Chapter 11 – Education

Learning Outcomes

When you have completed this chapter you should be able to do the following:

-

Understand the role of culture in education and education in culture.

- Understand the expectations that different cultural groups have about education.

- Explain how different role expectations can influence communication within the educational context.

- Explain how power differences can influence communication within the educational context.

- Identify your preferred teaching and learning styles.

The idea of educating people has been around since the beginnings of human history. The first documented word used to describe the idea of an “education” originated in the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Ages whereas the modern English word, “education,” is a combination of two Latin words from the mid-1500s. These Latin words roughly translate in meaning as “to bring up” and “lead forth.” The goal of most modern education systems still reflects the Latin roots of the English word because modern education systems make students familiar with many things so that they can lead their societies forward. Culture and education are closely intertwined.

All cultures have some form of an education system, but it is no means universal. The features of any given system can vary widely from culture-to-culture. Common variations include the formality or informality of the system, the emphasis on memorization or experiential knowledge, general education versus specific occupational education, and whether the educational system is open to all or a select few. How cultures deal with these issues can have a profound effect on how individuals see the world and process information.

11.1 – The Impact of Education on Culture

Just as a culture influences education, in the same way education also influences the culture of a country. There are four basic ways that education influences a culture.

- First, education preserves a culture. Each country has a distinct culture and education is the most common means through which this task can be accomplished.

- Second, education transmits culture. The process of preservation includes the process of transmission from one generation to another.

- Third, education develops culture. The function of education is to bring needed and desirable change for progress and continued development of a culture. Education has the potential to modify cultural processes as they become outdated.

- And fourth, education upholds the continuity of culture. Cultural values, beliefs, and behaviors are established and reinforced in a school’s curriculum.

Education reflects the social, cultural, and political conditions prevailing outside of school, but it also has the seeds of change and can keep up with the ever changing world. School is both a place of knowledge, and a society in miniature.

11.2 – The Impact of Culture on Education

All educational systems strive to produce effective citizens capable of participating in, and contributing to, their societies. Education is not simply driven by the simple desire to teach and learn. Education is enculturation. Enculturation is the process by which people acquire the values, norms, and worldviews of their cultural group. An example of enculturation could be watching family members go grocery shopping. You learn which stores you typically go to, which foods you usually eat, how to pick good products, and what foods are used to make your favorite dishes.

Acculturation is the process where people from one culture adopt the process of another culture which is not their own. Acculturation begins when two cultures meet. Acculturation is not necessary for survival but is basically adopted because the dominant culture has influence over the other. Acculturation is often seen in those far from their home cultures such as refugees and migrants but can also apply to co-cultural and microcultural groups within a dominant culture as well.

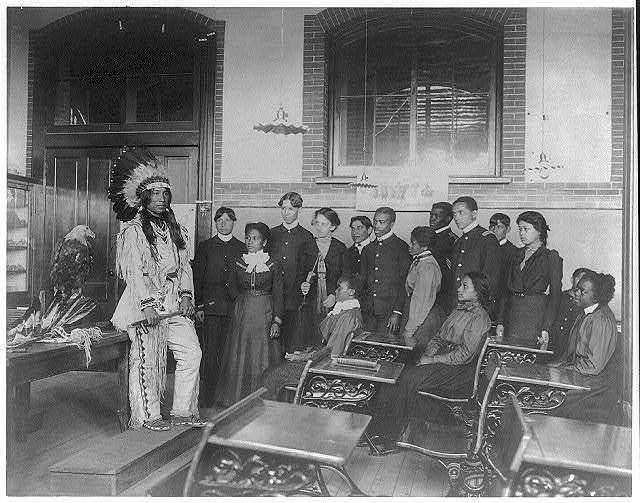

There is no universal curriculum that all students in all cultures follow. History plays an important role in student experiences of education as well as the educational systems created within a culture. During the era of great national expansion known as the colonial period, the colonizers educational systems were imported into the conquered or assimilated nations. Western-style education systems, originally under the auspices of the colonial education system, can be controversial even today. Colonial education systems—rightly or wrongly–have been accused of being tools by capitalists to exploit the underdeveloped world to keep people in subjection (Basu, 1989).

Whether a culture has a colonial educational history or not, currently education is widely perceived to be an important avenue for advancement within a society. In an era when it is estimated that a weeks’ worth of the New York Times contains more information than a person was likely to come across in a lifetime in the 18th century, most cultures place high value on their education systems (Scott, ret. 8/4/19).

