8.1 What is Stress?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe various definitions of stress, including the difference between stimulus-based and response-based stress and good stress and bad stress.

- Describe different types of possible stressors.

- Differentiate between good stress and bad stress.

You are exhausted. When you get home, you drop your work bag and realize you forgot to send an e-mail to your supervisor about an upcoming project. You groan as you run downstairs to your computer. The clock says 7:03 p.m. and you feel like you haven’t had a minute to yourself since this morning. As you think about your day, you realize, you haven’t! It is your company’s busy time so the last few days have been booked with meetings and a huge project, with a Friday deadline. You send the e-mail, make a quick sandwich for dinner, and sit back down at your computer. You are hoping to get a few more things done on the project before tomorrow morning. As you work, you receive text messages from a colleague who is working on one portion of the project. You answer her texts and think about checking Facebook but decide against it as you just have too much to do. Your status update meeting is at 9 a.m. and you want to be able to show extensive progress on the project. At 10:30 p.m., you shut your computer, go to bed, and have a hard time falling asleep because you are thinking about everything you need to finish this week.

Does this sound like someone you know? Many people today are struggling with the ability to manage time with so much work/school to do and personal/family lives to manage. Technology has certainly made working longer hours easier, as we are always in touch with the office. What we can tend to forget is the importance of managing our stress levels so we can function more effectively. In this situation, having no free time during the day may work for a few days but isn’t a healthy long-term solution. This chapter will discuss some types of stress, the effects of stress, and what you can do to reduce stress.

You probably know exactly what it’s like to feel stress, but what you may not know is that it can objectively influence your health. Answers to questions like, “How stressed do you feel?” or “How overwhelmed do you feel?” can predict your likelihood of developing both minor illnesses as well as serious problems like future heart attack (Cohen, Janicki-Deverts, & Miller, 2007).

The term stress as it relates to the human condition first emerged in scientific literature in the 1930s, but it did not enter the popular vernacular until the 1970s (Lyon, 2012). Today, we often use the term loosely in describing a variety of unpleasant feeling states; for example, we often say we are stressed out when we feel frustrated, angry, conflicted, overwhelmed, or fatigued. Despite the widespread use of the term, stress is a fairly vague concept that is difficult to define with precision.

Researchers have had a difficult time agreeing on an acceptable definition of stress. Some have conceptualized stress as a demanding or threatening event or situation (e.g., a high-stress job, overcrowding, and long commutes to work). Such conceptualizations are known as stimulus-based definitions because they characterize stress as a stimulus that causes certain reactions. Stimulus-based definitions of stress are problematic, however, because they fail to recognize that people differ in how they view and react to challenging life events and situations. For example, a conscientious student who has studied diligently all semester would likely experience less stress during final exams week than would a less responsible, unprepared student.

Others have conceptualized stress in ways that emphasize the physiological responses that occur when faced with demanding or threatening situations (e.g., increased arousal). These conceptualizations are referred to as response-based definitions because they describe stress as a response to environmental conditions. For example, the endocrinologist Hans Selye, a famous stress researcher, once defined stress as the “response of the body to any demand, whether it is caused by, or results in, pleasant or unpleasant conditions” (Selye, 1976, p. 74). Selye’s definition of stress is response-based in that it conceptualizes stress chiefly in terms of the body’s physiological reaction to any demand that is placed on it. Neither stimulus-based nor response-based definitions provide a complete definition of stress. Many of the physiological reactions that occur when faced with demanding situations (e.g., accelerated heart rate) can also occur in response to things that most people would not consider to be genuinely stressful, such as receiving unanticipated good news: an unexpected promotion or raise.

A useful way to conceptualize stress is to view it as a process whereby an individual perceives and responds to events that they appraise as overwhelming or threatening to their well-being (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). A critical element of this definition is that it emphasizes the importance of how we appraise—that is, judge—demanding or threatening events (often referred to as stressors); these appraisals, in turn, influence our reactions to such events. Two kinds of appraisals of a stressor are especially important in this regard: primary and secondary appraisals. A primary appraisal involves judgment about the degree of potential harm or threat to well-being that a stressor might entail. A stressor would likely be appraised as a threat if one anticipates that it could lead to some kind of harm, loss, or other negative consequence; conversely, a stressor would likely be appraised as a challenge if one believes that it carries the potential for gain or personal growth. For example, an employee who is promoted to a leadership position would likely perceive the promotion as a much greater threat if they believed the promotion would lead to excessive work demands than if they viewed it as an opportunity to gain new skills and grow professionally. Similarly, a college student on the cusp of graduation may face the change as a threat or a challenge (Figure 8.1).

