Chapter 2 – Starting With Culture

Learning Outcomes

When you have completed this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain how the various components of the definition of culture translate into the communication principles.

- Define what it means to say that culture is “structured” or “transactional.”

- Explain the five questions that every society must answer according to the Values Orientation Theory.

- List and define Hofstede’s Dimensions of Culture.

- Explain the difference between co-cultures and microcultures.

There is a challenge to understanding other human beings because of the immense variations—and similarities–within human societies. Often, we use the term “culture” describe these variations and similarities, which makes the term “culture” itself very difficult to define. Academics have yet to come up with a uniformly adopted definition of culture, but the definition that we will use comes from cultural communication researcher, Donal Carbaugh (1988) who suggested that culture is “a learned set of shared interpretations and beliefs, values, and norms, which affect the behaviors of a relatively large group of people.” It is within this framework that we will explore what happens when people from different cultural backgrounds interact.

2.1 – Principles of Culture

Although the definition of culture is fairly straightforward, let’s break it down into parts and explore the important ideas implied within the definition. These ideas are foundational in the approaches to studying intercultural communication as well as the choice of content in this book.

Culture is Learned

Although there is a debate as to whether babies are born into this world as table rasa (a blank slate) or having intuition; we can say that they do not come with pre-programmed preferences like your personal computer or cell phone does. Human beings do share some universal habits like eating and sleeping, but these habits are biologically and physiologically based, not culturally based. Culture teaches us the ways of what to eat and how to sleep that we learn to view as “normal.”

In fact, culture becomes so ingrained within us, that we often do not even recognize that we have a culture or how it affects our everyday life choices. Some authors have described culture as a pair of glasses that we put on and forget that we are wearing. It’s only when someone mentions that you are wearing glasses that you remember the difference they make to your sight. Other authors have described culture as the water the water in an aquarium. The fish don’t realize that the water is there until a glass panel shatters, water drains, and the environment quickly changes.

Culture is Shared With a Relatively Large Group

A common misunderstanding about culture is that every individual comes with a personalized culture, but an important part of the definition of culture are the terms “shared” and “group.” Culture is something that is formed by a “relatively large groups” that has a “shared interpretation” or a shared perception of the world. What culture we learn is ultimately a matter of the group that we are born into. We don’t accidentally learn a culture.

Culture Teaches Beliefs, Values, Norms, and Behaviors

The culture that we are raised in will teach us our values, norms, beliefs, and accepted behaviors. Values are deeply felt and often serve as principles that guide people in their perceptions and behaviors. We use our values to judge right or wrong, good or bad, importance, and desirability. Ideally, our values should match up with what we say that we will do, but sometimes our various values come into conflict, and a choice must be made as to which one will be given preference over another. An example of this could be love of country and love of family. You might love both, but ultimately choose family over country when a crisis occurs. Common values include fairness, respect, integrity, compassion, happiness, and kindness.

The term “norm” is often used interchangeably with the term “rule.” Norms are informal guidelines that govern what is proper or acceptable behavior within a specific culture. Sometimes you don’t know what the norms are until you have violated the norm. Usually, there is a certain amount of forgiveness extended for the violation of norms. Rules, on the other hand, are explicit guidelines that are often written down and rigidly followed. Forgiveness is often not granted to rule-breakers.

Beliefs are strong assumptions, convictions, principles, tenets, and axioms held by individuals, groups or cultures about the truth, existence, or worth of something. Beliefs define for us, and give meaning to, objects, people, places, and things in our lives. These beliefs become our worldviews or shared values that form the customs, behaviors, and foundations of our culture. Worldviews are developed though our interactions within families, neighborhoods, schools, communities, and so on. Worldviews are resources for understanding and analyzing the differences between cultures.

Culture is Dynamic

In addition to exploring the stated components of the definition of culture, there is actually one more idea that should be added to the list of principles—and that is culture is not static, it is always changing. The United States your grandparents grew up in does not reflect the United States of today. Nor if you know one person from the United States, do you know them all. Within cultures there are struggles to negotiate and accommodate the forces of change. As Heraclitus, the ancient Greek philosopher noted, “change is the only constant in life.”

2.2 – Ways to Examine Culture

There are two primary ways in which culture has been identified and studied—as a structure and as a transaction. The most common approach is to view culture as a “national” structure. The structural study of culture focuses on large-scale differences in values, beliefs, goals and preferred ways of acting among nations, regions, ethnicities and religions. Obviously, there are limitations with the broad and simple nature of this approach, but it has also provided a wealth of information about what happens when cultures meet by providing a better understanding of different groups and improving interactions. From a communication point of view, we can study how all members of a structural or national group practice national beliefs, values, and behaviors along with communication patterns and styles.

