3.1 Motivation & Goal Setting

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

• Identify the differences between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

• Identify short-term, mid-term, and long-term goals.

• Identify the benefits and rewards of setting goals.

Motivation

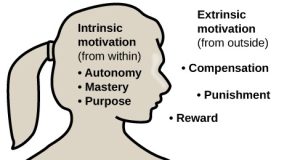

Why do we do the things we do? What motivations underlie our behaviors? Motivation describes the wants or needs that direct behavior toward a goal. In addition to biological motives, motivations can be intrinsic (arising from internal factors) or extrinsic (arising from external factors) (Figure 3.1). Intrinsically motivated behaviors are performed because of the sense of personal satisfaction that they bring, while extrinsically motivated behaviors are performed in order to receive something from others.

Think about why you are pursuing an education. Are you here because you enjoy learning and want to pursue an education to make yourself a more well-rounded individual? If so, then you are intrinsically motivated. However, if you are here because you want to get a college degree to make yourself more marketable for a high-paying career or to satisfy the demands of your parents, then your motivation is more extrinsic in nature.

In reality, our motivations are often a mix of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, but the nature of the mix of these factors might change over time (often in ways that seem counter-intuitive). There is an old adage: “Choose a job that you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life,” meaning that if you enjoy your occupation, work doesn’t seem like . . . well, work. Some research suggests that this isn’t necessarily the case (Daniel & Esser, 1980; Deci, 1972; Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999).

According to this research, receiving some sort of extrinsic reinforcement (i.e., getting paid) for engaging in behaviors that we enjoy leads to those behaviors being thought of as work no longer providing that same enjoyment. As a result, we might spend less time engaging in these reclassified behaviors in the absence of any extrinsic reinforcement. For example, Odessa loves baking, so in her free time, she bakes for fun. Oftentimes, after stocking shelves at her grocery store job, she often whips up pastries in the evenings because she enjoys baking. When a coworker in the store’s bakery department leaves his job, Odessa applies for his position and gets transferred to the bakery department. Although she enjoys what she does in her new job, after a few months, she no longer has much desire to concoct tasty treats in her free time. Baking has become work in a way that changes her motivation to do it (Figure 3.2). What Odessa has experienced is called the overjustification effect—intrinsic motivation is diminished when extrinsic motivation is given. This can lead to extinguishing the intrinsic motivation and creating a dependence on extrinsic rewards for continued performance (Deci et al., 1999).

Other studies suggest that intrinsic motivation may not be so vulnerable to the effects of extrinsic reinforcements, and in fact, reinforcements such as verbal praise might actually increase intrinsic motivation (Arnold, 1976; Cameron & Pierce, 1994). In that case, Odessa’s motivation to bake in her free time might remain high if, for example, customers regularly compliment her baking or cake decorating skills.

These apparent discrepancies in the researchers’ findings may be understood by considering several factors. For one, physical reinforcement (such as money) and verbal reinforcement (such as praise) may affect an individual in very different ways. In fact, tangible rewards (i.e., money) tend to have more negative effects on intrinsic motivation than do intangible rewards (i.e., praise). Furthermore, the expectation of the extrinsic motivator by an individual is crucial: If the person expects to receive an extrinsic reward, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to be reduced. If, however, there is no such expectation, and the extrinsic motivation is presented as a surprise, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to persist (Deci et al., 1999).

In addition, culture may influence motivation. For example, in collectivistic cultures, it is common to do things for your family members because the emphasis is on the group and what is best for the entire group, rather than what is best for any one individual (Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001). This focus on others provides a broader perspective that takes into account both situational and cultural influences on behavior; thus, a more nuanced explanation of the causes of others’ behavior becomes more likely.

In educational settings, students are more likely to experience intrinsic motivation to learn when they feel a sense of belonging and respect in the classroom. This internalization can be enhanced if the evaluative aspects of the classroom are de-emphasized and if students feel that they exercise some control over the learning environment. Furthermore, providing students with activities that are challenging, yet doable, along with a rationale for engaging in various learning activities can enhance intrinsic motivation for those tasks (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009).

