Chapter 7 – Relationships

Learning Outcomes

When you have completed this chapter you should be able to do the following:

-

Identify the benefits and challenges of intercultural relationships.

- Understand the foundations of intercultural relationships

- Describe and explain the different types of intercultural relationships

- Describe competent and incompetent relationships

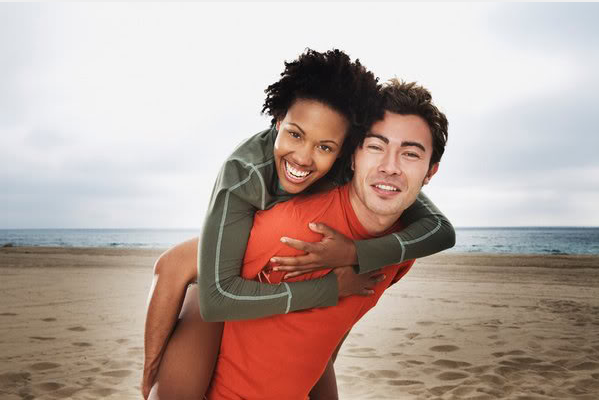

Establishing relationships with people from cultures different than your own can be challenging. How do you get to know them? Should you treat those relationships differently than same culture relationships? Does society influence these new relationships? Learning new customs and traditions can be fun and exciting, but also force us to identify what we think that we know about ourselves along with our prejudices and fears. This chapter will help you gain a better understanding of what to expect when interacting with people that are culturally different from yourself. We will explore the benefits and challenges of intercultural relationships, discuss the different kinds of intercultural relationships, and encourage you with strategies to build solid intercultural relationships.

7.1 – Benefits of Intercultural Relationships

The moment you begin an intercultural relationship, is the moment you begin to learn more about the world. You will start experiencing new foods, listen to new music, learn new games, practice new sports, acquire new words or a new dialect, or read new literature that you might never had access to before. In some ways you gain a new “history” as you learn what it means to belong to a new cultural group.

The difficulties involved in forming, maintaining, or ending an intercultural relationship may help you acquire new skills. According to Docan-Morgan(2015), the skills we develop in all relationships are exaggerated in intercultural relationships. Docan-Morgan postulates that our newfound understanding of another culture will likely make it easier to relate and to feel close to people from many different walks of life. In other words, our intercultural relationships result in new insights and new ways of thinking that we can apply to every relationship.

Intercultural relationships also help us rethink stereotypes we might hold. Martin and Nakayama (2014) point out that the differences we perceive within our intercultural partners tend to be more noticeable in the early stages of the relationship. Because these differences can seem overwhelming, the challenge is to discover the things that both partners have in common and build on those similarities to strengthen the relationship.

7.2 – Challenges of Intercultural Relationships

While intercultural relationships can enrich our lives and provide life-changing benefits, they can also present challenges. First, in order to build a relationship across cultural boundaries, there has to be motivation. Some things about an intercultural relationship will be different than a same culture relationship and take time to explore. It’s much easier to build a relationship where you understand the rules, behaviors, and worldviews of your partner.

Second, intercultural relationships are often characterized by differences. Differences occur in values, perceptions, and communication styles. These differences have been discussed in greater depth in other chapters, but once commonality is established, and the relationship develops, the differences won’t seem to be as insurmountable.

Thirdly, another challenge is dealing with negative stereotypes. Stereotypes are powerful, and often take a conscious effort to detect. Pathstone Mental Health (2017) suggests seven important things we can do to reduce stereotyping and discrimination within relationships.

- Know the facts.

- Be aware of your attitudes and behavior.

- Choose your words carefully.

- Educate others.

- Focus on the positive.

- Support people.

- Include everyone.

Fourth, anxiety or fear about the possible negative consequences because of our actions or being uncertain of how to act towards a person from a different culture is another challenge. Some form of anxiety always exists in the early stages of any relationship but being worried about looking incompetent or offending someone is more pronounced in intercultural relationships. The level of anxiety may even be higher if people have previous negative experiences.

The fifth challenge is affirming another person’s cultural identity. We need to recognize and affirm that the other person might have different values, beliefs, and behaviors which form both their individual and cultural identities. The principle of ethnocentrism encourages a tendency in which we tend to view our own values, beliefs, and behaviors to be the norm and that other cultures should adapt to us.

Sixth, the need for explanations is a huge challenge. Intercultural relationships can be more work than intracultural relationships because of the need for explanations. One must clarify our values, beliefs, and behaviors to ourselves and to each other, not to mention to our families and possibly to our communities. Every difference, and similarity, must be explored. Questions like what a friendship looks like and what are the expectations? Or what does a romantic relationship look like and who must approve the relationship? Do taboos exist within the culture for this kind of relationship?

