2.3 Diversity in the Workplace

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Differentiate between social diversity and social progress

- Discuss the benefits and challenges of a diverse workforce

We all have our strengths and our weaknesses, things we excel in and things we struggle with. We have our endearing personality traits and our sometimes-annoying ones. Could you imagine working only with people exactly like you, from the same background, with the same experiences, the same personalities? Probably not. And that’s a good thing. Diversity helps to keep things interesting, exciting, and progressing. Interacting with a large variety of individuals can help stimulate your mind and present ideas and opinions you may not have ever discovered on your own.

Recognizing diversity in your daily life can help you to see the world from new and different perspectives. Diversity is an essential part of every organization and it is important to recognize how it influences the workforce (Figure 2.6). Understanding diversity can help us to work better in group or team situations and gives us insight into the behavior of an organization. This section will explore the history, complexity, benefits, and challenges of diversity in the workplace.

Social Diversity and Social Progress

Let’s start with the basics. What is diversity? Grab a pen and a piece of paper. Quickly jot down how you would define diversity. What’s the first thing that came to mind? Take a minute to write your response and then continue reading.

When students from UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health were asked to define diversity, they each recorded their response. You can check out their responses. Take a minute to compare your answers to theirs. Chances are, there were similar themes between your answers and theirs, but your response did not identically match any of the others. This is the perfect way to define diversity.

Each of us are different. Everyone comes with different backgrounds and experiences. Diversity cannot be simply defined by a variety of ethnicities or races. It can also not be simply described as people from different countries or cultures. Instead, diversity encompasses all of these things and more. Diversity includes but is not limited to language, religion, marital status, gender, age, socioeconomic status, geography, politics—and the list goes on and on.

Now that we have reviewed diversity, we need to discuss social diversity. You’re probably wondering how the two are different. Santana (2018) defines social diversity as a successful community which includes individuals from diverse backgrounds who all contribute to the success of the community by practicing understanding and respect of different ideas and perspectives. Santana explains that successful socially diverse communities are able to work together to achieve common goals.

While the two terms have a lot of similarities, diversity is defined by a variety of differences between individuals whereas social diversity describes how a community, society, or organization utilizes their members’ diversity to work towards a common goal. Lastly, we need to define and discuss social progress.

Harvard Business School’s Social Progress Index defines social progress as, “the capacity of a society to meet the basic human needs of its citizens, establish the building blocks that allow citizens and communities to enhance and sustain the quality of their lives, and create the conditions for all individuals to reach their full potential.” Let’s break it down to better understand the many aspects of social progress.

There are many lenses in which to view social progress. For the purpose of this section, we will specifically focus on social progress in the workplace. Let’s focus on the last part of the definition, “to enhance and sustain the quality of their lives, and create the conditions for all individuals to reach their full potential.” Simply put, social progress is the idea of giving people from all backgrounds the opportunity and environment to work towards their goals and success. Now, how is social progress different from social diversity? Social progress should be constantly evolving and changing to ensure people can reach their full potential whereas social diversity is a term that evaluates where a community or organization is currently operating.

History of Social Progress

To completely understand social progress on a global scale, you would have to dedicate your life to studying the ins and outs of cultures and societies around the globe. Since we do not have a lifetime to discuss social progress for the purpose of this course, we will review the history of social progress in America over the last century. Even more specifically, we will discuss the history of social progress in America’s workplaces. It is important to examine the history of social progress in order to fully comprehend how times have changed in the past century and also to better recognize opportunities in which we need to evolve and improve.

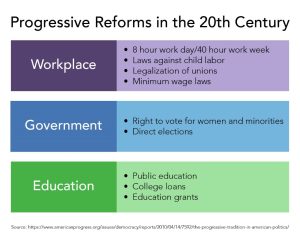

The Progressive Era began in the late 1800s and focused on both political and ethical reform. Progressives argued that business organizations needed to be more regulated in order to ensure economic opportunity for all. Progressives believed that all people deserved the opportunity to flourish through government regulations controlling workplace environments, hiring practices, unions, child labor, minimum wage, etc. While many of these things will appear to be common sense by today’s standards, these were controversial and rebellious ideas in the early 1900s (Figure 2.7).

The Progressive Era created a domino effect of social change. While change has been slow at times, a lot has happened since the start of the 20th century. In 1948 President Truman signed what is believed by many to be the first workplace diversity initiative on record. Executive Order 9981 ordered a desegregation of the armed services. Although it did not prohibit segregation, it did mandate equal treatment and opportunity for all people in the armed services, regardless of their race or ethnicity.

Then, in the 1960s, The Civil Rights Act was passed, prohibiting discrimination based on race, religion, national origin, or sex. This was a huge step in the history of social progress as it drastically changed the number of opportunities available to people from all backgrounds. Next, in 1987, Workforce 2000 was created, discussing factors that would have an impact on the US workforce in the decades to come.

Workforce 2000 was created in the late 1980s and discussed a variety of factors predicted to influence America’s workforce by the year 2000. The Workforce 2000 document was authored by the Hudson Institute, an Indianapolis, Indiana company, and sponsored by the United States Department of Labor. Hudson Institute’s mission statement is, “to think about the future in unconventional ways” and that is exactly what they did.

