Chapter 1 – The Study of Intercultural Communication

Learning Outcomes

When you have completed this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- List and describe the six imperatives.

- Identify which imperative is most closely related to your reason for studying intercultural communication.

- Understand how communication meets various needs.

- Have a working knowledge of the linear, interactional, and transactional models of the communication process.

- Be able to explain how various contexts might impact communication.

What is your reason for studying intercultural communication? Maybe it was a requirement on the road to achieving your major, and you dutifully signed up without having given it much thought. Maybe you’ve spent time overseas or enjoyed spending time with an exchange student at your high school or in your community. Maybe a friend found the class surprisingly interesting and suggested that you take it. Possibly, it was the only class that worked in your limited schedule so you are giving it a try. Whatever your personal reasons—welcome!

Even if you have never taken a communication studies class before, you have a lifetime of experience communicating, and this experiential knowledge provides a useful foundation from which you can build upon. This book is designed to help us to take a look at what we already know by applying principles that will guide our understanding of intercultural communication competence.

1.1 – The Six Imperatives or Reasons Why We Study Intercultural Communication

When considering the various reasons for studying intercultural communication, most answers will fall into what scholars Martin & Nakayama (2011) call the six imperatives or reasons for studying intercultural communication. The six imperative categories are:

- Peace

- Demographic

- Economic

- Technology

- Self-awareness

- Ethics

Let’s take a quick look at each imperative individually.

The Peace Imperative

History is full of conflict. Contemporary life is full of conflict. Conflict over politics, religion, human rights, climate change, wealth, medical care, plus food, water, and mineral resources are often in the news. It would be naïve to assume that simply understanding intercultural communication principles would end conflict, but there is a need for all of us to learn more about cultural groups other than our own if we wish to be competent communicators. The peace imperative begs the question as to whether individuals of different races, ethnicities, languages, and cultures can exist together on this planet? If so, what does that look like? If not, what does that mean?

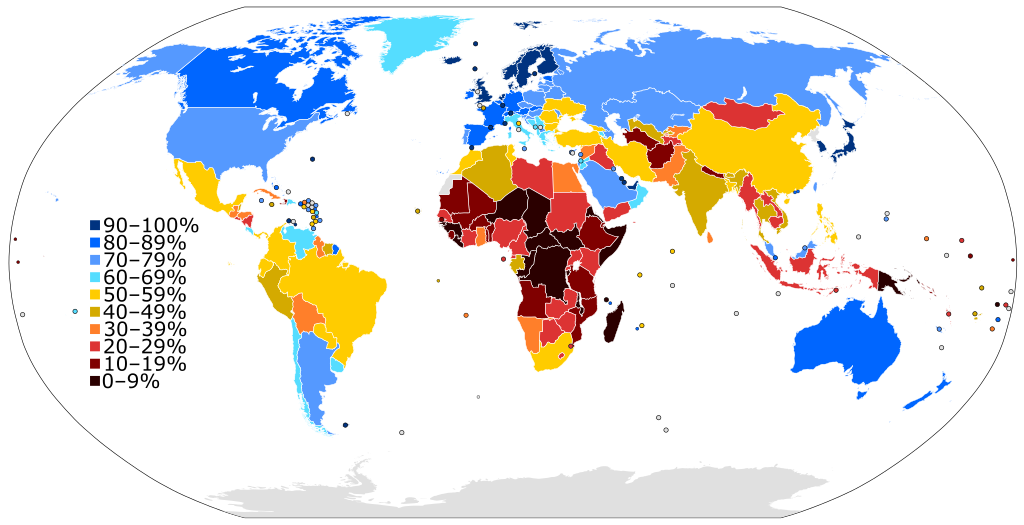

The Demographic Imperative

Demographics are the characteristics of a population such as gender, age, race, ethnicity, economic status, educational status, and more. Demographics are generally those traits and characteristics that we can count. U.S. demographics, as well as those around the rest of the world, are changing quickly and dramatically. Migratory populations escaping from climate and economic issues are crossing borders in record numbers. Borders are becoming more fluid as countries go on land grabs in neighboring territory. Pandemics don’t recognize borders at all. The demographic imperative is not only about immigration though, it’s also about change. As demographics change, culture changes.

