Chapter 4 – Verbal Communication

Learning Outcomes

When you have completed this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify the role that language plays in a culture.

- Define and explain the principles of verbal communication.

- Explain why language can also be an obstacle to intercultural communication.

- Discuss the variations in communication styles.

- Articulate the differences between translation and interpretation.

How do you communicate? As we learned in our first chapter, communication is a process of understanding and sharing meaning with others. Former U.S. Senator and famous linguist, S.I. Hayakawa, believed that meaning lies within in us, and not in the words that we use. Family members, community members, school mates, and others use language as a system to teach us the rules, norms, customs, traditions, and rituals of our culture. Whether reading, writing, or speaking, being articulate is valued in most cultures, but the same is also true for listening and knowing when to be quiet. Verbal communication or language is created by the cultural experiences of the users.

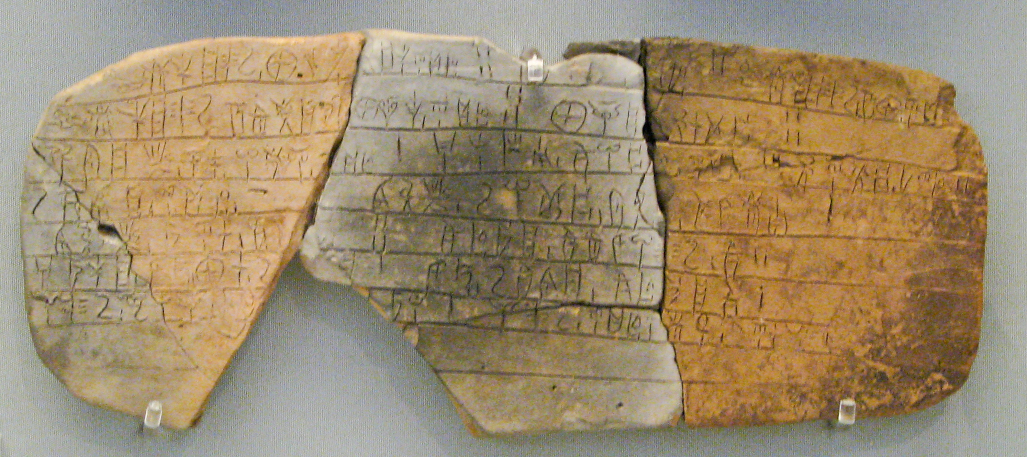

There are approximately 6500 languages spoken in the world today, but about 2000 of those languages have fewer than 1000 speakers (www.linguisticsociety.org, 2/10/19). As of 2018, the top ten languages spoken by approximately half the world’s population are Mandarin Chinese, Spanish, English, Arabic, Hindi, Bengali, Portuguese, Russian, Japanese, and Ladhna or Pundjabi (www.statista.com, 2/10/19)). Chinese and Tamil are among the oldest spoken languages in the world (taleninstuut.nl, 2/10/19).

It is estimated that at least half of the world’s languages will become extinct within the next century. Of the 165 indigenous languages still spoken in North America, only 8 are spoken by as many as 10,000 people. About 75 are spoken by only a handful of older people and are believed to be on their way to extinction (www.linguisticsociety.org, 2/10/19)). When a language dies, a culture can die with it. A community’s connection to its past, its traditions, and the links tying people to specific knowledge are abandoned as the community becomes part of a different or larger economic and political order (www.linguisticsociety.org, 2/10/19).

4.1 – The Study of Language

Linguistics is the study of language and its structure. Linguistics deals with the study of specific languages and the general properties common to most languages. It also includes explorations into language variations (e.g., dialects), how languages change over time, how language is stored and processed in the brain, and how children learn language. The study of linguistics is an important part of intercultural communication.

Areas of research for linguists include phonetics (the study of the production, acoustics, and hearing speech sounds), phonology (the patterning of sounds), morphology (the patterning of words), syntax (the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), and pragmatics (language in context).