Consider Hakim, a first-year law student with two courses this semester: Family Law and Criminal Law. The Family Law professor has a rather intimidating classroom: He likes to put students on the spot with tough questions, which often leaves students feeling belittled or embarrassed. Grades are based exclusively on quizzes and exams, and the instructor posts results of each test on the classroom door. In contrast, the Criminal Law professor facilitates classroom discussions and respectful debates in small groups. The majority of the course grade is not exam-based, but centers on a student-designed research project on a crime issue of the student’s choice. Research suggests that Hakim will be less intrinsically motivated in his Family Law course, where students are intimidated in the classroom setting, and there is an emphasis on teacher-driven evaluations. Hakim is likely to experience a higher level of intrinsic motivation in his Criminal Law course, where the class setting encourages inclusive collaboration and a respect for ideas, and where students have more influence over their learning activities.

Goal Setting

Some people are goal-oriented and seem to easily make decisions that lead to achieving their goals, while others seem just to “go with the flow” and accept what life gives them. While the latter may sound pleasantly relaxed, moving through life without goals may not lead anywhere at all. The fact that you are taking a college course now shows you might be working toward some goal.

A goal is a result we intend to reach mostly through our own actions. Things we do may move us closer to or farther away from that result. Studying moves us closer to success in a difficult course, while sleeping through the final exam may completely prevent reaching that goal. It is fairly obvious in an extreme case, yet a lot of college students do not reach their goal of graduating. The problem may be a lack of commitment to the goal, but often students have conflicting goals. Let us look at some examples of how students may experience conflicting goals.

To help his widowed mother, Juan went to work full time after high school but now, a few years later, he is dissatisfied with the kinds of jobs he has been able to get and has begun taking classes toward an Associate’s Degree in Computer Science in the evenings. He is often tired after work and his mother would like him to spend more time at home, and his girlfriend also wants to spend more time with him. Sometimes he cuts class to visit his mother or spend time with his girlfriend.

In her senior year of college, Becky has just been elected president of her sorority and is excited about planning a major community service project. She knows she should be spending more time on her senior thesis, but she feels her community project may gain her contacts that can help her find a better job after graduation. Besides, the sorority project is a lot more fun, and she is enjoying the esteem of her position. Even if she does not do well on her thesis, she is sure she will pass.

After an easy time in high school, Morgan is surprised their college classes are so hard. They have enough time to study for their first-year courses, but they also have a lot of friends and fun things to do. Sometimes they are surprised to look up from their computer to see it is midnight already, and they have not even started reading that chapter yet. Where does the time go? When they are stressed, however, they cannot study well, so they tell themself they will get up early and read the chapter before class, and then they turn back to their computer to see who is online.

Sachito was successful in cutting back her hours at work to give her more time for her college classes, but it is difficult for her to get much studying done at home. Her husband has been wonderful about taking care of their young daughter, but he cannot do everything, and lately, he has been hinting more about asking her sister to babysit so that the two of them can go out in the evening the way they used to. Lately, when she has had to study on a weekend, he leaves with his friends, and Sachito ends up spending the day with her daughter—and not getting much studying done.

What do these very different students have in common? Each has goals that conflict in one or more ways. Each needs to develop strategies to meet their other goals without threatening their academic success. And all of them have time management issues to work through, three because they feel they do not have enough time to do everything they want or need to do, and one because even though he has enough time, he needs to learn how to manage it more effectively. For all four of them, motivation and attitude will be important as they develop strategies to achieve their goals.

One way to prevent the problems that arise from conflicting goals is to think about all of your goals and priorities and learn ways to manage your time, your studies, and your social life to best reach your goals. Also, consider whether your goals support your core values that you identified in the previous module. You are more likely to achieve a goal that is aligned directly with your values.

