9.3 Teamwork and Conflict in the Workplace

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the five stages of team development.

- Describe different positive and negative team roles.

- Describe strategies for cultivating a positive group climate.

- Describe common types and causes of conflict that arise within teams.

Group dynamics involve the interactions and processes of a team and influence the degree to which members feel a part of the goal and mission. A team with a strong identity can prove to be a powerful force. One that exerts too much control over individual members, however, runs the risk or reducing creative interactions, resulting in tunnel vision. A team that exerts too little control, neglecting all concern for process and areas of specific responsibility, may go nowhere. Striking a balance between motivation and encouragement is key to maximizing group productivity.

A skilled communicator creates a positive team by first selecting members based on their areas of skill and expertise. Attention to each member’s style of communication also ensures the team’s smooth operation. If their talents are essential, introverts who prefer working alone may need additional encouragement to participate. Extroverts may need encouragement to listen to others and not dominate the conversation. Both are necessary, however, so the selecting for a diverse group of team members deserves serious consideration.

Stages of Team Development

For teams to be effective, the people in the team must be able to work together to contribute collectively to team outcomes. But this does not happen automatically: it develops as the team works together. You have probably had an experience when you have been put on a team to work on a school assignment or project. When your team first gets together, you likely sit around and look at each other, not knowing how to begin. Initially you are not a team; you are just individuals assigned to work together. Over time you get to know each other, to know what to expect from each other, to know how to divide the labor and assign tasks, and to know how you will coordinate your work. Through this process, you begin to operate as a team instead of a collection of individuals.

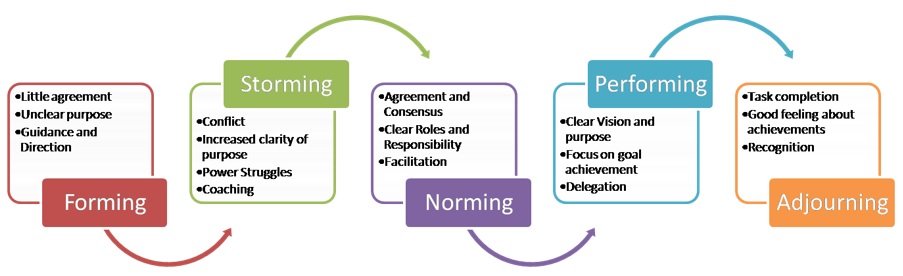

This process of learning to work together effectively is known as team development. Research has shown that teams go through definitive stages during development. Tuckman (1965) identified a five-stage development process that most teams follow to become high performing. He called the stages: forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning (Figure 9.7)

Forming stage

The forming stage involves a period of orientation and getting acquainted (Figure 9.8). Uncertainty is high during this stage, and people are looking for leadership and authority. A member who asserts authority or is knowledgeable may be expected to take control. Team members are asking such questions as “What does the team offer me?” “What is expected of me?” “Will I fit in?” Most interactions are social as members get to know each other.

Storming stage

The storming stage is the most difficult and critical stage to pass through. It is a period marked by conflict and competition as individual personalities emerge. Team performance may actually decrease in this stage because energy is put into unproductive activities. Members may disagree on team goals, and subgroups and cliques may form around strong personalities or areas of agreement. To get through this stage, members must work to overcome obstacles, to accept individual differences, and to work through conflicting ideas on team tasks and goals. Teams can get bogged down in this stage. Failure to address conflicts may result in long-term problems.

Norming stage

If teams get through the storming stage, conflict is resolved and some degree of unity emerges. In the norming stage, consensus develops around who the leader or leaders are, and individual member’s roles. Interpersonal differences begin to be resolved, and a sense of cohesion and unity emerges (Figure 9.9). Team performance increases during this stage as members learn to cooperate and begin to focus on team goals. However, the harmony is precarious, and if disagreements re-emerge the team can revert to storming.