When you study linguistics, you gain insight into one of the most fundamental parts of being human—the ability to communicate. You can understand how language works, how it is used, plus how it is developed and changes over time. Since language is universal to all human interactions, the knowledge attained through linguistics is fundamental to understanding cultures.

4.2 – Principles of Verbal Communication

Although linguistics is the study of the structure of language, as communicators, we are interested in the role of language within the study of intercultural communication. Previously we have learned that verbal communication is a living exchange of cultural meaning. As true for many areas with communication studies, there are several basic principles important to the understanding of all verbal communication. In this section, we’ll examine each principle and explore how it influences everyday communication.

Language is Arbitrary and Symbolic

Words, by themselves, do not have any inherent meaning. Humans give meaning to words, and their meanings change across time. For example, we negotiate the meaning of the word “home,” and define it, through visual images or dialogue, in order to communicate with others.

Words, in turn, have two types of meanings: denotative and connotative. Attention to both is necessary to reduce the possibility of misinterpretation. The denotative meaning is the meaning often found in the dictionary. The connotative meaning is often not found in the dictionary but in the minds of the users themselves. Connotation can involve an emotional association with a word, positive or negative, and can be individual or collective, but is not universal. An example of this could be the term “rugged individualism” which comes from “rugged” or capable of withstanding rough handling, and “individualism” or being independent and self-reliant. In the United States, describing someone in this way would have a positive connotation, but for people from a collectivistic orientation, it might be the opposite.

But what if we have to transfer meaning from one language to another? In such cases, language and culture can sometimes make for interesting twists. The New York Times Sterngold, J. (11/15/98) noted that the title of the 1998 film There’s Something About Mary proved difficult to translate when it was released in foreign markets. In Poland, where blonde jokes are popular and common, the film title (translated back to English for our use) was For the Love of a Blonde. In France, Mary at All Costs communicated the idea, while in Thailand My True Love Will Stand All Outrageous Events dropped the reference to Mary altogether. Capturing ideas with words is a challenge when the intended audience speaks the same language, but across languages and cultures, the challenge becomes intense.

Language Has Rules

Using any language means following rules. Constitutive rules govern the meaning of words, and dictate which words represent which objects (Searle, 1964). Regulative rules govern how we arrange words into sentences and how we exchange words in verbal conversations. If you don’t know the appropriate rules, you will struggle to communicate clearly and accurately with others. Consequently, others will also struggle to find meaning in your communication.

Language Evolves

Many people view language as fixed, but in fact, language constantly changes. As time passes and technology changes, people add new words to their language, repurpose old words, and discard archaic words. New additions to American English in the last few decades include blog, sexting, and selfie. Repurposed additions to American English include cyberbullying, tweet, and app (from application). Whereas affright, cannonade, and fain are becoming extinct in modern American English.

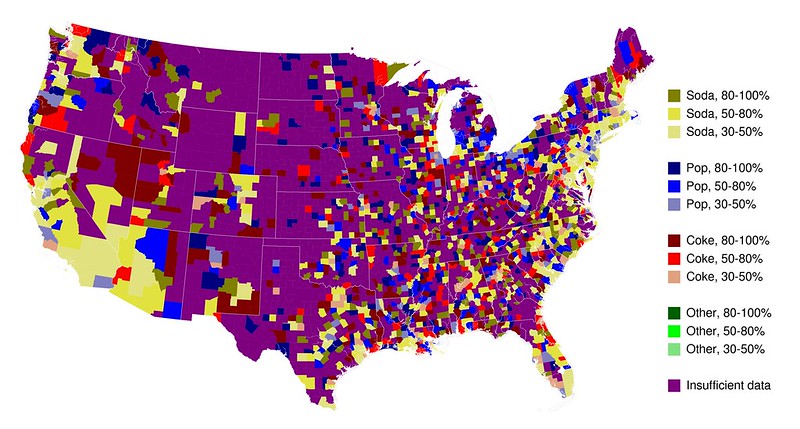

Other times, speakers of a language borrow words and phrases from other languages and incorporate them into their own. Wisconsin, Oregon, and Wyoming were all borrowed from Native American languages. Typhoon is from Mandarin Chinese, and influenza is from Italian.

