4.1 Introduction to Personality

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define personality.

- Compare and contrast psychodynamic, learning and cognitive, biological, inherent drives, and sociocultural factors that influence personality.

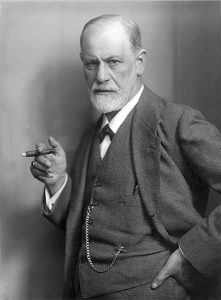

When you first think of personality, what comes to mind? When we refer to certain people as being “personalities,” we usually mean they are famous, people like movie stars or your favorite band. When we describe a person as having “lots of personality,” we usually mean they are outgoing and fun-loving, the kind of person we like to spend time with. But does this tell us anything about personality itself? Although we may think we have an understanding of what personality is, professional psychologists always seek to move beyond what people think they know in order to determine what is actually real or at least as close to real as we can come. In the pursuit of truly understanding personality, however, many personality theorists seem to have been focused on a particularly Western cultural approach that owes much of its history to the pioneering work of Sigmund Freud (Figure 4.1).

Freud trained as a physician with a strong background in biomedical research. He naturally brought his keen sense of observation, a characteristic of any good scientist, into his psychiatric practice. As he worked with his patients, he developed a distinctly medical model: identify a problem, identify the cause of the problem, and treat the patient accordingly. This approach can work quite well, and it has worked wonderfully for medical science, but it has two main weaknesses when applied to the study of personality. First, it fails to address the complexity and uniqueness of individuals, and second, it does not readily lend itself to describing how one chooses to develop a healthy personality.

Quite soon in the history of personality theory, however, there were influential theorists who began to challenge Freud’s perspective. Alfred Adler, although a colleague of Freud’s for a time, began to focus on social interest and an individual’s style of life. Karen Horney challenged Freud’s perspective on the psychology of women, only to later suggest that the issue was more directly related to the oppression of women as a minority, rather than a fundamental difference based on gender. And there were Carl Jung and Carl Rogers, two men profoundly influenced by Eastern philosophy. Consequently, anyone influenced by Jung or Rogers has also been influenced, in part, by Eastern philosophy. What about the rest of the world? Have we taken into account the possibility that there are other, equally valuable and interesting perspectives on the nature of people? Many fields in psychology have made a concerted effort to address cross-cultural issues. By the end of this chapter, you will have a broad understanding of the field of personality, and an appreciation for both what we have in common and what makes us unique, as members of our global community.

Definition and Descriptions of Personality

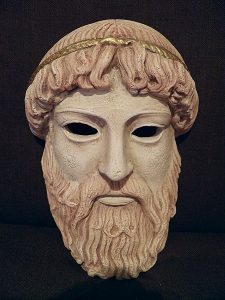

Personality refers to the long-standing traits and patterns that propel individuals to consistently think, feel, and behave in specific ways. Our personality is what makes us unique individuals. Each person has an idiosyncratic pattern of enduring, long-term characteristics and a manner in which they interact with other individuals and the world around them. Our personalities are thought to be long term, stable, and not easily changed. The word personality comes from the Latin word persona. In the ancient world, a persona was a mask worn by an actor (Figure 4.2). While we tend to think of a mask as being worn to conceal one’s identity, the theatrical mask was originally used to either represent or project a specific personality trait of a character. But are our personalities just masks? Freud certainly considered the unconscious mind to be very important, Cattell considered source traits to be more important than surface traits, and Buddhists consider the natural world (including the self) to be an illusion. Adler believed the best way to examine personality is to look at the person’s style of life, and Rogers felt that the only person who could truly understand you is yourself. In order to better understand how some of the different disciplines within the field of psychology contribute to our definition of personality, let’s take a brief look at some of the widely recognized factors that come into play.

Psychodynamic Factors

The very word “psychodynamic” suggests that there are ongoing interactions between different elements of the mind. Sigmund Freud not only offered names for these elements (id, ego, and superego), he proposed different levels of consciousness. Since the unconscious mind was very powerful according to Freud, one of the first and most enduring elements of psychodynamic theory is that we are often unaware of why we think and act the way we do. Add to that the belief that our personality is determined in early childhood, and you can quickly see that psychological problems would be very difficult to treat. Perhaps more importantly, since we are not aware of many of our own thoughts and desires, it would difficult or even impossible for us to choose to change our personality no matter how much we might want to.