11.3 – Cultural Dimensions and Education

All education systems strive to produce effective citizens that can participate in and contribute to their societies. Because of the nature of cultural values and beliefs, how this is achieved can look very different from culture to culture. Educational philosophies, administration, and practices reflect not only the cultural dimensions, but, religious, political and/or economic stability as well. Even though teachers and students may be oblivious to their origins, Confucian, Judeo-Christian, Islamic, and other religious principles clearly permeate the world view and philosophical systems of cultural values. Countries plagued by chaos within political and economic systems do not usually have enough resources to develop consistent, effective educational systems to serve their citizens.

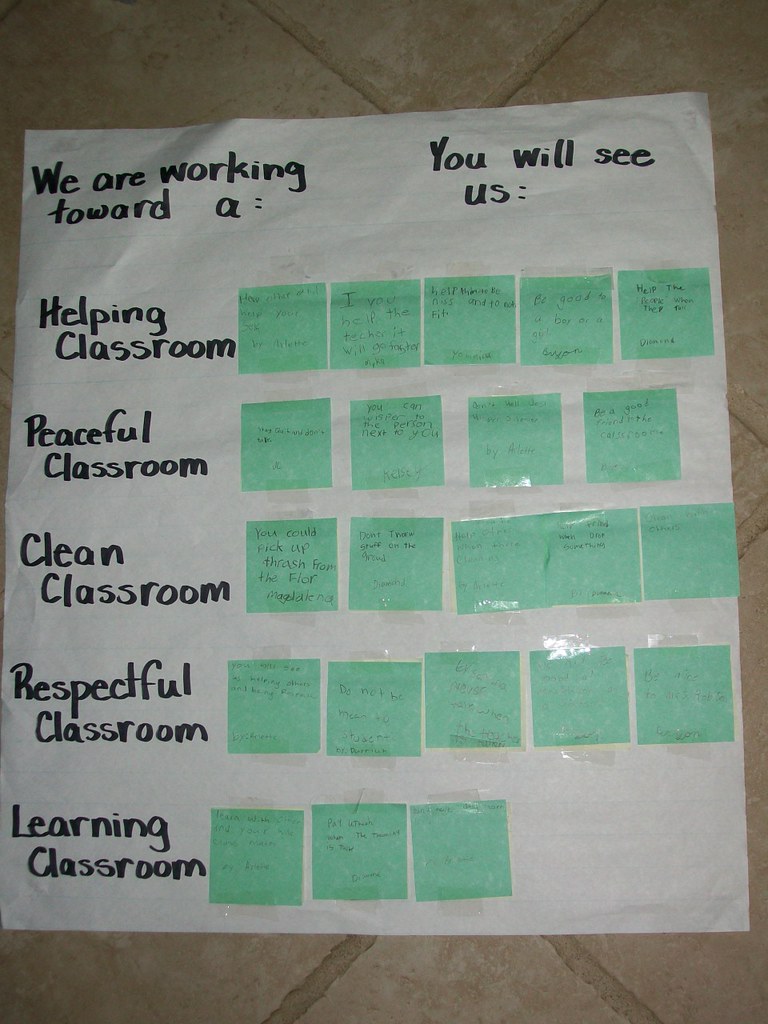

Individualism and Collectivism

Underlying the many differences between cultures, and the educational systems that have emerged from them, is individualism and collectivism. Collectivism is marked by structured relationships where individual needs are subservient to the group. Solidarity, harmony, and equal distribution of rewards among students is expected. Modesty is valued, norms are set by the average student, and failure is seen as unfortunate but not dire. Success is seen as something linked to family, classmates, and society as a whole (Rubenstein, 2001; Dimmick & Walker, 2005; Watkins, 2000).

Conversely, individualism is marked by loose relationships and ties that are forged according to self-interest. Status and grades are based on individual success. Competition is encouraged, norms are set by the best students, and failure is perceived as fairly significant (Rubenstein, 2001; Dimmick & Walker, 2005; Watkins, 2000).

These basic values impact everything from the atmosphere in the classroom, teaching styles, and attitudes about dishonesty and plagiarism. In collectivistic classrooms, for instance, education is seen as a tool for strengthening the country rather than for the betterment of an individual. This fundamental premise has implications for the teacher-student relationship in that working together is not cheating, but rather a happy by-product of good relations. The collectivistic mentality may also account for the absence of sorting students by ability, and the lack of teasing of less gifted students. Fast learners are expected to help slow learners (Rubenstein, 2001).