Language Shapes Our Thoughts

We know that members of a culture use language to communicate their thoughts, beliefs, attitudes, and values with one another, thereby reinforcing their collective sense of cultural identity. The idea that language shapes how we think about our world was first suggested by the research of Edward Sapir, who conducted an intensive study of Native American languages in the early 1900s. Sapir argues that because language is our primary means of sharing meaning with others, it powerfully effects how we perceive others and our relationships with them (Gumperz & Levinson, 1996).

About 50 years later, Benjamin Lee Whorf expanded on Sapir’s ideas in what has become known as the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis or what is known today as linguistic determinism. Whorf argued that we cannot conceive of that for which we lack a vocabulary or that language quite literally defines the boundaries of our thinking. More modern researchers such as Derrida (1974), Foucault (1977), and Anzaldua (1987) agree. In fact, Anzaldua (1987, p. 59) states that “I am my language.” Other modern researchers (e.g. Piaget, Pinker) have noted that linguistic determinism suggests that our ability to think is constrained by language and therefore not realistic.

Regardless, of what degree our reality is influenced by language, there is no academic question as to whether language is a major influence in our understanding of culture. Because language influences our thoughts, and different people from different cultures use different languages, most communication scholars agree that people from different cultures would perceive and think about the world in very different ways. This effect is known as linguistic relativity. Your language itself, ever changing and growing, in many ways determines your reality.

Cultural Variations in Language

If your intercultural communication is to be effective, you cannot ignore the broader cultural context that gives words meaning. Cultural rules about when and how certain speech acts can be performed may differ greatly. Routine formulas such as greetings, leave-taking, thanking, apologizing and so on do not follow the same, or even similar rules, across cultures causing misunderstandings and confusion. How language is used in a particular culture is strongly related to the values a culture emphasizes, and how it believes that the relations between humans ought to be. Lack of cultural knowledge can embarrass second language learners who produce perfectly grammatically correct language but embarrassingly inappropriate sentences.