Performing stage

In the performing stage, consensus and cooperation have been well-established and the team is mature, organized, and well-functioning. There is a clear and stable structure, and members are committed to the team’s mission. Problems and conflicts still emerge, but they are dealt with constructively. The team is focused on problem solving and meeting team goals.

Adjourning stage

In the adjourning stage, most of the team’s goals have been accomplished. The emphasis is on wrapping up final tasks and documenting the effort and results. As the work load is diminished, individual members may be reassigned to other teams, and the team disbands. There may be regret as the team ends, so a ceremonial acknowledgement of the work and success of the team can be helpful. If the team is a standing committee with ongoing responsibility, members may be replaced by new people and the team can go back to a forming or storming stage and repeat the development process.

Positive and Negative Team Roles

When a manager selects a team for a particular project, its success depends on its members filling various positive roles. There are a few standard roles that must be represented to achieve the team’s goals, but diversity is also key. Without an initiator-coordinator stepping up into a leadership position, for instance, the team will be a non-starter because team members such as the elaborator will just wait for more direction from the manager, who is busy with other things. If all the team members commit to filling a leadership role, however, the group will stall from the get-go with power struggles until the most dominant personality vanquishes the others, who will be bitterly unproductive relegated to a subordinate worker-bee role. A good manager must therefore be a good psychologist in building a team with diverse personality types and talents. Table 9.1 below captures some of these roles.

| Role | Actions |

|---|---|

| Initiator-Coordinator | Suggests new ideas or new ways of looking at the problem |

| Elaborator | Builds on ideas and provides examples |

| Coordinator | Brings ideas, information, and suggestions together |

| Evaluator-Critic | Evaluates ideas and provides constructive criticism |

| Recorder | Records ideas, examples, suggestions, and critiques |

| Comic Relief | Uses humor to keep the team happy |

Of course, each team member here contributes work irrespective of their typical roles. The groupmate who always wanted to be recorder in high school because they thought that all they had to do what jot down some notes about what other people said and did, and otherwise contributed nothing, would be a liability as a slacker in a workplace team. We must therefore contrast the above roles with negative roles, some of which are captured in Table 9.2 below.

| Role | Actions |

|---|---|

| Dominator | Dominates discussion so others can’t take their turn |

| Recognition Seeker | Seeks attention by relating discussion to their actions |

| Special-Interest Pleader | Relates discussion to special interests or personal agenda |

| Blocker | Blocks attempts at consensus consistently |

| Slacker | Does little-to-no work, forcing others to pick up the slack |

| Joker or Clown | Seeks attention through humor and distracting members |

Whether a team member has a positive or negative effect often depends on context. Just as the class clown can provide some much-needed comic relief when the timing’s right, they can also impede productivity when they merely distract members during work periods. An initiator-coordinator gets things started and provides direction, but a dominator will put down others’ ideas, belittle their contributions, and ultimately force people to contribute little and withdraw partially or altogether.

Perhaps the worst of all roles is the slacker. If you consider a game of tug-o-war between two teams of even strength, success depends on everyone on the team pulling as hard as they would if they were in a one-on-one match. The tendency of many, however, is to slack off a little, thinking that their contribution won’t be noticed and that everyone else on the team will make up for their lack of effort. The team’s work output will be much less than the sum of its parts, however, if everyone else thinks this, too. Preventing slacker tendencies requires clearly articulating in writing the expectations for everyone’s individual contributions. With such a contract to measure individual performance, each member can be held accountable for their work and take pride in their contribution to solving all the problems that the team overcame on its road to success.

Cultivating a Supportive Group Climate

Any time a group of people comes together, new dynamics are put into place that differ from the dynamics present in our typical dyadic interactions. The impressions we form about other people’s likeability and the way we think about a group’s purpose are affected by the climate within a group that is created by all members.

When something is cohesive it sticks together, and the cohesion within a group helps establish an overall group climate. Group climate refers to the relatively enduring tone and quality of group interaction that is experienced similarly by group members. To better understand cohesion and climate, we can examine two types of cohesion: task and social.