Hudson Institute identified four trends they believed would prove to be true by the year 2000. They are as follows:

- The American economy should grow at a relatively healthy pace

- Manufacturing will be a much smaller share of the economy in the year 2000

- The workforce will grow slowly, becoming older, more female, and more disadvantaged

- The new jobs in service industries will demand much higher skill levels than jobs of today

While all four of these expected trends are interesting on a variety of levels, for the purpose of this class, let’s focus on number three and how it helped to identify diversity changes in the workplace.

The report stated that the number of women and minorities entering into the workforce would grow by the year 2000. Some people believed the report suggested the total number of employees per organization would be comprised of more women and minorities than straight white cisgender men. However, the report clearly stated that the overall additions to the workforce would be comprised of more women and minorities rather than the total. Therefore, while they predicted an increase in the number of women and minorities, they did not predict a large overall percentage change in the makeup of organizations. Although the overall change to the workforce would appear to be minor, the trends presented in the report began to change society’s way of thinking. Workforce diversity became a topic of conversation both in and out of the workforce, helping to develop the birth of the diversity industry.

Many companies acknowledged a change in workforce demographics were on the horizon; however, very few companies recognized how diversity could positively influence a company’s bottom-line. Instead of welcoming the diverse backgrounds and experiences of their newly acquired female and minority employees, they focused on getting them to adapt to the current company majority. In many cases, a company’s diversity was only reflected through the way their employees looked, not in the way their employees behaved and operated. Training and development was focused on getting the new employees to adapt to the current way of doing things, instead of training the whole company to view business operations from a variety of new perspectives. While assimilation is important to foster fluidity within an organization, utilizing the diverse backgrounds and experiences of employees can help propel operations and output to the next level. Being able to properly manage diversity, in all aspects of the term, became a new focus for many organizations and opened the door for a new era of diversity training and appreciation.

Since there was a new focus on diversity, specifically for hiring and including women and minorities, some current members of the workforce began to feel ostracized. White males specifically were viewed as a diversity problem, and their issues and concerns were not validated because they were the majority, not the minority. This forced people to revisit the concept of diversity, reminding people that diversity includes all people from all backgrounds and that includes white males. All these new concepts and ideas created discussions that are still being held today. For example, there is still a debate about the importance of including white males in the realm of diversity or solely focusing on the traditionally underrepresented groups. Also, does diversity primarily include ethnicity, sexuality, religion, and age? Or does it also include education, socioeconomic background, and previous experiences? Society and the business world are still working their way through some of these conversations today.

Diversity and social progress continue to be an important focus for companies and the way companies foster diversity continues to develop and grow. In today’s workplace, companies can promote diversity through domestic partner benefits, paid maternity/paternity leave, flexible schedules, a range of dress code requirements, etc. At the end of this module, we will discuss strategies and ideas you can use to encourage and promote diversity in the workplace.

While this was just a quick review into the history of social progress, hopefully it gave some insight into how much American organizations have grown and developed over the last century. While there are still changes on the horizon, modern society is more open to diversity and what it can bring to the table.

Complexity of Diversity in the Workplace

As we have discussed, diversity is everywhere, including the workplace. Diversity can be defined on a variety of levels. There are both external and internal factors that need to be considered when discussing diversity. External diversity is often displayed in a person’s appearance. External diversity can include but is not limited to, gender, age, ethnicity, and sometimes even religion. It is also important to note that even external diversity traits are not always easy to identify as not everyone ages the same or looks the same, even if they’re from the same part of the world or expressed their gender in the same way.

Internal diversity, on the other hand, is even more challenging to define and identify. Internal diversity includes individual experiences and backgrounds. Internal diversity examples may include how people were raised, where they went to school, previous job experience, etc.

Not every piece of the diversity puzzle can fit neatly into a category. Diversity is extremely complex and incorporates almost every aspect of a person’s life. You may find people that are similar to you and have similar core values and beliefs; however, there is no one who is exactly like you because everyone has different experiences throughout their lifetime. Even similar interactions and experiences may have a different effect on each individual who lives it.

The workplace is equally as complex as the rest of society. Once again, the workplace will not identically mirror society but it still experiences similar diversity challenges. We will now examine the benefits and challenges of having a diverse workplace.

Benefits of Diversity in the Workplace

UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center’s (GGSC) definition of diversity captures not only that essential element of difference but why it matters. To quote: “‘diversity’ refers to both an obvious fact of human life—namely, that there are many different kinds of people—and the idea that this diversity drives cultural, economic, and social vitality and innovation.’” From a human resource management standpoint, it’s important to note that diversity benefits both the organization and individuals. GGSC cites research indicating that “individuals thrive when they are able to tolerate and embrace the diversity of the world.” Of course, the opposite is also true: intolerance undermines our well-being.

