Chapter 9 – Tourism

Learning Outcomes

When you have completed this chapter you should be able to do the following:

- List and define the impacts of tourism.

- Understand the ways that tourists and host interact and how that has an impact on tourism.

- Explain the intercultural communication challenges of tourism.

- Explore the types of tourism including new media.

- Learn how to prepare to be a competent tourist.

Almost as long as humans have emerged into societies, there has been tourism. Evidence of tourism has been found by archaeologists in ancient Egyptian and Babylonian sites, but it was probably in existence even before then. At that time, people probably traveled to religious sites, or to find food, or avoid war and invaders. Travel for leisure wasn’t documented until the rise of the Roman Empire when people had more money and a reliable road system.

During the European period called the Middle Ages, commoners started doing religious pilgrimages. Elites in the 1700s often did the “Grand Tour” of Europe to be considered cultured, but it wasn’t until the mid-1900s that tourism rose dramatically in the United States.

History aside, tourism provides rich opportunities for intercultural encounters. “Tourism is centered on the fundamental principles of exchange between peoples and is both an expression and experience of culture. It reaches into some deep conceptual territories relating to how we construct and understand ourselves, the world, and the multilayered relationships between them” Dimitrova, et al., 2015, p. 225). Outside of our exposure to the various forms of popular culture, tourism is the next biggest way that we are exposed to cultures other than our own. This chapter considers the economic impacts of tourism along with the challenges and cultural implications of tourism.

9.1 – Impacts of Tourism

The travel and tourism industry is one of the world’s largest industries. Statista.com (ret. 7/26/19) estimates that the global economic contribution of tourism in 2016 was over 7.6 trillion US dollars. This is amazing, considering the tourism industry has experienced growth almost every year. International border crossings increased from 528 million in 2005 to 1.19 billion in 2015 with a forecast of 1.8 billion by 2030. Each year, Europe receives the most international border crossings, but it also produces the most travelers with 607 million outbound in 2017. This constitutes a huge movement of people and a large transfer of resources. International tourism is booming, but it’s important to remember that many people travel within their own country. Only about 25% of tourists actually cross national boundaries (Orion, 1982).

Challenges to Tourism

The Great Recession of 2007-2010 popularized a relatively new form of tourism called the staycation. A staycation is an alternative to the traditional vacation and is influenced by such things as economic conditions, availability of discretionary income, and time. One might spend time in their home country visiting local and regional parks, museums, and attractions rather than going abroad. In the larger, more geographically isolated countries, such as the United States and Canada, local and regional travel has probably always been the norm, whereas travelers from the European nations probably expect to cross national boundaries on vacation.

The tourism industry was one of the hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving not only companies but also tourist driven economies severely effected by shutdowns, travel restrictions, and the disappearance of tourists. The World Economic Forum estimates that in 2020 alone that the travel and tourism sector lost $4.5 trillion and 62 million jobs globally (WEF, 6/22). The abrupt halt also caused many travelers to reconsider the staycation or community-based tourism, and the impact of tourism on the climate and environment. Recovery tourism seems to be focused on reconnecting with family and friends along with wellness (WEF, 6/22)

Downturns in the Global Economy

Tourists consider a multitude of factors when deciding where they should or should not go. One such factor is politics. A country’s “visitor-friendly” policies are important. Does travel require a passport or visa? Are they easy to obtain? Are they costly? Does the ruling party encourage or discourage visitors?

Instability can have devastating consequences on tourism, but even the perception of political trouble can affect tourism. In recent times, Qatar tourism was largely impacted by a political decision. The UAE and other countries in the region banned travel to and from Qatar. As most tourists to Qatar were from neighboring states, tourist numbers dropped leading to an economic downturn.

Tourism can exacerbate political tensions through environmental disasters as well. Tourism can increase the price of housing, land, goods, and services thereby increasing the cost of living. Imported labor may be needed to support tourist demands unfulfilled through local populations. There might also be additional costs to support the infrastructure needed for tourism such as water, sewer, power, fuel, hospitals, roads, and transportation systems. Plus, tourism uses resources and generates waste well more than local population needs. Without a planning and oversight system, tourism can add problems to an already strained political system.