Benefits of Goal Setting

Setting goals can turn your dreams into reality. You may have a dream to one day graduate from college, buy a new car, own your own home, travel abroad, etc. Any of these dreams can be broken down into a detailed goal and personal action plan. For example, maybe you want to buy a home 20 years from now. You will need $40,000 as a down payment. That is a lot of money and may not feel achievable. But, if you break that $40,000 into 20 years, that is $2,000 a year. That sounds more manageable. And if we break it down even more, you can buy that house if you save about $165 a month, or $42 a week, or $6 a day! Can you save $6 a day, maybe by packing your lunch instead of the drive-thru? Our big dream is now an achievable, realistic goal.

Setting goals has many benefits. Goal setting allows you to create a plan to focus on your goal, rather than dreaming about the future. It also reduces anxiety and worry. It is much less anxiety-producing to focus on saving $6 a day than it is to save $40,000. It is also motivating because you will be able to measure your progress and successes. At the end of one year, you will have saved $2,000, which will motivate you to keep saving and maybe even increase your saving goal. You will use your time and resources more wisely, often leading to faster and increased results.

As you think about your own goals, think about more than just being a student. You are also a person with your own values, individual needs, desires, hopes, dreams, and plans. Your long-term goals likely include graduation and a career but may also involve social relationships with others, a romantic relationship, family, hobbies or other activities, where and how you live, and so on. While you are a student you may not be actively pursuing all your goals with the same fervor, but they remain goals and are still important in your life. Think about what goals you would like to achieve academically, vocationally (career), financially, personally, physically, spiritually, and socially.

Types of Goals

There are different types of goals, based on time and topic. Below we will discuss the major types of goals that you may set for yourself.

Long-term Goals

Long-term goals may begin with graduating from college and everything you want to happen thereafter. Often your long-term goals (graduating with an associate’s degree) guide your mid-term goals (transferring to a university), and your short-term goals (getting an A on your upcoming exam) become steps for reaching those larger goals. Thinking about your goals in this way helps you realize how even the little things you do every day can keep you moving toward your most important long-term goals. Common long-term goals include things like earning your college degree, owning a home, getting a job in your career area, buying a new car, etc.

Mid-term goals

Mid-term goals involve plans for this school year or your time here at college or goals you want to achieve within the next six months to two years. Mid-term goals are often stepping stones to your long-term goals, but they can also be independent goals. For example, you may have a goal of transferring to university, which is a midterm goal that brings you closer to your long-term goal of getting your Bachelor’s degree. Or, you may have a goal to pay off your credit card debt within the next 12 months or to save for a car that you plan to buy next year. When making mid-term goals related to your long-term goals, make a list of accomplishments that will lead you to your final goal.

Short-term goals

Short-term goals focus on today and the next few days and perhaps weeks. Short-term goals expect accomplishment in a short period of time, such as trying to get a bill paid in the next few days or getting an A on your upcoming exam. The definition of a short-term goal need not relate to any specific length of time. In other words, one may achieve (or fail to achieve) a short-term goal in a day, week, month, year, etc. The time frame for a short-term goal relates to its context in the overall timeline that it is being applied. For instance, one could measure a short-term goal for a month-long project in days; whereas one might measure a short-term goal for someone’s lifetime in months or in years. Often, people define short-term goals in relation to their mid-term or long-term goals.

An example of how short-term and mid-term goals relate to long-term goals is wanting to earn your Bachelor’s degree. If you have a goal of earning your Bachelor’s degree in four years, a mid-term goal is getting your Associate’s Degree and getting accepted to your top choice University in two years. This can be broken down into a series of short-term goals such as your GPA goal for this term, your goal grade on an upcoming exam, and the amount of time you plan to study this weekend. Every long-term goal can be broken down into smaller steps and eventually lead to the question, “what do I have to do today to achieve my goal?” You will make goals in different areas of life and at different times in your life. At this point in your life, academic goals may take precedence but there are also other areas to consider.

- Academic – You clearly already have an academic goal and are actively working on pursuing it. Academic goals may include things like a target GPA, completing your Associate’s Degree or certificate, or transferring to a university. It may also include short-term goals like completing your homework before the weekend.