The perception of a threat triggers a secondary appraisal, a judgment of the options available to cope with a stressor, as well as perceptions of how effective such options will be (Lyon, 2012) (Figure 8.2). As you may recall from what you learned about self-efficacy, an individual’s belief in their ability to complete a task is important (Bandura, 1994). A threat tends to be viewed as less catastrophic if one believes something can be done about it (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Imagine that two middle-aged people, Robin and Madhuri, perform breast self-examinations one morning and each notices a lump on the lower region of their left breast. Although both view the breast lump as a potential threat (primary appraisal), their secondary appraisals differ considerably. In considering the breast lump, some of the thoughts racing through Robin’s mind are, “Oh my God, I could have breast cancer! What if the cancer has spread to the rest of my body and I cannot recover? What if I have to go through chemotherapy? I’ve heard that experience is awful! Oh, this is just horrible…I can’t deal with it!” On the other hand, Madhuri thinks, “Hmm, this may not be good. Although most times these things turn out to be benign, I need to have it checked out. If it turns out to be breast cancer, there are doctors who can take care of it because the medical technology today is quite advanced. I’ll have a lot of different options, and I’ll be just fine.” Clearly, Robin and Madhuri have different outlooks on what might turn out to be a very serious situation. As such, Robin would clearly experience greater stress than would Madhuri.

To be sure, some stressors are inherently more stressful than others in that they are more threatening and leave less potential for variation in cognitive appraisals (e.g., objective threats to one’s health or safety). Nevertheless, appraisal will still play a role in augmenting or diminishing our reactions to such events (Everly & Lating, 2002).

If a person appraises an event as harmful and believes that the demands imposed by the event exceed the available resources to manage or adapt to it, the person will subjectively experience a state of stress. In contrast, if one does not appraise the same event as harmful or threatening, they are unlikely to experience stress. According to this definition, environmental events trigger stress reactions by the way they are interpreted and the meanings they are assigned. In short, stress is largely in the eye of the beholder: it’s not so much what happens to you as it is how you respond (Selye, 1976).

Stressors

For an individual to experience stress, they must first encounter a potential stressor. In general, stressors can be placed into one of two broad categories: chronic and acute. Chronic stressors include events that persist over an extended period of time, such as caring for a parent with dementia, long-term unemployment, or imprisonment. Acute stressors involve brief focal events that sometimes continue to be experienced as overwhelming well after the event has ended, such as falling on an icy sidewalk and breaking your leg (Cohen, Janicki-Deverts, & Miller, 2007). Whether chronic or acute, potential stressors come in many shapes and sizes. They can include major traumatic events, significant life changes, daily hassles, as well as other situations in which a person is regularly exposed to threat, challenge, or danger.

Traumatic Events

Some stressors involve traumatic events or situations in which a person is exposed to actual or threatened death or serious injury. Stressors in this category include exposure to military combat, threatened or actual physical assaults (e.g., physical attacks, sexual assault, robbery, childhood abuse), terrorist attacks, natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes, floods, hurricanes), and automobile accidents. Men, People of Color, and individuals in lower socioeconomic status (SES) groups report experiencing a greater number of traumatic events than do women, Whites, and individuals in higher SES groups (Hatch & Dohrenwend, 2007). Some individuals who are exposed to stressors of extreme magnitude develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a chronic stress reaction characterized by experiences and behaviors that may include intrusive and painful memories of the stressor event, jumpiness, persistent negative emotional states, detachment from others, angry outbursts, and avoidance of reminders of the event (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013).

Significant Life Changes

Most stressors that we encounter are not nearly as intense as the ones described above. Many potential stressors we face involve events or situations that require us to make changes in our ongoing lives and require time as we adjust to those changes. Examples include death of a close family member, marriage, divorce, and moving (Figure 8.3).