Most psychodynamic theorists since Freud have expanded the influences that affect us to include more of the outside world. Those theorists who remained loyal to Freud, typically known as neo-Freudians, emphasized the ego. Since the ego functions primarily in the real world, the individual must take into account the influence of other people involved in their lives. Some theorists who differed significantly from the traditional Freudian perspective, most notably Alfred Adler and Karen Horney, focused much of their theories on cultural influences. Adler believed that social cooperation was essential to the success of each individual (and humanity as a whole), whereas Horney provided an intriguing alternative to Freud’s sexist theories regarding women. Although Horney based her theories regarding women on the cultural standing between men and women in the Victorian era, to a large extent her theory remains relevant today.

Learning and Cognitive Factors

As a species, human beings are distinguished by their highly developed brains. Animals with less-developed nervous systems rely primarily on instinctive behavior, but very little on learning. While the study of animals’ instinctive behavior is fascinating, and led to a shared Nobel Prize for the ethologists Nikolaas Tinbergen, Konrad Lorenz, and Karl von Frisch, animal behavior remains distinctly limited compared to the complex learning and cognitive tasks that humans can readily perform (Beck, 1978; Gould, 1982). Indeed, the profound value of our abilities to think and learn may be best reflected in the fact that, according to Tinbergen’s strict definition of instinct (see Beck, 1978), humans appear not to have any instinctive behavior anymore. Yet we have more than made up for it through our ability to learn, and learning theory and behaviorism became dominant forces in the early years of American psychology (Figure 4.3).

John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner are among the most famous and influential of American psychologists. Learning about their groundbreaking research on classical and operant conditioning is standard fare in psychology courses. More recently, Albert Bandura has enjoyed similar popularity and respect in the field of social learning theory. Anyone who has children knows full well how eagerly they observe us and mimic our actions and speech. An important aspect of the learning perspective is that our personalities may develop as a result of the rewards and/or punishments we receive from others. Consequently, we should be able to shape an individual’s personality in any way we want. Early behaviorists, like Watson, suggested that they could indeed take any child and raise them to be successful in any career they chose for them. Although most parents and teachers try to be a good influence on children, and to set good examples for them, children are often influenced more by their peers. What children find rewarding may not be what parents and teachers think is rewarding. This is why a social-cognitive approach to learning becomes very important in understanding personality development. Social-cognitive theorists, like Bandura, recognize that children interact with their environment, partly determining for themselves what is rewarding or punishing, and then react to the environment in their own unique way.

As suggested by the blend of behaviorism and cognition that Bandura and others proposed, there is a close association between behaviorism and the field of cognitive psychology. Although strict behaviorists rejected the study of unobservable cognitive processes, the cognitive field has actually followed the guidelines of behaviorism with regard to a dispassionate and logical observation of the expression of cognitive processes through an individual’s behavior and what they say. Thus, the ability of human beings to think, reason, analyze, anticipate, etc., leads them to act in accordance with their ideas, rather than simply on the basis of traditional behavioral controls: reward, punishment, or associations with unconditional stimuli. The success of the cognitive approach when applied to therapy, such as the techniques developed by Aaron Beck, has helped to establish cognitive theory as one the most respected areas in the study of personality and abnormal psychology.

Biological Factors

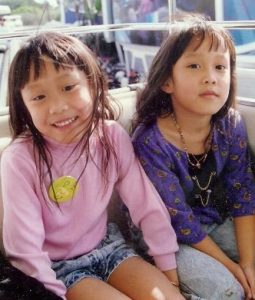

Although humans may not exhibit instinctive behavior, we are still ultimately a product of our biological makeup, our specific DNA pattern. Our individual DNA pattern is unique, unless we happen to be an identical twin, and it not only provides the basis for our learning and cognitive abilities, it also sets the conditions for certain aspects of our character. Perhaps the most salient of these characteristics is temperament, which can loosely be described as the emotional component of our personality. In addition to temperament, twin studies have shown that all aspects of personality appear to be significantly influenced by our genetic inheritance (Bouchard, 1994; Bouchard & McGue, 1990; Bouchard et al., 1990) (Figure 4.4). Even such complex personality variables as well-being, traditionalism, and religiosity have been found to be highly influenced by our genetic make-up (Tellegen et al., 1988; Waller et al., 1990).

Sociobiologists and evolutionary psychologists also emphasize the role of genetics and adaptation over time. Sociobiologists consider how biological factors influence social behavior. For example, they would suggest that men are inclined to prefer multiple sexual partners because men are biologically capable of fathering many children, whereas women would be inclined to favor one successful and established partner, because a woman must physically invest a year or more in each child (a 9-month pregnancy followed by a period of nursing). Similarly, evolutionary psychologists consider how human behavior has been adaptive for our survival. Humans evolved from plant-eating primates; we are not well suited to defend ourselves against large, meat-eating predators. As a group, however, and using our intellect to fashion weapons from sticks and rocks, we were able to survive and flourish over time. Unfortunately, the same adaptive influences that guide the development of each healthy person can, under adverse conditions, lead to dysfunctional behaviors, and consequently, psychological disorders (Millon, 2004).