Overtourism

The word “overtourism” is a relatively new term, but the meaning is clear. Overtourism is when an excessive number of tourist visits to a popular destination or attraction results in damage to the local environment and in poorer quality of life for residents. In other words, there is a limit to the volume any place can reasonably sustain before it and its resources are overwhelmed. Nearly 5000 tourists go to Machu Picchu, Peru each day so the government has started implementing restrictions of timed tickets and daily attendance restrictions. Such restrictions are also in place in Venice, Italy, Dubrovnik, Croatia, the living root bridges in Nohwet, India, and Glacier National Park, Montana.

9.2 – Communication Challenges with Tourism

Coping with tourists can be a complex process involving social, political, and economic contexts. As such, this book will only introduce general topic areas. Valid questions exist about the ethics of resource consumption, power inequities, standard of living, and cost-benefit distribution along with the consequences of a culture becoming public property. From a communication studies perspective, the challenges we are concerned with involve attitudes of hosts/tourists, characteristics of tourist/host encounters, language issues, social norms, and culture shock.

Attitudes of Hosts and Tourists

Tourism acts as a vehicle to provide direct encounters between people of diverse cultural backgrounds; therefore, tourism is a social activity in which the relationship between hosts and guests is fundamental to the experience.

Traditionally, a host is a person who invites and receives visitors. In the tourist context, we refer to the people who live in the tourist region as hosts. Please remember that most hosts have not invited the tourist, nor do they particularly welcome them.

Hosts reflect four general attitudes towards tourists.

- One attitude of hosts towards tourists is retreatism. A host reflecting retreatism basically means that the host actively avoids contact with tourists by looking for ways to hide their everyday lives. Tourists may not be aware of this attitude because the host economy may be dependent upon tourism. Such dependence could possibly force the host community to accommodate tourists with tolerance. Hawaii is a place that depends heavily on tourism and often uses various forms of retreatism to cope with the huge number of tourists. Several students have noted that other than people who worked at restaurants or tourist attractions, they didn’t see many locals when vacationing in Hawaii.

- Another attitude of hosts towards tourists is resistance. This attitude can be passive or aggressive. Passive resistance may include grumbling, gossiping about, or making fun of tourists behind their backs. Aggressive resistance often takes more active forms, such as pretending not to speak a language or giving incorrect information or directions. Deserved or not, the French have a reputation of tourist resistance. As Paris has been the number one city for international tourists in the world for many years, plus during the tourist season the population doubles or triples with visitors, it is not surprising that Parisians have developed a resistant attitude.

- Boundary maintenance is also a common way to regulate the interaction between hosts and tourists. This attitude is a common response by hosts who do not want a lot of interaction with tourists. A community may be dependent upon the economics of tourism but prefers to encounter tourists on a limited level–possibly only in specific locations or only with specific people. Many Native American tribes and First Nations people prefer to have visitors start at a tribal welcome center or museum before wandering around their reservations or traditional lands. All-to-common horror stories exist of tourists walking into private homes to meet “real Indians” and see how they live.

- Not all host attitudes are protective or negative. Some communities may capitalize on tourism and accept it as the social fabric of their community. Other communities actively invest money to draw tourists to create economic opportunities. Other communities passively accept community members who actively develop tourism opportunities to keep the community from dying. This attitude is called revitalization. Residents do not always share equally in the revitalization, but sometimes it does lead to pride in the re-discovery of community history and traditions. Dolly Parton’s “Dollywood” located in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee was created to revitalize the community that she loved. Disneyland serves a similar function in Southern California.

Within the same community, hosts can have a variety of attitudes towards tourists. These differences can be major sources of conflict that cause on-going strife throughout the community. It’s important that tourists be aware of their own attitudes towards tourism and acknowledge the cultural differences between hosts and tourists.

Characteristics of Tourist and Host Interactions

Much has been written about the characteristics of tourist and host encounters in all the various shapes and forms it occurs. The newest research tends to focus not on the encounter itself, but rather the context in which the encounter occurs. In general, there are a few concepts that are basic to tourist/host encounters from an intercultural perspective.