Hunt, Prince, Dixon-Fyle, and Yee (2018) observe that “While social justice, legal compliance, or maintaining industry-standard employee environment protocols is typically the initial impetus behind these efforts, many successful companies regard I&D [inclusion & diversity] as a source of competitive advantage, and specifically as a key enabler of growth.” The authors found that the business case for diversity and inclusion remains compelling, listing the following benefits:

- Diversity drives business performance. A more diverse leadership team correlates with financial outperformance.

- Executive diversity (gender++) matters. The companies with the highest gender diversity on their executive teams tend to have higher profitability. Additionally, ethnic and cultural diversity of executive also leads to higher profitability.

- Lack of diversity impairs business results. Companies that opt out of building a diverse workforce are less likely to be as profitable as companies that work toward a diverse workforce.

Hunt et al. (2018) found that companies with more diversity are better able to attract top talent and increase employee satisfaction, leading to a positive relationship between inclusion and diversity and performance. The following benefits outlined by Reynolds (2019) expand upon these findings:

- Greater creativity and innovation—diversity of thought—for example, different experiences, perspectives and cognitive styles—can stimulate creativity and drive innovation.

- Improved competitive positioning—“local knowledge”—everything from local laws and customs to connections, language and cultural fluency—can increase the probability of success when entering a new country or region.

- Improved marketing effectiveness—having an understanding of the nuances of culture and language is a prerequisite for developing appropriate products and marketing materials. The list of gaffes is endless…and the financial and brand impact of errors can be significant, from a line of Nike Air shoes that were perceived to be disrespectful of Allah to the poor Chinese translation of KFC’s “Finger lickin’ good tagline: “so tasty, you’ll eat your fingers off!”

- Improved talent acquisition & retention—this is particularly critical in a competitive job market: embracing diversity not only increases the talent pool, it improves candidate attraction and retention. A Glassdoor survey found that 67% of job seekers indicated that diversity was an important factor when evaluating companies and job offers. Reynolds also cites HR.com research that indicates diversity, including diversity of gender, religion, and ethnicity, improves retention.

- Increased organizational adaptability—hiring individuals with a broader base of skills and experience and cognitive styles will likely be more effective in developing new products and services, supporting a diverse client base and will allow an organization to anticipate and leverage market and socio-cultural or political developments/opportunities.

- Greater productivity—research has shown that the range of experience, expertise and cognitive styles that are implicit in a diverse workforce improve complex problem-solving, innovation and productivity.

- Greater personal and professional growth—learning to work across and leverage differences can be an enriching experience and an opportunity to build a diverse network and develop a range of high-value soft skills including communication, empathy, collaborative problem-solving and multicultural awareness. To that point, GGSC reports that a study published in Psychological Science found that “social and emotional intelligence rises as we interact with more kinds of people.”

Challenges of Diversity in the Workplace

What makes us different can also make it challenging for us to work well together. Challenges to employee diversity are based not only on our differences—actual or perceived—but on what we perceive as a threat. Our micro (e.g., organizational culture) and macro (e.g., socio-political and legal) operating environment can also be challenges for diversity. Long-term economic, social, political and environmental trends are rendering entire industries—and the associated skill sets—obsolete. For many in these industries and many slow-growth occupations, workplace trends seem to represent a clear and present danger.

Buckley and Bachman (2017) state that the U.S. labor market is increasingly dividing into two categories: “highly skilled, well-paid professional jobs and poorly paid, low-skilled jobs.” There are relatively fewer middle-skill, moderate-pay jobs—for example, traditional blue-collar or administrative jobs. The idea of a static set of skills for a given occupation is a historical concept. Participation in the future labor force will increasingly require computer and mathematical skills, even at the low-skill end.

Buckley and Bachman (2017) also predict that the workforce of the future will be older (“70 is the new 50”), more diverse and more highly educated stating that “if current trends continue, tomorrow’s workforce will be even more diverse than today’s—by gender, by ethnicity, by culture, by religion, by sexual preference and identification, and perhaps by other characteristics we don’t even know about right now.”

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (2015) projects that by 2024, less than 60% of the labor force will identify as “white non-Hispanic,” down from over 75% in 1994. Hispanic individuals are projected to comprise approximately 20% of the 2024 labor force, African-Americans 13% and Asians 7%. Women are expected to comprise 47% of the 2024 workforce. For many, these economic and demographic shifts represent a radical change. Macro level challenges to diversity include fixed mindsets, economic trends and outdated socio-political frameworks. Reynolds (2019) lists specific challenges to diversity that may be experienced at the organizational level:

- Complexity. This is the flip-side of one of diversity’s benefits: it’s hard work! Reynolds notes that while it might seem easier to work on a homogeneous team, there is a tendency to compromise and “settle for the status quo.” Rock, Grant, and Grey (2016) argue that “working on diverse teams produces better outcomes precisely because it’s harder.”

- Differences in communication behaviors. Different cultures have different communication rules or expectations. For example, colleagues from Asian or Native American cultures may be less inclined to “jump in” or offer their opinions due to politeness or deference as a new member or the only [fill in the blank] on the team.