The second approach to studying intercultural communication is focused on the transactional communication model introduced in chapter 1. The transactional study of culture focuses on the conformity of culture through the communication, interactions, contexts, and relationships that senders/receivers have with others in daily life. In this approach, values, beliefs, and behaviors is being transacted as a meaning system in communication therefore it leaves room to explore how styles of communication serve to include and/or exclude people within a culture.

Both approaches offer insights into our quest for greater understanding of intercultural communication. Both approaches also come with limitations that can hinder the understanding of intercultural communication. In an introductory course, it makes sense to broadly consider both approaches to add a richer depth to our exploration of communication across cultural boundaries.

2.3 – Foundational Research in Culture

If researchers have a difficult time defining, and figuring out the best ways to examine culture, it’s not easy to study either. “Our most cherished traditions [cultures] are only a tiny fraction of the many ways humans have devised for solving basic problems, from how to order society to how to mark the passage from childhood to adulthood (King, p. 11).”

This section will review research from cultural anthropologists to social psychologists and the impact that it has had on informing theories currently accepted within the field of intercultural communication. These theories will generally reflect the structural approach to the study of culture although the discussion of co-cultures and microcultures at the very end of the chapter will be more transactional in nature.

Value Orientation Theory

In an early effort to develop a cross-cultural theory of values, anthropologists Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (1961) suggested that every culture faces some basic human survival needs and must answer five simple questions. How those questions are answered by different cultures help to form a framework for understanding cultural differences. That framework is called the Value Orientation Theory. The basic questions fall into five categories and reflect concerns about: 1) human nature, 2) the relationship between humans and the natural world, 3) the nature of time, 4) the purpose of human activity, and 5) social relations between humans. Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck hypothesized three possible responses or orientations to each of the questions.

| Basic Concerns | Orientation | ||

| Human Nature | Evil | Mixed | Good |

| Relationship to natural world | Mastery | Harmony | Submission |

| Time | Past | Present | Future |

| Activity | Being | Becoming | Doing |

| Social relations | Collective | Collateral | Individual |

What is the inherent nature of human beings?

Some societies and/or religions are inclined to believe that people are inherently evil, and that the society must exercise strong measures to keep the evil impulses of people in check. On the other hand, some societies are more likely to see human beings as basically good and possessing an inherent tendency towards goodness. Between these two poles are societies that see human beings as possessing the potential to be either good or evil depending upon the influences that surround them. Societies can also differ on whether human nature is unchangeable and permanent or changeable and able to adapt.

What is the relationship between human beings and the natural world?

Some societies believe that nature is a powerful force in the face of which human beings are essentially helpless. We could describe this as “nature over humans.” Other societies are more likely to believe that through intelligence and the application of knowledge, humans can control nature. In other words, they embrace a “humans over nature” position. Between these two extremes are the societies who believe humans are wise to strive to live in “harmony with nature.”

What is the best way to think about time?

Some societies are rooted in the past, believing that people should learn from history and strive to preserve the traditions of the past. Other societies place more value on the here and now, believing that people should live fully in the present. Then there are societies that place the greatest value on the future, believing people should always delay immediate satisfactions while they plan and work hard to make a better future.

What is the proper mode of human activity?

In some societies, “being” is the most valued orientation. Striving for great things is not necessary or important. In other societies, “becoming” is what is most valued. Life is regarded as a process of continual unfolding. Our purpose on earth is to become fully human. Finally, there are societies that are primarily oriented to “doing.” In such societies, people are likely to think of the inactive life as a wasted life. People are more likely to express the view that we are here to work hard, and that human worth is measured by the sum of accomplishments.

What is the ideal relationship between the individual and society?

Expressed in another way, we can say the concern is about how a society is best organized. People in some societies think it is most natural that a society be organized by groups or collectives. They hold the view that some people should lead, and others should follow. Leaders should make all the important decisions for the group. Other societies are best described as valuing collateral relationships. In such societies, everyone has an important role to play; therefore, important decisions should be made by consensus. In still other societies, the individual is the primary unit of society. In societies that place great value on individualism, people are likely to believe that each person should have control over his/her own destiny. When groups make decisions, they often follow the “one person, one vote” principle.