- Career – At this point, your career goals may be closely linked to your academic goals, such as getting a degree or certificate in your chosen career field. You may also have career goals of gaining experience in your field through internships and work experience.

- Financial – Your financial goals are often tied to your career goals. You may have a salary goal or you may have the goal of saving for a home, a car, or a vacation. You may also have goals to reduce debt and manage your budget.

- Health/Physical – Almost all of us have worked on physical goals. Many people have the goal to lose weight, increasing their exercise, or drinking more water. Other health goals could include establishing a regular sleep schedule, eating more fruits and vegetables, or seeing your doctor regularly. Health goals can also include mental health such as meditating or working to reduce stress and anxiety.

- Social/Relationships – Even though it may feel like it sometimes, your life is more than school and work. You should also establish goals for your social relationships. For example, make a goal to stay in contact with a friend who moved, visit your family every week, or to have a date with your significant other once a week. Your social relationships are a vital part of your life and deserve your attention and focus.

- Spiritual – Many people have religious goals, such as attending church regularly, practicing daily prayer, or joining a church group. Even if you are not religious, you may have spiritual goals such as time alone to meditate.

- Personal/Hobbies – In addition to work and school, you may have hobbies or personal interests that you want to devote time and energy to. Perhaps you have a goal of rebuilding a motorcycle or learning how to knit or sew.

SMART Goals

SMART goals are commonly associated with Peter Drucker’s management by objectives concept. It gives structure and organization to the goal-setting process by establishing defined actions, milestones, objectives and deadlines. Creating SMART goals helps with motivation and focus and keeps you moving forward. Every goal can be made into a SMART goal!

When writing your goals, follow these SMART guidelines (Figure 3.3). You should literally write them down because the act of finding the best words to describe your goals helps you think more clearly about them.

Goals should be SPECIFIC

- What exactly do you want to achieve? Avoid vague terms like “good,” and “more.” The more specific you are, the most likely you are to succeed.

- A specific goal has a much greater chance of being accomplished than a general goal.

- To set a specific goal, answer the six “W” questions:

- Who: Who is involved?

- What: What do I want to accomplish?

- Where: Identify a location.

- When: Establish a time frame.

- Which: Identify requirements and constraints.

- Why: Specific reasons, purpose or benefits of accomplishing the goal.

Example: “I will get a 3.5 GPA this semester so that I can apply to the Surgical Tech Program.”

Goals should be MEASURABLE

- Break your goal down into measurable elements so you have concrete evidence of your progress.

- Using numbers, quantities or time is a good way to ensure measurability.

- To determine if your goal is measurable, ask…

- How much?

- How many?

- How often?

- How will I know when it is accomplished?

Example: “I will study 18 hours per week, 3 hours per day for six days a week.”

Goals should be ATTAINABLE

- A goal should be something to strive for and reach for but something that is achievable and attainable. For example, completing an Associate’s Degree in one year may not be attainable while working full time with a family.

- Ask yourself if you have the time, money, resources and talent to make it happen

- Weigh the effort, time and other costs your goal will take against the benefits and other priorities you have in life.

Example: “I will complete 9 credit hours this semester while working part-time.”

Goals should be REALISTIC

- Your goal should be realistic and relevant. Ask yourself if your goal and timeline is realistic for your life, why is the goal important to you, and what is the objective behind your goal? What makes the goal worthwhile for YOU?

- Why is this goal important to you? (Make sure your goal aligns with your values.)

- What are the benefits and rewards of accomplishing this goal?

- Why will you be able to stay committed in the long-run?

- Is it something that will still be important to you a month or year from now?

Example: “I will become a Surgical Technician in two years to pursue my interests and values in helping others and provide for my family.”

Goals should be TIME-ORIENTED

- Your goal should have a clear deadline to help you stay accountable and motivated.

- Keep the timeline realistic but also a little challenging to create a sense of accountability and avoid procrastination.