- Prejudice or negative stereotypes. Prejudice, negative assumptions or perceived limitations can negate the benefits of diversity and create a toxic culture. The oversimplifications of stereotypes can be divisive and limiting in the workplace. Additionally, unconscious biases are often more challenging to maintaining workplace diversity.

- Differences in language and non-verbal communications. George Bernard Shaw quipped “The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” Clearly, language differences can be a challenge, including accents and idioms. Translation errors can also occur with non-verbal communication; gestures, eye contact, personal space and greeting customs can be significantly (and disastrously) different across cultures and regions.

- Complexity & cost of accommodations. Hiring a non-U.S. citizen may require navigating visas and employment law as well as making accommodations for religious practices and non-standard holidays.

- Differences in professional etiquette. Differences in attitudes, behaviors and values ranging from punctuality to the length of the work day, form of address or how to manage conflict can cause tensions.

- Conflicting working styles across teams. In addition to individual differences, different approaches to work and team work—for example, the relative value of independent versus collaborative/collective thought and work—can derail progress.

Diversity and the Law

Thus far we have examined the history of social diversity, and addressed the benefits and challenges of having a diverse workforce. The progress that has been made in developing more diverse workplaces has been aided by various laws and policies, some of which were mentioned in discussing the history of social progress. We will now look more closely at the current laws impacting diversity in the workplace.

Employment Legislation

What happens when businesses make decisions that violate laws and regulations designed to protect working Americans? As a Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) training manual emphasizes: “Discrimination cost employers millions of dollars every year, not to mention the countless hours of lost work time, employee stress and the negative public image that goes along with a discrimination lawsuit.”

Equal employment opportunity isn’t just the right thing to do, it’s the law. Specifically, it’s a series of federal laws and amendments designed to eliminate employment discrimination. Employment discrimination laws and regulations are enforced by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), an agency established by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII). The agency’s mission is to stop and remedy unlawful employment discrimination. Specifically, the EEOC is charged with “enforcing federal laws that make it illegal to discriminate against a job applicant or an employee because of the person’s race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy, gender identity, and sexual orientation), national origin, age (40 or older), disability or genetic information” (Figure 2.8) (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission). Since its creation in 1964, Congress has gradually expanded EEOC powers to include the authority to investigate claims, negotiate settlements and file lawsuits. The agency also conducts outreach and educational programs in an effort to prevent discrimination. Finally, the EEOC provides equal employment opportunity advisory services and technical support to federal agencies.

Anti-Discrimination Legislation

The intent of U.S. anti-discrimination legislation is to protect workers from unfair treatment. In brief, illegal discrimination is the practice of making employment decisions based on factors unrelated to performance.

In 1964, the United States Congress passed the first Civil Rights Act. In 1963 when the legislation was introduced, the act only forbade discrimination on the basis of sex and race in hiring, promoting, and firing. However, by the time the legislation was finally passed on July 2, 1964, Section 703 (a) made it unlawful for an employer to “fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions or privileges or employment, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

Over the years, amendments to the original act have expanded the scope of the law, and today the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission enforces laws that prohibit discrimination based on seven protected categories including age, disability, genetic information, national origin, pregnancy, race, color, religion, and sex. Federal anti-discrimination laws apply to a broad range of employee actions. Specifically, any employment decision – including hiring, compensation, scheduling, performance evaluation, promotion, firing or any other term or condition of employment – that is based on factors unrelated to performance is illegal.

While the Civil Rights Act of 1964 did not mention the words affirmative action, it did authorize the bureaucracy to makes rules to help end discrimination. Affirmative action refers to both mandatory and voluntary programs intended to affirm the civil rights of designated classes of individuals by taking positive action to protect them from discrimination. The first federal policy of race-conscious affirmative action emerged in 1967 and required government contractors to set “goals and timetables” for integrating and diversifying their workforce. Similar policies began to emerge through a mix of voluntary practices and federal and state policies in employment and education. These include government-mandated, government-sanctioned, and voluntary private programs that tend to focus on access to education and employment, specifically granting special consideration to historically excluded groups such as racial minorities or women. The impetus toward affirmative action is redressing the disadvantages associated with past and present discrimination. A further impetus is the desire to ensure that public institutions, such as universities, hospitals, and police forces, are more representative of the populations they serve.

In the United States, affirmative action tends to emphasize not specific quotas but rather “targeted goals” to address past discrimination in a particular institution or in broader society through “good-faith efforts . . . to identify, select, and train potentially qualified minorities and women.” For example, many higher education institutions have voluntarily adopted policies that seek to increase recruitment of racial minorities. Another example is executive orders requiring some government contractors and subcontractors to adopt equal opportunity employment measures, such as outreach campaigns, targeted recruitment, employee and management development, and employee support programs.

As discussed above, the EEOC is the organization charged with implementing Title VII and related anti-discrimination legislation. There are currently seven categories protected under federal law: age, disability, genetic information, national origin, race and color, religion and sex. The EEOC’s authority includes enforcing the following federal statutes summarized below. Unless otherwise stated, these laws apply to most employers with at least 15 employees (20 employees for the ADEA), including employment agencies and labor unions.