First, most encounters are very predictable and ritualistic because they are business transactions and nothing more. If you are thirsty, you can buy something to drink from a vendor, market, or restaurant. You ask as politely as you know how, exchange money, and receive a product. Once you have learned the ritual, you use it repeatedly throughout your visit.

Most tourists don’t have time for lengthy interactions, which leads to fewer opportunities to authentically engage with the hosts. Package tours are infamous for short time schedules, but free-range tourists often try to fit in as many local attractions as they can in one day before moving to the next location. Such commodification leads to great Instagram pictures, but little time to interact with the locals on a meaningful level.

Another characteristic of the tourist/host encounter is that tourists are often—but not always–more economically and socially privileged than their hosts. Traveling can be expensive so tourists are often looking for a good deal or places where their money can go farther than at home. Maybe they splurge on something normally inaccessible to them at home, but within their budget as a tourist. Such actions are part of normal tourist expectations but can lead to power imbalances between hosts and tourists.

Research indicates that contact between hosts and tourists is significantly more positive if tourists slow down and take an interest in the country they are visiting and the culture they are experiencing. It is also clear that when hosts have the time and space to treat tourists like guests, while taking pride in their own communities, hosts are most likely to welcome interaction with tourists.

Language Challenges

Not surprisingly, language is often a problem for both hosts and tourists. No one can learn all the languages of the places they might visit or of the people who visit them. Perceptions of service, inability to interact, and the lack of language resources are all huge frustrations for both sides.

Host cultures often have very different expectations of tourists regarding language usage as well. Some host cultures expect tourists to use the host language in interactions whereas other host cultures believe that they should provide language assistance for tourists. Language difficulties are often the basis for culture shock experienced by both the host culture and the tourists.

Social Norms and Expectations

People do not behave randomly; they have been taught the social norms and expectations of their home culture. For example, people visiting a tourist site may avoid littering because the site is clean, because they have been taught to be environmentally responsible. Whereas the community may support recycling programs at the site because they believe that tourists are willing to pay extra for eco-friendly practices.

Social interaction in public ranges from informal to very formal from culture to culture. Most cultures have expectations for gender- and age-related interactions. Some accepted conventions may have speakers address status with a formal relational title such as “honored grandmother” or “small friend” whereas a more informal convention would be “Florence” and “Ryann.” Social interaction norms may also be related to religious beliefs, traditions, politeness, and more.

Norms for shopping experiences also vary from culture to culture. One culture might be expecting that consumers touch the merchandise before buying it, but in other cultures touching might be forbidden until after the purchase. Bargaining might be the norm, and initial prices are given as higher than the expected purchase price or the price on the tag is the price you pay, and bargaining is not an option.

Communication styles (see the verbal chapter) also dictate how people act in public. Direct cultures will still ask questions that they want to know the answer for and expect to hear a direct answer. Indirect cultures will still avoid asking direct questions but strive to provide clues in the context of the situation. Some cultures value elaborate speakers and some value being concise. Conversations might involve grabbing a hand or arm to emphasize sincerity or avoidance of physical contact with others is expected. Information about the appropriate behavior is all around you. Observe what the host/tourists usually do and act accordingly.

Learn a little more!

10 Grocery Store Etiquette Rules in the United States

- Don’t yell at the checker.

- Bring a reusable tote instead of one-use bags provided by the store.

- Children sometimes have a mind of their own, so parents are not always to blame.

- If you break it, you buy it.

- Ask for a mop if you make a mess.

- Don’t judge the contents in the cart of someone else.

- If using a check, pre-write as much as you can while waiting.

- It’s okay to avoid people you know if you don’t have time to talk.

- Don’t text and push a cart at the same time.

- When you are done, park your cart in a designated place.

