Chapter 3 – Self & Identity

Learning Outcomes

When you have completed this chapter you should be able to do the following:

-

Be able to explain how three components make up the idea of “self.”

- Explore the implications of identity.

- Identity and explain the different types of identity.

- Articulate the origin of in-groups and out-groups along with their roles in stereotyping, prejudice, and the ignorance of differences.

- Understand the three components that make up the “self.”

- Be able to explain how social comparison plays a role in self.

- Identify and define Co-cultural Communication Theory along with the role of in-groupers and out-groupers.

- Articulate what constitutes culture shock.

- Be able to discuss the various theories and models associated with culture shock.

At some point in our lives, we will wonder who we are. Our parents, friends, teachers, community, and media help shape our identities. While developing a sense of self happens from birth, most people in Western societies reach a stage in adolescence where they begin to reflect on who they are, and who they will become.

To understand intercultural communication, we need to look back at the communication process to understand what constitutes a sender/receiver or “self.” Along the way, we will also consider the formation of identities, differences, culture shock, and communication competence.

3.1 – Who am I?

Although each of us experiences ourselves as a singular individual, our sense of self is actually made up of three separate, yet integrated components: self-awareness, self-concept, and self-esteem.

Self-awareness can be defined in many ways, including “conscious knowledge of one’s own character, feelings, motives, and desires.” (Google Dictionary 2/4/19) In other words, noticing your feelings, your reactions, your thoughts, your behaviors, and more. As you are watching and observing your own actions, you are also engaging in social comparison, which is observing and assigning meaning to others’ behavior and then comparing it with your own.

Self-concept is your overall perception of who you think you are. Self-concept answers the question of who am I? Your self-concept is based on the beliefs, attitudes, and values that you have about yourself. Identity and self-concept strongly intertwined.

Self-esteem is how we value and perceive ourselves. Whether you feel positively or negatively about yourself, your self-esteem influences your communication.

In addition to self-awareness, self-concept, and self-esteem, our culture is a powerful source of self (Vallacher, Nowak, Froehlich & Rockloff, 2002). As we have previously learned, culture is an established, coherent set of beliefs, attitudes, values, and practices shared by a large group of people (Keesing, 1974). In other words, culture is like a collective sense of self that is shared by a large group of people.

3.2 – Identity

Thinking about intercultural communication in terms of self and identity has some important implications.

First, identities are created through communication. As messages are negotiated, co-created, reinforced, and challenged through communication, identities emerge. Different identities are emphasized depending on the topic of the conversation and the people you are communicating with. Second, identities are created in spurts. There are long time periods where we don’t think much about ourselves or our identities. Whereas other times, events cause us to focus on our identity issues and the insights gained modify our identities.

Third, most individuals have developed multiple identities because of membership in various groups and life events. Societal forces such as history, economics, politics, and communities influence identities. Fourth, identities may be assigned by societies, or they may be voluntarily assumed, but the forces that gave rise to particular identities are always changing.

Lastly, it is important to remember that identities are developed in different ways in different cultures. Individualistic cultures encourage young people to be independent and self-reliant whereas collectivistic cultures may emphasize interdependency and the family or group.

Personal, Social, and Cultural Identities

We must avoid the temptation to think of our identities as constant. Instead, our identities are formed through processes that started before we were born and will continue after we are gone; therefore our identities aren’t something we achieve or complete. Three related, but distinct components of our identities are our personal, social, and cultural identities.

Personal identities include the components of self that are primarily intrapersonal and connected to our life experiences. You may consider yourself a manga lover and a fan of K-pop. Our social identities are the components of self that are derived from involvement in social groups with which we are interpersonally committed.

We may derive aspects of our social identity from our family or from a community of fans for a sports team. Social identities differ from personal identities because they are externally organized through membership. Our membership may be voluntary (fraternity or sorority on campus) or involuntary (family). Membership may also be explicit (we pay dues to taxes to our local government) or implicit (we listen to music when studying).

While our personal identity choices express who we are, through our social identities we make statements about who we are and who we are not. Personal identities may change often as we have new experiences and develop new interests. Social identities do not change as often because they take more time to develop as you become more invested.

Cultural identities are based on social constructed categories that teach us a way of being and include expectations for social behaviors or ways of acting. Since we are often a part of them since birth, cultural identities are the least changeable of the three. The ways of being and the social expectations for behavior within cultural identities do change over time, but what separates them from most social identities is their historical roots. To be accepted as a member of a cultural group, members must be acculturated, essentially learning, and using a code that other group members will be able to recognize (Collier, 1996). We are acculturated into our various cultural identities in obvious and less obvious ways. We may literally have a parent or friend tell us what it means to be a man or a woman. We may also unconsciously consume messages from popular culture that offer representations of gender.

Any of these identity types can be ascribed or avowed. Ascribed identities are personal, social, or cultural identities that are placed upon us by others, while avowed identities are those that we claim for ourselves. Sometimes people ascribe an identity to someone else based on stereotypes.