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964: Prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. The law also makes it illegal to retaliate against a person who has voiced a grievance, filed a charge of discrimination or participated in an investigation or lawsuit. The prohibition against sexual harassment falls under Title VII of this act. As defined by the EEOC, “It is unlawful to harass a person (an applicant or employee) because of that person’s sex.” Harassment can include “sexual harassment” or unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature.

- An amendment to Title VII, The Pregnancy Discrimination Act prohibits discrimination against a woman based on pregnancy, childbirth or a related condition. As in the original law, it also makes retaliation illegal.

- The Equal Pay Act of 1963 (EPA): Prohibits discrimination on the basis of gender in compensation for substantially similar work under similar conditions. In essence, men and women doing equal jobs must receive the same pay. Since the EPA’s enactment, there has been significant – if slow – progress in achieving pay equity. Although progress has often stalled or reversed, the wage gap has narrowed consistently in recent years. Since 1963, the wage gap has decreased from 58.9% to 80.5% in 2017. For perspective: at this percentage, a woman would need to work through April 10 of the next year to make what a man in an equivalent role earned the prior year.

- The Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 (ADEA): Prohibits employment discrimination against individuals 40 years of age or older based on age. As with other anti-discrimination legislation, the law makes retaliation illegal.

- Title I of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA): Prohibits discrimination against a qualified person with a disability and requires employers to make reasonable accommodations for applicants and employees with known physical or mental limitations who are otherwise qualified unless that accommodation would pose an “undue hardship” or material impact (significant difficulty or expense) on an employer’s business operations. As with other anti-discrimination legislation, the law makes retaliation illegal. This law applies to private sector and state and local government employers only. Disability discrimination protection at the federal level is provided in Sections 501 and 505 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. There are three kinds of reasonable accommodations defined by the EEOC (29 CFR § 1630.2 – Definitions):

-

-

- “modifications or adjustments to a job application process that enable a qualified applicant with a disability to be considered for the position such qualified applicant desires; or

- modifications or adjustments to the work environment, or to the manner or circumstances under which the position held or desired is customarily performed, that enable a qualified individual with a disability to perform the essential functions of that position; or

- modifications or adjustments that enable a covered entity’s employee with a disability to enjoy equal benefits and privileges of employment as are enjoyed by its other similarly situated employees without disabilities.”

-

- The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA): Prohibits discrimination against applicants or employees based on an individual’s or his or her family’s genetic information or family medical history (for example, a hereditary disease, disorder or medical condition). As with other anti-discrimination legislation, the law makes retaliation illegal.

Despite the public relations and financial risk of discriminatory hiring practices, charges of workplace discrimination are in the tens of thousands annually. Since 1997, the number of charges has ranged from a low of 75,428 in 2005 to a high of 99,947 in 2011. In fiscal year 2017, the EEOC received 84,254 charges of workplace discrimination charges and obtained $398 million in monetary benefits for victims through a combination of voluntary resolutions and litigation. As was true for the last few years, retaliation was the most frequently filed charge (49%), followed by race (34%), disability (32%), sex (30%) and age (22%). Percentages for the remaining categories range from less than 1% to 10%.

Although retaliation charges are up 3 percentage points from the prior year, 2016 percentages in the remaining top five categories were within a percentage point, with race at 35%, disability at 31%, sex at 29% and age at 23%. Note that percentages add up to more than 100 due to charges alleging multiple bases of discrimination.

Note that state and local laws may provide broader discrimination protections. If in doubt, contact your state department of labor for clarification. Note as well that laws are subject to interpretation. For example, an EEOC notice emphasizes that their interpretation of the Title VII reference to “sex” is broadly applicable to gender, gender identity and sexual orientation. And, further, that “these protections apply regardless of any contrary state or local laws.”

In the Press Release announcing the 2017 data, EEOC Acting Chair Victoria A Lipnic stated that results for the fiscal year demonstrate that “the EEOC has remained steadfast in its commitment to its core values and mission: to vigorously enforce our nation’s civil rights laws.”

EEO Best Practices

As part of its E-Race (Eradicating Racism & Colorism from Employment) Initiative, the EEOC has identified a number of best practices that are applicable broadly, including the following:

Training, Enforcement, and Accountability

Ensure that management—specifically HR managers—and all employees know EEO laws. Implement a strong EEO policy with executive level support. Hold leaders accountable. Also: If using an outside agency for recruitment, make sure agency employees know and adhere to relevant laws; both an agency and hiring organization is liable for violations.

Promote an Inclusive Culture

It’s not just enough to talk about diversity and inclusion—it takes work to foster a professional environment with respect for individual differences. Make sure that differences are welcomed. Being the “only” of anything can get tiring, so make sure you’re not putting further pressure on people by surrounding them in a culture that encourages conformity. A great way to promote an inclusive culture is to make sure your leadership is diverse and to listen to the voices of minorities.