In individualistic classrooms, education is seen as a tool for getting ahead. Students are responsible for their own learning. Academic progress is measured through individual assessment and reported as individual grades. The learning relationship is primarily between the teacher and the student, not the classmate group. If a student needs help, they ask the teacher questions. Students are taught to be more engaged in discussions and arguments. Schools encourage students to become independent thinkers (Faitar, 2006)). An academic task has value in and of itself so getting one’s work done is important. Relationships with other students is secondary. In certain situations, helping others could be cheating (Rosenberg, Westling, & McLeskey, 2010).

Even concepts of intelligence are culture-based. Individualistic cultures tend to think of intelligence as a “gift” and relatively fixed, although somewhat impacted by environmental influences. Collectivistic cultures view intelligence as something that can be improved by hard work rather than a lack of ability (Henderson, 1990; Watkins, 2000).

Power Distance

Reflections of power distance can show up in education systems as well. High power distance classrooms focus on expertise, authority along with the importance of social and moral order. Leaders have stronger social prominence, and there are explicit, enforced barriers to information. Examples of this can be libraries and information structures only available to certain majors or even specific faculty. Degrees with official stamps and logos might only be issued to select graduates and not others.

In lower power distance classrooms, students are required to take much more responsibility for their own actions and learning. The institution respects the independence of the students and student driven initiatives. Students are expected to find their own way. Restrictions to learning are discouraged, and that sometimes includes letting students know that they do not have the skills to succeed in their desired careers path. Instructors are treated as equals to be engaged and even challenged.

Time

As previously discussed, cultures can view time in a variety of ways. The classroom will also reflect the cultural preference for time.

Polychronic and Monochronic

Monochronic classrooms view time as something to be managed so learning proceeds along a linear path with clear prerequisites and milestones. Goal setting is important, so time and opportunities are not to be wasted. Repetition might be seen as a lack of progress. The past might be seen as less significant than the future. Students expect to see immediate relevance to a subject area.

The polychronic classroom adapts to time. Learning is seen as the practice needed to reach perfection, so goals are secondary as one adapts to the situation. Time exists for observation and opportunities can reoccur which makes the past important because cycles repeat themselves. Repetition is valuable for learning therefore students may have to be more patient to discover the relevance of the lesson.

Long-term and Short-term

When instructional activities start and stop promptly according to “clock time,” it is considered a short- term classroom. Meetings outside of class time are limited to schedules and there are procedures to follow when working on assignments. There are consequences for missing deadlines.

Instructional activities that are allowed to continue if they are useful is a trait of a long-term classroom. If there is improvement, there is less adherence to deadlines and procedures can have flexibility. The boundaries between class time and outside of class time is loose.

Uncertainty Avoidance

Uncertainty avoidance can have a major impact on the classroom. High uncertainty avoidance classrooms tend to focus on error prevention so smaller amounts of information is given with choices being limited. Simplicity is used to reduce the ambiguity and students are given the exact assessment rubrics for grading.

The low uncertainty avoidance classroom shows up in the complexity of the assignments. Instructors avoid over protection and maximize rather than minimize choices. There is often an abundance of additional recommended reading, and assignments are designed to produce meaningful learning for students.

Masculine and Feminine

In more feminine classrooms, the average student is used as the norm and teachers often avoid praising students. Rewards are given more for social skills than intelligence and failure is not a life-altering event. Students choose subjects of interest for majors.

In more masculine classrooms, teachers use the best students as the norm by often praising and rewarding them. Failure can be life-altering, and students compete for top positions in a class. Students will choose majors based on their career opportunities.

Different Approaches to Knowing

How do we “know” what we claim to know? Although this is not something that Hofstede has explored as a cultural dimension, the idea of extended epistemology or other ways of developing knowledge (Carter, et. al, 2018) has been gaining traction in educational scholarship in recent years. Scholars generally categorize the different ways of knowing as empiricism, rationalism, authority, and revelation.

Generally speaking, European cultures tend to consider information acquired to cognitive processes such as counting, measuring, and the “scientific process” as more valid than other ways of knowing things. Other cultures might prefer symbolic imagery, rhythm or transcendence. The different approaches to knowing could affect the ways that information and problem-solving is taught and accepted within an educational setting.

11.4 – Practical Applications

Researchers continue to build an in-depth understanding of the customs and practices within certain cultures with the goal of developing meaningful ways to compare cultures. Much of our communication behavior and our expectations for the educational process are deeply embedded parts of our culture. What happens in the classroom is primarily reflective of the values of the dominant culture (Evertson & Randolph, 1995; Hofstede, 1980, 2005).

Numerous studies have been done in a variety of cultures to measure teaching and learning styles. Although there is considerable debate as to whether this field of study is accurate across cultural boundaries or should be more focused on individuals, there is enough reason to believe that differences in cultural socialization tend to influence learning styles. As culture has the ability to shape the ways in which its members receive, process and act on information, it does shape the way cultural members learn.