Throughout history, cultural and social influences have established dominant and nondominant groups. Dominant identities historically had, and currently have more resources and influence, while nondominant identities historically had, and currently have less resources and influence. It’s important to remember that these identity distinctions are being made at the societal level, not the individual level. Because of this uneven distribution of resources and power, members of dominant groups are granted privileges and power, while nondominant groups can be at a disadvantage.

Although the topic of identities is weighty and important in the study of intercultural communication, this is as far as we are going to cover in a lower level communication course. Knowing the basics about the various types of identities and how they are formed prepares us to delve into more specifics about why identity differences matter.

3.3 – Difference Matters – Stereotypes, Prejudice, and “Aren’t We All the Same?”

Whenever we encounter someone, we notice similarities and differences. While both are important, it is often the differences that are highlighted and that contribute to communication troubles. We don’t usually perceive similarities and differences on just an individual level though. In fact, we place people into in-groups and out-groups based on the similarities and differences we perceive.

Your culture and identity is a strong influence on your perception. Whenever you interact with others, you interpret their communication by drawing on information from your previous experiences. Those experiences constitute assumptions, attributions and generalizations based on our experiences. Stereotypes can aid us in predicting behavior and reduce our feelings of uncertainty, but when we stereotype others, we replace human complexities of personality with broad assumptions about character and worth based on group affiliation. We stereotype people because it streamlines the communication process. Once we’ve categorized a person as a member of a particular group, you can form a quick impression of them (Macrae et al., 1999), which might be efficient for the communication process, but frequently leads us to form flawed impressions.

Although stereotyping is almost impossible to avoid, and most of us presume that our beliefs about other groups are valid, it’s crucial to keep in mind that just because someone belongs to a certain group, it doesn’t necessarily mean that all the defining characteristics of that group apply to that person. To assume you know something about a stranger, or even a friend, based on a stereotype will often make you look foolish, and likely hurt or offend the other person.

Prejudice involves a negative preconceived judgment or opinion that guides conduct or social behavior. Specific types of prejudice have their own labels that often end with -ism (e.g. racism, sexism, ableism, etc.) Treating people with prejudice is also about making assumptions or taking preconceived ideas for granted without question. Again, with potentially ignorant, and possibly even dangerous, consequences.

The flip side of emphasizing difference is to claim that no differences exist and that you see everyone as a human being. The trap of assumed similarity or thinking that all people are basically similar, denies cultural, racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and many other valuable insightful differences that are important to the human experience.

3.4 – Culture Shock

When a person moves to a cultural environment that is different than their own, they often experience personal disorientation called culture shock. It’s common to experience culture shock when you are an immigrant, visit a new country, move between social environments, or simply become stressed by trying to deal with lots of new cultural information all at once. The impact of culture shock intensifies due to the “need to operate” in unfamiliar and difficult contexts. Functioning without a clear understanding of how to succeed or avoid failure, along with modifying your normal behavior tends to compound the problem. As symptoms of culture shock intensify, your ability to function declines making culture shock an intensely disorienting.

Common symptoms of culture shock can include: homesickness, feelings of helplessness, disorientation, isolation, depression, irritability, sleeping and eating disturbances, and loss of focus. Although most people recover from culture shock fairly quickly, a few take much longer to recover, particularly if they are unaware of the sources of the problem, and have no idea of how to counteract it.

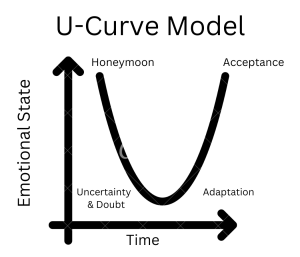

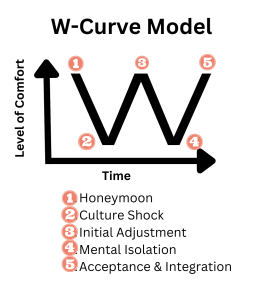

Many studies have been done culture shock. Most look at culture shock as steps or stages. There is the U-Curve Model (Lysgaard, 1955) that introduced the honeymoon, shock, recovery and adjustment stages. Or the W-Curve Model (Gullahorn & Gullahorn, 1963) suggested the stages of honeymoon, culture shock, initial adjustment, mental isolation, and plus acceptance & integration.

Adler (1975) proposed a “contact-disintegration-reintegration-autonomy-independence” model. Recently, it has been suggested that the curve models do not reflect reality and that there are factors or traits (e.g. routines, reactions, roles, relationships, and reflections) that are disrupted when moving across cultural boundaries (Berado, 2006).

While the idea of culture shock remains a useful term, some people never experience symptoms of culture shock while others become paralyzed and quickly flee back to their home cultures. There appears to be no one-size-fits-all model. Some people might skip certain stages, experience stages in a different order, or have a longer or shorter adjustment period. What researchers do agree upon is that it is natural to feel some degree of culture shock.