Vocabulary that describes groups of people and are associated with the demographic imperative include the terms, heterogeneous, homogeneous, diversity, and nativistic. If a population is considered heterogeneous, there are differences in the group, culture, or population. If a population is considered homogeneous, there are similarities in the group, culture, or population. Diversity is the quality of being different. A nativistic group is extremely patriotic to the point of being anti-immigrant.

The Economic Imperative

To compete and be effective in the global market, an accurate understanding of the economies and ways of doing business around the world is crucial. The interdependence of our world market in consumer goods, services, labor, and capital has been dramatically illustrated by the shortages produced by the COVID pandemic. Formerly efficient supply chains were disrupted. Economically affordable products became expensive for lack of local sources. Labor shortages around the world impacted everyone on the planet. The economic imperative is reflected by the impact that business globalization has on the average person.

The Technology Imperative

Technology has made communication easier than ever before. Information has become so easy to access and manipulate that we are now confronted with the impact of fake news and purposeful disinformation along with the closely related economic issue of the digital divide. The digital divide refers to people who grew up with access to technology versus those who did not have access to technology and did not develop the associated skills. Digital natives, or people who grew up using technology, are often citizens of wealthy nations that live lives of comparable privilege and often have better economic prospects. Technology is also used as an identity management tool and will be discussed as such in a later chapter.

The Ethical Imperative

Does the idea of a digital divide challenge your sense of social justice? If so, you are concerned with the ethical principles of conduct that help govern the behaviors of individuals and groups. Generally, there are two basic ways that humans apply ethical values to behavior—universally or relatively. If you are viewing a behavior as a relativist, you believe that no behavior is inherently right or wrong, rather everything depends on perspective. In other words, you might not make the same choice yourself, but are willing to understand why others would make that choice. If you are viewing a behavior as a universalist, you believe that cultural differences are only superficial, and that fundamental notions of right and wrong are universal. In other words, everyone should be making the same choices for the same reasons.

Although universalism and relativism are thought of as an either/or choice, realistically most people are a combination of both views. There are some issues you might hold strict opinion about while other issues you are willing to be more open about.

The Self Awareness Imperative

One of the most important reasons for studying intercultural communication is the awareness it raises of our own cultural identity and background. The self-awareness imperative helps us to gain insights into our own culture along with our own intercultural experiences. All cultures are ethnocentric by their very natures. Ethnocentrism is a tendency to think that our own culture is superior to other cultures. Most of us don’t even realize that we think this way, but we do. Sure, we might admit that our culture isn’t perfect, yet we still think that we are doing better than everyone else. Ethnocentrism can lead to stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. These ideas will be discussed in greater detail later in the book.

Learn A Little More!

Ever since I was very young—even before I could find it on a map—I have wanted to go to the People’s Republic of China. For much of my lifetime, China was almost impossible to visit. There were no direct flights available. Invitations had to be issued from work units in the PRC. Various permissions and permits had to be arranged before entry. Special money called foreign exchange currency (FEC) was required for use. Upon return to your home country, many travelers were requested to describe their trip in great detail to their family and friends as well as various governmental agencies who were also interested in the PRC. It was quite an adventure!

For a long time, I thought that my interest in the PRC was based on the exotic and restricted nature of the location, but it turned out that wasn’t. It was Bennett. Bennett’s family was from the old Canton (now Guangzhou). Because of famine, political unrest, and civil war, they made their way to Hong Kong which was a leased British colony at the time. As a lone young man, Bennett immigrated first to Canada, and then to the United States. He worked with my father as a chemist in the Midwest for many years spending most weekends and holidays with my extended family. To my young ears, his thickly accented stories weren’t that much different than my grandparents thickly accented stories. Histories, stories of adversity, and fairy tales are commonly shared at family gatherings.

Eventually, Bennett married Pat, started a family, and moved to another part of the Midwest. Slowly visits became yearly holiday cards and then we lost touch as Bennett faded from my conscious memory. Unconsciously, my early contact with Bennett fueled a lifelong desire to visit and learn more about the civilization that produced someone who was once so important to me.