Teaching Styles

Teachers generally use one of the two types of teaching styles: teacher-centered or student-centered (Prosser & Trigwell, 2010). Encouraging students to become independent thinkers, focusing on individual needs, being assertive and expressing opinions, criticism as a strategy for improvement, and trying to bring about conceptual change in students’ understanding of the world are all considered student-centered strategies (Faitar, 2006). Knowledge that is always transferred from an expert to a learner, with conformity and group needs as a focus, are considered more teacher-centered strategies (Staub & Stern, 2002). Students used to teacher-centered instruction may be puzzled, or even offended, by the more informal student-centered approach. They may perceive the teacher as being poorly prepared or lazy (McGroaty & Scott, 1993).

In individualistic settings, the teacher’s role in the classroom is to share ideas and provide practice time to develop further knowledge and/or skills. In collectivistic settings, the teacher is viewed as a moral guide, and friend or parent figure with valuable knowledge that it is a student’s duty to learn (Husen & Postlethwaite, 1991). Researchers Cortazzi & Jinn (1998) compared British and Chinese student/teacher relationships and noted that in Britain good students obeyed and paid attention to the teacher, but in China, students and teachers assumed that all students would behave in this way. Consequently, Chinese teachers spend little time and effort on discipline. In Norway and Russia, students often spend their first 5 or 6 years of school with the same teacher (Cogan et al., 2001).

Learning Styles

The ways that student learn in different cultures is called learning styles—as is how students communicate. In the US, direct eye contact is interpreted as a sign of interest and honesty. The lack of eye contact is considered a sign of dishonesty or lack of interest, so teachers adjust their styles accordingly. Looking a teacher in the eye in many Asian countries would the height of disrespect.

In some cultures, students are taught using through modeling and observation therefore students might not be familiar with the idea of active listening to understand concepts and instructions. Asking questions might imply that the teacher did not teach well and can be considered impolite or challenging the teacher.

In a few cultures, debating or engaging in discussions with different points of view can also be seen as a challenge. Not only is challenging teachers or authority figures seen as disrespectful, but such tactics might not be seen as a learning strategy and ignored. Lectures are the standard mode of instruction and discussion might not even have a place in the classroom.

Even in cultures where discussions are a standard classroom activity, the unwritten rules for discussion may be very different than in the US (e.g. interruptions, loud talking, allowing for short silence, and being called upon). Students may even smile during an intense discussion because they have been taught to react this way so as not to offend the person in authority.

Group work is also approached differently in different places. Group dynamics are developed in a more systematic and sustained manner with greater interdependence and collaboration. Individual instructors in the US may define what are and are not acceptable forms of collaboration in the context of a particular course, but the rules do not apply to all courses.

In the US, the class is often split into pairs, or small groups to work on a task or to discuss a topic. Watkins calls this “simultaneous pupil talk. In a Chinese classroom, you would more likely view “sequential pupil talk” where two students at a time stand and engage in dialogue while the others listen and think. Students from some countries may think certain forms of collaboration are acceptable which might be considered as “cheating” in the US.

The ideas of testing and evaluation can also vary widely from culture to culture. Students in many countries are accustomed to very rigorous high stakes testing. Multiple choice tests, common in the US, are rare outside of the US.

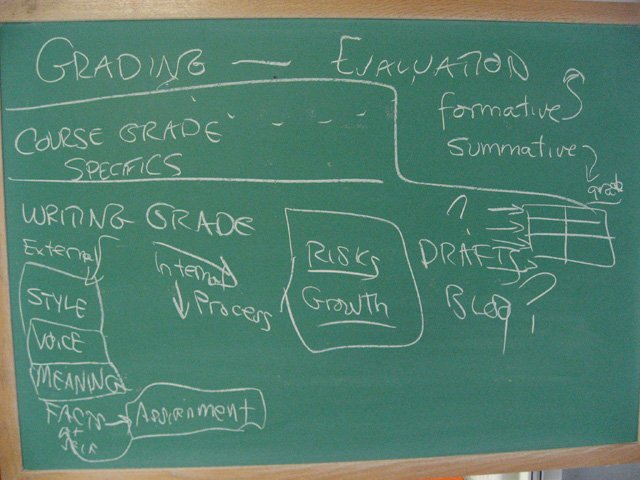

Grading, Power, and Plagiarism

Cultures can have very different expectations about grades and the grading process. There may always be power distance issues in the communication between instructors and students, but these differences will be greater or lesser depending on the culture. Notions of what constitutes being “fair” or “unfair” are cultural embedded as well. Seeking help or soliciting help may not be appropriate or acceptable in some cultures

Attitudes towards cheating and plagiarism, as well as what constitutes each, can be very different. Plagiarism, or the concept that ideas can be owned, is a Western principle. Some cultures require students to memorize and use long passages from well-know experts without crediting them as a matter of education.

