8.2 Coping with Stress

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define coping and differentiate between problem-focused and emotion-focused coping

- Describe the importance of perceived control in our reactions to stress

- Explain how social support is vital in health and longevity

As we learned in the previous section, stress—especially if it is chronic—takes a toll on our bodies and can have enormously negative health implications. When we experience events in our lives that we appraise as stressful, it is essential that we use effective coping strategies to manage our stress. Coping refers to mental and behavioral efforts that we use to deal with problems relating to stress.

Coping Styles

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) distinguished two fundamental kinds of coping: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. In problem-focused coping, one attempts to manage or alter the problem that is causing one to experience stress (i.e., the stressor). Problem-focused coping strategies are similar to strategies used in everyday problem-solving: they typically involve identifying the problem, considering possible solutions, weighing the costs and benefits of these solutions, and then selecting an alternative (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). As an example, suppose Bradford receives a midterm notice that he is failing statistics class. If Bradford adopts a problem-focused coping approach to managing his stress, he would be proactive in trying to alleviate the source of the stress. He might contact his professor to discuss what must be done to raise his grade, he might also decide to set aside two hours daily to study statistics assignments, and he may seek tutoring assistance. A problem-focused approach to managing stress means we actively try to do things to address the problem.

Emotion-focused coping, in contrast, consists of efforts to change or reduce the negative emotions associated with stress. These efforts may include avoiding, minimizing, or distancing oneself from the problem, or positive comparisons with others (“I’m not as bad off as she is”), or seeking something positive in a negative event (“Now that I’ve been fired, I can sleep in for a few days”). In some cases, emotion-focused coping strategies involve reappraisal, whereby the stressor is construed differently (and somewhat self-deceptively) without changing its objective level of threat (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). For example, a person sentenced to federal prison who thinks, “This will give me a great chance to network with others,” is using reappraisal. If Bradford adopted an emotion-focused approach to managing his midterm deficiency stress, he might watch a comedy movie, play video games, or spend hours on social media to take his mind off the situation. In a certain sense, emotion-focused coping can be thought of as treating the symptoms rather than the actual cause.

While many stressors elicit both kinds of coping strategies, problem-focused coping is more likely to occur when encountering stressors, we perceive as controllable, while emotion-focused coping is more likely to predominate when faced with stressors that we believe we are powerless to change (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). Clearly, emotion-focused coping is more effective in dealing with uncontrollable stressors. For example, the stress you experience when a loved one dies can be overwhelming. You are simply powerless to change the situation as there is nothing you can do to bring this person back. The most helpful coping response is emotion-focused coping aimed at minimizing the pain of the grieving period.

Fortunately, most stressors we encounter can be modified and are, to varying degrees, controllable. A person who cannot stand her job can quit and look for work elsewhere; a middle-aged divorcee can find another potential partner; the freshman who fails an exam can study harder next time, and a breast lump does not necessarily mean that one is fated to die of breast cancer.

Control and Stress

The desire and ability to predict events, make decisions, and affect outcomes—that is, to enact control in our lives—is a basic tenet of human behavior (Everly & Lating, 2002). Albert Bandura (1997) stated that “the intensity and chronicity of human stress is governed largely by perceived control over the demands of one’s life” (p. 262). As cogently described in his statement, our reaction to potential stressors depends to a large extent on how much control we feel we have over such things. Perceived control is our beliefs about our personal capacity to exert influence over and shape outcomes, and it has major implications for our health and happiness (Infurna & Gerstorf, 2014). Extensive research has demonstrated that perceptions of personal control are associated with a variety of favorable outcomes, such as better physical and mental health and greater psychological well-being (Diehl & Hay, 2010). Greater personal control is also associated with lower reactivity to stressors in daily life. For example, researchers in one investigation found that higher levels of perceived control at one point in time were later associated with lower emotional and physical reactivity to interpersonal stressors (Neupert, Almeida, & Charles, 2007). Further, a daily diary study with 34 older widows found that their stress and anxiety levels were significantly reduced on days during which the widows felt greater perceived control (Ong, Bergeman, & Bisconti, 2005).