So, what’s your story? Why are you taking intercultural communication? What do you already know about this topic that could help guide your learning?

1.2 – Communication Principles and Processes

The imperatives help us to organize our personal reasons for studying intercultural communication, but what about the communication process in general? Most of us think that “communication” is important, but it’s not something that we are often focusing on so we have a tendency to think that it “just happens.” Consciously becoming aware of the communication process and noticing how you communicate is a fundamental goal of this class. Studying the communication process will allow you to understand more of what is going on around you, and this understanding will allow you to become a more competent communicator in intercultural contexts.

If you have taken another communication class, the following sections will be a review of what you have learned previously. If you have never taken a communication class, the following sections are foundational to understanding the basic communication principles and processes so pay close attention. Everything that we learn in this class will be grounded in these principles and processes.

Communication Principles

In this section, we will learn the principles of communication. You are encouraged to note the aspects of communication that you haven’t thought about before and begin to identify the principles in the various parts of your communication life.

Communication Meets Needs

Communication is far more than the transmission of information. The exchange of information is important for many reasons, but it is not enough to meet the various needs we have as human beings. The content or message of our communication may help us meet certain physical, instrumental, relational, and identity needs.

Physical needs include needs that keeps our bodies and minds functioning like air, food, water, and sleep. Instrumental needs include needs that help us get things done in our day-to-day lives and achieve short- and long-term goals. Relational needs include needs that help us maintain social bonds and interpersonal relationships. Identity needs include our need to present ourselves to others and be thought of in desired ways.

Communication Is A Process

Communication can be defined as the process of understanding and sharing meaning (Pearson & Nelson, 2000). When we refer to communication as a process, we imply that it doesn’t have a distinct beginning and end or follow a predetermined sequence of events. It can be difficult to trace the origin of a communication encounter, since communication doesn’t always follow a neat format.

Communication Is Influenced by Culture and Context

Culture and context influence how we perceive and define communication. Cultural values are embedded in how we communicate. All people in all cultures are socialized from birth to communicate in culturally specific ways that vary from context to context.

Communication Is Learned

Most of us are both capable of the capacity and ability to communicate, but we all communicate differently. This is because communication is learned rather than innate. As already discussed in the previous principle, communication patterns are relative to the context and culture in which one is communicating. We are all socialized into different languages, but we also speak different “languages” based on the situations we are in. This idea will become more understandable in the verbal and nonverbal communication chapters.

Communication Influences Your Thinking About Yourself And Others

Humans share a fundamental drive to communicate. You share meaning in what you say and how you say it. On the flip side, your communication skills also help you to understand others—not just their words, but also their tone of voice, their nonverbal gestures. Your success as a communicator is based on your ability to actively listen and actively interpret others’ messages.

The Communication Process

Communication is a complex process, and it is difficult to determine where or with whom a communication encounter starts and ends. Models of communication simplify the process by providing a visual representation of the various aspects of a communication encounter. Models allow us to see specific concepts and steps within the process of communication. Although the three models differ, they all contain some common elements such as senders/receivers, messages, encoding, decoding, and channels. Other elements to remember include feedback and noise.

In all the communication models, the participants are referred to as senders and receivers. Senders initiate the message conveyed through the communication process and receivers are the recipients of the message. The message is the verbal or nonverbal content being conveyed from sender to receiver.

The internal cognitive processes that allow participants to send, receive, and understand messages are known as the encoding and decoding processes. Encoding is the process of turning thoughts into communication. Decoding is the process of turning communication into thoughts. For example, you may realize you are hungry and encode the following message to send to your roommate: “I’m hungry. Do you want to get pizza tonight?” As your roommate receives the message, they decode the message you are expressing and turns it back into thoughts in order to make meaning out of it. Of course, we just don’t communicate verbally—we have various options, or channels for communication.

Encoded messages are sent through a channel, or a sensory route on which a message travels, to the receiver for decoding. Communication can be sent and received using any sensory route (sight, smell, touch, taste, or sound). Nor does communication have to be sent using only one route—it can be multi-channeled.