It’s not impossible for an intercultural relationship to work out. It requires is being open-minded, being interested, being respectful, realizing the similarities, avoiding making assumptions, and celebrating the differences. Intercultural relationships have real challenges, but they can also be amazing.

7.3 – Foundations of Relationships

Every day you meet and interact with new people while going about your daily life, yet few of these people will make a lasting impression. Have you ever wondered what draws you to these special few? It is not a mystery. Based on same-culture research, relational foundation factors include physical attractiveness, similarity, complementarity, proximity, reciprocal liking, and resources (Aron et al., 2008). Newer interculturally focused research being done specifically on intercultural friendship and romantic relationships (Chen, 2006; Sias, et al., 2008) has generated some differences in relational foundations. Both will be explored.

Same Culture Generated Findings on Relational Foundations

It’s not a secret that many people feel drawn to those that they perceive as physically attractive, but we also broaden our idea of attractiveness. Yes, attractiveness can be those stunningly beautiful or stunningly handsome people, but attractiveness can also be what is familiar to us. Most of us do find physical beauty attractive, but we tend to form long-term romantic relationships with people we judge as similar to ourselves in physical attractiveness (Feingold, 1988; White, 1980).

You have probably heard the common saying, “birds of a feather flock together.” This is the same for relationships. Scientific evidence suggests that we are attracted to those we perceive as similar to ourselves (Miller, 2014). One explanation for this is that people we view as similar to ourselves are less likely to cause uncertainty. They seem easier to predict, and we feel more comfortable with them (Berger & Calabrese, 1975). Similarity is more than physical attractiveness through, it means sharing personalities, values, and preferences (Markey & Markey, 2007).

Another common saying that you have probably heard is that “opposites attract.” Complementarity has been debated for a long time, and so far, the research is inconclusive. Based on the 1950s research of sociologist Robert Winch, we would say that we are naturally attracted to people who are different from ourselves, and therefore, somewhat exciting (www.personalitypage.com). It was believed to be a natural quest for completion.

Unfortunately, more current research from Markey & Markey (2007) found the opposite. On the job or with friends, we are not particularly interested in dealing with people who are unlike ourselves. Generally, we are most interested in dealing with people who are like ourselves and don’t display a lot of patience or motivation for dealing with our opposites (Ickes, 1999).

The simple fact of proximity, or often being around each other, exerts far more impact on relationships than generally acknowledged. The idea is that you are more likely to feel attracted to people with whom you have frequent contact with and are less attracted to those with whom you rarely interact.

Another often overlooked relational foundation is reciprocal liking (Aron et al., 2008). The idea is quite simple, we tend to be attracted to people who are attracted to us. Studies examining stories about “falling in love” have found that reciprocal liking is the most commonly mentioned factor leading to love (Riela, Rodriguez, Aron, Xu, and Acevedo, 2010).

And lastly, the final relational foundation is resources. Resources include such qualities as sense of humor, intelligence, kindness, supportiveness, and more (Felmlee et al., 2010). The idea is that you will feel drawn to people that you see as offering benefits (things that you want) with few associated costs (things demanded from you in return) (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978). In other words, you’re attracted to people who can give you what you want and who offer better rewards than others.

Interculturally Focused Research Findings on Relational Foundations

The relational foundations discussed above are still valid and of value in our understanding of intercultural relational foundations. In fact, the various foundations listed above is always the starting point of the interculturally focused research. It’s just that the developmental process of intercultural friendships and romantic relationships contain some unique elements (Chen 2002). Whereas perceived similarity is a key factor in relationship initiation, “difference” is a defining characteristic of an intercultural relationship. Although the partners probably share some similarities, they also have to negotiate these similarities across cultural differences. In other words, maybe both partners like music, but there is a negotiation as to whether house, techno pop, electro swing, and nu disco are all the same and if not, how do they compare from culture to culture.

Recent studies have focused on the conditions necessary for intercultural relationships to develop. Almost all of these studies have focused on international students at colleges and universities. Most of these studies have a small number of student samples. A finding from Australia (Kudo & Simkin, 2003) indicates that a unique relational foundation includes interest in other cultures and empathy as important. Another finding (Lee, 2006) included the creation of a shared identity as being a foundation. In some cases, previous intercultural experience, like studying abroad or living in a diverse place, may motivate someone to pursue intercultural relationships. There are also some findings that speculate that communication may function differently in the context of intercultural relationship development. For example, various cultures may have different conceptualizations of different types of relationships which can cause misunderstandings (Gareis, 2000) or making attempts at categorizing relationship patterns by culture a problem (Chuang, 2003), Collier, 2000, and Collier, et al., 2002).

