Chapter 6 – Conflict

Learning Outcomes

When you have completed this chapter you should be able to do the following:

- Identify and describe the five types of conflict.

- Explain your experiences with the Tight-Loose Divide.

- Explain why face and facework important in conflict.

- Identify and understand the conflict styles.

- Identify the four ways to deal with conflict.

- Understand how and why individuals and cultures approach conflict in various ways.

- Explain the Seven-Step and Four-Skills Approach to managing intercultural conflict.

Conflict is a normal part of all human relationships (Canary, 2003). Almost any issue can spark conflict—money, time, religion, politics, culture—and almost anyone can get into a conflict. Conflict triggers strong emotions that can lead to unhealthy communication on the personal, societal, political, and international levels.

Some cultures view conflict as a positive thing, while others view it as something to be avoided. In the US, conflict is not seen as desirable, yet people are encouraged to deal with it directly when conflicts do arise. Meetings are seen as the best way to work through problems. In contrast, open conflict is considered embarrassing or demeaning in many Asian countries, so differences are worked out quietly. Trusting community members, mediators, or even written exchanges, are the preferred ways to indirectly address the conflict.

6.1 – Conflict Definition

Defining conflict is not simple because it’s not just a matter of disagreement. According to Wilmot & Hocker (2010), “conflict is an expressed struggle between at least two interdependent parties who perceive incompatible goals, scare resources, and interference from others in achieving their goals (p. 11).” Within this definition, there are several aspects of conflict that we must consider when exploring this definition and its application to intercultural communication.

Conflict is an Expressed Struggle

Conflict is a communication process that is expressed verbally and nonverbally. Wilmot & Hocker assert that communication creates conflict, communication reflects conflict, and communication is the vehicle for the management of conflict (Wilmot & Hocker, 1998). In cultures that are verbally direct or low context, conflict is easily identified because one party openly and verbally disagrees with the other. In cultures that are more indirect or high context, conflict may exist for some time before being expressed. In fact, conflict may never be verbally expressed making nonverbal communication cues extremely important.

Conflict is Interdependent

Parties engaged in conflict do so because they are interdependent. “A person who is not dependent upon another—that is, who has no special interest in what the other does—has no conflict with that other person” (Braiker & Kelley, 1979). In other words, each parties’ choices affect the other because conflict is a mutual activity.

Consider the teenager who chooses to wear an obnoxious or offensive t-shirt before catching the bus. People with no connections to the teen and notice the t-shirt are unlikely to engage in conflict. They have never seen the teen before, and probably won’t again. The ill-advised decision to wear the t-shirt does not impact them, therefore the reason to engage in conflict does not exist.

The same scenario involving a teen and their parents would probably turn out differently. Because parents and teens are interdependent, the ill-advised decision to wear an offensive t-shirt could quickly escalate into a power struggle over individual autonomy that leads to harsh words and hurt feelings.

Conflict is Perceptual

Parties in conflict have perceptions about their own position and the position of others. Each party may also have a different perception of any given situation. If I do not view something as a conflict, it may not seem to be an impediment to competent communication to me, and I will continue as if nothing has happened. Whereas if you view something as a conflict, it will be an impediment to competent communication to you, and will need to be addressed or negotiated or mediated before continuing on.

Conflict Involves Clashes in Goals, Resources, and Behaviors

Conflict arises from differences. It occurs whenever parties disagree over their values, motivations, ideas, or desires. The perception might be that goals are mutually exclusive, or there’s not enough resources to go around, or one party is sabotaging another. When conflict triggers strong feelings, a deep value is typically at the core of the problem. When the legitimacy of the conflicting values is recognized, it opens pathways to problem-solving.

6.2 – Types of Interpersonal Conflict

Conflict can be difficult to analyze because it occurs in so many different settings. Knowing the various types of conflict that occur in interpersonal relationships helps us to identify appropriate strategies for managing conflict. Mark Cole (1996) states that there are five types of interpersonal conflict: affective, interest, value, cognitive, and goal.

Rarely do the types of conflict stand alone. Most often, several types of conflict are found intertwined within each other and within the context itself. How we choose to manage the conflict may depend on the types of conflict, the contexts that they occur within, and the situation.