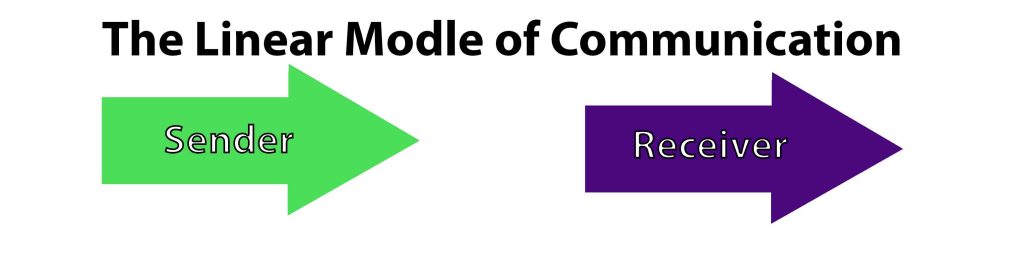

The Linear Model of Communication

The linear model of communication describes communication as a linear, one-way process in which a sender intentionally transmits a message to a receiver (Ellis & McClintock, 1990). Although the receiver is included in the model, this role is viewed as more of a target or end point rather than a part of an ongoing process. The receiver either successfully receives and understands the message or they do not.

An example of a linear message is listening to the radio in your car. The sender is the radio announcer (the sender) encodes a verbal message that is transmitted by a radio tower (the channel) and eventually reaches your ears (the receiver) via the speakers in order to be decoded. The radio announcer doesn’t really know if you receive their message or not, but if everything is working as it should be, there is a good chance that the message has been received.

Most communication situations are more complex than the linear model, but the linear model is always a good place to start as you begin to dissect a communication situation for greater understanding.

The Interactional Model of Communication

The interactional model of communication describes communication as a process in which participants alternate positions as sender and receiver and generate meaning by sending messages and receiving feedback within physical and psychological contexts (Schramm et al., 1997). Rather than illustrating communication as a linear, one-way process, the interactional model incorporates feedback, which makes communication a more interactive, two-way process. Feedback includes messages sent in response to other messages. The inclusion of a feedback loop also leads to a more complex understanding of the roles of participants in a communication event.

The interactional model is focused on both the message and the interaction. While the linear model is focused on transmitting a message, the interactional model is more concerned with the communication loop itself. Feedback and context help make the interactional model a more accurate illustration of the typical communication process.

The Transactional Model of Communication

Currently, many scholars view communication as more than a process that is used to carry on conversations and convey meaning. People don’t send messages like computers, and they don’t neatly alternate between roles of sender and receiver as the communication event unfolds. People also can’t decide to stop communicating, because communication is more than verbally sending and receiving messages.

The transactional model of communication describes communication as a process in which communicators don’t just communicate to exchange messages—people communicate to create relationships, form intercultural alliances, shape self-concepts, and engage with others to create community. In other words, people don’t communicate about their reality, communication helps to construct the reality.

The roles of sender and receiver in the transactional model differ significantly from the other models. Instead of being the sender or the receiver, people are both senders and receivers at the same time. Communicators are simultaneously sending messages and receiving messages adapting the message being sent as we are receiving messages from others. Communication is a force that shapes our realities–before and after—communication events, therefore social, relational, cultural and physical contexts frame and influence our social encounters. Context refers to the factors that work together to determine the meaning in communication events. In other words, we learn the norms and rules for communicating through the process of communicating. The norms and rules are different based upon the types of relationships we have, and the cultural expectations of the communicators.

Like the idea of context in the communication process, noise refers to things that influence or block the effectiveness of interpretating communication. Noise can be caused by various things ranging from illness and faulty cell phone reception to stereotyping and poor grammar. While often overlooked as having an impact on the communication process, noise can subtly impact competent communication by acting as a disruption to the message/channel as well as within senders/receivers.

1.3 – Conclusion

We live in a rapidly changing world with larger forces driving us to interact with others who are culturally different from ourselves. There are six major categories of imperatives that reflect our reasons for wanting to study intercultural communication. These imperatives are peace, demographics, economic, technology, ethical and self-awareness. Regardless of which imperative is personally most important to an individual, one fact is important to remember: the communication choices we make determine the personal or national or international outcomes that follow.