Inherent Drives

Freud believed that we are motivated primarily by psychosexual impulses, and secondarily by our tendency toward aggression. Certainly, it is necessary to procreate for the species to survive, and elements of aggression are necessary for us to get what we need and to protect ourselves. But this is a particularly dark and somewhat animalistic view of humanity. The humanistic psychologists Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow believed in a positive view of people, they proposed that each of us contains an inherent drive to be the best that we can be, and to accomplish all that we are capable of accomplishing. Rogers and Maslow called this drive self-actualization. Interestingly, this concept is actually thousands of years old, and having spent time in China, Rogers was well aware of Buddhist and Yogic perspectives on the self.

Somewhat related to the humanistic concept of self-actualization, is the existential perspective. Existential theorists, like Rollo May, believe that individuals can be truly happy only when they find some meaning in life. In Eastern philosophical perspectives, coming from Yoga and Buddhism, meaning in life is found by realizing that life is an illusion, that within each of us is the essence of one universal spirit. Indeed, Yoga means “union,” referring to union with God. Thus, we have meaning within us, but the illusion of our life is what distracts us from realizing it.

Sociocultural Influences

Culture can broadly be defined as “everything that people have, think, and do as members of a society” (Ferraro, 2006a), and appears to be as old as the Homo genus itself (the genus of which we, as Homo sapiens, are the current representatives; Haviland et al., 2005). Culture has also been described as the memory of a society (see Triandis & Suh, 2002). Culture is both learned and shared by members of a society, and it is what makes the behavior of an individual understandable to other members of that culture. Everything we do is influenced by culture, from the food we eat to the nature of our personal relationships, and it varies dramatically from group to group. What makes life understandable and predictable within one group may be incomprehensible to another. Despite differences in detail, however, there are a number of cultural universals, those aspects of culture that have been identified in every cultural group that has been examined historically or ethnographically (Murdock, 1945; see also Ferraro, 2006a). Therefore, if we truly want to understand personality theory, we need to know something about the sociocultural factors that may be the same, or that may differ, between groups.

In 1999, Stanley Sue proposed that psychology has systematically avoided the study of cross-cultural factors in psychological research. This was not because psychologists themselves are biased, but rather, it was due to an inherent bias in the nature of psychological research (for commentaries see also Tebes, 2000; Guyll & Madon, 2000; and Sue, 2000). Although some may disagree with the arguments set forth in Sue’s initial study, it is clear that the vast majority of research has been conducted here in America, primarily by American college professors studying American psychology students. And the history of our country clearly identifies most of those individuals, both the professors and the students, as White, middle- to upper-class men. The same year, Lee et al. (1999) brought together a collection of multicultural perspectives on personality, with the individual chapters written by a very diverse group of authors. In both the preface and their introductory chapter, the editors emphasize that neither human nature nor personality can be separated from culture. And yet, as suggested by Sue (1999), they acknowledge the general lack of cross-cultural or multicultural research in the field of personality.

Times have begun to change, however. In 2002, the American Psychological Association (APA) adopted a policy entitled “Guidelines on Multicultural Education, Training, Research, Practice, and Organizational Change for Psychologists. The year 2002 also saw a chapter in the prestigious Annual Review of Psychology on how culture influences the development of personality (Triandis & Suh, 2002). In a fascinating article on whether psychology actually matters in our lives, former APA president and renowned social psychologist Philip Zimbardo (2004) identified the work of Kenneth and Mamie Clark on prejudice and discrimination, which was presented to the United States Supreme Court during the Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, KS case (which led to the end of school segregation in America) (Figure 4.5) as one of the most significant impacts on American life that psychology has contributed to directly (see also Benjamin & Crouse, 2002; Keppel, 2002; Pickren & Tomes, 2002). Finally, an examination of American Psychologist (the principle journal of APA) and Psychological Science (the principle journal of the American Psychological Society) since the year 2000 reveals studies demonstrating the importance of cross-cultural research in many areas of psychology. So, although personality theorists, and the field of psychology in general, have been somewhat slow to address cross-cultural and diversity issues, in more recent years psychologists appear to be rapidly gaining a greater appreciation of the importance of studying human diversity in all its forms.