Affective conflict occurs when people become aware that their feelings and emotions are incompatible. For example, if a romantic couple wants to go out to eat, but one of the partners is a vegetarian while the other is on the Paleo diet, what do they do? The food choices that they have committed to may impact their feelings for each other causing them to question a future together.

Conflict of interest arises when people disagree about a plan of action or when they have incompatible preferences for a course of action. Another way to understand this idea is to use the term conflict of roles. For example, you may run a business where you employ relatives. Firing an incompetent relative can cause problems with family relationships for a long time.

A difference in ideologies or values between relational partners is called value conflict. Our romantic partners eating preferences may be the result of strongly held religious or political views. Remember the old saying, “Never talk about religion and politics.” Many people engage in value conflict about religion and politics.

Cognitive conflict is when people become aware that their thought processes or perceptions are in conflict. Our romantic partners may disagree about the meaning of a wink from a car salesman as they shopped for a new car. One of the partners believes that the wink was friendly and meant to build a relationship with the couple, but the other partner saw the wink as a sign that the couple would get a better deal if they looked seriously at a specific car.

Goal

Goal conflict occurs when people disagree about a preferred outcome or end state. Our car-shopping romantic partners need transportation. For one, the cost of a new car reinforces the choice made to continue using public transportation to save the money not spent for a house. For the other, buying a new car means gaining access to the suburbs where they can afford to buy a new house now.

6.3 – The Tight-Loose Divide

As we learned in the cultural foundations chapter, all cultures have social norms. Cultures vary in the strength of their social norms along a tight-loose continuum (Gelfand, 2018). There is a tension between personal liberties and societal constraint or in other words, somewhat like what Hofstedt called individualism and collectivism.

Gelfand’s research indicated that the degree of threat that cultures face from the outside world determines whether they evolve to be tight, loose, or somewhere in the middle. Countries such as China, Malaysia, Singapore, and Pakistan have survived threats like war, famines, and flooding by “tightening up.” Strict enforcement of social norms has been key to their survival.

On the other hand, cultures that have faced fewer threats have had the luxury of being loose. Loose cultures such as the US, the Netherlands, Spain, and Brazil have social norms that are more lax and offer more personal freedom. Loose cultures are known for creativity and innovation, but they can also be chaotic and have slower responses to crises such as Covid-19.

6.4 – Characteristics of Intercultural Conflict

Culture is always a factor in conflict, though it rarely causes conflict by itself. When differences surface between people, organizations, and nations, culture is always present, shaping perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and outcomes. Our cultural background, and how we were raised, largely determines how we deal with conflict, but there are also other lesser known issues that are important to consider in this discussion as well.

Ambiguity

Ambiguity, or the confusion about how to handle or define the conflict, is often present in intercultural conflict because of the multi-layered and heterogeneous nature of culture. What appears on the surface of the conflict may mask what is more deeply hidden below. Verbally indirect, high context cultures may be reluctant to use words to explore issues of importance that verbally direct, and low context cultures need to access the nonverbal codes that are largely outside of their awareness. Just remember that knowing the general norms of a group, does not predict the behavior of a specific member of a group. Individual differences and not just culture, can be crucial to understanding conflict.

Language

Language issues can also add to the confusion. Not knowing each other’s languages very well could make conflict resolution difficult, but remaining silent could also provide a needed “cooling off” period with time to think.

Name, Frame, Blame, and Tame

Communication researcher Michelle LeBaron (2003) explains another way that language impacts conflict with her name, frame, blame, and tame approach to dissecting conflict. She believes that the Western approach to conflict resolution often means labeling with language and analyzing with language the smaller component parts of an issue (name, frame, blame), before a resolution (tame) can be proposed. The Eastern approach to conflict resolution often means reinforcing all aspects of the relationship (tame), before ever discussing the issue (name, frame, blame)–if at all. In the Eastern approach, language is more of a means of creating and maintaining identity than solving a problem.

Face and Facework

The term “face” is probably known to many of us, but it’s also an important concept in conflict. To lose face is to publicly suffer a diminished self-image, and saving face is to be liked, appreciated, and approved by others. Brown & Levinson (1987) use the concept of face to explain politeness, and to them politeness is value present in all societies hence the significant tie to intercultural conflict.

