that he made it his signature mark.

If the question of video began as “Is this art?”, it certainly established itself as not only art, but an independent media. Ultimately, video offered a new, alternative media to render meaning and new ideas in space and time that was unavailable in its predecessors, like film and performance art. Time, perhaps, was the most significant characteristic of video that drew artists to it, artists seeking to identify, communicate, or simply explore art in this dimension. The ephemeral quality of video, artists would find, would make it possible to unify and dissect, to focus and obscure, to represent, to be signifier and signified.

Watch & Consider: Electronic Superhighway

As society began to approach the turn of the twenty first century, Americans were looking ahead, thinking about what kind of future awaited them. Paik predicted a new paradigm for communication, something that he called a “broadband communication network” or “electronic super highway” connecting us all. By the 1990s, his concept of electric information exchanges seemed prophetic in light of the emerging “world wide web”. Watch this video from Smarthistory about the perservation of Nam June Paik’s Electronic Superhighway.

After watching the video, consider the following questions:

- To what extent is this object purely a functional piece, communicating information, or does it have sculptural value?

- As the screens are replaced with newer technology, does the piece change in value, experience, or meaning?

- In what what does this work depend on the spectator?

Key Takeaways

At the end of this chapter you will begin to:

- Explain the historical divergences of video art from photography, collage, performance art, and sculpture.

- Identify video art as time-based, interactive and replicable.

- Discuss the employment of video art as discourse in socio-political critiques, such as Feminism.

- Analyze the techniques and characteristics unique to video art that innovatively utilize space and time.

Selected Bibliography

Hall, Douglas, and Sally jo Fifer. Illuminating Video: An Essential Guide to Video Art. New York: Aperture/BAVC, 1992.

Hill, Christine. REWIND: A Guide to Surveying the First Decade: Video Art and Alternative Media in the U.S., 1968-1980. 2nd ed. Chicago, Illinois: The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2008.

Popper, Frank. Art of the Electronic Age. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

Rancière, Jacques. The Emancipated Spectator. New York: Verso, 2011.

Rush, Michael. New Media in Art. London: Thames and Hudson, 2005.