4.3 Personality, Values, and Attitudes in the Workplace

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Compare and contrast personality tests based on trait theories.

- Apply personality traits, values, and attitudes to workplace experiences.

Brad works for a marketing firm in Kansas City, Missouri. He has worked for the company for over 15 years and is very talented at his job. He has recently been promoted and now runs the marketing team for a number of the company’s largest clients. Brad is a very direct individual, and is extremely comfortable giving feedback, even unsolicited. During every team meeting, Brad is quick to shut down ideas and is known for giving harsh, personal feedback during his teams’ presentations. Although he is one of the most tenured, no one goes to him for help or advice because they fear he will use it as an opportunity to point out every professional and personal flaw (Figure 4.8).

Since Brad was promoted to leading the marketing team, employee morale and productivity have dropped significantly. Is this a matter of clashing personalities? Or is Brad too abrasive and brutal in his communication style and feedback techniques?

Personality traits play a role in every relationship. Individual personalities help to form an organization’s culture and image. Therefore, every successful organization relies heavily on the personality traits of its employees. While everyone has a different personality, there are certain traits and characteristics that are common amongst individuals. Understanding these similarities and differences can help you to better understand your coworkers, your team, and even your supervisors and bosses.

It is also important to make a connection between personalities and behavior. Certain personality traits can be used to predict behavior. This is why smart hiring practices are so important. It is equally, if not more, important to hire based on behavioral based interview questions and personality questionnaires as opposed to hiring solely on previous experience. Being aware of how personality traits influence behavior can be extremely beneficial to your success in the workplace. This section will deep dive into the idiosyncrasies of personality traits and how certain ones can negatively or positively impact an organization.

Recognizing your personality traits is the first step in successfully achieving your goals. Being able to capitalize on your strengths and also understanding how to strengthen your weaknesses is the cornerstone of success. When we use our personality to make decisions best suited for ourselves, we are more likely to find long-lasting happiness and satisfaction. Similarly, understanding the personalities of others will help us to form stronger relationships.

Personality Traits

In some ways, finding someone with differing personality traits can be beneficial. Relationships involving individuals with opposite personalities can challenge each person to view situations from a different perspective. In the workplace, differing personality traits are important to creating a diverse workplace where creativity and varying ideas can thrive. At the same time, it is also important to surround yourself with people who have similar core beliefs, values, and goals. Hiring employees while taking their personality into consideration can help foster an inclusive and positive work environment.

Thousands of personality traits have been identified over the years. It would be nearly impossible to find an effective way to identify each and every one of an individual’s personality traits. To help streamline the process, multiple types of personality tests are available to help individuals recognize their strengths, preferences, communication style, among many other important characteristics. Let’s look into some of the most popular personality tests used today.

16PF Questionnaire

Trait theorists believe personality can be understood via the approach that all people have certain traits, or characteristic ways of behaving. Do you tend to be sociable or shy? Passive or aggressive? Optimistic or pessimistic? Moody or even-tempered? Early trait theorists tried to describe all human personality traits. For example, one trait theorist, Gordon Allport (Allport & Odbert, 1936), found 4,500 words in the English language that could describe people. He organized these personality traits into three categories: cardinal traits, central traits, and secondary traits. A cardinal trait is one that dominates your entire personality, and hence your life—such as Ebenezer Scrooge’s greed and Mother Theresa’s altruism. Cardinal traits are not very common: Few people have personalities dominated by a single trait. Instead, our personalities typically are composed of multiple traits. Central traits are those that make up our personalities (such as loyal, kind, agreeable, friendly, sneaky, wild, and grouchy). Secondary traits are those that are not quite as obvious or as consistent as central traits. They are present under specific circumstances and include preferences and attitudes. For example, one person gets angry when people try to tickle him; another can only sleep on the left side of the bed; and yet another always orders her salad dressing on the side. And you—although not normally an anxious person—feel nervous before making a speech in front of your English class.