Developments of the Theory

Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck themselves did not consider their theory to be complete and struggled to develop measures to test some of their own proposed value orientations. However, the theory itself has also generated much further research, which in turn has generated even more theories. Another major researcher that this book focuses on is Geert Hofstede who was heavily influenced by the Values Orientation Theory. As values are central to human thought, emotions and behaviors, Hofstede was able to use values to make between-group cultural comparisons.

Dimensions of Culture Theory

Geert Hofstede, sometimes called the father of modern cross-cultural science and thinking, is a social psychologist who focused on a structural study of culture. Hofstede identified how societies around the world prioritize values such as respect for authority, adaptability to change, whether they respect strength or sympathize with weakness, whether they are progressive or traditional, whether they value freedom to pursue happiness or view happiness as being determined by other factors, or whether they view the world through an individual or a collective lens. While such values may be common throughout all cultures, societies and nationalities may emphasize values differently.

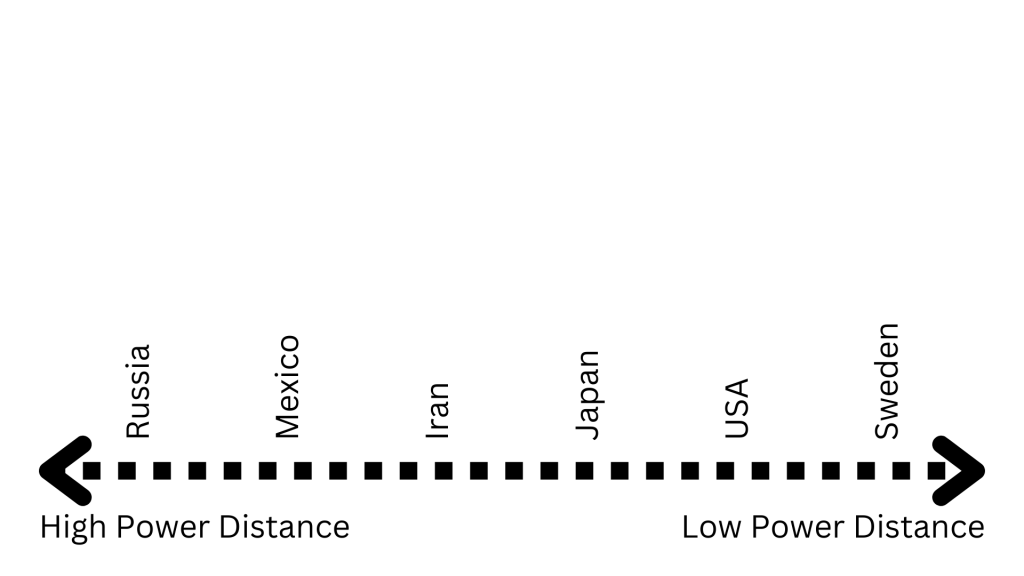

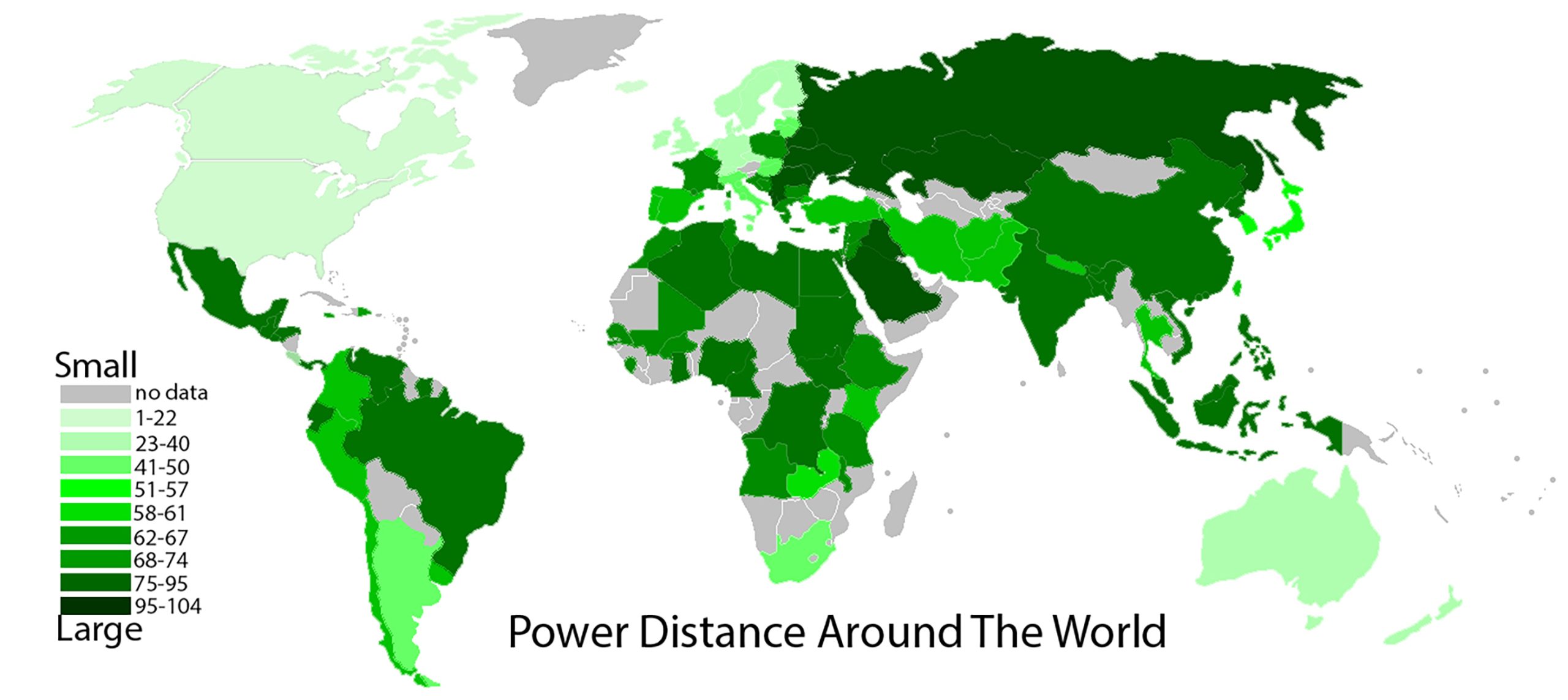

Power Distance

Power distance refers to how openly a society or culture accepts or does not accept differences between people, as in hierarchies in the workplace, in politics, and so on. For example, high power distance cultures openly accept that a boss is “higher” and as such deserves a more formal respect and authority. Examples of these cultures include Japan, Mexico, and the Philippines. In Japan or Mexico, the senior person is almost a father figure and is automatically given respect and usually loyalty without questions.