7.4 – Common Types of Relationships

People are traveling across geographical, national, and cultural boundaries at a quick pace. For many, establishing relationships with persons different from ourselves can be challenging and rewarding.

While communication scholars debate the efficacy of researching intercultural relationships and the problems that might result, the assumption of this book is that relationships do develop, and even a faulty framework is a good place to start. Please remember that each intercultural relationship will differ based on the cultures and people involved. The following is a brief exploration of relationship types and will begin to help you understand the communication aspects of intercultural relationships.

Friendships

Friendship is a unique and important type of interpersonal relationship that constitutes a significant portion of a person’s social life from early childhood all the way through to late adulthood (Rawlins, 1992). Friendship is distinguished from other types of relationships by its “voluntary” nature. In other words, friendship occurs when individuals are relatively free from obligatory ties, duties, and other expectations (Fischer (1975). One can begin or end a friendship as desired.

Notions about friendship are a function of variations in values as well as individualism and collectivism. People who tend to be individualistic often view friendship as a voluntary decision that is more spontaneous and focused on individual goals that might be gained by befriending a particular person. Such goals might include practicing language skills or learning to cook culinary specialties. On the other hand, collectivists may have more obligatory views of friendship. They may see it as a long-term obligation that involves mutual gain such as help with gaining a visa or somewhere to stay during vacations (Wahl & Scholl, 2014).

The idea of what constitutes a friendship certainly varies from culture to culture. In the United States, the term “friend” is a broad term that applies to many different kinds of relationships. In Eastern European countries, for example, the term “friend” is used in a much narrower context. What many cultures in the world consider a “friend,” an American would consider a “close friend” (Martin & Nakayama, 2014). Americans often form relationships quickly, and can come across as informal, forward, intrusive, and superficial (Triandis, 1995). Asian cultures place more emphasis on indirect communication patterns and more stress on maintaining social relationships, sincerity, and spirituality (Barnlund, 1989; Yum, 1988).

Despite the differences in emphasis, research also shows that the overall definition of a close friend is somewhat similar across all cultures. A close friend is thought of as someone who is helpful and nonjudgmental, who you enjoy spending time with but can also be independent, and who shares similar interests and personality traits (Lee, 2006).

Intercultural friendship can be difficult to initiate, develop, and maintain, but that is not to say that different cultures cannot have similar views on friendship. Various cultures can value the same things, such as honesty and trustworthiness, but simply prioritize them differently (Barnlund, 1989). Researchers have found a wide range of important friendship variables such as values, interest, personality traits, network patterns, communication styles, cultural knowledge, relational competence, and intergroup attitudes that impact intercultural friendship formation (Aberson, Shoemaker & Tomolillo, 2004; Collier & Mahoney, 1996; Gareis, 1995; Gudykunst & Nishida, 1979; Mcdermott, 1992; Olanrian, 1996; Yamaguchi & Wiseman, 2003; Zimmermann, 1995).

When friendships cross nationalities, it may be necessary to invest more time in common understanding, due to language barriers. With sufficient motivation and language skills, communication exchanges through self-disclosure can help relationship formation. Research has shown that individuals from different countries in intercultural friendships differ in terms of the topics and depth of self-disclosure, but that as the friendship progresses, self-disclosure increases in depth and breadth (Chen & Nakazawa, 2009).

Further, as people overcome initial challenges to initiating an intercultural friendship, and move toward mutual self-disclosure, the relationship becomes more intimate, which helps friends work through and move beyond their cultural differences to focus on maintaining their relationship. In this sense, intercultural friendships can be just as strong and enduring as other friendships (Lee, 2006).

However, despite self-disclosure being one of the most important factors in the development of close friendships, not much is known about how people communicate and use self-disclosure during the course of developing intercultural friendships, and little has been done to investigate the cultural aspects of self-disclosure. Barnlund (1989) argues that self-disclosure is a western concept and traditional Japanese friendships seldom involve intimate self-disclosure.

Intriguing research from Sias et al. (2008) indicate that cultural differences can enhance, rather than hinder, friendship development. Cultural differences enhanced friendship development because the participants found those differences interesting and exciting. Those who overcame the challenges of language differences were able to develop rich friendships often with a unique vocabulary that included words created from a mixture of both languages. An example of this could be “Spanglish” which is a mixture of Spanish and English or “Chinglish” which is a mixture of Chinese and English. This idiosyncratic language seemed to strengthen the bond between the friends (Sias et al., 2008; Casmir, 1999; Imahori & Cupach, 2005).