One of the primary goals of this chapter is to incorporate different cultural perspectives into our study of personality theory, to take more of a global perspective than has traditionally been done. Why is this important? The United States of America has less than 300 million people. India has nearly 1 billion people, and China has over 1 billion people. So, two Asian countries alone have nearly 7 times as many people as the United States. How can we claim to be studying personality if we have not taken into account the vast majority of people in the world? Of course, we have not entirely ignored these two particular countries, because two of the most famous personality theorists spent time in these countries when they were young. Carl Jung spent time in India, and his theories were clearly influenced by ancient Vedic philosophy, and Carl Rogers spent time in China while studying to be a minister. So, it is possible to draw connections between Yoga, Buddhism, psychodynamic theory, and humanistic psychology. Sometimes this will involve looking at differences between cultures, and other times it will focus on similarities. At the end of this chapter, you will have gained a sense of the diversity of personality and personality theory, and the connections that tie all of us together.

Some Basic Questions Common to All Areas of Personality Theory

In addition to the broad perspectives described above, there are a number of philosophical questions that help to bring the nature of personality into perspective. Thinking about how these questions are answered by each theory can help us to compare and contrast the different theories.

Is our personality inherited, or are we products of our environment?

This is the classic debate on nature vs. nurture. Are we born with a given temperament, with a genetically determined style of interacting with others, certain abilities, with various behavioral patterns that we cannot even control? Or are we shaped by our experiences, by learning, thinking, and relating to others? Many psychologists today find this debate amusing, because no matter what area of psychology you study, the answer is typically both. We are born with a certain range of possibilities determined by our DNA. We can be a certain height, have a certain IQ, be shy or outgoing, we might be Black, Asian, White or Hispanic, etc. because of who we are genetically. However, the environment can have a profound effect on how our genetic make-up is realized. For example, a child with both parents over six feet in height, will likely have inherited genes to also be over six feet in height. However, while the child was growing up, their family was very poor and they were malnourished, stunting their growth. The end result might be that this child is several inches shorter than their parents. Our genetic make-up provides a range of possibilities for our life, and the environment in which we grow determines where exactly we fall within that range.

Are we unique, or are there common types of personality?

Many people want to believe that they are special and truly unique, and they tend to reject theories that try to categorize individuals. However, if personality theories were unique to each person, we could never possibly cover all of the theories. In order to understand and compare people, personality theorists need to consider that there are common aspects of personality. It is up to each of us to decide whether we are still willing to find what is unique and special about each separate person.

Which is more important, the past, present, or future?

Many theorists, particularly psychodynamic theorists, consider personality to be largely determined at an early age. Similarly, those who believe strongly in the genetic determination of personality would consider many factors set even before birth. But what prospects for growth does this allow, can people change or choose a new direction in their life? Cognitive and behavioral theorists focus on specific thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors that are influencing our daily lives, whereas existential theorists search for meaning in our lives. Other theorists, such as the humanists and those who favor the spiritually-oriented perspectives we will examine, consider the future to be primary in our goals and aspirations. Self-actualization is something we can work toward. Indeed, it may be an inherent drive.

Do we have free will, or is our behavior determined?

Although this question seems similar to the previous one, it refers more to whether we consciously choose the path we take in life as compared to whether our behavior is specifically determined by factors beyond our control. We already mentioned the possibility of genetic factors above, but there might also be unconscious factors and stimuli in our environment. Certainly, humans rely on learning for much of what we do in life, so why not for developing our personalities? Though some students do not want to think of themselves as simply products of reinforcement and punishment (i.e., operant conditioning) or the associations formed during classical conditioning (anyone have a phobia?), what about the richness of observational learning? Still, exercising our will and making sound choices seems far more dignified to many people. Is it possible to develop our will, to help us make better choices and follow through on them? Yes, according to William James, America’s foremost psychologist. James considered our will to be of great importance, and he included chapters on the will in two classic books; Psychology: Briefer Course, published in 1892 and Talks to Teachers on Psychology and to Students on Some of Life’s Ideals, which was published in 1899. James not only thought about the importance of the will, he recommended exercising it. In Talks to Teachers…, he sets forth the following responsibility for teachers of psychology:

But let us now close in a little more closely on this matter of the education of the will. Your task is to build up a character in your pupils; and a character, as I have so often said, consists in an organized set of habits of reaction. Now of what do such habits of reaction themselves consist? They consist They consist of tendencies to act characteristically when certain ideas possess us, and to refrain characteristically when possessed by other ideas (pg. 816).

Summary

- Personality refers to the long-standing traits and patterns that propel individuals to consistently think, feel, and behave in specific ways. Our personality is what makes us unique individuals.