In Southern Europe, Latin America, and much of Asia, power is an integral part of the social equation. An individual’s status, age, and seniority command respect—they are what make it acceptable for the lower-ranked person to take orders. Subordinates expect to be told what to do and won’t take initiative or speak their minds unless a manager explicitly asks for their opinion.

At the other end of the spectrum are low power distance cultures, in which superiors and subordinates are more likely to see each other as equal in power. Countries found at this end of the spectrum include Austria and Denmark. To be sure, not all cultures view power in the same ways. In Sweden, Norway, and Israel, for example, respect for equality is a guarantee of freedom. Subordinates and managers alike often have the right to speak their minds.

Research indicates that the United States tilts toward low power distance but is more in the middle of the scale than Germany and the United Kingdom. The United States has a culture of promoting participation at the office while maintaining control in the hands of the manager. People in this type of culture tend to be relatively laid-back about status and social standing—but there’s a firm understanding of who has the power. What’s surprising for many people is that countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia actually rank lower on the power distance spectrum than the United States.

In a high power distance culture, you would probably be much less likely to challenge a decision, to provide an alternative, or to give input. If you are working with someone from a high power distance culture, you may need to take extra care to solicit feedback and involve them in the discussion because their cultural framework may preclude their participation. They may have learned that less powerful people must accept decisions without comment, even if they have a concern or know there is a significant problem.