Romantic Relationships

There are also similarities and differences between how romantic relationships are perceived in different cultures. When two various cultures come together, there may be significant challenges they have to face, but it is important to remember that like any relationship, intercultural romantic relationships are all different. In general, romantic relationships are “voluntary,” and most cultures stress the importance of openness, mutual involvement, shared nonverbal meanings, and relationship assessment (Martin & Nakayama, 2014).

Individualism and collectivism play a role in romantic relationships as well. In individualistic cultures such as the United States, togetherness is important if it doesn’t interfere too much with one’s individual autonomy. Physical attraction, passion, and love are often initiators of romantic relationships in individualistic cultures. Being open, talking things out, and retaining a sense of self are maintenance strategies.

Collectivistic cultures often value acceptance and “fitting in” as the most important values for romantic partners. Family approval can make or break a romantic relationship in a collectivistic culture. Family members are expected to align with, and support, the dominant values, beliefs, and behavioral expectations of the family hierarchy. Individual happiness is important but thought only to be fully realized within the family system.

Intercultural marriages and romantic relationships are growing at an increasing rate. What once might have seemed unusual, or exotic is becoming more accepted and common place. Although finding an intercultural love relationship might be getting easier but negotiating through the unique challenges inherent to these relationships can still be difficult.

Romantic Relationship Conflict Styles

Romano (2008) found four distinct romantic relationship conflict styles that reflect how intercultural couples negotiate their way through the differences.

- The submission style is the most common and involves one partner abdicating power to the other partner’s culture or cultural preferences. Sometimes the submission style is only seen as a display for the public, whereas the relationship may be more balanced in private. Even though it is the most popular style, this approach rarely works because submission often involves denying certain aspects of one’s own culture.

- Although the compromise style might seem to be the most desirable, it really means that both people must sacrifice some aspect of their life. Each partner gives up some culturally bound habit or value to accommodate the other. Game theorists would call this a lose-lose or no-win situation.

- Some couples will try the obliteration style. In this case, both partners try to erase or obliterate their original cultures and create a new “culture” with new beliefs, values, and behaviors. This can be extremely difficult and create problems with other family members, and this option is only more likely if the couple lives in country that is “home” to neither of them.

- The ideal solution is the consensus style. As it is based on negotiation and mutual agreement, neither person must assume that they must abandon their own culture. This style is related to compromise because of the give-and-take, but it is not a trade-off. Game theorists call this a win-win proposition.

In a survey on intercultural marriages (Prokopchak, 1994), couples were asked to respond about the positives and negatives of intercultural marriage. This survey resulted in four cautions to be considered during intercultural conflict.

- First, know each other’s culture. Don’t think that all families and all cultures operate in a certain way.

- Second, be accountable. There is a tendency not to listen to others. Weigh their concerns.

- Third, know what both cultures value. There is a tendency to value things, but people should be of primary concern.

- And last, identify adaptation versus core value changes. Be aware of the differences between behavior modification or adaptation and core value changes.

Gay and Lesbian Relationships

There has been much more research done on heterosexual or cisgender intercultural friendships and romantic relationships than gay or same-sex intercultural relationships. Romantic relationships are influenced by society and culture, and still today some people face discrimination based on who they love.

Although there are many similarities between gay and cisgender relationships, Martin and Nakayama (2014) believe that such relationships differ in at least four areas. These areas include the importance of close friendships, conflict management, intimacy, and the role of sexuality. Close relationships and friendships might be more important to gays and lesbians who often rely on these ties in the face of social stigma, family ostracism, and discrimination. Researchers Gottman and Levenson (2004) have found some positive differences around conflict management for gay and lesbian couples in the areas of equality and discussion patterns. Hopefully, intercultural researchers will have more to report on this important topic in the future.

7.5 – Communicating in Intercultural Relationships

There are many challenges within intercultural relationships that take time to explain, negotiate, and work through. All relationships are hard work and require constant upkeep to combat the challenges that threaten them. It’s no exaggeration to say that we develop and maintain relationships through communication. Incorrect interpretations of messages can lead to misunderstanding, uncertainty, frustration, and conflict, but the potential rewards include gaining new cultural knowledge, broadening one’s worldview, and breaking stereotypes (Sias et al., 2008).

Types of Intercultural Communication Competence

People who have developed good communication skills are often described as having communication competence. A previous chapter has already explored intercultural communication competence, but researcher Owen Hargie (2011) proposed that there were four levels of intercultural communication competence based on the ideas of competence and incompetent communication as well as conscious or unconscious communication.