People who report higher levels of perceived control view their health as controllable, thereby making it more likely that they will better manage their health and engage in behaviors conducive to good health (Bandura, 2004). Not surprisingly, greater perceived control has been linked to lower risk of physical health problems, including declines in physical functioning (Infurna, Gerstorf, Ram, Schupp, & Wagner, 2011), heart attacks (Rosengren et al., 2004), and both cardiovascular disease incidence (Stürmer, Hasselbach, & Amelang, 2006) and mortality from cardiac disease (Surtees et al., 2010). In addition, longitudinal studies of British civil servants have found that those in low-status jobs (e.g., clerical and office support staff) in which the degree of control over the job is minimal are considerably more likely to develop heart disease than those with high-status jobs or considerable control over their jobs (Marmot, Bosma, Hemingway, & Stansfeld, 1997).

The link between perceived control and health may provide an explanation for the frequently observed relationship between social class and health outcomes (Kraus, Piff, Mendoza-Denton, Rheinschmidt, & Keltner, 2012). In general, research has found that more affluent individuals experience better health partly because they tend to believe that they can personally control and manage their reactions to life’s stressors (Johnson & Krueger, 2006). Perhaps buoyed by the perceived level of control, individuals of higher social class may be prone to overestimating the degree of influence they have over particular outcomes. For example, those of higher social class tend to believe that their votes have greater sway on election outcomes than do those of lower social class, which may explain higher rates of voting in more affluent communities (Krosnick, 1990). Other research has found that a sense of perceived control can protect less affluent individuals from poorer health, depression, and reduced life-satisfaction—all of which tend to accompany lower social standing (Lachman & Weaver, 1998).

Taken together, findings from these and many other studies clearly suggest that perceptions of control and coping abilities are important in managing and coping with the stressors we encounter throughout life.

Social Support

The need to form and maintain strong, stable relationships with others is a powerful, pervasive, and fundamental human motive (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Building strong interpersonal relationships with others helps us establish a network of close, caring individuals who can provide social support in times of distress, sorrow, and fear. Social support can be thought of as the soothing impact of friends, family, and acquaintances (Baron & Kerr, 2003). Social support can take many forms, including advice, guidance, encouragement, acceptance, emotional comfort, and tangible assistance (such as financial help). Thus, other people can be very comforting to us when we are faced with a wide range of life stressors, and they can be extremely helpful in our efforts to manage these challenges. Even in nonhuman animals, species mates can offer social support during times of stress. For example, elephants seem to be able to sense when other elephants are stressed and will often comfort them with physical contact—such as a trunk touch—or an empathetic vocal response (Krumboltz, 2014).

Scientific interest in the importance of social support first emerged in the 1970s when health researchers developed an interest in the health consequences of being socially integrated (Stroebe & Stroebe, 1996). Interest was further fueled by longitudinal studies showing that social connectedness reduced mortality. In one classic study, nearly 7,000 Alameda County, California, residents were followed over 9 years. Those who had previously indicated that they lacked social and community ties were more likely to die during the follow-up period than those with more extensive social networks. Compared to those with the most social contacts, isolated men and women were, respectively, 2.3 and 2.8 times more likely to die. These trends persisted even after controlling for a variety of health-related variables, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, self-reported health at the beginning of the study, and physical activity (Berkman & Syme, 1979).

Since the time of that study, social support has emerged as one of the well-documented psychosocial factors affecting health outcomes (Uchino, 2009). A statistical review of 148 studies conducted between 1982 and 2007 involving over 300,000 participants concluded that individuals with stronger social relationships have a 50% greater likelihood of survival compared to those with weak or insufficient social relationships (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010). According to the researchers, the magnitude of the effect of social support observed in this study is comparable with quitting smoking and exceeded many well-known risk factors for mortality, such as obesity and physical inactivity (Figure 8.7).