HowStuffWorks.com (Curran, retrieved 7/30/19)

Cultural Dimensions

People from different cultures are different in their behavior and value systems. These differences have been discussed in greater depth other places in the book, but just as a reminder, tourism can bring out some significant differences of cultural dimensions. Individualism and collectivism will account for many differences, but differences in power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity/femininity can also be present. Time orientation such as future versus past-oriented can matter as well. Not to forget being verbally direct or verbally indirect and high or low context plays a part. Nonverbally, cultures use space, territory, and gestures differently. They can also be tight or loose.

In the relationship chapter, we discussed relationship attractors where the idea that people prefer to develop relationships (help, work, play, trust, and live) with people that they perceive are like themselves compared to persons who are seen as different also applies to tourists. Both hosts and tourists will characterize the other as either an in-grouper or an out-grouper.

Cultural value dimensions and orientations matter in all aspects of intercultural communication, but are especially influential in tourist-host interactions.

Culture Shock

Being in new cultural contexts can lead to culture shock and feelings of disorientation. Even the physical aspects of traveling (crossing time zones, changes in food, etc.) can be difficult for some tourists. One student mentioned experiencing culture shock as a naive 16-year-old in Mexico. She didn’t understand the language and was freaked out by all the lizards in her room. She couldn’t wait to get home and feel “normal.”

Not all tourists experience culture shock. Many variables, including purpose of the trip, power dynamics, mental & physical health, and types of contact influence whether of culture shock occurs or not. New research proposes that culture shock can be negotiated at home before the trip even begins (Moufakkir, 2013). An important issue to note is that when tourists do experience culture shock, they often take it out on the host community.

Although culture shock has already been discussed in greater depth in a previous chapter, it’s important to remember that both hosts and tourists can experience culture shock. When hosts encounter new values and behaviors, they can reach a point of uncertainty and confusion as well. Researchers (Prokop, 1970; Furnham & Bochner, 1989) who examined culture shock experienced by host cultures noted higher incidence of alcoholism, depression, and minor psychiatric illness.

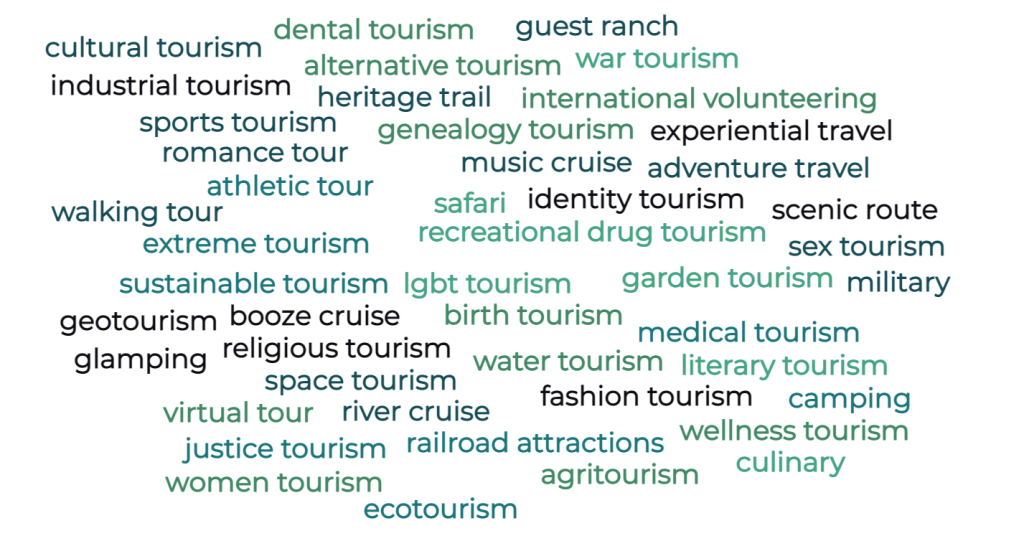

9.3 – Types of Tourism

Although we tend to think that all tourist experiences are the same, in today’s world, this is not the case. As the economy changes, pandemics loom, and staffing shortages hinder travel, the idea of what travel can be has also changed. Even though there are dozens of types of tourism that exist, there is not space to discuss them all. Below you will find a short explanation of some of the most popular types.