In an effort to make the list of traits more manageable, Raymond Cattell (1946, 1957) narrowed down the list to about 171 traits. However, saying that a trait is either present or absent does not accurately reflect a person’s uniqueness, because all of our personalities are actually made up of the same traits; we differ only in the degree to which each trait is expressed. Cattell (1957) identified 16 factors or dimensions of personality: warmth, reasoning, emotional stability, dominance, liveliness, rule-consciousness, social boldness, sensitivity, vigilance, abstractedness, privateness, apprehension, openness to change, self-reliance, perfectionism, and tension (see Table 2.1 Personality Factors Measured by the 16PF Questionnaire below). He developed a personality assessment based on these 16 factors, called the 16PF. Instead of a trait being present or absent, each dimension is scored over a continuum, from high to low. For example, your level of warmth describes how warm, caring, and nice to others you are. If you score low on this index, you tend to be more distant and cold. A high score on this index signifies you are supportive and comforting.

| Factor | Low Score | High Score |

|---|---|---|

| Warmth | reserved, detached | outgoing, supportive |

| Intellect | concrete thinking | analytical |

| Emotional Stability | moody, irritable | stable, calm |

| Aggressiveness | docile, submissive | controlling, dominant |

| Liveliness | somber, prudent | adventurous, spontaneous |

| Dutifulness | unreliable | conscientious |

| Social Assertiveness | shy, restrained | uninhibited, bold |

| Sensitivity | tough-minded | sensitive, caring |

| Paranoia | trusting | suspicious |

| Abstractness | conventional | imaginative |

| Introversion | open, straightforward | private, shrewd |

| Anxiety | confident | apprehensive |

| Openmindedness | closeminded, traditional | curious, experimental |

| Independence | outgoing, social | self-sufficient |

| Perfectionism | disorganized, casual | organized, precise |

| Tension | relaxed | stressed |

The Five Factor Model

The Five Factor Model, with its five factors referred to as the Big Five personality factors, is the most popular theory in personality psychology today and the most accurate approximation of the basic personality dimensions (Funder, 2001). The five factors are openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. A helpful way to remember the factors is by using the mnemonic OCEAN.

In the Five Factor Model, each person possesses each factor, but they occur along a spectrum (Figure 4.9). Openness to experience is characterized by imagination, feelings, actions, and ideas. People who score high on this factor tend to be curious and have a wide range of interests. Conscientiousness is characterized by competence, self-discipline, thoughtfulness, and achievement-striving (goal-directed behavior). People who score high on this factor are hardworking and dependable. Numerous studies have found a positive correlation between conscientiousness and academic success (Akomolafe, 2013; Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2008; Conrad & Patry, 2012; Noftle & Robins, 2007; Wagerman & Funder, 2007). Extroversion is characterized by sociability, assertiveness, excitement-seeking, and emotional expression. People who score high on this factor are usually described as outgoing and warm. Not surprisingly, people who score high on both extroversion and openness are more likely to participate in adventure and risky sports due to their curious and excitement-seeking nature (Tok, 2011). The fourth factor is agreeableness, which is the tendency to be pleasant, cooperative, trustworthy, and good-natured. People who score low on agreeableness tend to be described as rude and uncooperative, yet one recent study reported that men who scored low on this factor actually earned more money than men who were considered more agreeable (Judge, Livingston, & Hurst, 2012). The last of the Big Five factors is neuroticism, which is the tendency to experience negative emotions. People high on neuroticism tend to experience emotional instability and are characterized as angry, impulsive, and hostile. Watson and Clark (1984) found that people reporting high levels of neuroticism also tend to report feeling anxious and unhappy. In contrast, people who score low in neuroticism tend to be calm and even-tempered.

The Big Five personality factors each represent a range between two extremes. In reality, most of us tend to lie somewhere midway along the continuum of each factor, rather than at polar ends. It’s important to note that the Big Five factors are relatively stable over our lifespan, with some tendency for the factors to increase or decrease slightly. Researchers have found that conscientiousness increases through young adulthood into middle age, as we become better able to manage our personal relationships and careers (Donnellan & Lucas, 2008). Agreeableness also increases with age, peaking between 50 to 70 years (Terracciano, McCrae, Brant, & Costa, 2005). Neuroticism and extroversion tend to decline slightly with age (Donnellan & Lucas; Terracciano et al.). Additionally, The Big Five factors have been shown to exist across ethnicities, cultures, and ages, and may have substantial biological and genetic components (Jang, Livesley, & Vernon, 1996; Jang et al., 2006; McCrae & Costa, 1997; Schmitt et al., 2007).