A number of large-scale studies have found that individuals with low levels of social support are at greater risk of mortality, especially from cardiovascular disorders (Brummett et al., 2001). Further, higher levels of social supported have been linked to better survival rates following breast cancer (Falagas et al., 2007) and infectious diseases, especially HIV infection (Lee & Rotheram-Borus, 2001). In fact, a person with high levels of social support is less likely to contract a common cold. In one study, 334 participants completed questionnaires assessing their sociability; these individuals were subsequently exposed to a virus that causes a common cold and monitored for several weeks to see who became ill. Results showed that increased sociability was linearly associated with a decreased probability of developing a cold (Cohen, Doyle, Turner, Alper, & Skoner, 2003).

For many of us, friends are a vital source of social support. But what if you find yourself in a situation in which you have few friends and companions? Many students who leave home to attend and live at college experience drastic reductions in their social support, which makes them vulnerable to anxiety, depression, and loneliness. Social media can sometimes be useful in navigating these transitions (Raney & Troop Gordon, 2012) but might also cause increases in loneliness (Hunt, Marx, Lipson, & Young, 2018). For this reason, many colleges have designed first-year programs, such as peer mentoring (Raymond & Shepard, 2018), that can help students build new social networks. For some people, our families—especially our parents—are a major source of social support.

Social support appears to work by boosting the immune system, especially among people who are experiencing stress (Uchino, Vaughn, Carlisle, & Birmingham, 2012). In a pioneering study, spouses of cancer patients who reported high levels of social support showed indications of better immune functioning on two out of three immune functioning measures, compared to spouses who were below the median on reported social support (Baron, Cutrona, Hicklin, Russell, & Lubaroff, 1990). Studies of other populations have produced similar results, including those of spousal caregivers of dementia sufferers, medical students, elderly adults, and cancer patients (Cohen & Herbert, 1996; Kiecolt-Glaser, McGuire, Robles, & Glaser, 2002).

In addition, social support has been shown to reduce blood pressure for people performing stressful tasks, such as giving a speech or performing mental arithmetic (Lepore, 1998). In these kinds of studies, participants are usually asked to perform a stressful task either alone, with a stranger present (who may be either supportive or unsupportive), or with a friend present. Those tested with a friend present generally exhibit lower blood pressure than those tested alone or with a stranger (Fontana, Diegnan, Villeneuve, & Lepore, 1999). In one study, 112 female participants who performed stressful mental arithmetic exhibited lower blood pressure when they received support from a friend rather than a stranger, but only if the friend was a male (Phillips, Gallagher, & Carroll, 2009). Although these findings are somewhat difficult to interpret, the authors mention that it is possible that females feel less supported and more evaluated by other females, particularly females whose opinions they value.

Taken together, the findings above suggest one of the reasons social support is connected to favorable health outcomes is because it has several beneficial physiological effects in stressful situations. However, it is also important to consider the possibility that social support may lead to better health behaviors, such as a healthy diet, exercising, smoking cessation, and cooperation with medical regimens (Uchino, 2009).

Stress Reduction Techniques

Beyond having a sense of control and establishing social support networks, there are numerous other means by which we can manage stress (Figure 8.8). A common technique people use to combat stress is exercise (Salmon, 2001). It is well-established that exercise, both of long (aerobic) and short (anaerobic) duration, is beneficial for both physical and mental health (Everly & Lating, 2002). There is considerable evidence that physically fit individuals are more resistant to the adverse effects of stress and recover more quickly from stress than less physically fit individuals (Cotton, 1990). In a study of more than 500 Swiss police officers and emergency service personnel, increased physical fitness was associated with reduced stress, and regular exercise was reported to protect against stress-related health problems (Gerber, Kellman, Hartman, & Pühse, 2010).