Develop Communication

Fostering open communication and developing an alternative dispute-resolution (ADR) program may reduce the chance that a miscommunication escalates into a legally actionable EEO claim. If you’re not providing a path for employees to have issues resolved, they’ll look elsewhere. Additionally, it’s essential to protect employees from retaliation. If people think reporting an issue will only make the situation worse, they won’t bring it up, which will cause the issue to fester and lead to something worse than it once was.

Evaluate Practices

Monitor compensation and evaluation practices for patterns of potential discrimination and ensure that performance appraisals are based on job performance and accurate across evaluators and roles.

Audit Selection Criteria

Ensure that selection criteria do not disproportionately exclude protected groups unless the criteria are valid predictors of successful job performance and meet the employer’s business needs. Additionally, make sure that employment decisions are based on objective criteria rather than stereotypes or unconscious bias.

Make HR Decisions with EEO in Mind

Implement practices that diversify the candidate pool and leadership pipeline. Provide training and mentoring to help employees thrive. All employees should have equal access to workplace networks.

Enforce an Anti-Harassment Policy

Establish, communicate and enforce a strong anti-harassment policy. You should conduct periodic training for all employees and enforce the policy. The policy should include:

- A clear explanation of prohibited conduct, including examples

- Clear assurance that employees who make complaints or provide information related to complaints will be protected against retaliation

- A clearly described complaint process that provides multiple, accessible avenues of complaint

- Assurance that the employer will protect the confidentiality of harassment complaints to the extent possible

- A complaint process that provides a prompt, thorough, and impartial investigation

- Assurance that the employer will take immediate and appropriate corrective action when it determines that harassment has occurred

EEO Complaints

If an employee believes they were or are being discriminated against at work based on a protected category, the person can file a complaint with the EEOC or a state or local agency (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission). For example, in California, a discrimination claim can be filed either with the state’s administrative agency, the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing (DFEH) or the EEOC. Workplacefairness.org notes that the “California anti-discrimination statute covers some smaller employers not covered by federal law. Therefore, if your workplace has between 5 and 14 employees (or one or more employees for harassment claims), you should file with the DFEH” (Workplace Fairness). California law also addresses language discrimination—for example, “English-only” policies. In brief, “an employer cannot limit or prohibit employees from using any language in the workplace unless there is a business necessity for the restriction.” This section discusses private-sector EEO complaints and enforcement. Federal job applicants and employees follow a different process, linked here: federal EEO complaint process.

Who Should File

If federal EEO law applies your workplace and you believe you were discriminated against at work because of your race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy, gender identity, and sexual orientation), national origin, age (40 or older), disability or genetic information, you can file a charge of discrimination with the EEOC.

Filing a charge of discrimination involves submitting a signed statement asserting that an employer, union or labor organization engaged in employment discrimination. The claim serves as a request for the EEOC to take remedial action. Note that an individual, organization, or agency is allowed to file a charge on behalf of another person in order to protect that person’s identity. A person (or authorized representative) is required to file a Charge of Discrimination with the EEOC prior to filing a job discrimination lawsuit based on EEO laws with the exception of the Equal Pay Act. Under the Equal Pay Act, you are allowed to file a lawsuit and go directly to court.

How to File

To start the process, you can use the EEOC’s Public Portal to submit an inquiry or schedule an “intake” interview. The Public Portal landing page also has a FAQ section and Knowledge Base and allows you to find a local office and track your case. The two most frequently accessed articles are linked below:

- What happens during an EEOC intake interview?

- If I submit an online inquiry, does that mean I filed a charge of discrimination?

The second step in the process is to participate in the interview process. The interview allows you to discuss your employment discrimination situation with an EEOC staff member and determine whether filing a charge of discrimination is the appropriate next step for you. The decision of whether to file or not is yours.

The third step in the process, filing a Charge of Discrimination, can be completed through the Public Portal site.

When to File

The general rule is that a charge needs to be filed within 180 calendar days from the day the discrimination took place. Note that this time frame includes weekends and holidays, except for the final day. This time frame is extended to 300 calendar days if a state or local agency enforces a law that prohibits employment discrimination on the same basis. However, in cases of age discrimination, the filing deadline is only extended to 300 days if there is a state law prohibiting age discrimination in employment and a state agency authorized to enforce that law.

If more than one discriminatory event took place, the deadline usually applies to each event. The one exception to this rule is when the charge is ongoing harassment. In that case, the deadline to file is within 180 or 300 days of the last incident. In conducting its investigation, the agency will consider all incidents of harassment, including those that occurred more than 180/300 days earlier.

If you are alleging a violation of the Equal Pay Act, the deadline for filing a charge or lawsuit under the EPA is two years from the day you received the last discriminatory paycheck. This timeframe is extended to three years in the case of willful discrimination. Note that if you have an Equal Pay Act claim, you may want to pursue remedy under both Title VII and the Equal Pay Act. The EEOC recommends talking to a field staff to discuss your options.

Key point: filing deadlines will generally not be extended to accommodate an alternative dispute resolution process—for example, following an internal or union grievance procedure, arbitration or mediation. These resolution processes may be pursued concurrently with an EEOC complaint filing. The EEOC is required to notify the employer that a charge has been filed against it.