The term facework refers to the communication strategies that people use to establish, sustain, or restore social identity during interaction (Samp, 2015). Goffman (1959) claims that everyone is concerned about how others perceive them.

Facework varies from culture to culture and influences conflict styles. For example, people from individualistic cultures tend to be more concerned with saving their own face rather than anyone else’s face. This results in a tendency to use more direct conflict management styles. In contrast, people from collectivistic cultures tend to be more concerned with preserving group harmony and saving the other person’s face during conflict by making use of a less direct conversation style to protect others or make them look good.

Conflict Face-Negotiation Theory (Ting-Toomey, 2004) is based on several assumptions about the extent to which face negotiated within a culture and what existing value patterns shape culture of members’ preferences for the process of negotiating face in conflict situations. The Conflict Face-Negotiation Theory is not only influenced by the individual and culture, but also the relationship and the situation of the people experiencing the conflict.

6.5 – Two General Approaches to Managing Conflict

Ways of naming and framing vary across cultural boundaries. People generally deal with conflict in the way that they learned while growing up. For those accustomed to a calm and rational discussion, screaming and yelling may seem to be a dangerous conflict. Yet, conflicts are subject to different interpretations, based on cultural preference, context, and facework ideals.

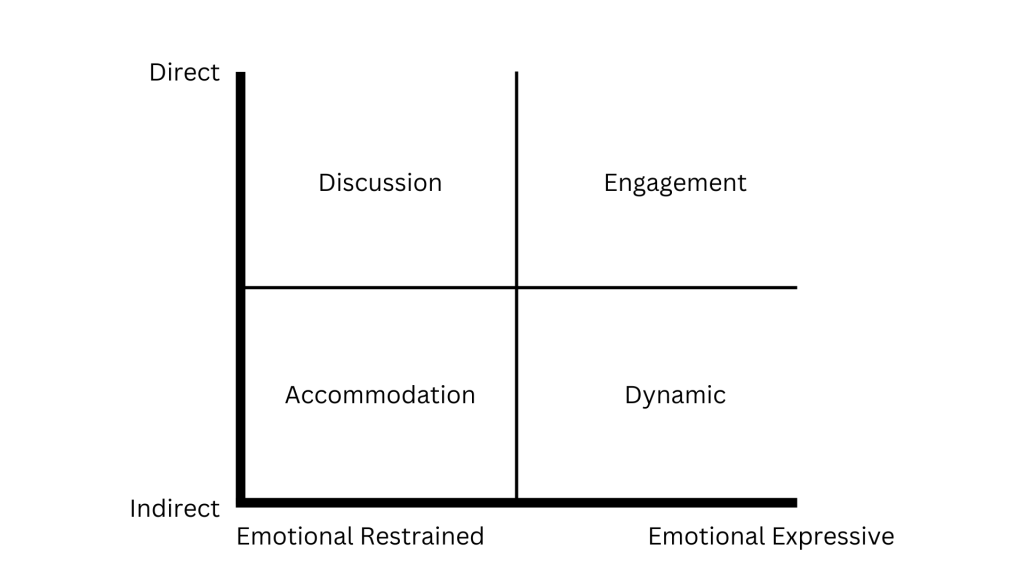

Cultures generally take two general approaches to managing conflict. There is a choice made between directly or indirectly approaching conflict and being emotionally expressive or emotionally restrained.

Direct or Indirect Approach

Direct Approaches are favored by cultures that think conflict is a good thing, and that conflict should be approached directly because working through conflict results in more solid and stronger relationships. This approach emphasizes using precise language, and articulating issues carefully. The best solution is based on solving for set of criteria that has been agreed upon by both parties beforehand.

Indirect Approaches on the other hand are favored by cultures that view conflict as destructive for relationships and prefer to deal with conflict indirectly. These cultures think that when people disagree, they should adapt to the consensus of the group rather than engage in conflict. Confrontations are seen as destructive and ineffective. Silence and avoidance are viewed as effective tools to manage conflict. Intermediaries or mediators are used when conflict negotiation is unavoidable, and people who undermine group harmony may face sanctions or ostracism.