One reason exercise may be beneficial is because it might buffer some of the deleterious physiological mechanisms of stress. One study found rats that exercised for six weeks showed a decrease in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responsiveness to mild stressors (Campeau et al., 2010). In high-stress humans, exercise has been shown to prevent telomere shortening, which may explain the common observation of a youthful appearance among those who exercise regularly (Puterman et al., 2010). Further, exercise in later adulthood appears to minimize the detrimental effects of stress on the hippocampus and memory (Head, Singh, & Bugg, 2012). Among cancer survivors, exercise has been shown to reduce anxiety (Speck, Courneya, Masse, Duval, & Schmitz, 2010) and depressive symptoms (Craft, VanIterson, Helenowski, Rademaker, & Courneya, 2012). Clearly, exercise is a highly effective tool for regulating stress.

In the 1970s, Herbert Benson, a cardiologist, developed a stress reduction method called the relaxation response technique (Greenberg, 2006). The relaxation response technique combines relaxation with transcendental meditation, and consists of four components (Stein, 2001):

- sitting upright on a comfortable chair with feet on the ground and body in a relaxed position,

- being in a quiet environment with eyes closed,

- repeating a word or a phrase—a mantra—to oneself, such as “alert mind, calm body,”

- passively allowing the mind to focus on pleasant thoughts, such as nature or the warmth of your blood nourishing your body.

The relaxation response approach is conceptualized as a general approach to stress reduction that reduces sympathetic arousal, and it has been used effectively to treat people with high blood pressure (Benson & Proctor, 1994) (Figure 8.9).

Another technique to combat stress, biofeedback, was developed by Gary Schwartz at Harvard University in the early 1970s. Biofeedback is a technique that uses electronic equipment to accurately measure a person’s neuromuscular and autonomic activity—feedback is provided in the form of visual or auditory signals (Figure 8.10). The main assumption of this approach is that providing somebody biofeedback will enable the individual to develop strategies that help gain some level of voluntary control over what are normally involuntary bodily processes (Schwartz & Schwartz, 1995). A number of different bodily measures have been used in biofeedback research, including facial muscle movement, brain activity, and skin temperature, and it has been applied successfully with individuals experiencing tension headaches, high blood pressure, asthma, and phobias (Stein, 2001).

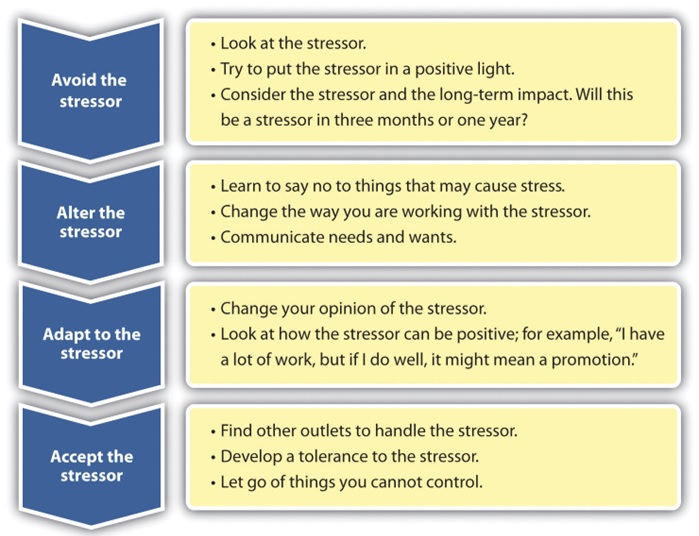

Understanding your current coping mechanisms for stress can help you determine what works to manage stress—and what doesn’t. Once we do some self-analysis, we can use a method called the four A’s (Sparks, 2019). The four A’s gives us four choices for dealing with a stressor (Figure 8.11):

- Avoid the stressor. We can try to avoid situations that stress us out. If watching certain television programs causes stress, stop watching them! Spend time with people who help you relax. We can also look at saying no more often if we do not have the time necessary to complete everything we are doing.