The HEXACO Model

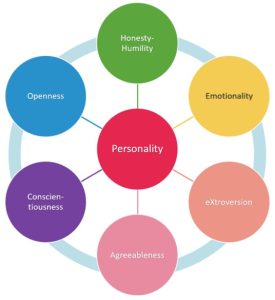

Another model of personality traits is the HEXACO model. HEXACO is an acronym for six broad traits: honesty-humility, emotionality, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience (Anglim & O’Connor, 2018) (Figure 4.10).

Table 4.2 HEXACO Traits below, provides a brief overview of each trait. This model is similar to the Big Five, but it posits slightly different versions of some of the traits, and its proponents argue that one important class of individual differences was omitted from the Five-Factor Model. The HEXACO adds Honesty-Humility as a sixth dimension of personality. People high in this trait are sincere, fair, and modest, whereas those low in the trait are manipulative, narcissistic, and self-centered. Thus, trait theorists are agreed that personality traits are important in understanding behavior, but there are still debates on the exact number and composition of the traits that are most important.

| Trait | Example Aspects of Trait |

|---|---|

| Honesty-humility | sincerity, modesty, faithfulness |

| Emotionality | sentimentality, anxiety, sensitivity |

| Extraversion |

sociability, talkativeness, boldness |

| Agreeableness | patience, tolerance, gentleness |

| Conscientiousness | organization, thoroughness, precision |

| Openness | creativity, inquisitiveness, innovativeness |

Personality tests are used to help companies better understand their employees or employee candidates. It is important to remember that there are thousands of different personality traits. Each individual has their own unique set and combination of personality traits. While each of the personality tests we discussed in this section are effective in their own right, there is no exact science to identifying each and every personality trait present in an individual. In addition, many personality tests are based upon an individual’s self-assessment and results may differ from day to day. Personality tests may help to confirm things you already believed to be true or they may open your eyes to a side of yourself you didn’t realize existed. Let’s move onto the next section to examine how an individual’s personality can help to predict their choices and behavior.

Personality and Behavior

As we discussed in the last section, personality traits do not fall under a one-size-fits-all category. Every individual has their own unique personality that helps to form their outlook on life and shapes their interactions with others. Imagine being able to take an individual’s personality fingerprint and predict how they would act in any given scenario. While seeing into the future is impossible, using personality traits to predict an individual’s behavior is on the spectrum of possibilities.

Personalities have been studied and discussed dating back to Ancient Greece and Roman times. Research has been conducted for years and years to try to determine how to properly predict behavior using an individual’s personality traits. However, in the 1970s, after years of research and testing, psychologists Daryl Bem and Walter Mischel had limited success in making consistently successful predictions (McAndrew, 2018). Their frustrations led them to believe that situational factors and stressors were more responsible for decisions than an individual’s personality.

So which is it? Is it personality or the situation that plays a leading role in influencing a person’s behavior? The short answer is both. Many people expect a clear-cut answer to the question. However, that is an impossible task when it comes to predicting behavior. It is important to take into account the individual’s personality in addition to the situation they find themselves in. The next section will discuss how situations can influence behavior, but for the purpose of this section, let’s explore the benefits and limitations of using personality to predict behavior.

Personality traits are all on a spectrum. The more extreme an individual is on the spectrum, the easier it is to predict their behavior. Since many personality tests focus on broad traits (OCEAN for example), there is a wide range for interpretation. Let’s look at introverts versus extraverts as an example. Everyone falls somewhere on the introvert vs. extravert scale. Even if you are more of an extravert than an introvert you may still not be considered a very outgoing person. Depending on the group of individuals you find yourself with may also change others’ perception of you. For example, if you are surrounded by extremely extraverted people, you may appear to be introverted, even though you consider yourself an extravert. Similar to weight or height, everyone has a measurement unique to them but it may appear to be higher or lower when compared to that of others. According to McAndrew (2018), “Research has shown that the more to one of the extremes a person falls on a trait, the more consistently the trait will be a factor in his or her behavior.”