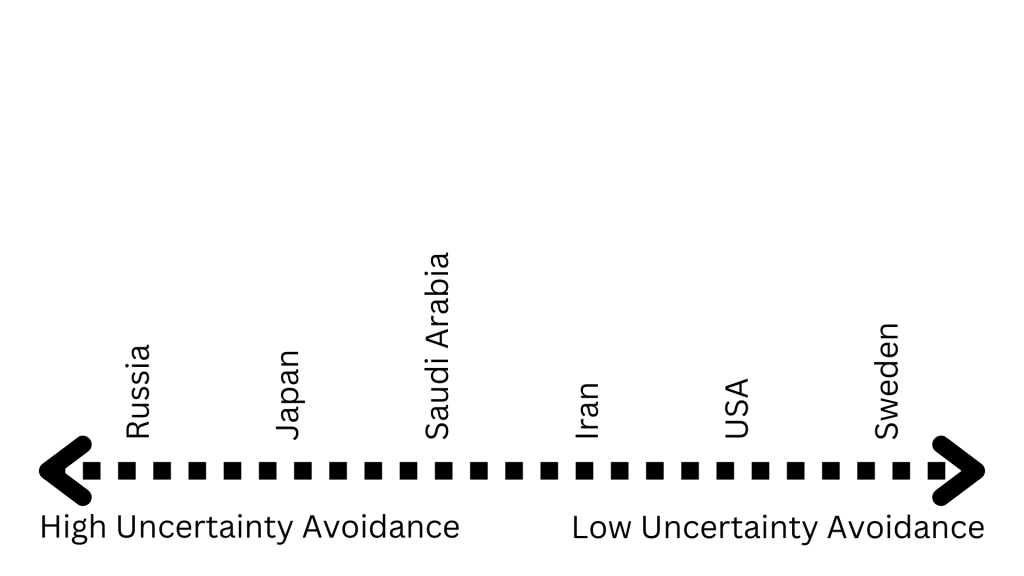

Uncertainly Avoidance

When we meet each other for the first time, we often use what we have previously learned to understand our current context. Our previous knowledge helps to reduce our uncertainty. People who have high uncertainty avoidance generally prefer to steer clear of conflict and competition. They tend to appreciate very clear instructions. They dislike ambiguity. At the office, sharply defined rules and rituals are used to get tasks completed. Stability and what is known are preferred to instability and the unknown.

Some cultures, such as the U.S. and Britain, are highly tolerant of uncertainty, or have low uncertainty avoidance. They tend to accept or embrace change and are willing to take risks. A business negotiator might enthusiastically agree to try a new procedure, while they work out all the details. People from countries with low uncertainty avoidance don’t mind it when a teacher says, “I don’t know. Let’s find out together.”

Berger and Calabrese (1975) developed uncertainty reduction theory to examine this dynamic aspect of communication. Here are seven rules of uncertainty:

- There is a high level of uncertainty at first. As we get to know one another, our verbal communication increases, and our uncertainty begins to decrease.

- As nonverbal communication increases, uncertainty will continue to decrease, and we will express more nonverbal displays of affiliation, like nodding one’s head to express agreement.

- When experiencing high levels of uncertainty, we tend to increase our information-seeking behavior, perhaps asking questions to gain more insight. As our understanding increases, uncertainty decreases, as does the information-seeking behavior.

- When experiencing high levels of uncertainty, the communication interaction is not as personal or intimate. As uncertainty is reduced, intimacy increases.

- When experiencing high levels of uncertainty, communication will feature more reciprocity, or displays of respect. As uncertainty decreases, reciprocity may diminish.

- Differences between people increase uncertainty, while similarities decrease it.

- Higher levels of uncertainty are associated with a decrease in the indication of liking the other person, while reductions in uncertainty are associated with liking the other person more.