Unconsciously incompetent is the “be yourself” approach. This person may not have a strong knowledge of cultural differences and does not see any need to accommodate differences in communication styles or culture. They may not even be aware they are communicating in an incompetent manner.

Once people learn more about culture and communication, they may become consciously incompetent. This is where they have the vocabulary to identify the concepts, and know what they should be doing, but they are not communicating as well as they could. Many of us have experienced the feeling that something isn’t quite right, yet we can’t quite figure out what went wrong.

As our communication skills increase, and our focus is on cultural concepts and communication styles, we become a consciously competent communicator. We know that we are communicating well in the moment, and we can add this memory our growing bank of successful intercultural interactions.

Unconscious competence is the level to achieve. Unconscious competence means that we can communicate successfully without straining to be competent. At this point all the knowledge and previous experiences have been put into practice, and we rarely have to intently focus on our intercultural interactions because it has become second nature. We have developed the skills needed to be competent.

7.6 – Conclusion

This chapter has been focused on the exploration of some common intercultural relationships. It is important to consider intercultural relationships within the societies in which they develop. Because of cultural norms, participants in intercultural relationships must develop unique strategies to appease the “outside world.”

This chapter looked at the benefits and challenges of intercultural relationships along with some cultural patterns to note. We lamented the sparsity of interculturally focused research and wished that there was more available. Hopefully, the take-away is that intercultural relationships can be filled with many kinds of differences and many kinds of similarities. The key to these relationships is often an interesting balance between the two plus the specific people involved.

Key Terms

- Motivation

- Anxiety

- Physical Attractiveness

- Proximity

- Submission

- Consensus

- Conscious Incompetence

- Difference

- Affirming Another Person’s Identity

- Similarity

- Reciprocal Liking

- Compromise

- Turning Point

- Unconscious Incompetence

- Negative stereotypes

- Need for Explanations

- Complementarity

- Resources

- Obliteration

- Conscious Competence

- Unconscious Competence

Reflection Questions

- Many intercultural communication specialists mention open-mindedness as an attribute necessary for the development of successful intercultural relationships. What are some other attributes or ways of thinking that a person should have in order to develop relationships with culturally different people?

-

In thinking about your intercultural relationships or co-cultural relationships, what are the communication strategies that you use to reduce uncertainty when interacting?

-

Nearly 75% of intercultural marriages end in divorce. What might be the reasons? Why would you consider a person from a different culture as a potential romantic partner? If you wouldn’t, why wouldn’t you?

-

Think about the quote, “without others, there is no self.” How do your friends define who you are? Your family? Would an intercultural friend or family member change how you determine the answer to these questions? Why or why not?

-

Same culture relationships rely on the use of smartphones, texting, and social media to maintain the relationships. Can you build and maintain intercultural relationships using the same strategies? What might be the same and what might be different?

Enthusiasm for doing something.

Occur in values, perceptions, and communication styles.

Traits and characteristics negatively attributed to a social group and to its individual members.

Fear about the possible negative consequences because of our actions or being uncertain of how to act towards a person from a different culture is another challenge.

We need to recognize and affirm that the other person might have different values, beliefs, and behaviors which form both their individual and cultural identities.

Tendency to think that our own culture is superior to other cultures.

One must clarify our values, beliefs, and behaviors to ourselves and to each other, not to mention to our families and possibly to our communities.

The degree to which a person’s physical features are considered aesthetically pleasing or beautiful.

Sharing personalities, values, and preferences.

Opposites attract.

Often being around each other.

Attracted to people who are attracted to us.

You’re attracted to people who can give you what you want and who offer better rewards than others.

Unique and important type of interpersonal relationship that constitutes a significant portion of a person’s social life from early childhood all the way through to late adulthood.

Are “voluntary,” and most cultures stress the importance of openness, mutual involvement, shared nonverbal meanings, and relationship assessment.

Cultures that put more emphasis on the importance of relationships, loyalty, and working together.

Reflect how intercultural couples negotiate their way through differences.

Involves one partner abdicating power to the other partner’s culture or cultural preferences.

Both people must sacrifice some aspect of their life.

Both partners try to erase or obliterate their original cultures and create a new “culture” with new beliefs, values, and behaviors.

Based on negotiation and mutual agreement, neither person must assume that they must abandon their own culture.

People who have developed good and effective communication skills.

The “be yourself” approach.

People have the vocabulary to identify the concepts, and know what they should be doing, but they are not communicating as well as they could.

As our communication skills increase, and our focus is on cultural concepts and communication styles.

We can communicate successfully without straining to be competent.