A big concern among the younger generation is sustainable tourism of all types (WEF, 2022). Younger consumers are very conscious of the impact they have, not only on the environment, but also socially within the communities they live in. They are putting pressure on the tourism industry in terms of planning and anticipating the problems associated with tourism. The common message to reuse towels in hotels in an effort to conserve water was created for just this purpose.

There are many definitions of ecotourism, but the idea is similar to sustainable tourism. Ecotourism is about uniting conservation, communities, and sustainable travel. There are direct financial benefits for conservation, and the local community. Tourists can meet local artisans, stay in locally owned accommodations, participate in ancestral traditions that help them connect with the locals or become a voluntourist (vacation with a service project).

Heritage and cultural tourism are also becoming increasingly popular. Cultural or heritage tourism refers to travel that is motivated by one or more aspects of the culture of a particular area. Cultural tourism helps people experience different ways of life or gain firsthand knowledge of an understanding of customs, traditions, physical environment, intellectual ideas, architecture, history, archaeological, ecology, specific events, and more. Cultural tourism differs from recreational tourism in that it seeks to gain an understanding or appreciation. Examples include popular heritage trails in South Korea and Japan that offer short walks combined with rustic accommodations at local temples or an architectural tour of New Orleans, Louisiana in the US.

9.4 – Tourism and New Media

Tourists and hosts are using new media as never before. Tourists are skipping the traditional ways of booking vacations and directly interacting with hosts and cultural organizations. Hosts are enticing, inviting, and advertising their experiences directly to the public. Free apps allow tourists and hosts to talk directly over the internet. Pre-departure information is no longer in the sole control of travel agents, airlines, and hotels.

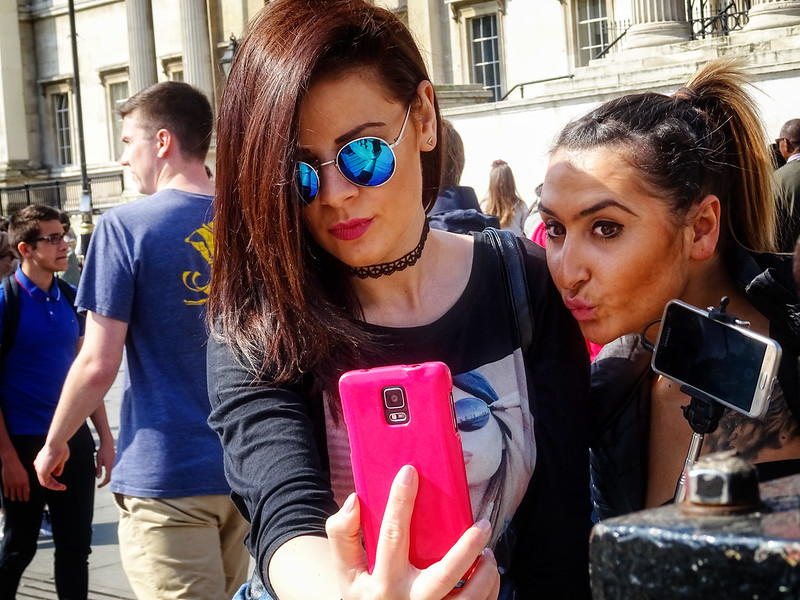

Fascinating research is being done by Thurlow & Mroczek (2014) that explores the ways that the micro-blogging (web-based self-reporting of short messages) is changing the tourist experience. Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter use self-reporting to share what one is doing, thinking, and feeling at any moment. Viewers can not only experience the trip in real time, but also plan the same experiences with the contacts provided.

Another new media impact on tourism is cyber tourism and virtual tourists. Cyber tourism is the application of new technologies such as GIS or Google Earth to create realistic experiences. Cyber tourism can lead to actual physical tourism, but for those without the time and money, or have other restrictions to prevent travel, new technologies offer a viable alternative.

Back in 2001, Lonely Planet noticed a group of people who would buy travel books, but never travel. They called these people, virtual tourists (Champion, ret. 7/30/2109). Today’s virtual tourist uses an enhanced virtual environment that can be seen through a headset or on a computer. This augmented reality merges the real and virtual world together into virtual reality. Although a new and emerging experience, various organizations such as museums, cultural groups, and travel agencies are beginning to offer this interesting way to “travel.”