In the 1960s, psychiatrists Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe wanted to examine the link between life stressors and physical illness, based on the hypothesis that life events requiring significant changes in a person’s normal life routines are stressful, whether these events are desirable or undesirable. They developed the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS), consisting of 43 life events that require varying degrees of personal readjustment (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). Many life events that most people would consider pleasant (e.g., holidays, retirement, marriage) are among those listed on the SRRS; these are examples of eustress. Holmes and Rahe also proposed that life events can add up over time, and that experiencing a cluster of stressful events increases one’s risk of developing physical illnesses.

In developing their scale, Holmes and Rahe asked 394 participants to provide a numerical estimate for each of the 43 items; each estimate corresponded to how much readjustment participants felt each event would require (Table 8.1). These estimates resulted in mean value scores for each event—often called life change units (LCUs) (Rahe, McKeen, & Arthur, 1967). The numerical scores ranged from 11 to 100, representing the perceived magnitude of life change each event entails. Death of a spouse ranked highest on the scale with 100 LCUs, and divorce ranked second highest with 73 LCUs. In addition, personal injury or illness, marriage, and job termination also ranked highly on the scale with 53, 50, and 47 LCUs, respectively. Conversely, change in residence (20 LCUs), change in eating habits (15 LCUs), and vacation (13 LCUs) ranked low on the scale (Table 1). Minor violations of the law ranked the lowest with 11 LCUs. To complete the scale, participants checked yes for events experienced within the last 12 months. LCUs for each checked item are totaled for a score quantifying the amount of life change. Agreement on the amount of adjustment required by the various life events on the SRRS is highly consistent, even cross-culturally (Holmes & Masuda, 1974).

| Life Event | Life Change Units |

|---|---|

| Death of a close family member | 63 |

| Personal injury or illness | 53 |

| Dismissal from work | 47 |

| Change in financial state | 38 |

| Change to different line of work | 36 |

| Outstanding personal achievement | 28 |

| Beginning or ending school | 26 |

| Change in living conditions | 25 |

| Change in working hours or conditions | 20 |

| Change in residence | 20 |

| Change in schools | 20 |

| Change in social activities | 18 |

| Change in sleeping habits | 16 |

| Change in eating habits | 15 |

| Minor violation of the law | 11 |

Extensive research has demonstrated that accumulating a high number of life change units within a brief period of time (one or two years) is related to a wide range of physical illnesses (even accidents and athletic injuries) and mental health problems (Monat & Lazarus, 1991; Scully, Tosi, & Banning, 2000). In an early demonstration, researchers obtained LCU scores for U.S. and Norwegian Navy personnel who were about to embark on a six-month voyage. A later examination of medical records revealed positive (but small) correlations between LCU scores prior to the voyage and subsequent illness symptoms during the ensuing six-month journey (Rahe, 1974). In addition, people tend to experience more physical symptoms, such as backache, upset stomach, diarrhea, and acne, on specific days in which self-reported LCU values are considerably higher than normal, such as the day of a family member’s wedding (Holmes & Holmes, 1970).

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) provides researchers a simple, easy-to-administer way of assessing the amount of stress in people’s lives, and it has been used in hundreds of studies (Thoits, 2010). Despite its widespread use, the scale has been subject to criticism. First, many of the items on the SRRS are vague; for example, death of a close friend could involve the death of a long-absent childhood friend that requires little social readjustment (Dohrenwend, 2006). In addition, some have challenged its assumption that undesirable life events are no more stressful than desirable ones (Derogatis & Coons, 1993). However, most of the available evidence suggests that, at least as far as mental health is concerned, undesirable or negative events are more strongly associated with poor outcomes (such as depression) than are desirable, positive events (Hatch & Dohrenwend, 2007). Perhaps the most serious criticism is that the scale does not take into consideration respondents’ appraisals of the life events it contains. As you recall, appraisal of a stressor is a key element in the conceptualization and overall experience of stress. Being fired from work may be devastating to some but a welcome opportunity to obtain a better job for others. The SRRS remains one of the most well-known instruments in the study of stress, and it is a useful tool for identifying potential stress-related health outcomes (Scully et al., 2000).

Daily Hassles

Potential stressors do not always involve major life events. Daily hassles—the minor irritations and annoyances that are part of our everyday lives (e.g., rush hour traffic, lost keys, obnoxious coworkers, inclement weather, arguments with friends or family)—can build on one another and leave us just as stressed as significant life changes (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1981).