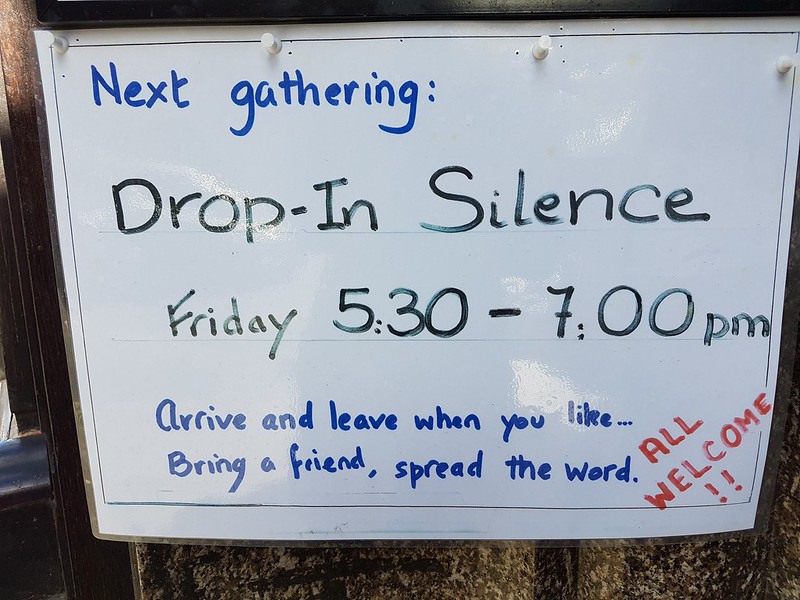

Attitudes Towards Speaking, Silence, and Writing

In some cultures, such as the United States, speech is highly valued, and it is important to be articulate and well-spoken. People in such cultures tend to use language as a powerful tool to discover and express truth and have an impact on others. These countries tend to take silence as a sign of indifference, indignation, objection, and even hostility. Silence confuses and perplexes them since it is so different from the expected behavior. Many are even embarrassed by silence and feel compelled to fill the silence with words, so they are no longer uncomfortable. Or if a question is not answered immediately, people are concerned that the speaker may think that they do not know the answer. Countries reflecting these attitudes would include the United States, Canada, Italy, and other Western European countries.

On the flip side, silence can be a sign of respect in some Asian countries. If a person asks a question, it is polite to demonstrate that you have reflected on the question before providing an answer. In differences of opinion, it is often thought that saying nothing is better than offending the other side, which would cause both parties to lose face. The prevailing thought is that sometimes words do not convey ideas, but instead become barriers. If so, then silence can convey the real intention of the speakers and can be interpreted according to the expected possibilities and a have more profound meaning than words.

There are many reasons when silence might be appropriate. For example, in hierarchical cultures (e.g. high power distance), speaking is often the right of the most senior or oldest person, so others are expected to remain silent or only speak when spoken to and asked to corroborate information. In listening cultures, silence is a way to keep exchanges calm and orderly. In collectivistic cultures, it is polite to remain silent when your opinion does not agree with that of the group. In some African and Native American cultures, silence is seen as a way of enjoying someone’s company without a need to fill every moment with noise. Or silence could simply be a case of the person having to speak in another language and taking their time to reply.

The act of writing also varies widely in value from culture to culture. In the United States written contracts are considered more powerful and binding than verbal agreements. A common question is “did you get that in writing?” The relationship between writing and speaking is an important reinforcement of commitment. Other cultures tend to value verbal communication over written communication or even a handshake over words.

Language Can Be an Obstacle

Language and verbal communication can work both for and against you in intercultural communication. Language allows you to communicate, but it can also cause misunderstanding. Clichés, jargon, and slang often present problems for intercultural communicators.

A cliché is a word or phrase that has lost impact through overuse. Sometimes clichés are considered lazy communication because people haven’t bothered to find original words to convey meaning so listeners have a tendency gloss over them. Cultural clichés can also reflect stereotypes. A cliché is something that communicators “should avoid like the plague.” (LOL)

Jargon is used by specialized groups to communicate to communicate efficiently. In other words, it is an occupation-specific language used by people in a particular profession. The medical professions information technology technicians, and gamers are well-known for their usage of jargon. Examples of jargon include contusion (bruise), sutures (stitches), cache (storage area), defrag (becomes quicker), AFK (away from the keyboard), and bullet sponge (hard to kill). For those on the outside of the group, jargon can cause confusion and misinformation so it’s always best to use common words and avoid jargon in intercultural communication.

Most of us have heard of the term slang but probably don’t realize how often we use it. Slang is the use of existing or newly invented words in particular groups. Slang differs from jargon in that it is used informally, and often changes quickly. Sometimes slang is used to tell the difference between ingroup and outgroup members. The Urban Dictionary is a great place to learn new slang.

4.3 – Variations in Communication Styles

How language is used in a particular culture is strongly related to the values a culture emphasizes, and how it believes that the relations between humans ought to be. For some time, social scientists and linguists have been studying how individuals and groups interact through language, both within the same language and between languages. They have sought to discover how and why language use varies.

If your intercultural communication is to be effective, you cannot ignore the broader cultural context that gives words meaning. Cultural rules about when and how certain speech acts can be performed may differ greatly. Routine formulas such as greetings, leave-taking, thanking, apologizing and so on do not follow the same, or even similar rules, across cultures. When communicating across cultures, an understanding of communication style differences helps to interpret verbal messages more effectively.