Advice for dealing with culture shock varies as much the symptoms and is dependent upon individual traits.

Helpful tips include:

- Be flexible and try new things.

- Get involved in the things that you already like.

- Do not expect to adjust overnight.

- Process your thoughts and feelings.

- Use the resources available to help you handle the stress.

3.5 – Intercultural Communication Competence

Intercultural communication is complicated, messy, and at times contradictory. Although much research has been done with the idea of competent communication within one’s own structural culture, Bennett (2009) has proposed three ways to cultivate intercultural communication competence (ICC). They are

- to foster attitudes that motivate us

- discover knowledge that informs us

- develop skills that enable us

To foster attitudes that motivate us, we must develop a sense of wonder about a culture. This sense of wonder can lead to feeling overwhelmed, humbled, and awed (Opdal, 2001) This sense of wonder may correlate to a high tolerance for uncertainty, which can help us turn potentially frustrating experiences we have into teachable moments. Maybe getting lost while trying to follow Google maps lead to meeting a family that helped you practice your language skills.

Discovering knowledge that informs us is another step that can make us more motivated and competent. As we discover that there are differences in how people attend to and perceive their world, we learn of their value orientations (remember Kluckhohn & Strodbeck?) and cultural dimension choices (remember Hofstede?). Suddenly there is no right or wrong between us, just different choices. Different choices become normal and natural.

Developing skills that enable us is another part of ICC. Some skills important to ICC are the ability to emphasize, accumulate cultural information, listen, resolve conflict, and manage anxiety (Bennett, 2009). You are already developing a foundation for these skills by reading this book. Contact alone does not increase intercultural skills; there must be more deliberate measures taken to fully capitalize on your experiences. While research now shows that intercultural contact does decrease prejudices, this is not enough to become interculturally competent. Reflection can also help us process the rewards and challenges associated with developing ICC. We should be ‘thinking under the influence.’

3.6 – Conclusion

Respectfully communicating across cultural differences starts with an understanding of the communication process. Understanding ourselves as communicators by considering our various identities and how they impact our perception of the world is just as foundational as considering the fundamentals of culture. Differences can lead to stereotyping, prejudice, and assumed similarity as well as steps towards intercultural communication competence. If we open our minds and cultivate a sense of wonder, we can learn to grow and communicate in a constructive way.

Key Terms

- Self-awareness

- Social comparison

- Cultural identity

- Avowed identity

- Stereotyping

- Culture shock

- Communication competence

- Self-concept

- Personal identity

- Acculturated

- Dominant identity

- Prejudice

- U-Curve model

- Self-esteem

- Social identity

- Ascribed identity

- Nondominant identity

- Assumed similarity

- W-Curve model

Reflection Questions

- What are some of the ways in which people within your culture express their identities? Are some ways more socially acceptable than others? Why or why not?

- How do you feel when someone does not recognize the identity that is most important to you? Do you educate them or ignore them? Why?

- How did you learn about several (explain 2) of your identities? Did someone teach you about them or did you learn on your own? What kinds of rules did you learn about these identities? Did you embrace, resist, or accept these identities? Why?

- What is culture shock? Why does culture shock occur to people who make cultural transitions? Explain.

- Do the stages outlined in the U-curve, W-curve, or other culture shock models reflect any travel or intercultural contact that you have experienced? If so, please explain. If not, why not? Did you prepare? Did you avoid people/situations that were different?

Noticing your feelings, your reactions, your thoughts, your behaviors, and more.

Observing and assigning meaning to others’ behavior and then comparing it with your own.

Based on the beliefs, attitudes, and values that you have about yourself.

How we value and perceive ourselves.

Include the components of self that are primarily intrapersonal and connected to our life experiences.

The components of self that are derived from involvement in social groups with which we are interpersonally committed.

Based on socially constructed categories that teach us a way of being and include expectations for social behaviors or ways of acting.

Earning and using a code that other group members will be able to recognize.

Are personal, social, or cultural identities placed on us by others. They are sometimes considered "involuntary" identities.

An identity that you choose for yourself. Also known as voluntary identities.

Historical and currently have more resources and influence.

Historically had, and currently have less resources and influence.

Social group to which a person psychologically identifies as being a member.

Groups with which an individual does not identify.

Replacing human complexities of personality with broad assumptions about character and worth based on group affiliation.

A negative preconceived judgment or opinion that guides conduct or social behavior.

Thinking that all people are basically similar, denies cultural, racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and many other valuable insightful differences that are important to the human experience.

Personal disorientation when a person moves to a cultural environment that is different than their own.

Introduced the honeymoon, shock, recovery and adjustment stages.

Suggested the stages of honeymoon, culture shock, initial adjustment, mental isolation, and plus acceptance & integration.

The ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in various cultural contexts.