- Alter the stressor. Another option in dealing with stress is to try to alter it, if you can’t avoid it. This often involved problem-focused coping techniques. When changing a situation, you can be more assertive, manage time better, and communicate your own needs and wants better. For example, Karen can look at the things causing her stress, such as her home and school commitments; while she can’t change the workload, she can examine ways to avoid a heavy workload in the future. If Karen is stressed about the amount of homework she has and the fact that she needs to clean the house, asking for help from roommates, for example, can help alter the stressor. Often this involves the ability to communicate well.

- Adapt to the stressor. If you are unable to avoid or change the stressor, getting comfortable with the stressor is a way to handle it. Creating your own coping mechanisms for the stress and learning to handle it can be an effective way to handle the stress. These will likely employ emotion-focused coping techniques. For example, we can try looking at stressful situations in a positive light, consider how important the stressor is in the long run, and adjust our standards of perfectionism.

- Accept the stressor. Some stressors are unavoidable. We all have to go to work and manage our home life. So, learning to handle the things we cannot change by forgiving, developing tolerances, and letting going of those things we cannot control is also a way to deal with a stressor. This also involves emotion-focused coping. For example, if your mother-in-law’s yearly visits and criticisms cause stress, obviously you are not able to avoid or alter the stress, but you can adapt to it and accept it. Since we cannot control another person, accepting the stressor and finding ways of dealing with it can help minimize some negative effects of the stress we may experience.

Summary

- When faced with stress, people must attempt to manage or cope with it.

- In general, there are two basic forms of coping: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping.

- Those who use problem-focused coping strategies tend to cope better with stress because these strategies address the source of stress rather than the resulting symptoms.

- To a large extent, perceived control greatly impacts reaction to stressors and is associated with greater physical and mental well-being.

- Social support has been demonstrated to be a highly effective buffer against the adverse effects of stress.

- The four As of stress reduction can help us reduce stress. They include: avoid, alter, adapt, and accept. By using the four As to determine the best approach to deal with a certain stressor, we can begin to have a more positive outlook on the stressor and learn to handle it better.

Discussion Questions

- Although problem-focused coping seems to be a more effective strategy when dealing with stressors, do you think there are any kinds of stressful situations in which emotion-focused coping might be a better strategy?

- Describe how social support can affect health both directly and indirectly.

- Of the ways to handle stress listed in this chapter, which ones do you already integrate in your life? Do you engage in other methods not listed here? Share your ideas for stress reduction in small groups.

Remix/Revisions featured in this section

- Small editing revisions to tailor the content to the Psychology of Human Relations course and removal of some content.

- Remix of 4 Reducing Stress (Human Relations – Saylor) added to 14.4 Regulation of Stress (Psychology 2e – Openstax).

- Provided links to locations of images and CC licenses.

- Added doi links to references to comply with APA 7thedition formatting reference manual.

Attributions

CC Licensed Content, Original

Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Stevy Scarbrough. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Human Relations. Authored by: Saylor Academy. Provided by: Saylor Academy. Located at: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_human-relations/s07-04-reducing-stress.html License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Psychology 2e. Authored by: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett. Publisher: Openstax. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/14-4-regulation-of-stress License: CC-BY 4.0

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Bandura A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health education & behavior : the official publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 31(2), 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660

Baron, R. S., & Kerr, N. L. (2003). Group process, group decision, group action (2nd ed.). Open University Press.

Baron, R. S., Cutrona, C. E., Hicklin, D., Russell, D. W., & Lubaroff, D. M. (1990). Social support and immune function among spouses of cancer patients. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(2), 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.2.344

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Benson, H., & Proctor, W. (1994). Beyond the relaxation response: How to harness the healing power of your personal beliefs. Berkley Publishing Group.