Task cohesion refers to the commitment of group members to the purpose and activities of the group. Social cohesion refers to the attraction and liking among group members. Ideally, groups would have an appropriate balance between these two types of cohesion relative to the group’s purpose, with task-oriented groups having higher task cohesion and relational-oriented groups having higher social cohesion. Even the most task-focused groups need some degree of social cohesion, and vice versa, but the balance will be determined by the purpose of the group and the individual members. For example, a team of workers from the local car dealership may join a local summer softball league because they’re good friends and love the game. They may end up beating the team of faculty members from the community college who joined the league just to get to know each other better and have an excuse to get together and drink beer in the afternoon. In this example, the players from the car dealership exhibit high social and task cohesion, while the faculty exhibit high social but low task cohesion. Cohesion benefits a group in many ways and can be assessed through specific group behaviors and characteristics. Groups with an appropriate level of cohesiveness (Hargie, 2011):

- set goals easily;

- exhibit a high commitment to achieving the purpose of the group;

- are more productive;

- experience fewer attendance issues;

- have group members who are willing to stick with the group during times of difficulty;

- have satisfied group members who identify with, promote, and defend the group;

- have members who are willing to listen to each other and offer support and constructive criticism; and

- experience less anger and tension.

Appropriate levels of group cohesion usually create a positive group climate, since group climate is affected by members’ satisfaction with the group. Climate has also been described as group morale. The following are some qualities that contribute to a positive group climate and morale (Marston & Hecht, 1988):

- Participation. Group members feel better when they feel included in the discussion and a part of the functioning of the group.

- Messages. Confirming messages help build relational dimensions within a group, and clear, organized, and relevant messages help build task dimensions within a group.

- Feedback. Positive, constructive, and relevant feedback contribute to the group climate.

- Equity. Aside from individual participation, group members also like to feel as if participation is managed equally within the group and that appropriate turn-taking is used.

- Clear and accepted roles. Group members like to know how status and hierarchy operate within a group. Knowing the roles isn’t enough to lead to satisfaction, though—members must also be comfortable with and accept those roles.

- Motivation. Member motivation is activated by perceived connection to and relevance of the group’s goals or purpose.

Group cohesion and climate are also demonstrated through symbolic convergence (Bormann, 1985). Have you ever been in a group that had ‘inside jokes’ that someone outside the group just would not understand? Symbolic convergence refers to the sense of community or group consciousness that develops in a group through non-task-related communication such as stories and jokes. The originator of symbolic convergence theory, Ernest Bormann, claims that the sharing of group fantasies creates symbolic convergence. Fantasy, in this sense, doesn’t refer to fairy tales, sexual desire, or untrue things. In group communication, group fantasies are verbalized references to events outside the “here and now” of the group, including references to the group’s past, predictions for the future, or other communication about people or events outside the group (Griffin, 2009).

In any group, you can tell when symbolic convergence is occurring by observing how people share such fantasies and how group members react to them. If group members react positively and agree with or appreciate the teller’s effort or other group members are triggered to tell their own related stories, then convergence is happening and cohesion and climate are being established. Over time, these fantasies build a shared vision of the group and what it means to be a member that creates a shared group consciousness. By reviewing and applying the concepts in this section, you can hopefully identify potential difficulties with group cohesion and work to enhance cohesion when needed to create more positive group climates and enhance your future group interactions.

The Benefits of Team Diversity

Rock and Grant (2016) assert that increasing workplace diversity is a good business decision. Hunt, Layton, and Prince (2015) conducted a study of 366 public companies and found that those in the top quartile for ethnic and racial diversity in management were 35% more likely to have financial returns above their industry mean, and those in the top quartile for gender diversity were 15% more likely to have returns above the industry mean. Similarly, Curtis, Schmid, and Struber (2012) found that organizations with at least one female board member yielded a higher return on equity and higher net income growth than those that did not have any women on the board (Figure 9.10).