If you have 60 days or less to file a timely charge, refer to the EEOC Public Portal for special instructions or contact the EEOC office closest to you.

Claim Assessment

The EEOC is required to accept all claims related to discrimination. If the EEOC finds that the laws it enforces are not applicable to a claim, that a claim was not filed in a timely manner or that it is unlikely to be able to establish that a violation occurred, the agency will close the investigation and notify the claimant.

Claim Notice

Within 10 days of a charge being filed, the EEOC will send the employer a notice of the charge.

Mediation

In some cases, the agency will ask both the claimant and employer to participate in mediation. In brief, the process involves a neutral mediator who assists the parties in resolving their employment disputes and reaching a voluntary, negotiated agreement. One of the upsides of mediation is that cases are generally resolved in less than three months—less than a third of the time it takes to reach a decision through investigation. For more perspective on mediation, visit the EEOC’s Mediation web page.

Investigation

If the charge is not sent to mediation, or if mediation doesn’t resolve the charge, the EEOC will generally ask the employer to provide a written response to the charge, referred to as the “Respondent’s Position Statement.” The EEOC may also ask the employer to answer questions about the claims in the charge. The claimant will be able to log in to the Public Portal and view the position statement. The claimant has 20 days to respond to the employer’s position statement.

How the investigation proceeds depends on the facts of the case and information required. For example, the EEOC may conduct interviews and gather documents at the employer site or interview witnesses and request documentation. If additional instances of discriminatory behavior take place during the investigation process, the charge can be “amended” to include those charges or an EEOC agent may recommend filing a new charge of discrimination. If new events are added to the original charge or a new charge is filed, the new or amended charge will be sent to the employer and the new events will be investigated along with the prior events.

EEOC Decision

Once the investigation has been completed—on average, a ten-month process—the claimant and employer are notified of the result. If the EEOC determines the law may have been violated, the agency will attempt to reach a voluntary settlement with the employer. Barring that, the case will be referred to EEOC’s legal staff (or, in some cases, the Department of Justice), to determine whether the agency should file a lawsuit.

Right to Sue

If the EEOC decides not to file suit, the agency will give the claimant a Notice of Right to Sue, allowing the claimant to pursue the case in court. If the charge was filed under Title VII or the ADA, the claimant must have a Notice of Right to Sue from EEOC before filing a lawsuit in federal court. Generally, the EEOC must be allowed 180 days to resolve a charge. However, in some cases, the EEOC will issue a Notice of Right to Sue in less than 180 days.

Final Thoughts on Workplace Diversity

Although decades of advocacy and diversity training have had an impact, the results have been mixed. The upside: Deloitte’s research into the current state of inclusion found that 86% of respondents felt they could be themselves most or all of the time at work (Jacobson, 2019). That statistic represents a significant improvement over a relatively short period of time. A survey conducted six years prior found that 61% of “respondents felt they had to hide at least one aspect of who they are” (Deloitte, 2019). At that time, the conclusion was that “most inclusion programs require people to assimilate into the overall corporate culture” and that this need to “cover” directly impacts not only an individual’s sense of self but their commitment to the organization (Matuson, 2013).

On the downside, bias remains a constant, with over 60% of respondents reporting bias in their workplace. Deloitte reports that 64% of employees surveyed “felt they had experienced bias in their workplace during the last year” (Deloitte, 2019). Even more disturbing, 61% of those respondents “felt they experienced bias in the workplace at least once a month.” The percentages of respondents who indicated that they have observed bias in their workplaces during the last year and observe it on a monthly basis are roughly the same at 64% and 63%, respectively.

Research suggests that bias is now more subtle—for example, an act of “microaggression” rather than overt discrimination. It is, however, no less harmful. Deloitte’s 2019 research found that bias impacts not only those who are directly affected, but also those who observe the behavior. Specifically, of those who reported experiencing or observing bias: 86% reported a negative impact on happiness, confidence, and well-being; 70% reported a negative impact on engagement and 68% reported a negative impact on productivity (Deloitte, 2019). Executive coach Laura Gates observes that the price of not addressing corrosive interpersonal behavior is too high. She notes that “if people don’t feel safe, they can’t be creative. If they aren’t creative, they can’t innovate. If they don’t innovate, the business eventually becomes obsolete.”

Although we are generally aware that our perceptions are subjective, we are largely unaware that there can be a disconnect between our conscious thoughts and our unconscious beliefs or biases, primarily a product of socio-cultural conditioning.

Summary

- Understanding diversity can help us to work better in group or team situations and gives us insight into the behavior of an organization.

- The Progressive Era began in the late 1800s and focused on both political and ethical reform.

- External diversity can include but is not limited to, gender, age, ethnicity, and sometimes even religion

- Internal diversity includes individual experiences and backgrounds.

- Equal employment opportunity isn’t just the right thing to do, it’s the law. Specifically, it’s a series of federal laws and amendments designed to eliminate employment discrimination. Employment discrimination laws and regulations are enforced by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), an agency established by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII).