High and Low Context

High Context cultures, such as China, Japan, and South Korea, are those in which people assume that others within their culture will share their viewpoints and thus understand situations in much the same way. There is a great deal of emphasis on the environment or context where the speech and interaction take place. Consequently, people in such cultures often talk indirectly, using hints or suggestions to convey meaning with the thought that others will know what is being expressed. In high context cultures, what is not said is just as important, if not more important, than what is said. High context cultures are very often collectivistic.

Low context cultures on the other hand are those in which people do NOT presume that others share their beliefs, values, and behaviors so they tend to be more verbally informative and direct in their communication (Hall & Hall, 1987). The message itself is everything. A well-structured argument with a flawless delivery is convincing. Relationships are separated from messages, so the focus is on the details and logic. The clock matters in timing. Many low context cultures are individualistic, so people openly express their views, and tend to make important information obvious to others. Examples are no fear in discussing conflict or talking to strangers.

Direct and Indirect

Direct and indirect styles are closely related to high and low context communication, but not exactly the same. Context refers to the assumption that speakers are homogeneous enough to share or implicitly understand the meanings associated with contexts. Whereas, direct and indirect refers directly to verbal strategies.

Direct styles are those in which verbal messages reveal the speaker’s true intentions, needs, wants, and desires. The focus is on accomplishing a task. The message is clear, and to the point without hidden intentions or implied meanings. The communication tends to be impersonal. Conflict is discussed openly, and people say what they think. In the United States, business correspondence is expected to be short and to the point. “What can I do for you?” is a common question when a businessperson receives a call from a stranger; it is an accepted way of asking the caller to state his or her business.

Indirect styles are those in which communication is often designed to hide or minimize the speaker’s true intentions, needs, wants, and desires. Communication tends to be personal and focuses on the relationship between the speakers. The language may be subtle, and the speaker may be looking for a “softer” way to communicate that there is a problem by providing many contextual cues. A hidden meaning may be embedded into the message because harmony and “saving face” are more important than truth and confrontation. In indirect cultures, such as those in Latin America, business conversations may start with discussions of the weather, or family, or topics other than business as the partners gain a sense of each other, long before the topic of business is raised.

Elaborate and Understated

Elaborate and Understated communication styles refer to the quantity of talk that a culture values and is related to attitudes towards speech and silence. Elaborate styles of communication refers to the use of rich and expressive language in everyday conversation. The French, Latin Americans, Africans, and Arabs tend to use exaggerated communication because in their cultures, simple statements may be interpreted to mean the exact opposite.

Understated communication styles value simple understatement, simple assertions, and silence. People who speak sparingly tend to be trusted more than people who speak a lot. Prudent word choice allows an individual to be socially discreet, gain social acceptance, and avoid social penalty. In Japan, the pleasure of a conversation lies “not in discussion (a logical game), but in emotional exchange” (Nakane, 1970) with the purpose of social harmony (Barnlund, 1975).

Lesser Known Styles

The three styles listed above are researched and discussed most often in intercultural literature, but there are other styles that are equally valid in explaining cultural differences in verbal communication and language usage. Many of these styles are strongly tied to perceptions of logic, power distance, and self.

Although in the United States we often refer to individual words as concrete and abstract, cultural communication styles can be as well. Concrete communication stresses that issues are best understood through stories, metaphors, allegories, and examples with an emphasis on the specific rather than the general. Abstract communication stresses that issues are best understood through theories, principles, and data, with emphasis on the general rather than the specific.

Like concrete and abstract, linear, and circular styles refer to the logical development of a conversation. Linear communication is conducted in a straight line, developing causal connections among subpoints to an explicitly stated end point. There is little reliance on context. Circular communication is conducted in a circular movement, developing context around the main point, which is often left unstated. There is a high reliance on context.

Directly tied to the idea of power distance is the idea of whether verbal communication should be formal or informal. Formal styles are role-centered and emphasize formality with a large power distance. Informal styles emphasize the importance of a lower power distance with informality, casualness, and suspension of roles.