Additional research on diversity has shown that diverse teams are better at decision-making and problem-solving because they tend to focus more on facts (Rock & Grant, 2016). Phillips, Liljenquist, and Neale (2008) found that when working together, people from diverse backgrounds can potentially alter the group’s behaviors, leading to more accurate and improved thinking. In their study, the diverse panels raised more facts related to the case than homogeneous panels and made fewer factual errors while discussing available evidence. Additionally, Levine, Apfelbaum, and Bernard (2014) showed that diverse teams are more likely to constantly reexamine facts and remain objective. They may also encourage greater scrutiny of each member’s actions, keeping their joint cognitive resources sharp and vigilant.

By breaking up workforce homogeneity, you can allow your employees to become more aware of their own potential biases—entrenched ways of thinking that can otherwise blind them to key information and even lead them to make errors in decision-making processes. In other words, when people are among homogeneous and like-minded (non-diverse) teammates, the team is susceptible to groupthink and may be reticent to think about opposing viewpoints since all team members are in alignment. In a more diverse team with a variety of backgrounds and experiences, the opposing viewpoints are more likely to come out and the team members feel obligated to research and address the questions that have been raised. Again, this enables a richer discussion and a more in-depth fact-finding and exploration of opposing ideas and viewpoints to solve problems.

Diversity in teams also leads to greater innovation. Lorenzo, Yoigt, Schetelig, Zawadzki, Welpe, & Brosi (2017) sought to understand the relationship between diversity in managers (all management levels) and innovation. The key findings of this study show that:

- The positive relationship between management diversity and innovation is statistically significant—and thus companies with higher levels of diversity derive more revenue from new products and services.

- The innovation boost isn’t limited to a single type of diversity. The presence of managers who are either female or are from other countries, industries, or companies can cause an increase in innovation.

- Management diversity seems to have a particularly positive effect on innovation at complex companies—those that have multiple product lines or that operate in multiple industry segments.

- To reach its potential, gender diversity needs to go beyond tokenism. In the study, innovation performance only increased significantly when the workforce included more than 20% women in management positions. Having a high percentage of female employees doesn’t increase innovation if only a small number of women are managers.

- At companies with diverse management teams, openness to contributions from lower-level workers and an environment in which employees feel free to speak their minds are crucial for fostering innovation.

When you consider the impact that diverse teams have on decision-making and problem-solving—through the discussion and incorporation of new perspectives, ideas, and data—it is no wonder that the BCG study shows greater innovation. Team leaders need to reflect upon these findings during the early stages of team selection so that they can reap the benefits of having diverse voices and backgrounds.

Challenges and Best Practices of Working in Multicultural Teams

As globalization has increased over the last decades, workplaces have felt the impact of working within multicultural teams. The earlier section on team diversity outlined some of the benefits of working on diverse teams, and a multicultural group certainly qualifies as diverse. However, some key practices are recommended to those who are leading multicultural teams to navigate the challenges that these teams may experience.

People may assume that communication is the key factor that can derail multicultural teams, as participants may have different languages and communication styles. However, Brett, Behfar, and Kern (2006) outline four key cultural differences that can cause destructive conflicts in teams. The first difference is direct versus indirect communication, also known as high-context vs low-context orientation. Some cultures are very direct and explicit in their communication, while others are more indirect and ask questions rather than pointing out problems. This difference can cause conflict because, at the extreme, the direct style may be considered offensive by some, while the indirect style may be perceived as unproductive and passive-aggressive in team interactions.

The second difference that multicultural teams may face is trouble with accents and fluency. When team members don’t speak the same language, there may be one language that dominates the group interaction—and those who don’t speak it may feel left out. The speakers of the primary language may feel that those members don’t contribute as much or are less competent. The next challenge is when there are differing attitudes toward hierarchy. Some cultures are very respectful of the hierarchy and will treat team members based on that hierarchy. Other cultures are more egalitarian and don’t observe hierarchical differences to the same degree. This may lead to clashes if some people feel that they are being disrespected and not treated according to their status. The final difference that may challenge multicultural teams is conflicting decision-making norms. Different cultures make decisions differently, and some will apply a great deal of analysis and preparation beforehand. Those cultures that make decisions more quickly (and need just enough information to make a decision) may be frustrated with the slow response and relatively longer thought process.