Emotionally Expressive or Emotionally Restrained Approach

Emotionally Expressive people or cultures are those who value intense displays of emotion during disagreement. Outward displays of emotion are seen as indicating that one cares and is committed to resolving the conflict. It is thought that it is better to show emotion through expressive nonverbal behavior and words than to keep feelings inside and hidden from the world. Trust is gained through the sharing of emotions, and sharing is necessary for credibility.

Emotionally Restrained people or cultures are those who think that disagreements are best discussed in an emotionally calm manner. Emotions are controlled through “internalization” and few, if any, verbal or nonverbal expressions will be displayed. A sensitivity to hurting feelings or protecting the face or honor of the other is paramount. Trust is earned through what is seen as emotional maturity, and that maturity is necessary to appear credible.

6.6 – Conflict Styles

Miscommunication and misunderstanding between people within the same culture can feel overwhelming enough, but when this occurs with people of another culture, we may feel a serious sense of stress. Because of this, intercultural conflict experts have developed conflict style inventories based on the two general approaches discussed above. The Intercultural Conflict Style Inventory or ICS (Hammer, 2005), measures people’s approaches to conflict along two different continuums: direct/indirect and expressive/restrained.

Discussion Style

The discussion style combines direct and emotionally restrained dimensions. As it is a verbally direct approach, people who use this style are comfortable expressing disagreements. User perceived strengths of this approach are that it confronts problems, explores arguments, and maintains a calm atmosphere during the conflict. The weaknesses perceived by others is that it is difficult to “read between the lines,” it appears logical but unfeeling, and it can be uncomfortable with emotional arguments. Discussion style can often be found in Northern Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and various co-cultures in the United States.

Engagement Style

The engagement style emphasizes a verbally direct and emotionally expressive approach to dealing with conflict. This style views intense verbal and nonverbal expressions of emotion as demonstrating a willingness to resolve the conflict. User perceived strengths to this approach are that it provides detailed explanations, instructions, and information. This style expresses opinions and shows feelings. The weaknesses perceived by others are the lack of concern with the views and feelings of others along with the potential for dominatingly rude behavior. Individual viewpoints are not separated from emotion. Engagement style is often used in Mediterranean Europe, Russia, Israel, Latin America, and various co-cultures in the United States.

Accommodating Style

The accommodating style combines the indirect and emotionally restrained approaches. People who use this approach may send ambiguous message because they believe that by doing so, the conflict will not get out of control. Silence and avoidance are also considered worthy tools. Strengths to this approach are sensitivity to feelings of the other party, control of emotional outbursts, and consideration to alternative meanings of ambiguous messages. Weaknesses are difficulty in voicing your own opinion, and appearing to be uncommitted or dishonest.

Accommodators tend to avoid direct expression of feelings by using intermediaries, such as friends or relatives who informally act on their behalf when dealing with conflict. Mediation tends to be used in more formal situations when one person believes that conflict will encourage growth in the relationship. Accommodating style is often used in East Asia, North America, and South America.

Dynamic Style

The dynamic style uses indirect communication along with more emotional expressiveness. These people are comfortable with emotions but tend to speak in metaphors and often use mediators. Their credibility is grounded in their degree of emotional expressiveness. User perceived strengths to this approach are using third parties to gather information and resolve conflicts, being skilled at observing nonverbal behaviors, and being comfortable with emotional displays. Weaknesses as perceived by others are appearing too emotional, unreasonable, and possibly devious, while rarely getting to the point. Dynamic style is often used in the Middle East, India, Sub-Saharan Africa, and various co-cultures in the United States.

Caution When Applying the ICS

It is important to recognize that people, and cultures, deal with conflict in a variety of ways for a variety of different reasons. Preferred styles are not static and rigid. People use different conflict styles with different partners. Economic, political, gender, ethnicity, religion, and social issues may all influence how we handle conflict. The ICS is just a guide for the understanding of intercultural conflict.