The United Nations is also jumping into the tourism and travel industry with a non-governmental organizational (NGO) called E-Tourism. The aim of E-Tourism is to help developing countries make the most of their tourism potential without all the stress of environmental consequences. The internet is packed with plans and discussion of tourism potential from such varied places as Afghanistan to Botswana.

9.5 – Preparing to be a Good Tourist

Tourism is a wonderful thing. Seeing different parts of the world enriches our lives, offers opportunities to break free from our comfort zone, and broadens our horizons. Yet, while tourism may enhance our lives, we need to thoughtfully prepare ourselves to be competent tourists. Below you will find some suggestions to help you prepare for a visit to your next travel destination.

Sharing food, holding a conversation, or participating in a meaningful cultural event are all ways that one can learn about a different culture before going on a trip. Be observant and more conscious of your own and others’ communication. Read books and articles written by people from other cultures from their own cultural perspective. Follow social media of people from, or organizations that represent, other cultures. Learn another language. Enter a cultural exchange. Visit museums and cultural centers. Ask questions. Be flexible and open to other ways of living (gcorr.org).

9.6 – Conclusion

Tourism is one of the world’s largest and most complex industries. Most of us have been a tourist or have interacted with tourists. Much like our exposure to popular culture, our tourist experiences have formed and impacted our understanding of different cultures. There are intercultural communication challenges inherent in the tourist process. We must consider the attitudes towards tourists, tourist host encounters, language, cultural norms, and culture shock. In today’s world, there are many ways to be a tourist, and all of them are being impacted by new media. Tourism is not without costs to political structures and the environment.

At its best, tourism is a useful tool to share, sustain, and improve cultural diversity. At its worst, tourism can destroy a community and a culture. The reality of tourism is much more complicated than just taking a vacation.

Key Terms

- Tourism

- Host

- Resistance

- Revitalization

- Ecotourism

- Heritage Tourism

- Cyber-tourism

- E-Tourism

- Staycation

- Retreatism

- Boundary Maintenance

- Sustainable Tourism

- Cultural Tourism

- Micro-blogging

- Virtual Tourism

Reflection Questions

-

What do you consider when preparing to make a trip where you are going to be a tourist? Do you prefer a specific type of tourism? Do you research your location? Does sustainability matter to you?

-

What factors about being a tourist do you think would affect you the most as a tourist in another culture? Could you prepare for potentially challenging experiences? What could you do?

-

Our area gets a lot of sports and natural resources tourism. Do you have any experiences as a host culture representative? How did you react? Would you have done anything differently?

-

How has social media impacted your tourist experiences? Do you feel compelled to take certain pictures when you visit places so that you can “share” with your friends? Have you taken trips inspired by social media? Do you like to read social media reviews before or during your trip?

-

Tourism has a dark side. Have you ever thought about the dark side of tourism? Have you ever personally experienced the dark side of tourism? Do you plan on changing your plans now that you know about the challenges of tourism?

Centered on the fundamental principles of exchange between peoples and experiences.

An alternative to the traditional vacation and is influenced by such things as economic conditions, availability of discretionary income, and time.

A person who invites and receives visitors.

The host actively avoids contact with tourists by looking for ways to hide their everyday lives.

This attitude can be passive or aggressive.

This attitude is a common response by hosts who do not want a lot of interaction with tourists.

Communities passively accept community members who actively develop tourism opportunities to keep the community from dying.

Leaving a positive impact not only on the environment, but also socially within the tourist destinations.

Uniting conservation, communities, and sustainable travel with direct financial benefits for conservation, and the local community.

Relating to culture.

Travel that is motivated by one’s racial, ethnic or religious history.

Web-based self-reporting of short messages.

The application of new technologies such as GIS or Google Earth to create realistic experiences.

Uses an enhanced virtual environment that can be seen through a headset or on a computer.

Helps developing countries make the most of their tourism potential without all the stress of environmental consequences.