These cultural differences are good examples of how everyday team activities (decision-making, communication, interaction among team members) may become points of contention for a multicultural team if there isn’t an adequate understanding of everyone’s culture. The authors propose that there are several potential interventions to try if these conflicts arise. One simple intervention is adaptation, which is working with or around differences. This is best used when team members are willing to acknowledge the cultural differences and learn how to work with them. The next intervention technique is structural intervention, or reorganizing to reduce friction on the team. This technique is best used if there are unproductive subgroups or cliques within the team that need to be moved around. Managerial intervention is the technique of making decisions by management and without team involvement. This technique should be used sparingly, as it essentially shows that the team needs guidance and can’t move forward without management getting involved. Finally, exit is an intervention of last resort and is the voluntary or involuntary removal of a team member. If the differences and challenges have proven to be so great that an individual on the team can no longer work with the team productively, then it may be necessary to remove the team member in question.

Conflict Within Teams

Conflict occurs wherever people interact, both at home and at work. If employees don’t get along with one another or their employers, there’s very little motivation to do good work. Learning how to identify and navigate conflict is an important life skill that will prove to be extremely helpful, especially in the workplace. Professionally managing conflict will help to foster healthy working environments and create strong working relationships amongst coworkers and managers alike.

Any time individuals interact, there is potential for conflict. Conflict occurs when differing interests and ideas collide, creating tension. Conflict is a natural part of everyday life, especially in the workplace. With compensation, deadlines, clients, etc. on the line, it is normal for the workplace to add additional stress and pressure to the challenges of everyday life. Therefore, it is more likely people will encounter conflict at work.

Common Types of Team Conflict

Conflict is a common occurrence on teams. Conflict itself can be defined as antagonistic interactions in which one party tries to block the actions or decisions of another party. Bringing conflicts out into the open where they can be resolved is an important part of the team leader’s or manager’s job.

There are two basic types of team conflict: substantive (sometimes called task) and emotional (or relationship).

- Substantive conflicts arise over things such as goals, tasks, and the allocation of resources. When deciding how to track a project, for example, a software engineer may want to use a certain software program for its user interface and customization capabilities. The project manager may want to use a different program because it produces more detailed reports. Conflict will arise if neither party is willing to give way or compromise on his position.

- Emotional conflicts arise from things such as jealousy, insecurity, annoyance, envy, or personality conflicts. It is emotional conflict when two people always seem to find themselves holding opposing viewpoints and have a hard time hiding their personal animosity. Different working styles are also a common cause of emotional conflicts. Julia needs peace and quiet to concentrate, but her office mate swears that playing music stimulates his creativity. Both end up being frustrated if they can’t reach a workable resolution.

Common Causes of Conflict

Some common causes of negative conflict in teams are identified as follows:

- Conflict often arises when team members focus on personal (emotional) issues rather than work (substantive) issues. Enrico is attending night school to get his degree, but he comes to work late and spends time doing research instead of focusing on the job. The other team members have to pick up his slack. They can confront Enrico and demand his full participation, they can ignore him while tensions continue to grow, or they can complain to the manager. All the options will lower team performance.

- Competition over resources, such as information, money, supplies or access to technology, can also cause conflict. Maria is supposed to have use of the laboratory in the afternoons, but Jason regularly overstays his allotted time, and Maria’s work suffers. Maria might try to “get even” by denying Jason something he needs, such as information, or by complaining to other team members.

- Communication breakdowns cause conflict—and misunderstandings are exacerbated in virtual teams and teams with cross-cultural members. The project manager should be precise in his expectations from all team members and be easily accessible. When members work independently, it is critical that they understand how their contributions affect the big picture in order to stay motivated. Carl couldn’t understand why Latisha was angry with him when he was late with his reports—he didn’t report to her. He didn’t realize that she needed his data to complete her assignments. She eventually quit, and the team lost a good worker.