Researchers have demonstrated that the frequency of daily hassles is actually a better predictor of both physical and psychological health than are life change units. In a well-known study of San Francisco residents, the frequency of daily hassles was found to be more strongly associated with physical health problems than were life change events (DeLongis, Coyne, Dakof, Folkman, & Lazarus, 1982). In addition, daily minor hassles, especially interpersonal conflicts, often lead to negative and distressed mood states (Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Schilling, 1989). Cyber hassles that occur on social media may represent a modern and evolving source of stress. In one investigation, social media stress was tied to loss of sleep in adolescents, presumably because ruminating about social media caused a physiological stress response that increased arousal (van der Schuur, Baumgartner, & Sumter, 2018). Clearly, daily hassles can add up and take a toll on us both emotionally and physically.

Is There Good Stress?

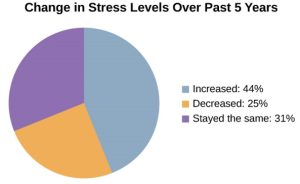

Stress is everywhere and has been on the rise over the last several years (Figure 8.5). Each of us is acquainted with stress—some are more familiar than others. In many ways, stress feels like a load you just can’t carry—a feeling you experience when, for example, you have to drive somewhere in a blizzard, when you wake up late the morning of an important job interview, when you run out of money before the next pay period, and before taking an important exam for which, you realize you are not fully prepared.

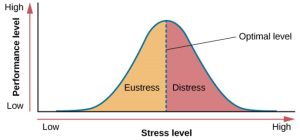

Although stress carries a negative connotation, at times it may be of some benefit. Stress can motivate us to do things in our best interests, such as study for exams, visit the doctor regularly, exercise, and perform to the best of our ability at work. Indeed, Selye (1974) pointed out that not all stress is harmful. He argued that stress can sometimes be a positive, motivating force that can improve the quality of our lives. This kind of stress, which Selye called eustress (from the Greek eu = “good”), is a good kind of stress associated with positive feelings, optimal health, and performance. A moderate amount of stress can be beneficial in challenging situations. For example, students may experience beneficial stress before a major exam. Research shows that moderate stress can enhance both immediate and delayed recall of educational material. Participants in one study who memorized a scientific text passage showed improved memory of the passage immediately after exposure to a mild stressor as well as one day following exposure to the stressor (Hupbach & Fieman, 2012).

Increasing one’s level of stress will cause performance to change in a predictable way. As stress increases, so do performance and general well-being (eustress); when stress levels reach an optimal level (the highest point of the curve), performance reaches its peak (Figure 8.6). A person at this stress level will feel fully energized, focused, and can work with minimal effort and maximum efficiency. But when stress exceeds this optimal level, it is no longer a positive force—it becomes excessive and debilitating, or what Selye termed distress (from the Latin dis = “bad”). People who reach this level of stress feel burned out; they are fatigued, exhausted, and their performance begins to decline. If the stress remains excessive, health may begin to erode as well (Everly & Lating, 2002). A good example of distress is severe test anxiety. When students are feeling very stressed about a test, negative emotions combined with physical symptoms may make concentration difficult, thereby negatively affecting test scores.

Summary

- Stress is a process whereby an individual perceives and responds to events appraised as overwhelming or threatening to one’s well-being.

- Stressors can be chronic (long term) or acute (short term), and can include traumatic events, significant life changes, daily hassles, and situations in which people are frequently exposed to challenging and unpleasant events.

- Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe developed the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) to measure stress by assigning a number of life change units to life events that typically require some adjustment, including positive events.

- Many potential stressors also include daily hassles, which are minor irritations and annoyances that can build up over time.

- Stress can be positive (eustress) or negative (distress).

Discussion Questions

- Discuss an example of a situation or event that could be appraised as either threatening or challenging.

- Compare and contrast examples of chronic stress and acute stress. Discuss an example of when chronic stress might contribute to more negative effects on your life than acute stress. Discuss an example of when acute stress might contribute to more negative effects on your life than chronic stress.

- Describe an example of how a daily hassle could contribute to chronic stress.

Remix/Revisions featured in this section

- Small editing revisions to tailor the content to the Psychology of Human Relations course.