Understanding that communication is a linear, interactional, or transactional process rather than something that “just happens” helps communicators “see” more of what is going on around them. Whether you are a sender or receiver or both at the same time, communication is far more than just transmitting information. There are social, relational, cultural, and physical contexts that frame our communication norms and rules. This class will encourage you to look for and take note of the contexts and communication processes that you haven’t been aware of before.

The opposite of ethnocentrism is self-reflexivity or the process of learning to understand oneself and one’s position in society. Learning about others helps us to understand ourselves. Cultures are made up of people attempting to make good decisions about how to live a life. Like you, they have values and beliefs that govern their choices. Analyzing the communication of people who are different than you can lead to a whole new appreciation of the diversity of humankind. Maybe this idea is new to you, but the study of intercultural communication is actually the study of YOUR story within the human story.

Key Terms

- Peace Imperative

- Technological Imperative

- Heterogeneous

- Nativistic

- Relativist

- Communication Principles

- Message

- Channel

- Linear Model

- Self-Reflexivity

- Demographic Imperative

- Ethical Imperative

- Homogeneous

- Digital Divide

- Universalist

- Sender

- Encoding

- Feedback

- Interactional Model

- Economic Imperative

- Self-Awareness Imperative

- Diversity

- Digital Natives

- Ethnocentrism

- Receiver

- Decoding

- Context

- Transactional Model

Reflection Questions

- The book shares six reasons—or imperatives—for studying intercultural communication. Choose the reason/imperative that most closely reflects your own reason(s) for studying intercultural communication and write two or three paragraphs that explains your motivation for being in this class.

- Consider an instance in which you didn’t intend to communicate a message, but someone saw your behavior as communication. How did this person misinterpret your behavior? What were the consequences? What did you say and/or do to correct the misperception?

- Recall an interaction that took a sudden turn for the worse. How did each person’s communication contribute to the change? What are some of the variables that effect meaning? What did you say or do to deal with the situation?

- Is communication intentional or unintentional? Can I send messages that I don’t mean to send? How can I tell if someone receives a message that I didn’t mean to send? Can I have a whole conversation without understanding the “mixed” message? Does it matter?

- What is competent intercultural communication? What is the difference between competent intercultural communication and effective intercultural communication? Can I be effective and not competent? Explore this. Give a personal or historical example.

Reasons for studying intercultural communication (peace, demographic, economic, technology, self-awareness, ethics).

The possibility of different races, ethnicities, languages, and cultures existing together.

Changes coming from changing demographics and/or changing immigration patterns.

Differences within the group, culture, or population.

There are similarities within the group, culture, or population.

Quality of being different.

A group that is extremely patriotic to the point of being anti-immigrant.

Reflected by the impact that business globalization has on the average person.

Refers to people who grew up with access to technology versus those who did not have access to technology and did not develop the associated skills.

People who grew up using technology.

You believe that no behavior is inherently right or wrong, rather everything depends on perspective.

You believe that cultural differences are only superficial, and that fundamental notions of right and wrong are universal.

Helps us to gain insights into our own culture along with our own intercultural experiences.

Tendency to think that our own culture is superior to other cultures.

Initiate the message conveyed through the communication process.

The recipients of the message.

The verbal or nonverbal content being conveyed from sender to receiver.

The process of turning thoughts into communication.

The process of turning communication into thoughts.

A sensory route on which a message travels to the receiver for decoding.

Describes communication as a linear, one-way process in which a sender intentionally transmits a message to a receiver.

Describes communication as a process in which participants alternate positions as sender and receiver and generate meaning by sending messages and receiving feedback within physical and psychological contexts.

Includes messages sent in response to other messages.

Describes communication as a process in which communicators don’t just communicate to exchange messages—people communicate to create relationships, form intercultural alliances, shape self-concepts, and engage with others to create community.

The factors that work together to determine the meaning in communication events.

Refers to things that influence or block the effectiveness of interpreting communication.

The process of learning to understand oneself and one’s position in society.