Team morale can be low because of external work conditions such as rumors of downsizing or fears that the competition is beating them to market. A manager needs to understand what external conditions are influencing team performance.

Summary

- Teams go through five definitive stages during development: forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning.

- The success of work teams relies on individuals filling different positive roles, however work teams can fail if too many individuals take on negative roles.

- Group climate refers to the relatively enduring tone and quality of group interaction that is experienced similarly by group members

- The benefits of team diversity include better decision-making and problem-solving and opposing viewpoints are more likely to come out.

- There are two basic types of team conflict: substantive (sometimes called task) and emotional (or relationship).

Discussion Questions

- Recall a previous or current small group to which you belonged/belong. Trace the group’s development using the five stages discussed in this section. Did you experience all the stages? In what order? Did you stay in some stages more than others?

- Discuss a team you were a part of that included a member who took on one of the positive team roles or one of the negative team roles in the team. What actions did they engage in? How did their actions impact the team’s ability to work?

- Describe a substantive conflict and an emotional conflict you’ve experienced or witness at your place of work. How were these conflicts resolved?

Remix/Revisions featured in this section

- Small editing revisions to tailor the content to the Psychology of Human Relations course.

- Remix of combining The Five Stages of Team Development and Conflict Within Teams (Principles of Management – Lumen Learning) with 5.2 Small Group Dynamics and 5.4 Working in Diverse Teams(Conflict Management – Open Library)

- Added images and provided links to locations of images and CC licenses.

- Added doi links to references to comply with APA 7th edition formatting reference manual.

Attributions

CC Licensed Content, Original

Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Stevy Scarbrough. License: CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Conflict Management Authored by: Laura Westmaas. Published by: Open Library Located at: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/conflictmanagement/ License: CC BY 4.0

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Principles of Management Authored by: John Bruton, Lynn Bruton. Published by: Lumen Learning Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-principlesmanagement/ License: CC BY 4.0

References

Bormann, E. G. (1985). Symbolic convergence theory: A communication formulation. Journal of Communication, 35(4), 128–38.

Brett, J., Behfar, K., Kern, M. (2006, November). Managing multicultural teams. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2006/11/managing-multicultural-teams

Curtis, M., Schmid, C., & Struber, M. (2012). Gender diversity and corporate performance. Credit Suisse Research Institute. https://women.govt.nz/sites/public_files/Credit%20Suisse_gender_diversity_and_corporate_performance_0.pdf

Griffin, E. (2009). A first look at communication theory (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal interaction: Research, theory, and practice (5th ed.). Routledge.

Hunt, V., Layton, D., & Prince, S. (2015, January 1). Why diversity matters. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved November 19, 2022 from https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/why-diversity-matters

Levine, S. S., Apfelbaum, E. P., & Bernard, M. (2014). Ethnic diversity deflates price bubbles. Proceedings of the National academy of Sciences, 111(52) 18524-18529. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1407301111

Lorenzo, R., Yoigt, N., Schetelig, K., Zawadzki, A., Welpe, I., & Brosi, P. (2017, April 26). The mix that matters: Innovation through diversity. Retrieved November 19, 2022 from https://www.bcg.com/publications/2017/people-organization-leadership-talent-innovation-through-diversity-mix-that-matters

Marston, P. J., & Hecht, M. L. (1988). Group satisfaction. In R. Cathcart & L. Samovar (Eds.), Small group communication (5th ed.). Brown.

Phillips, K. W., Liljenquist, K. A., & Neale, M. A. (2008). Is the pain worth the gain? The advantages and liabilities of agreeing with socially distinct newcomers. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(3), 336-350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208328062

Rock, D., & Grant, H. (2016, November 4). Why diverse teams are smarter. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter

Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022100