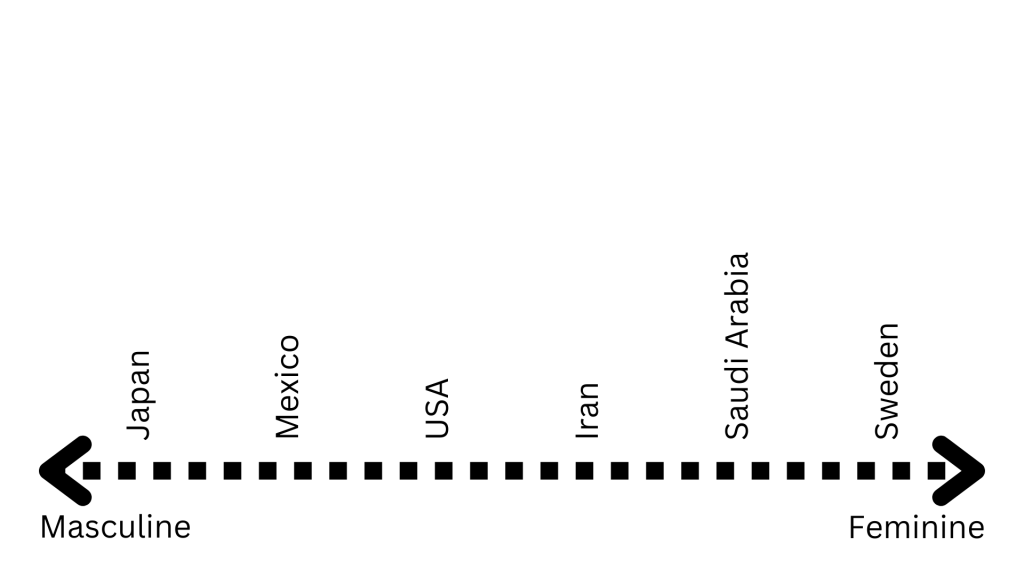

Masculinity versus Femininity

The masculine and feminine orientation refers to the distinctions that exist between women’s and men’s roles in society. Societies that score higher on the masculinity scale tend to value assertiveness, competition, and material success. Cultures in Japan and Latin American are examples of masculine-oriented cultures.

Societies that score higher on the femininity scale tend to embrace values that are more widely thought of as feminine values, such as modesty, quality of life, interpersonal relationships, and greater concern for the disadvantaged of society. The Scandinavian cultures rank as feminine cultures, as do cultures in Switzerland and New Zealand. Societies high in masculinity are also more likely to have strong opinions about what constitutes men’s work versus women’s work while societies low in masculinity permit much greater overlapping in the social roles of men and women.

It’s important to remember that cultures don’t necessarily fall neatly into one camp or the other. The United States is more moderate, and its score is ranked in the middle between masculine and feminine classifications.

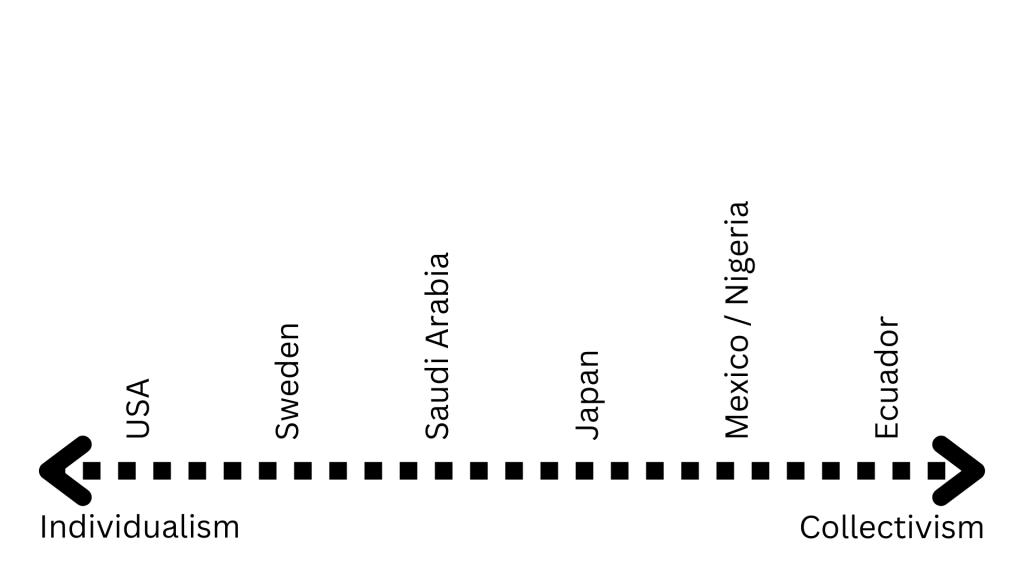

Individualism versus Collectivism

Individualism and collectivism might be the most important theory to explain cultural differences that you learn about in this book. Some researchers have speculated that most cultural differences can be explained by this one theory. You might also hear this dimension referred to as “independent” and “interdependent” because it refers to how people define themselves and their relationships with others.

Individualism is just what it sounds like. It refers to people’s tendency to take care of themselves and value individual accomplishments. People are defined by what they do, and not by the groups that they belong to. In individualistic cultures the interests of the individual receive more emphasis than those of the group. Personal dreams, goals, and achievements plus the right to make choices and have individual rights is paramount. Personal value is determined by accomplishments. Communication is more direct. Competition is the fuel of success.

In the United States, individualism is valued and promoted—from its political structure (individual rights and democracy) to entrepreneurial zeal (capitalism). Other individualistic countries include the United Kingdom, Australia, and Northern Europe.

Collectivistic cultures put more emphasis on the importance of relationships, loyalty, and working together. Memberships in particular groups, societies or families and working for the common good is incredibly important in defining individual worth and responsibilities. Personal value is based on your place in a system more than your special and unique qualities as a human. Communication is often more indirect in collectivistic societies. Cooperation with other group members is expected. South Korea is considered collectivistic whereas Japan falls close to the middle.