Berkman, L. F., & Syme, S. L. (1979). Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American journal of epidemiology, 109(2), 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674

Brummett, B. H., Barefoot, J. C., Siegler, I. C., Clapp-Channing, N. E., Lytle, B. L., Bosworth, H. B., Williams, R. B., Jr, & Mark, D. B. (2001). Characteristics of socially isolated patients with coronary artery disease who are at elevated risk for mortality. Psychosomatic medicine, 63(2), 267–272. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200103000-00010

Campeau, S., Nyhuis, T. J., Sasse, S. K., Kryskow, E. M., Herlihy, L., Masini, C. V., Babb, J. A., Greenwood, B. N., Fleshner, M., & Day, H. E. (2010). Hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis responses to low-intensity stressors are reduced after voluntary wheel running in rats. Journal of neuroendocrinology, 22(8), 872–888. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02007.x

Cohen, S., Doyle, W. J., Turner, R., Alper, C. M., & Skoner, D. P. (2003). Sociability and susceptibility to the common cold. Psychological science, 14(5), 389–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.01452

Cohen, S., & Herbert, T. B. (1996). Health psychology: Psychological factors and physical disease from the perspective of human psychoneuroimmunology. Annual Review of Psychology, 47, 113–142. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.113

Cotton, D. H. G. (1990). Stress management: An integrated approach to therapy. Brunner/Mazel.

Craft, L. L., Vaniterson, E. H., Helenowski, I. B., Rademaker, A. W., & Courneya, K. S. (2012). Exercise effects on depressive symptoms in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 21(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0634

Diehl, M., & Hay, E. L. (2010). Risk and resilience factors in coping with daily stress in adulthood: the role of age, self-concept incoherence, and personal control. Developmental psychology, 46(5), 1132–1146. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019937

Everly, G. S., & Lating, J. M. (2002). A clinical guide to the treatment of the human stress response (2nd ed.). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishing.

Falagas, M. E., Zarkadoulia, E. A., Ioannidou, E. N., Peppas, G., Christodoulou, C., & Rafailidis, P. I. (2007). The effect of psychosocial factors on breast cancer outcome: a systematic review. Breast cancer research : BCR, 9(4), R44. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr1744

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 219–239. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136617

Fontana, A. M., Diegnan, T., Villeneuve, A., & Lepore, S. J. (1999). Nonevaluative social support reduces cardiovascular reactivity in young women during acutely stressful performance situations. Journal of behavioral medicine, 22(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018751702934

Gerber, M., Kellman, M., Hartman, T., & Pühse, U. (2010). Do exercise and fitness buffer against stress among Swiss police and emergency response service officers? Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11, 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.02.004

Greenberg, J. S. (2006). Comprehensive stress management (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Head, D., Singh, T., & Bugg, J. M. (2012). The moderating role of exercise on stress-related effects on the hippocampus and memory in later adulthood. Neuropsychology, 26(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027108

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS medicine, 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Hunt, M. G., Marx, R., Lipson, C., & Young, J. (2018). No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression. Journal and Social and Clinical Psychology, 37(10), 751–768. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2018.37.10.751

Infurna, F. J., & Gerstorf, D. (2014). Perceived control relates to better functional health and lower cardio-metabolic risk: The mediating role of physical activity. Health Psychology, 33(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030208

Infurna, F. J., Gerstorf, D., Ram, N., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2011). Long-term antecedents and outcomes of perceived control. Psychology and Aging, 26(3), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022890

Johnson, W., & Krueger, R. F. (2006). How money buys happiness: Genetic and environmental processes linking finances and life satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(4), 680–691. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.680

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., McGuire, L., Robles, T. F., & Glaser, R. (2002). Psychoneuroimmunology and psychosomatic medicine: Back to the future. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200201000-00004

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., Mendoza-Denton, R., Rheinschmidt, M. L., & Keltner, D. (2012). Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: How the rich are different from the poor. Psychological Review, 119(3), 546–572. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028756

Krosnick, J. A. (1990). Thinking about politics: Comparisons of experts and novices. Guilford.