It is also important to take into consideration that observing personality traits in multiple scenarios can be more accurate in predicting behavior. Trying to make a prediction based on a single interaction does not paint a completely accurate picture of an individual. Being able to observe the varying degrees of an individual’s personality can help to better understand a person and determine the best way to maximize their strengths and support their weaknesses.

So how is predicting behavior helpful in the workplace? Using personality traits to form workgroups and teams can be extremely beneficial in the long run. Diversity is important to success. At the same time, pairing together like-minded individuals can help to promote efficiency and collaboration. Using personality traits and tests to form teams can help to bring together a beautifully balanced group. It is important to keep in mind; however, that observing an individual’s personality multiple times may provide additional insight into how they operate. It is extremely important to utilize new found information and observations to rearrange team dynamics. Personality traits alone cannot successfully predict behavior. Situations also play an important role in determining how an individual will act.

Situational Influences on Personality

Certain situations and circumstances can influence a person’s day in a positive or negative way. Depending on the circumstance, a normally positive person may become more negative. On the other hand, a traditionally pessimistic person may appear to be more positive. So how is this possible? You have experienced both triumphs and tribulations in your lifetime and whether or not you realized it, they most likely impacted the way you acted and altered your personality for that period of time. It is human nature for emotions and personalities to differ depending on what is happening in our lives.

Even if we are not aware of what others may be going through, it is reasonable to assume that certain situations in the lives of all individuals impacts their personality. For example, you are out with friends, and you see your friend Lorenzo, who is the most extroverted person in the group, crying in the corner. Does this mean Lorenzo is no longer an extravert but rather an introvert? Or could he be crying because he just heard some upsetting news? Chances are, the latter option is a more realistic one. While the news may have changed his personality during that social setting on that day, it most likely did not alter it permanently.

Let’s look at another example. The coworker you disagree with most, Kayla, who constantly argues against your ideas, comes into work Monday morning with a pep in her step. At your team meeting, she completely supports your proposed project idea and offers to help execute it. Has Kayla turned a corner and has decided to end the feud between you two? Possibly. But odds are there is something in her life that has temporarily altered her personality. What you may not know, is that over the weekend her all time favorite team won the Super Bowl. Her excitement from the day before spilled over into Monday, presenting a much version of Kayla that seems to like you a great deal more.

These are just two small examples of how situations in people’s lives can alter the way they act. People can also change their personality based on who they’re around. If the person you’re with makes you uncomfortable, you’re not likely to be very talkative and offer up good conversation. However, if you’re on the phone with a friend you haven’t talked to for awhile, you’re likely to have an animated conversation.

If situations can influence personality and personality can predict behavior, then situational influences also contribute to predicting behavior. It also brings into question whether or not personality traits are consistent since they are easily influenced by situations. In 1968, Walter Mischel published a book entitled Personality & Assessment. In his book, Mischel argued that an interactionist approach was best suited when exploring personality, situations, and behavior. This interactionist approach believes that both personality and situational circumstances create behavior. In addition, Mischel explained that personalities tend to differ across a range of situations (personality at work versus home); however, they keep consistencies within similar situations (work meetings). This revelation created an upset in the traditional view of personality by arguing that personality stability and instability can each exist at the same time.

Values

Values refer to stable life goals that people have, reflecting what is most important to them. Values are established throughout one’s life as a result of the accumulating life experiences and tend to be relatively stable (Lusk & Oliver, 1974; Rokeach, 1973). The values that are important to people tend to affect the types of decisions they make, how they perceive their environment, and their actual behaviors. Moreover, people are more likely to accept job offers when the company possesses the values people care about (Judge & Bretz, 1992; Ravlin & Meglino, 1987). Value attainment is one reason why people stay in a company, and when an organization does not help them attain their values, they are more likely to decide to leave if they are dissatisfied with the job itself (George & Jones, 1996).