- A wide variety of theoretical perspectives influence how psychologists view personality, including psychodynamic factors, learning/cognitive factors, biological factors, inherent drives, and sociocultural influences.

- The various personality theories also address questions related to nature vs. nurture, whether individuals are unique or whether there are types of personality common to all people, the relative importance of the past, present, and future, and the significance of free will.

Discussion Questions

- How similar or different, is your personality to your parents, grandparents, siblings, etc.? Do you think that your environment (community, friends, media, etc.) have been more influential to your personality than your genetics?

- Do you feel that you are driven to accomplish something great, or to find some particular meaning in life? Do you believe that there might be pathways to guide you, such as spiritual or religious pathways?

- Do you notice cultural differences around you every day, or do you live in a small community where everyone is very much the same? What sort of challenges do you face as a result of cultural differences, either because you deal with them daily or because you have little opportunity to experience them?

Remix/Revisions Featured in this Section

- Small editing revisions to tailor the content to the Psychology of Human Relations course.

- Changed formatting for photos to provide links to locations of images and CC licenses.

- Added doi links to references to comply with APA 7th edition formatting reference manual.

Attributions

CC Licensed Content, Original

Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Stevy Scarbrough. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Personality Theory. Authored by: Mark Kelland. Located at: https://www.oercommons.org/authoring/22859-personality-theory/1/view License: CC-BY-NC-SA

References

American Psychological Association. (2002). Guidelines on Multicultural Education, Training, Research, Practice, and Organizational Change for Psychologists. Retreived on 07/28/22 from https://www.apa.org/about/policy/multicultural-guidelines-archived.pdf

Beck, R. C. (1978). Motivation: Theories and principles. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Benjamin, Jr., L. T. & Crouse, E. M. (2002). The American Psychological Association’s response to Brown v. Board of Education: The case of Kenneth B. Clark. American Psychologist, 57, 38-50. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.1.38

Bouchard, Jr., T. J. (1994). Genes, environment, and personality. Science, 264, 1700-1701. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.8209250

Bouchard, Jr., T. J. & McGue, M. (1990). Genetic and rearing environmental influences on adult personality: An analysis of adopted twins reared apart. Journal of Personality, 58, 263-292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00916.x

Bouchard, Jr., T. J., Lykken, D. T., McGue, M., Segal, N. L., & Tellegen, A. (1990). Sources of human psychological differences: The Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart. Science, 250, 223-228. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.2218526

Ferraro, G. (2006). Cultural anthropology: An applied perspective, 6th Ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

Gould, J. L. (1982). Ethology: The mechanisms and evolution of behavior. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Guyll, M. & Madon, S. (2000). Ethnicity research and theoretical conservatism. American Psychologist, 55, 1509-1510. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.12.1509

Haviland, W. A., Prins, H. E. L., Walrath, D. & McBride, B. (2005). Anthropology: The Human Challenge (11th Ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

Keppel, B. (2002). Kenneth B. Clark in the patterns of American culture. American Psychologist, 57, 29-37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.1.29

Lee, Y.-T., McCauley, C. R., & Draguns, J. G. (Eds.). (1999) Personality and person perception across cultures. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Millon, T. (2004). Masters of the Mind: Exploring the story of mental illness from ancient times to the new millennium. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons.

Murdock, G. P. (1945). The common denominator of cultures. In R. Linton (Ed.), The science of man in the world crisis (pp. 122-142). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Pickren, W. E. & Tomes, H. (2002). The legacy of Kenneth B. Clark to the APA: The Board of Social and Ethical Responsibility for Psychology. American Psychologist, 57, 51-59. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.1.51

Sue, S. (1999). Science, ethnicity, and bias: Where have we gone wrong? American Psychologist, 54, 1070-1077. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.12.1070

Sue, S. (2000). The practice of psychological science. American Psychologist, 55, 1510-1511. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.12.1510

Tebes, J. K. (2000). External validity and scientific psychology. American Psychologist, 55, 1508-1509. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.12.1508

Tellegen, A., Lykken, D. T., Bouchard, T. J., Wilcox, K. J., Segal, N. L., & Rich, S. (1988). Personality similarity in twins reared apart and together. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1031-1039. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1031

Triandis, H. C. & Suh, E. M. (2002). Cultural influences on personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 133-160. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135200

Waller, N. G., Kojetin, B. A., Bouchard, T. J., Lykken, D. T., & Tellegen, A. (1990). Genetic and environmental influences on religious interests, attitudes, and values. Psychological Science, 1, 138-142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1990.tb00083.x

Zimbardo, P. G. (2004). Does psychology make a significant difference in our lives? American Psychologist, 59, 339-351. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.5.339