In cultures where a strong emphasis is placed on interdependence, “helping” your classmates may be more important than competing with them. “Turning in” a classmate who cheats may be considered a more serious ethical breach than the act of cheating. Maintaining family reputation, keeping a scholarship, or negotiating for grades could be appropriate in some instances.

Grading systems are far from universal, making the understanding of what a grade means opaque at best. In the Chinese University system, grades are often based on one final examination. There are no other grades, so plagiarism is rarely considered a problem. In the Japanese University system, final grades are based on the mid-term and final. There are no regulations about plagiarism in Japan or Nepal. Students do not need to attend classes in the Nepal University system; they can choose to directly sit for the national exam. Attendance and plagiarism are very important in the university system in India, but students can negotiate with their professors for grades. The Iranian university system also enforces consequences for plagiarism but considers gift-giving an opportunity for extra credit (Smith et al., 2013).

In the US, grades are only one of many factors considered in job and school applications. In some parts of the world the grades that you get in preschool will determine whether you will go to college or not.

11.5 – Conclusion

Most people spend many years in school. The education process considered in this chapter explores a common world-wide institution created to preserve, transmit, develop, and uphold culture. The reciprocal nature of “culture” and “education” is significant to all of our childhood experiences, and influences who we will eventually become.

Key Terms

- Education

- Enculturation

- Acculturation

- Colonial Period

- Collectivistic/Individualistic Classrooms

- High/Low Power Distance Classrooms

- Poly/Monchronic Classrooms

- Long/Short-term Classrooms

- High/Low Uncertainty Avoidance Classrooms

- Masculine/Feminine Classrooms

- Teaching Styles

- Student-centered

- Teacher-centered

- Learning Styles

Reflection Questions

- What is the purpose of education? Is education free in your country? Is education compulsory (required)? Do parents homeschool their children in your country? How many years is it considered “normal” for children to go to school?

- What is the role of language in learning and teaching? Do you speak a different language in different settings, such as home, school, or work? Do parents expect and desire assimilation of children to the dominant culture as a result of education and the acquisition of a new language?

- Is it appropriate for learners to ask questions or volunteer information in your country? If so, what behaviors signal these behaviors? If not, what negative attitudes does this behavior cause? What are the skills that separate good students from bad students? What constitutes a “positive” response by a teacher to a learner? By a learner to a teacher? Are there different responses for different groups? Boys? Girls? In different subjects?

- What kinds of learning are favored (e.g. memorization, discussions, inductive, modeling, stories, lectures)? Is it better to learn collaboratively or individually? Should all students be expected to learn everything? Are teachers responsible for student learning or are students responsible for student learning? What about parents? How does how well student learn reflect on parents?

- How important was learning to you? Did you ever cheat? What is your attitude towards cheating? How should parents react? How should teachers react? What are the dangers of cheating? How were students disciplined in your school?

The process by which people acquire the values, norms, and worldviews of their cultural group.

The process where people from one culture adopt the process of another culture which is not their own. Acculturation begins when two cultures meet.

The colonizers educational systems were imported into the conquered or assimilated nations.

Is a social organization in which individuals are seen as subordinate to the group.

Refers to people’s tendency to take care of themselves and value individual accomplishments.

Education is seen as a tool for strengthening the country rather than for the betterment of an individual.

Education is seen as a tool for getting ahead and students are responsible for their own learning.

Focus on expertise, authority along with the importance of social and moral order.

Classrooms that follow the principles of low power distance.

View time as something to be managed so learning proceeds along a linear path with clear prerequisites and milestones.

Learning is seen as the practice needed to reach perfection, so goals are secondary as one adapts to the situation.

When instructional activities start and stop promptly according to “clock time.”

Instructional activities scaffold or build upon one another.

Tend to focus on error prevention so smaller amounts of information is given with choices being limited.

Students are required to take much more responsibility for their own actions and learning.

Other ways of developing knowledge.

The primary strategies adopted by teachers to convey knowledge in a classroom.

Encouraging students to become independent thinkers, focusing on individual needs, being assertive and expressing opinions, criticism as a strategy for improvement, and trying to bring about conceptual change in students’ understanding of the world.

Knowledge that is always transferred from an expert to a learner, with conformity and group needs as a focus.

The different ways that students learn.