- Remix of combining sections What is Stress and Stressors (Psychology 2e – Openstax).

- Added and changed some images as well as changed formatting for photos to provide links to locations of images and CC licenses.

- Added doi links to references to comply with APA 7th edition formatting reference manual.

Attributions

CC Licensed Content, Original

Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Stevy Scarbrough. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Psychology 2e Authored by: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, and Marilyn D. Lovett. Published by: Openstax Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/14-introduction License: CC BY 4.0

References

American Psychological Association, “Stress: The Different Kinds,” accessed February 15, 2012, http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/stress-kinds.aspx

American Psychological Association, “Stress: The Different Kinds,” accessed February 15, 2012, http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/stress-kinds.aspx

American Psychological Association, “Stress Won’t Go Away?” accessed February 15, 2012, http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/chronic-stress.aspx

American Psychological Association, “Understanding Chronic Stress,” accessed February 15, 2012, http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/understanding-chronic-stress.aspx

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author.

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachandran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71–81). Academic Press.

Bolger, N., DeLongis, A., Kessler, R. C., & Schilling, E. A. (1989). Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 808–818. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.808

Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., & Miller, G. E. (2007). Psychological stress and disease. Journal of the American Medical Association, 298(14), 1685–1687. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.14.1685

DeLongis, A., Coyne, J. C., Dakof, G., Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1982). Relationship of daily hassles, uplifts, and major life events to health status. Health Psychology, 1(2), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.1.2.119

Derogatis, L. R., & Coons, H. L. (1993). Self-report measures of stress. In L. Goldberger & S. Breznitz (Eds.), Handbook of stress: Theoretical and clinical aspects (2nd ed., pp. 200–233). Free Press.

Dohrenwend, B. P. (2006). Inventorying stressful life events as risk factors for psychopathology: Toward resolution of the problem of intracategory variability. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 477–495. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.477

Everly, G. S., & Lating, J. M. (2002). A clinical guide to the treatment of the human stress response (2nd ed.). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishing.

Hatch, S. L., & Dohrenwend, B. P. (2007). Distribution of traumatic and other stressful life events by race/ethnicity, gender, SES, and age: A review of the research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40, 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9134-z

Holmes, T. S., & Holmes, T. H. (1970). Short-term intrusions into the life style routine. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 14(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(70)90022-X

Holmes, T. H., & Masuda, M. (1974). Life change and illness susceptibility. In B. S. Dohrenwend & B. P. Dohrenwend (Eds.), Stressful life events: Their nature and effects (pp. 45–72). John Wiley & Sons.

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4

Hupbach, A., & Fieman, R. (2012). Moderate stress enhances immediate and delayed retrieval of educationally relevant material in healthy young men. Behavioral Neuroscience, 126(6), 819–825. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030489

Kanner, A. D., Coyne, J. C., Schaefer, C., & Lazarus, R. S. (1981). Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. Journal of behavioral medicine, 4(1), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00844845

Lazarus, R. P., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

Lyon, B. L. (2012). Stress, coping, and health. In V. H. Rice (Ed.), Handbook of stress, coping, and health: Implications for nursing research, theory, and practice (2nd ed., pp. 2–20). Sage.

Monat, A., & Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Stress and coping: An anthology (3rd ed.). Columbia University Press.

Rahe, R. H. (1974). The pathway between subjects’ recent life changes and their near-future illness reports: Representative results and methodological issues. In B. S. Dohrenwend & B. P. Dohrenwend (Eds.), Stressful life events: Their nature and effects (pp. 73–86). Wiley & Sons.

Rahe, R. H., McKean, J. D., Jr., & Arthur, R. J. (1967). A longitudinal study of life-change and illness patterns. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 10(4), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(67)90072-4

Scully, J. A., Tosi, H., & Banning, K. (2000). Life event checklists: Revisiting the Social Readjustment Rating Scale after 30 years. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60(6), 864–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131640021970952

Selye, H. (1976). The stress of life (Rev. ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Thoits P. A. (2010). Stress and health: major findings and policy implications. Journal of health and social behavior, 51 Suppl, S41–S53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383499

van der Schuur, W. A., Baumgartner, S. E., & Sumter, S. R. (2019). Social media use, social media stress, and sleep: Examining cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships in adolescents. Health Communication, 34(5), 552–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1422101