The last style is focused upon the function and value of an individual within a group. A communication style that focuses on the promotion of one’s own accomplishments and abilities is called self-enhancement, where as a style that focuses on the importance of humbling oneself through verbal restraint, hesitation, modesty, and self-depreciation is called self-effacement.

4.4 – Context Rules of Communication Styles

While there are differences in the preferred communication styles used by various cultures, it is important to remember that no particular culture will use the same communication style in all situations all of the time. When a person either emphasizes or minimizes the differences between themselves and the other person in conversation, it is called code-switching. In other words, it’s the practice of shifting the language that you use to better express yourself in conversations.

There are many reasons why people may incorporate code-switching in their conversations. People, consciously and unconsciously, code-switch to better reflect the speech of those around them, such as picking up a southern accent when vacationing in the American South. Sometimes people code-switch to ingratiate themselves to others. What teenager hasn’t used the formal language of their parents when asking for a favor like borrowing the car or asking for money? Code-switching can also be used to express solidarity, gratitude, group identity, compliance gaining, or even to maintain the exact meaning of a word in a language that is not their own.

What does this mean for intercultural communicators? You will try to adapt to other people’s communication preferences (Bianconi, 2002). You notice how long people take when speaking, how quickly or slowly they speak, how direct or indirect they are, and how much they appear to want to talk compared to you. You may also need to learn and practice cultural norms for nonverbal behaviors, including eye contact, power distance, and touch. Please use caution to avoid inappropriate imitation though. Mimicking can be considered disrespectful in some cultural contexts, whereas an honest desire to learn is usually interpreted positively.

4.5 – Translation and Interpretation

Because no one can learn every language, we rely on both human and artificially intelligent translators and interpreters. On the surface translation and interpretation seem to be much the same thing, with one skill relying on written texts and the other orally. Both translation and interpretation enable communication across language boundaries from source to target. Both need deep cultural and linguistic understanding along with expert knowledge of the subject area plus the ability to communicate clearly. In spite of the similarities, translation and interpretation are not the same.

Translation generally involves the process of producing a written text that refers to something written in another language. Traditionally, the translator would read the source in its original language, decipher its meaning, then write, rewrite, and proofread the content in the target language to ensure the original meaning, style and content are preserved. Translators are often experts in their fields of knowledge as well as linguists fluent in two or more languages with excellent written communication skills.

Interpretation is the process of orally expressing what is said or written in another language. Contrary to popular belief, interpretation isn’t a word-for-word translation of a spoken message. If it was, it wouldn’t make sense to the target audience. Interpreters need to transpose the source language within the given context, preserving its original meaning, but rephrasing idioms, colloquialisms, and other culturally-specific references in ways that the target audience can understand. They may have to do this in a simultaneous manner to the original speaker or by speaking only during the breaks provided by the original speaker. Interpreters are also often experts in fields of knowledge, cultures, and languages with excellent memories.

The roles of translators and interpreters are very complex. Not everyone who has levels of fluency in two languages makes a good translator or interpreter. Complex relationships between people, intercultural situations, and intercultural contexts involve more than just language fluency, but rather culture fluency as well.

Learn a little more…

Language management within structural culture frameworks is going on all the time. Language policy is deeply embedded in the beliefs that people have about language and culture. Often language policy centers around who has the ability or authority to make choices where language is concerned, and whose choices will ultimately prevail. Language policy values often manifests in official governmental recognition of a language, how language is used in official capacities, or to protect the rights of how groups use and maintain languages.

While some nations have one or more official language, the United States does not have an official legal language. English is only the de facto national language. Much debate has been raised about the issue, and twenty-seven states have passed “Official English” laws (USConstitution.net, 2/19). Remember linguist and former US Senator S.I. Hayakawa mentioned at the beginning of the chapter? He tried to introduce legislation to adopt English as the official language of the United States several times and failed.