- With no deadline, there’s no sense of urgency, which leads to procrastination.

- “Someday,” “soon,” and “eventually” are not deadlines.

- Be specific with each deadline for each step along the way.

Example: “I will complete the draft of my research paper one-week before the deadline.”

Putting Your Goals Into Action

Be certain you want to reach the goal. We are willing to work hard and sacrifice to reach goals that we really care about, ones that support our core values. But we are likely to give up when we encounter obstacles if we do not feel strongly about a goal. If you are doing something only because your parents or someone else wants you to, then it is not your own personal goal—and you may not be motivated to accomplish said goal.

Writing down your goals helps you to organize your thoughts and be clear with your goals, ensuring you meet the SMART goal criteria. When you write your goals, state them positively, stating what you will do rather than what you will not do. When you focus on doing something, that behavior often increases. On the other hand, when you focus on not doing something, that behavior also often increases. For example, if you have a goal to increase your health, you may focus on increasing your water intake to at least 64 ounces per day. This will lead you to think about and drink more water. But, if you focus on not drinking soda, you are likely to think about soda all day and end up drinking more.

After you have written down your goal, post it in a visible place to remind you every day of what it is you are working toward. When you see your goal, ask yourself, “Did my choices today help move more toward my goal? Are my actions supporting my goals?” Being reminded of your goal can help you stay motivated and focused. You should also consider sharing your goal with friends, family or classmates. Sharing your goal with supportive people who care about you will help you stay on track. Share your goal with people you know will be encouraging and cheer you on as you work toward your goal. In return, offer the same support for your friends’ goals and dreams.

Summary

- Motivation describes the wants or needs that direct behavior toward a goal. In addition to biological motives, motivations can be intrinsic (arising from internal factors) or extrinsic (arising from external factors)

- The overjustification effect occurs when intrinsic motivation is diminished due to the addition of extrinsic motivation.

- A goal is a result we intend to reach mostly through our own actions.

- There are different types of goals, based on time (long-term, mid-term, short-term) and topic (academic, career, financial, health/physical, social/relationships, spiritual, personal/hobbies).

Discussion Questions

- Describe an example of something you are intrinsically motivated to do and an example of something you are extrinsically motivated to do in your personal life.

- How might intrinsic and extrinsic motivation be different or similar across cultural groups?

- What process have you used to set goals for yourself in the past? Were you able to meet those goals?

Remix/Revisions featured in this section

- Small editing revisions to tailor the content to the Psychology of Human Relations course.

- Remix of motivation from 1 Motivation (Psychology 2e – Openstax) and goal setting from Chapter 3: Discover Your Values and Goals (Learning Framework: Effective Strategies for College Success – Austin Community College).

- Changed formatting for photos to provide links to locations of images and CC licenses.

- Added doi links to references to comply with APA 7th edition formatting reference manual.

Attributions

CC Licensed Content, Original

Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Stevy Scarbrough. License: CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Discover Your Values and Goals. Authored by: Heather Syrett, Eduardo Garcia, and Marcy May. Provided by: Austin Community College. Located at: https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/25859/overview License: CC BY-NC-SA-4.0

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Psychology 2e. Authored by: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett. Publisher: Openstax. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/11-7-trait-theorists License: CC-BY 4.0

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

SMART_Criteria. Provided by: Wikipedia Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMART_criteria. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

References

Arnold, H. J. (1976). Effects of performance feedback and extrinsic reward upon high intrinsic motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 17, 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(76)90067-2

Cameron, J., & Pierce, W. D. (1994). Reinforcement, reward, and intrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 64, 363–423. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170677

Daniel, T. L., & Esser, J. K. (1980). Intrinsic motivation as influenced by rewards, task interest, and task structure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65, 566–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.65.5.566

Deci, E. L. (1972). Intrinsic motivation, extrinsic reinforcement, and inequity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 22, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0032355

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 627–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627

Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7, 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104318

Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108(2), 291–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.2.291