6.7 – Dealing with Conflict

How people choose to deal with conflict in any given situation depends on the type of conflict and their relationship to the other person. Cognitive conflicts with close friends may be more discussion based in the United States, but more accommodating in Japan. Both are focused on preserving the harmony within the relationship. However, if the cognitive conflict takes place between acquaintances or strangers, where maintaining a relationship is not as important, the engagement or dynamic styles may come out.

Considering all the variations in how people choose to deal with conflict, it’s good to know the different characteristics of each one.

Destructive and Productive

Destructive conflict leads people to make sweeping generalizations about the problem. Groups or individuals escalate the issues with negative attitudes. The conflict starts to deviate from the original issues, and anything in the relationship is open for examination or re-visiting. Participants try to jockey for power while using threats, coercion, and deception as polarization occurs. Leaders display militant, single-minded traits to rally their followers.

Productive conflict features skills that make it possible to manage conflict situations effectively and appropriately. First the participants narrow the conflict to the original issue so that the specific problem is easier to understand. Next, the leaders stress mutually satisfactory outcomes and direct all their efforts to cooperative problem-solving. Research from Alan Sillars and colleagues found that during disputes, individuals selectively remember information that supports themselves and contradicts their partners, view their own communication more positively than their partners’, and blame partners for failure to resolve the conflict (Sillars, Roberts, Leonard, & Dun, 2000). Sillars and colleagues also found that participant thoughts are often locked in simple, unqualified, and negative views. Only in 2% of cases did respondents attribute cooperativeness to their partners and uncooperativeness to themselves (Sillars et al., 2000).

Competitive and Cooperative

Competitive conflict promotes escalation. When conflicts escalate and anger peaks, our minds are filled with negative thoughts of all the grievances and resentments we feel towards others (Sillars et al., 2000). Conflicted parties set up self-reinforcing and mutually confirming expectations. Coercion, deception, suspicion, rigidity, and poor communication are all hallmarks of a competitive atmosphere.

Cooperative conflict promotes perceived similarity, trust, flexibility, and open communication. If both parties are committed to the resolution process, there is a sense of joint ownership in reaching a conclusion.

Because it is very difficult to turn a competitive conflict relationship into a cooperative conflict relationship, a cooperative relationship must be encouraged from the very beginning before the conflict starts to escalate. A cooperative conflict atmosphere promotes perceived similarity, trust, flexibility, and open communication. If both parties are committed to the resolution process, there is a sense of joint ownership in reaching a conclusion.

Consequently, the most important thing you can do to enhance cooperative and productive conflict is to practice critical self-reflection. Business consultants in the United States offer various versions of the Seven-Step Conflict Resolution Model that is a good place to start. The seven steps are:

- State the Problem. Ask each of the conflicting parties to state their view of the problem as simply and clearly as possible.

- Restate the Problem. Ask each party to restate the problem as they understand the other party to view it.

- Understand the Problem. Each party must agree that the other side understands both ways of looking at the problem.

- Pinpoint the Issue. Zero in on the objective facts.

- Ask for Suggestions. Ask how the problem should be solved.

- Make a Plan.

- Follow up.

A quick review of the previous seven steps betrays its western roots with the unspoken assumption that conflicting individuals will be verbally direct and emotionally restrained or advocates of the discussion style of conflict. This model is not effective for use in all cultures and shouldn’t be regarded as such.

6.8 – Cultural Variations and a Culturally Relative Model

The strongest cultural factor that influences your conflict approach is whether you belong to an individualistic or collectivistic culture (Ting-Toomey, 1997), but power distance and context may alsoplay a role in cultural variations of conflict expression.

Individualism and Collectivism

People raised in collectivistic cultures often view direct communication regarding conflict as personal attacks (Nishiyama, 1971), and consequently are more likely to manage conflict through avoidance or accommodation. People from individualistic cultures feel comfortable agreeing to disagree, and don’t particularly see such clashes as personal affronts (Ting-Toomey, 1985). They are more likely to compete, react, or collaborate.

Gudykunst & Kim (2003) suggest that if you are an individualist in a dispute with a collectivist, you should consider the following:

- Recognize that collectivist may prefer to have a third party mediate the conflict so that those in conflict can manage their disagreement without direct confrontation to preserve relational harmony.

- Use more indirect verbal messages.