The European Union has 23 official languages and recognized an additional 60 indigenous languages. Canada has two official languages and recognizes an additional 70 indigenous languages from 12 language families. The official language of China is Mandarin or Putonghua, and it recognizes an additional 7 language families with over 300 dialects.

Surprised? Language policies are not just about culture. Language policies are connected to the politics of class, ethnicity, economics, and power as well as culture.

4.6 – Conclusion

It has been said that all language is powerful, and all power is rooted in language (Russell, 1938). Those who speak the same language not only can make themselves understood to one another, but also have a feeling of belonging together. The culture forming power of language and the language forming power of culture is incredibly significant in our understanding of intercultural communication.

Key Terms

- Linguistics

- Denotative

- Connotative

- Constitutive

- Regulative

- Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

- Linguistic Determinism

- Linguistic Relativism

- Cliché

- Jargon

- Slang

- High/Low Context

- Direct/Indirect

- Elaborate/Understated

- Concrete/Abstract

- Linear/Circular

- Informal/Formal

- Self-Enhancement/Self-

- Effacement

- Translators

- Interpreters

Reflection Questions

- Is it possible for two people to communicate effectively if they don’t speak the same language? Should everyone learn a second language?

- What are some cross-cultural variations in language use and communication style? What is the relationship between the language you speak and the way you perceive reality?

- What is your communication style? Are you a high-context or low-context communicator? What are your cultural rules concerning silence and public forms of speech?

- What are some of the functions or ways we use language? Why do people have such strong reactions to language policies, as in the “English only” movement?

- What does a translator or an interpreter need to know to be effective? What is the difference between translation and interpretation? Can you think of any examples to explain the differences?

The study of specific languages and the general properties common to most languages.

The study of the production, acoustics, and hearing speech sounds.

The patterning of sounds.

The patterning of words.

The structure of sentences.

Meaning

Language in context.

The meaning of words often found in the dictionary.

Meaning is often not found in the dictionary but in the minds of the users themselves.

Govern the meaning of words, and dictate which words represent which objects.

Govern how we arrange words into sentences and how we exchange words in verbal conversations.

The structure of a language determines a native speaker’s perception and categorization of experience.

Language and its structures limit and determine human knowledge or thought.

Language is ever changing and growing, in many ways determines reality.

A word or phrase that has lost impact through overuse.

An occupation-specific language used by people in a particular profession.

The use of existing or newly invented words in particular groups.

Cultures in which people assume that others within their culture will share their viewpoints and thus understand situations or nonverbals in much the same way.

Cultures in which people do NOT presume that others share their beliefs, values, and behaviors so they tend to be more verbally informative and direct in their communication.

Refers directly to verbal strategies of speaking directly or indirectly communicating.

Verbal messages reveal the speaker’s true intentions, needs, wants, and desires.

Communication is often designed to hide or minimize the speaker’s true intentions, needs, wants, and desires.

Quantity of talk that a culture values and is related to attitudes towards speech and silence.

The use of rich and expressive language in everyday conversation.

Value simple understatement, simple assertions, and silence.

Stresses that issues are best understood through stories, metaphors, allegories, and examples with an emphasis on the specific rather than the general.

Stresses that issues are best understood through theories, principles, and data, with emphasis on the general rather than the specific.

Resembling a straight line.

Communication is conducted in a circular movement, developing context around the main point, which is often left unstated.

Emphasize the importance of a lower power distance with informality, casualness, and suspension of roles.

Communication style that focuses on the promotion of one’s own accomplishments and abilities.

Style that focuses on the importance of humbling oneself through verbal restraint, hesitation, modesty, and self-depreciation.

The practice of shifting the language that you use to better express yourself in conversations.

Involves the process of producing a written text that refers to something written in another language.

Experts in their fields of knowledge as well as linguists fluent in two or more languages with excellent written communication skills.

The process of orally expressing what is said or written in another language.

Experts in fields of knowledge, cultures, and languages with excellent memories.