What are the values people care about? There are many typologies of values. One of the most established surveys to assess individual values is the Rokeach Value Survey (Rokeach, 1973). This survey lists 18 terminal and 18 instrumental values in alphabetical order. Terminal values refer to end states people desire in life, such as leading a prosperous life and a world at peace. Instrumental values deal with views on acceptable modes of conduct, such as being honest and ethical, and being ambitious.

According to Rokeach, values are arranged in hierarchical fashion. In other words, an accurate way of assessing someone’s values is to ask them to rank the 36 values in order of importance. By comparing these values, people develop a sense of which value can be sacrificed to achieve the other, and the individual priority of each value emerges.

Where do values come from? Research indicates that they are shaped early in life and show stability over the course of a lifetime. Early family experiences are important influences over the dominant values. People who were raised in families with low socioeconomic status and those who experienced restrictive parenting often display conformity values when they are adults, while those who were raised by parents who were cold toward their children would likely value and desire security (Kasser, Koestner, & Lekes, 2002).

Values of a generation also change and evolve in response to the historical context that the generation grows up in. Research comparing the values of different generations resulted in interesting findings. For example, Generation Xers (those born between the mid-1960s and early 1980s) are more individualistic and are interested in working toward organizational goals so long as they coincide with their personal goals. This group, compared to the baby boomers (born between the 1940s and 1960s), is also less likely to see work as central to their life and more likely to desire a quick promotion (Smola & Sutton, 2002).

Values a person holds will affect their employment. For example, someone who values stimulation highly may seek jobs that involve fast action and high risk, such as firefighter, police officer, or emergency medicine. Someone who values achievement highly may be likely to become an entrepreneur or intrapreneur. And an individual who values benevolence and universalism may seek work in the nonprofit sector with a charitable organization or in a “helping profession,” such as nursing or social work. Like personality, values have implications for Organizing activities, such as assigning duties to specific jobs or developing the chain of command; employee values are likely to affect how employees respond to changes in the characteristics of their jobs.

In terms of work behaviors, a person is more likely to accept a job offer when the company possesses the values he or she cares about. A firm’s values are often described in the company’s mission and vision statements, an element of the Planning function (Judge & Bretz, 1992; Ravlin & Meglino, 1987). Value attainment is one reason people stay in a company. When a job does not help them attain their values, they are likely to decide to leave if they are also dissatisfied with the job (George & Jones, 1996). Therefore, understanding employees at work requires understanding the value orientations of employees.

We often find ourselves in situations where our values do not coincide with someone we are working with. For example, if Alison’s main value is connection, this may come out in a warm communication style with coworkers and an interest in their personal lives. Imagine Alison works with Tyler, whose core value is efficiency. Because of Tyler’s focus, he may find it a waste of time to make small talk with colleagues. When Alison approaches Tyler and asks about his weekend, she may feel offended or upset when he brushes her off to ask about the project they are working on together. She feels like a connection wasn’t made, and he feels like she isn’t efficient. Understanding our own values as well as the values of others can greatly help us become better communicators.

Attitudes

Our attitudes are favorable or unfavorable opinions toward people, things, or situations. Many things affect our attitudes, including the environment we were brought up in and our individual experiences. Our personalities and values play a large role in our attitudes as well. For example, many people may have attitudes toward politics that are similar to their parents, but their attitudes may change as they gain more experiences. If someone has a bad experience around the ocean, they may develop a negative attitude around beach activities. However, assume that person has a memorable experience seeing sea lions at the beach, for example, then he or she may change their opinion about the ocean. Likewise, someone may have loved the ocean, but if they have a scary experience, such as nearly drowning, they may change their attitude.

The important thing to remember about attitudes is that they can change over time, but usually some sort of positive experience needs to occur for our attitudes to change dramatically for the better. We also have control of our attitude in our thoughts. If we constantly stream negative thoughts, it is likely we may become a negative person.

In a workplace environment, you can see where attitude is important. Someone’s personality may be cheerful and upbeat. These are the prized employees because they help bring positive perspective to the workplace. Likewise, someone with a negative attitude is usually someone that most people prefer not to work with. The problem with a negative attitude is that it has a devastating effect on everyone else. Have you ever felt really happy after a great day and when you got home, your roommate was in a terrible mood because of her bad day? In this situation, you can almost feel yourself deflating! This is why having a positive attitude is a key component to having good human relations at work and in our personal lives.