- Let go of the situation if the other person does not recognize the conflict exists or does not want to deal with it.

If you are a collectivist and are conflicting with someone from an individualist culture, the following guidelines may help:

- Recognize that individualists often separate conflicts from people. It’s not personal.

- Use an assertive style, filled with “I” messages, and be direct by candidly stating your opinions and feelings.

- Manage conflicts even if you’d rather avoid them.

High and Low Power Distance

Conflict within a low power distance culture where people relate to each other as equals, there would be more opportunity to challenge the decision-makers, give in-put, and provide or negotiate an alternative to the conflict. If you are having conflict in a high power distance culture, the power framework of the culture may prevent participation outside of the decision-makers. High power distance cultures may have learned that less powerful people must accept the decisions without comment, even if they have a concern. In this case, conflict resolution must consciously solicit feedback and discussion if equal representation is the desire.

High and Low Context

In high context cultures conflict resolution depends on what is not being said. People involved must be able to infer all the meanings being communicated therefore a higher level of understanding of the culture is required.

In low context cultures messages are explicit and might be presented in more than one way to ensure understanding of what is wanted or expected. People may raise their voices, speak rapidly, express their thoughts in very direct and seemingly rude ways. Less value is placed on nonverbal codes.

One common way to notice the difference between high and low context cultures is the use of the words, yes and no. A member of a high context culture may verbally communicate “yes,” when they are definitely communicating “no” through their nonverbals. Those nonverbals could include context, tone (soft volume), gaze (looking down or away), facial expressions, and the amount of time taken to voice a verbal yes. In a high context culture, a verbal “yes” does not always mean agreement. In a low context culture, a verbal “no” means no.

The Four Skills Approach

Learning to recognize cultural values in actions and behaviors allows communicators to be more effective when negotiating conflict. If the Seven Steps Conflict Resolution Model mentioned above is too ethnocentric, try working with the more ethno-relative Four Skills Approach based on the previously mentioned Conflict Face-Negotiation Theory. These skills are:

- Mindful Listening: Pay special attention to the cultural and personal assumptions being expressed in the conflict interaction. Paraphrase verbal and nonverbal content and emotional meaning of the other party’s message to check for accurate interpretation.

- Mindful Reframing: This is another face-honoring skill that requires the creation of alternative contexts to shape our understanding of the conflict behavior.

- Collaborative Dialogue: An exchange of dialogue that is oriented fully in the present moment and builds on Mindful Listening and Mindful Reframing to practice communicating with different linguistic or contextual resources.

- Culture-based Conflict Resolution Steps is a seven-step conflict resolution model that guides conflicting groups to identify the background of a problem, analyze the cultural assumptions and underlying values of a person in a conflict situation, and promotes ways to achieve harmony and share a common goal.

- What is my cultural and personal assessment of the problem?

- Why did I form this assessment and what is the source of this assessment?

- What are the underlying assumptions or values that drive my assessment?

- How do I know they are relative or valid in this conflict context?

- What reasons might I have for maintaining or changing my underlying conflict premise?

- How should I change my cultural or personal premises into the direction that promotes deeper intercultural understanding?

- How should I flex adaptively on both verbal and nonverbal conflict style levels in order to display facework sensitive behaviors and to facilitate a productive common-interest outcome?

(Ting-Toomey, 2012; Fisher-Yoshida, 2005; Mezirow, 2000)

6.9 – Conclusion

Just as there is no consensus across cultures about what constitutes a conflict or how the conflicting events should be framed, there are also many different conflict response theories. LeBaron, Hammer, Sillars, Gudykunst, Kim, and Ting-Toomey are only a few of the many researchers who have explored the complexities of intercultural conflict. It is also a topic of interest for sociologists, psychologists, business managers, educators, and communities. Acquiring knowledge about personal and intercultural conflict styles can hopefully help us transform our conflicts into meaningful dialogue and become better communicators in the process.