Discussion Questions

- What challenges have you experienced related to diversity in the workplace?

- What policies has your workplace implemented to address diversity in the workplace? How well were those policies received? Were the effective?

- Take a look at the Fortune 500 list and choose any company that has a CEO who is part of a minority group. Then, go to that company’s website and determine the diversity of that company’s senior team. How did this company do in the current year—did they perform better than in the previous two years? Do they have any space on their careers page dedicated to diversity?

Remix/Revisions featured in this section

- Small editing revisions to tailor the content to the Psychology of Human Relations course.

- Remix of Employment Legislation (Introduction to Business – Lumen Learning) and EEO Best Practices, EEO Complaints (Human Resources Management – Lumen Learning) added to Introduction to Social Diversity in the Workplace (Organizational Behavior and Human Relations – Lumen Learning).

- Added images and provided links to locations of images and CC licenses.

- Added doi links to references to comply with APA 7thedition formatting reference manual.

Attributions

CC Licensed Content, Original

Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Stevy Scarbrough. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Employment Legislation. Authored by: Linda Williams Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-introductiontobusiness/chapter/employment-legislation/ License: CC BY 4.0

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Human Resources Management. Authored by: Nina Burokas. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-humanresourcesmgmt/chapter/benefits-of-diversity/ License: CC BY 4.0

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Organizational Behavior. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-organizationalbehavior/chapter/history-of-social-progress/ License: CC BY 4.0

References

29 CFR § 1630.2 – Definitions. (1997). Legal Information Institute Cornell Law School. Retrieved September 12, 2022 from https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/29/1630.2

About the EEOC: Overview. (n.d.). U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Retrieved September 12, 2022 from https://web.archive.org/web/20200430132329/https:/www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/

Best Practices for Employers and Human Resources/EEO Professionals. (2019). U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Accessed September 12, 2022 from https://www.eeoc.gov/initiatives/e-race/best-practices-employers-and-human-resourceseeo-professionals

Buckley, P. & Bachman, D. (2017, July 31). Meet the US workforce of the future: Older, more diverse, and more educated. Deloitte Insights. Retrieved September 11, 2022 from https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/deloitte-review/issue-21/meet-the-us-workforce-of-the-future.html

Clean up corrosive interpersonal dynamics on your team with this system. (n.d.) First Round Review. Retrieved September 12, 2022 from https://review.firstround.com/clean-up-corrosive-interpersonal-dynamics-on-your-team-with-this-system

Diversity defined: What is diversity? (n.d.) Greater Good Magazine. Retrieved September 11, 2022 from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/topic/diversity/definition#what-is-diversity

Diversity defined: Why practice it? (n.d.) Greater Good Magazine. Retrieved September 11, 2022 from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/topic/diversity/definition#why-practice-diversity

Filing a Charge of Discrimination. (n.d.). U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Accessed September 12, 2022 from https://www.eeoc.gov/filing-charge-discrimination

Filing a Discrimination Claim – California. (n.d.) Workplace Fairness. Retrieved September 22, 2022 from https://www.eeoc.gov/filing-charge-discrimination

Hunt, V., Prince, S., Dixon-Fyle, S., & Yee, L. (2018, January 18). Delivering through diversity. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved September 11, 2022 from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/delivering-through-diversity

Jacobson, A. (2019, July 26). Inclusion does not stop workplace bias, Deloitte survey shows. Risk Management Monitor. Retrieved September 12, 2022 from http://www.riskmanagementmonitor.com/inclusion-does-not-stop-workplace-bias-deloitte-survey-shows/

Labor force projections to 2024: The labor force is growing, but slowly. (2015, December). United States Department of Labor: Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved September 11, 2022 from https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2015/article/labor-force-projections-to-2024.htm

Matuson, R. (2013, September 11). Uncovering talent: A new model for inclusion and diversity, Fast Company. Retrieved September 12, 2022 from https://www.fastcompany.com/3016763/uncovering-talent-a-new-model-for-inclusion-and-diversity

Social progress index. (n.d.) Institute for Strategy & Competitiveness – Harvard Business School. Retrieved September 11, 2022 from https://www.isc.hbs.edu/research-areas/Pages/social-progress-index.aspx

Reynolds, K. (n.d.) 13 benefits and challenges of cultural diversity in the workplace. Hult International Business School. Retrieved September 11, 2022 from https://www.hult.edu/blog/benefits-challenges-cultural-diversity-workplace/

Rock, D., Grant, H., & Grey, J. (2016). Diverse teams feel less comfortable — and that’s why they perform better. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved September 11, 2022 from https://hbr.org/2016/09/diverse-teams-feel-less-comfortable-and-thats-why-they-perform-better

Santana, D. (2017, April 24). What is diversity and how do I define it in the social context. Embracing Diversity. Retrieved September 11, 2022 from https://embracingdiversity.us/what-is-diversity-define-social-diversity/

The bias barrier: Allyship, inclusion, and everyday behaviors. (2019). Deloitte. Retrieved September 12, 2022 from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/about-deloitte/inclusion-survey-research-the-bias-barrier.pdf