Krumboltz, M. (2014, February 18). Just like us? Elephants comfort each other when they’re stressed out. Yahoo News. http://news.yahoo.com/elephants-know-a-thing-or-two-about-empathy-202224477.html

Lachman, M. E., & Weaver, S. L. (1998). The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 763–773. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.763

Lazarus, R. P., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

Lee, M., & Rotheram-Borus, M. J. (2001). Challenges associated with increased survival among parents living with HIV. American journal of public health, 91(8), 1303–1309. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.8.1303

Lepore, S. J. (1998). Problems and prospects for the social support-reactivity hypothesis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 20(4), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02886375

Marmot, M. G., Bosma, H., Hemingway, H., Brunner, E., & Stansfeld, S. (1997). Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. Lancet (London, England), 350(9073), 235–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04244-x

Neupert, S. D., Almeida, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (2007). Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: the role of personal control. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences, 62(4), P216–P225. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.4.p216

Ong, A. D., Bergeman, C. S., & Bisconti, T. L. (2005). Unique effects of daily perceived control on anxiety symptomatology during conjugal bereavement. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(5), 1057–1067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.07.004

Phillips, A. C., Gallagher, S., & Carroll, D. (2009). Social support, social intimacy, and cardiovascular reactions to acute psychological stress. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 37(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9077-0

Puterman, E., Lin, J., Blackburn, E., O’Donovan, A., Adler, N., & Epel, E. (2010). The power of exercise: Buffering the effect of chronic stress on telomere length. PLoS ONE, 5(5), Article e10837. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010837

Ranney, J. D., & Troop-Gordon, W. (2012). Computer-mediated communication with distant friends: Relations with adjustment during students’ first semester in college. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 848–861. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027698

Raymond, J. M., & Sheppard, K. (2018). Effects of peer mentoring on nursing students’ perceived stress, sense of belonging, self-efficacy and loneliness. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 8(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v8n1p16

Rosengren, A., Hawken, S., Ounpuu, S., Sliwa, K., Zubaid, M., Almahmeed, W. A., Blackett, K. N., Sitthi-amorn, C., Sato, H., Yusuf, S., & INTERHEART investigators (2004). Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11119 cases and 13648 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet (London, England), 364(9438), 953–962. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17019-0

Salmon, P. (2001). Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: A unifying theory. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(1), 33–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00032-X

Schwartz, N. M., & Schwartz, M. S. (1995). Definitions of biofeedback and applied physiology. In M. S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.), Biofeedback: A practitioner’s guide (pp. 32–42). Guilford.

Sparks, D. (2019, April 24). Mayo mindfulness: Try the 4 A’s for stress relief. Mayo Clinic News Network. Retrieved October 23, 2022 from https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/mayo-mindfulness-try-the-4-as-for-stress-relief/

Speck, R. M., Courneya, K. S., Mâsse, L. C., Duval, S., & Schmitz, K. H. (2010). An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice, 4(2), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5

Stein F. (2001). Occupational stress, relaxation therapies, exercise and biofeedback. Work (Reading, Mass.), 17(3), 235–245.

Stroebe, W., & Stroebe, M. (1996). The social psychology of social support. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 597–621). Guilford.

Stürmer, T., Hasselbach, P., & Amelang, M. (2006). Personality, lifestyle, and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer: follow-up of population-based cohort. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 332(7554), 1359. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38833.479560.80

Surtees, P. G., Wainwright, N. W. J., Luben, R., Wareham, N. J., Bingham, S. A., & Khaw, K.-T. (2010). Mastery is associated with cardiovascular disease mortality in men and women at apparently low risk. Health Psychology, 29(4), 412–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019432

Uchino B. N. (2009). Understanding the Links Between Social Support and Physical Health: A Life-Span Perspective With Emphasis on the Separability of Perceived and Received Support. Perspectives on psychological science : a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 4(3), 236–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x

Uchino, B. N., Vaughn, A. A., Carlisle, M., & Birmingham, W. (2012). Social support and immunity. In S. C. Segerstrom (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of psychoneuroimmunology (pp. 214–233). Oxford University Press.