Key Terms

- Conflict

- Conflict of Interest

- Value Conflict

- Tight-Loose Divide

- Face

- Facework

- Expressive/Restrained Approach

- Engagement Style

- Accommodating Style

- Destructive/Productive Conflict

- Seven-Step Conflict Resolution Model

- Affective Conflict

- Cognitive Conflict

- Goal Conflict

- Name-Frame-Blame-Tame

- Conflict-Face Negotiation Theory

- Direct/Indirect Approach

- Intercultural Conflict Style Inventory

- Discussion Style

- Dynamic Style

- Competitive/Cooperative Conflict

- Four Skills Approach

Reflection Questions

- Some of the most severe problems in intercultural relations arise as a consequence of interpersonal conflicts. Consider the following statements. What do they tell us about the potential for intercultural conflict? “The one who raises her/his voice has already lost.” — Japanese proverb “The squeaky wheel gets the grease.” –American proverb

- Traditionally, within the US context, it has been argued that “covert, or hidden, conflict also is destructive in that it leaves issues unresolved and may result in psychological and/or physical estrangement” (Comstock & Buller, 1991, p. 48). Why might this philosophy lead to intercultural conflict?

- What does the following quote mean in terms of intercultural conflict? “Conflicts may be the sources of defeat, lost life, and a limitation of our potentiality, but they may also lead to greater depth of living and the birth or more far-reaching unities, which flourish in the tensions that engender them.” –Karl Jaspers

- Think of an unsolvable intercultural conflict that you have had. Why was it unsolvable? How did you communicate after realizing it was unsolvable? How did the dispute effect your relationship? Looking back on the situation, could you have done anything different to prevent the conflict from becoming unsolvable? If so, what?

- What types of intercultural conflicts occur on our campus? What groups or cultures have frequent conflicts? What irritates you the most about how others handle conflict?

An expressed struggle between at least two interdependent parties who perceive incompatible goals, scare resources, and interference from others in achieving their goals.

Occurs when people become aware that their feelings and emotions are incompatible.

Arises when people disagree about a plan of action or when they have incompatible preferences for a course of action.

A difference in ideologies or values between relational partners.

People become aware that their thought processes or perceptions are in conflict.

When people disagree about a preferred outcome or end state.

Groups with much stronger norms.

Known for creativity and innovation, but they can also be chaotic.

The confusion about how to handle or define the conflict.

Labeling with language and analyzing with language the smaller components parts of an issue.

Labeling with language and analyzing with language the smaller components parts of an issue.

Labeling with language and analyzing with language the smaller components parts of an issue.

Self-image

The communication strategies that people use to establish, sustain, or restore social identity during interaction.

Based several assumptions about the extent to which face negotiated within a culture and what existing value patterns shape culture members’ preferences for the process of negotiating face in conflict situations.

Favored by cultures that think conflict is a good thing, and that conflict should be approached directly, because working through conflict results in more solid and stronger relationships.

Favored by cultures that view conflict as destructive for relationships and prefer to deal with conflict indirectly.

Those who value intense displays of emotion during conversations.

Those who think that disagreements are best discussed in an emotionally calm manner.

Measures people’s approaches to conflict along two different continuums: direct/indirect and expressive/restrained.

Measures people’s approaches to conflict along two different continuums: direct/indirect and expressive/restrained.

Combines direct and emotionally restrained dimensions.

Emphasizes a verbally direct and emotionally expressive approach to dealing with conflict.

Combines the indirect and emotionally restrained approaches.

Uses indirect communication along with more emotional expressiveness.

Leads people to make sweeping generalizations about the problem.

Features skills that make it possible to manage conflict situations effectively and appropriately.

Promotes escalation.

Promotes perceived similarity, trust, flexibility, and open communication.

State the problem, restate the problem, understand the problem, pinpoint the issue, ask for suggestions, make a plan, follow up.

Based on the Conflict Face-Negotiation Theory.

Pay special attention to the cultural and personal assumptions being expressed in the conflict interaction.

This is another face-honoring skill that requires the creation of alternative contexts to shape our understanding of the conflict behavior.

An exchange of dialogue that is oriented fully in the present moment and builds on Mindful Listening and Mindful Reframing to practice communicating with different linguistic or contextual resources.

Seven-step conflict resolution model that guides conflicting groups to identify the background of a problem, analyze the cultural assumptions and underlying values of a person in a conflict situation, and promotes ways to achieve harmony and share a common goal.