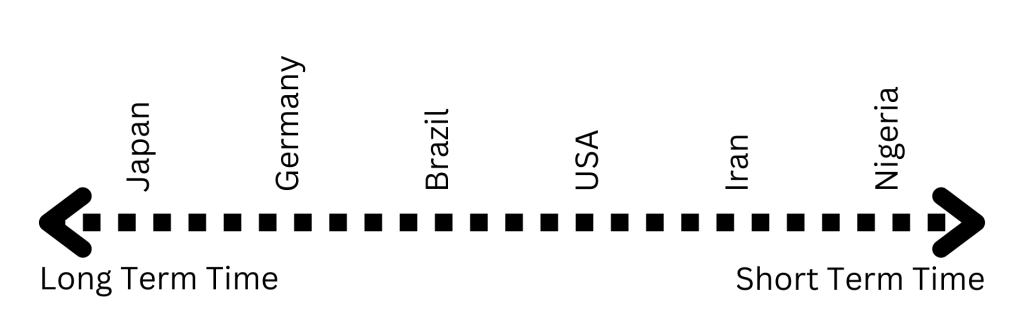

Measuring Time – Long Term versus Short Term

An important values dimension is the measurement of time. This dimension was added by Hofstede after the original four you just read about. It resulted in the effort to understand the difference in thinking between the traditional Eastern cultures and the traditional Western cultures. The long-term orientation is often marked by persistence, thrift and frugality, and an order to relationships based on age and status. A sense of shame, both personal and for the family and community, is also observed across generations. What an individual does reflects on the family and is carried by immediate and extended family members.

The short-term orientation values tradition only to the extent of fulfilling social obligations or providing gifts or favors. While there may be a respect for tradition, there is also an emphasis on personal representation and honor, a reflection of identity and integrity. These cultures are more likely to be focused on the immediate or short-term impact of an issue. Not surprisingly, the United Kingdom and the United States rank high in short-term orientation.

Other Cultural Theories

Today, the Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck’s value orientation along with Hofstede’s dimensions of culture are joined by many attempts to study human values within structural cultures. Rokeach (1979) and Schwartz (2006) have also produced value concepts that attempt to bring insight into the similarities and differences between human beings from different cultural backgrounds.

Hill (2002) has proposed a number of additional questions and dimensions that one might expect cultural groups to grapple with as well. These include:

- Space – Should space belong to individuals, to groups (especially the family) or to everyone?

- Work – What should be the basic motivation for work? To make a contribution to society, to have a sense of personal achievement, or to attain financial security?

- Gender—How should society distribute roles, power, and responsibility between the genders? Should decision-making be done primarily by men, women, or by both?

- Relationship Between the State and Individual—Should rights and responsibilities be granted to the nation or the individual?

Coming chapters will contain more specific theories that help us explain how cultures apply value orientation and dimensions of culture to the communication processes that we discussed in chapter 1, but first we have two more distinctions to make in our understanding of culture.

2.4 – Foundational Research in Culture

Structural culture is a powerful force that shapes and defines people’s ways of seeing the world, but within any society, there are many different groups with unique values that interact with each other. These different groups are not the focus of this particular book, but it is important to understanding what co-cultures and micro cultures are and how they interact with the dominant or structural culture to avoid confusion in future communication classes.

In addition to a dominant culture or structural culture, most societies have various co-cultures that exert influence on groups of people. In section 2.2, there was a discussion about the transactional study of culture. Co-cultural and microcultural theory evolved from the transactional study of culture and communication.

Co-Cultural Communication

A co-culture is a group of people whose values, beliefs, and behaviors set it apart from the larger culture, which it is a part of and with which it shares many similarities. Dominant cultures may have many co-cultures that thrive within them. Co-cultures can be regional, economic, social, religious, ethnic, LGBTQIA+ and more. Some co-cultures develop among people who share specific beliefs, ideologies, and life experiences. Co-cultures can also bring a unique sense of history and purpose within a dominant culture through their holidays and traditions. It is quite common for dominant cultures to co-opt parts of a co-culture and adopt it. Examples from the US could be Cinco de Mayo and St. Patrick’s Day which have become reasons to drink and have lost their historical and religious beginnings.

Interactions between dominant and co-cultures are directly related to the abilities of the co-cultures to negotiate power and relevance through formal and informal institutions of the dominant cultures. During the negotiation processes, some co-cultures gain more power, and some remain underrepresented. Studying and understanding these processes can be accomplished using co-cultural theory (Orbe, 1998), and is explored in great depth in other wonderful communication classes with a transactional approach to the study of culture.