Our attitude is ultimately about how we set our expectations; how we handle the situation when our expectations are not met; and finally, how we sum up an experience, person, or situation. When we focus on improving our attitude on a daily basis, we get used to thinking positively and our entire personality can change. It goes without saying that employers prefer to hire and promote someone with a positive attitude as opposed to a negative one. Davis (2019) suggests four ways to develop a more positive attitude:

-

- Spending more time thinking about positive thing will help strengthen the positive neural pathways in your brain. This can help you generate your own positive thoughts and feelings more easily.

- Find a silver lining even with things you perceive to be negative. Is there something you can learn or take away from it? Look for an alternative perspective that can help you view the situation more positively.

- Engaging in random acts of kindness can improve your attitude. When you help others unprompted and without reward, you can develop a positive sense of self and the gratitude expressed by those you help will help create positive feelings.

- Smile, laugh, and enjoy life more. This one might seem like a struggle at times, but the more you can appreciate the small things in your life, the more positive your attitude can become.

When considering our personality, values, and attitudes, we can begin to get the bigger picture of who we are and how our experiences affect how we behave at work and in our personal lives. It is a good idea to reflect often on what aspects of our personality are working well and which we might like to change. With self-awareness we can make changes that eventually result in better human relations.

Summary

- Cattell developed a personality assessment called the 16PF.

- The Five Factor Model is the most widely accepted trait theory today. The five factors are openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. These factors occur along a continuum.

- The HEXACO Model posits slightly different versions of some of the Big Five traits, and its proponents argue that one important class of individual differences was omitted from the Five-Factor Model.

- Personality tests are used to help companies better understand their employees or employee candidates.

- Values express a person’s life goals; they are similar to personality traits in that they are relatively stable over time.

- In the workplace, a person is more likely to accept a job that provides opportunities for value attainment. People are also more likely to remain in a job and career that satisfy their values.

- Our personality can help define our attitudes toward specific things, situations, or people. Most people prefer to work with people who have a positive attitude.

- We can improve our attitude by waking up and believing that the day is going to be great. We can also keep awareness of our negative thoughts or those things that may prevent us from having a good day. Spending time with positive people can help improve our own attitude as well.

Discussion Questions

- Choose one of the personality assessments discussed in this section. Can you think of jobs or occupations that seem particularly suited to each trait? Which traits would be universally desirable across all jobs?

- Why might a prospective employer screen applicants using personality assessments?

- Have you ever held a job where your personality did not match the demands of the job? How did you react to this situation? How were your attitudes and behaviors affected?

Remix/Revisions featured in this section

- Small editing revisions to tailor the content to the Psychology of Human Relations course.

- Changed formatting for photos to provide links to locations of images and CC licenses.

- Added doi links to references to comply with APA 7th edition formatting reference manual.

- Remix of introduction, behavior, and situational influences from Why It Matters: Individual Personalities and Behaviors (Organizational Behavior – Lumen Learning) , trait theories from 11.7 Trait Theories (Psychology 2e – Openstax), values from 2.3 Personality and Values (Principles of Management – University of Minnesota) attitudes from 1.2 Human Relations: Personality and Attitude Effects (Saylor Academy).

Attributions

CC Licensed Content, Original

Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Stevy Scarbrough. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Human Relations. Authored by: Saylor Academy. Located at: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_human-relations/s05-02-human-relations-personality-an.html License: CC-BY-NC-SA

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

An Introduction to Organizational Behavior. Authored by: Talya Bauer and Berrin Erdogan. Publisher: Unnamed Publisher. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-organizationalbehavior/ License: CC-BY-NC-SA

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Organizational Behavior and Human Relations. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group, Barbara Egel, and Rebert Danielson. Publisher: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-organizationalbehavior/ License: CC-BY

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Principles of Management. Authored by: University of Minnesota. Located at: https://open.lib.umn.edu/principlesmanagement/chapter/2-3-personality-and-values-3/ License: CC-BY-NC-SA

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Psychology 2e. Authored by: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett. Publisher: Openstax. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/11-7-trait-theorists License: CC-BY

References

Akomolafe, M. J. (2013). Personality characteristics as predictors of academic performance of secondary school students. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(2), 657–664.