Microcultural Communication

Different than a co-culture, a microculture is sometimes called a “local” culture and refers to cultural patterns based on a specific locality or within a specific organization. The importance of microcultures goes back to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs or the need for belonging. We all feel the need to belong, and these microcultures give us a sense of belonging on a localized level.

Lots of research has been done on classrooms as microcultures. Depending on the students, the teacher, the time, and the physical space of the classroom, you can end up with very different experiences even if the content of the class is the same.

Another well-researched microculture is the Disney theme parks. Cast members (called employees in the outside world) go to Disney University which is run by the Disney Institute and learn the “Disney Traditions.” Disney intentionally creates a very specific microculture.

2.5 – Conclusion

Someone once described culture as a “monster” because it was messy, too big to handle, and scary when you don’t know what you are dealing with. This chapter should help us apply a framework to organize culture so that as we identify values, we can start to see why various norms, and behaviors reflect the worldviews of a people. The Values Orientation Theory proposed questions that all cultures must answer as they develop. The Dimensions of Culture Theory gave us important dimensions that can be measured for comparisons across cultures.

From a communication process standpoint, the culture can be found in senders/receivers as well as the message, channel, and context. This book focuses on the theories of structural culture, whereas the theories of transactional culture help with our understanding of co- and microcultures.

The next chapter will highlight the self and identity aspect of senders/receivers in the communication process. Unsurprisingly, culture plays a role in how you view yourself and the identities you willingly adopt or the identities that a culture will assign to you.

Key Terms

- Culture

- Values

- Norms

- Beliefs

- Worldviews

- Structural study of culture

- Transactional study of culture

- Value Orientation Theory

- Dimensions of Culture Theory

- Power Distance

- Uncertainty Avoidance

- Long Term/Short Term (Time)

- Individualism

- Collectivism

- Masculine/Feminine

- Co-culture

- Microculture

Reflection Questions

- Can you think of any specific rituals, beliefs, values or behaviors (worldviews) that you and other members of your culture might participate in? Name two and describe them.

- Why do we hold stereotypes? Are they inherently bad? Why or why not? What is the difference between stereotypes and generalizations?

- What is the role of values in intercultural communication? Is it possible to reach agreement even when core values differ? Why or why not?

- What do we mean by the statement, “Trying to understand one’s own culture is like trying to explain to a fish that it lives in water”? Why is this statement significant in our learning about culture?

- How is culture learned? Do you remember a time when you were taught cultural traits, values, rituals, or behaviors? What were they–and who did you learn them from?

“A learned set of shared interpretations and beliefs, values, and norms, which affect the behaviors of a relatively large group of people.”

Deeply felt and often serve as principles that guide people in their perceptions and behaviors.

Informal guidelines that govern what is proper or acceptable behavior within a specific culture.

Strong assumptions, convictions, principles, tenets, and axioms held by individuals, groups or cultures about the truth, existence, or worth of something.

Shared values that form the customs, behaviors, and foundations of culture.

Focuses on large-scale differences in values, beliefs, goals and preferred ways of acting among nations, regions, ethnicities and religions.

Focuses on the conformity of culture through the communication, interactions, contexts, and relationships that senders/receivers have with others in daily life.

Proposes that all human societies must answer a limited number of universal questions and how those questions are answered by different cultures form a framework for understanding cultural differences.

Cultures openly accept that a boss is “higher” and as such deserves a more formal respect and authority.

Cultures that are more egalitarian or equal.

People who generally prefer to steer clear of conflict and competition.

Cultures are highly tolerant of uncertainty and they tend to accept or embrace change and are willing to take risks.

Value assertiveness, competition, and material success.

Embrace values that are more widely thought of as feminine values, such as modesty, quality of life, interpersonal relationships, and greater concern for the disadvantaged of society.

Refers to people’s tendency to take care of themselves and value individual accomplishments.

Cultures that put more emphasis on the importance of relationships, loyalty, and working together.

Often marked by persistence, thrift and frugality, and an order to relationships based on age and status.

Values tradition only to the extent of fulfilling social obligations or providing gifts or favors.

A group of people whose values, beliefs, and behaviors set it apart from the larger culture, which it is a part of and with which it shares many similarities.

Sometimes called a “local” culture and refers to cultural patterns based on a specific locality or within a specific organization.