Anglim, J., & O’Connor, P. (2018). Measurement and research using Big Five, HEXACO, and narrow traits: A primer for researchers and practitioners. Australian Journal of Psychology, 71(1), 16–25. https://aps.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ajpy.12202

Cattell, R. B. (1946). The description and measurement of personality. Harcourt, Brace, & World.

Cattell, R. B. (1957). Personality and motivation structure and measurement. World Book.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2008). Personality, intelligence, and approaches to learning as predictors of academic performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 1596–1603. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.paid.2008.01.003

Conrad, N. & Patry, M.W. (2012). Conscientiousness and academic performance: A Mediational Analysis. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2012.060108

Davis, T. (2019, September 23). Four simple ways to develop a more positive attitude: How to think, feel, and act a bit more positive. Psychology Today, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/click-here-happiness/201909/four-simple-ways-develop-more-positive-attitude

Donnellan, M. B., & Lucas, R. E. (2008). Age differences in the big five across the life span: Evidence from two national samples. Psychology and Aging, 23(3), 558–566. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0012897

Funder, D. C. (2001). Personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 197–221. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.197

George, J. M., & Jones, G. R. (1996). The experience of work and turnover intentions: Interactive effects of value attainment, job satisfaction, and positive mood. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 318–325. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-9010.81.3.318

Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. J., & Vernon, P. A. (1996). Heritability of the big five personality dimensions and their facts: A twin study. Journal of Personality, 64(3), 577–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00522.x

Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. J., Ando, J., Yamagata, S., Suzuki, A., Angleitner, A., et al. (2006). Behavioral genetics of the higher-order factors of the Big Five. Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.033

Judge, T. A., & Bretz, R. D. (1992). Effects of work values on job choice decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 261–271. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-9010.77.3.261

Judge, T. A., Livingston, B. A., & Hurst, C. (2012). Do nice guys-and gals- really finish last? The joint effects of sex and agreeableness on income. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(2), 390–407. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0026021

Kasser, T., Koestner, R., & Lekes, N. (2002). Early family experiences and adult values: A 26-year, prospective longitudinal study. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(6), 826–835. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1177/0146167202289011

Lusk, E. J., & Oliver, B. L. (1974). Research notes. American manager’s personal value systems-revisited. Academy of Management Journal, 17 (3), 549–554. https://doi.org/10.2307/254656

McAndrew, F. T. (2018, October 2) “When Do Personality Traits Predict Behavior?” Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/out-the-ooze/201810/when-do-personality-traits-predict-behavior.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist, 52(5), 509–516. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.52.5.509

Mischel, W. (1968). Personality and Assessment. New York, NY: Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Noftle, E. E., & Robins, R. W. (2007). Personality predictors of academic outcomes: Big Five correlates of GPA and SAT scores. Personality Processes and Individual Differences, 93, 116–130. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.116

Ravlin, E. C., & Meglino, B. M. (1987). Effect of values on perception and decision making: A study of alternative work values measures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 666–673. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-9010.72.4.666

Rokeach, M. (1973). The Nature of Human Values. New York: Free Press.

Schmitt, D. P., Allik, J., McCrae, R. R., & Benet-Martinez, V. (2007). The geographic distribution of Big Five personality traits: Patterns and profiles of human self-description across 56 nations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38, 173–212. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022022106297299

Smola, K. W., & Sutton, C. D. (2002). Generational differences: Revisiting generational work values for the new millennium. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 363–382. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1002/job.147

Terracciano A., McCrae R. R., Brant L. J., Costa P. T., Jr. (2005). Hierarchical linear modeling analyses of the NEO-PI-R scales in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Psychology and Aging, 20, 493–506. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.493

Tok, S. (2011). The big five personality traits and risky sport participation. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 39(8), 1105–1111. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2011.39.8.1105

Wagerman, S. A., & Funder, D. C. (2007). Acquaintance reports of personality and academic achievement: A case for conscientiousness. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 221–229. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.001

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 465–490. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.96.3.465