9.1 Understanding Conflict

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the key elements of conflict.

- Explain different levels at which conflict can occur.

- Summarize stages in the conflict process.

- Recognize characteristics of conflict escalation.

Who do you have the most conflict with right now? Your answer to this question probably depends on the various contexts in your life. If you still live at home with a parent or parents, you may have daily conflicts with your family as you try to balance your autonomy, or desire for independence, with the practicalities of living under your family’s roof. If you’ve recently moved away to go to college, you may be negotiating roommate conflicts as you adjust to living with someone you may not know at all. You probably also have experiences managing conflict in romantic relationships, friendships, and in the workplace. In this module, we will introduce some introductory concepts and explore why understanding conflict is important for your career success and interpersonal relationships.

There are many different definitions of conflict existing in the literature. For our purposes, conflict occurs in interactions in which there are real or perceived incompatible goals, scarce resources, or opposing viewpoints. Conflict can vary in severity from mild to grievous and can be expressed verbally or nonverbally along a continuum ranging from a nearly imperceptible cold shoulder to a very obvious blowout.

Elements of Conflict

There are six elements to a conflict described by Rice (2000):

- Conflict is inevitable. Because we do not all think and act the same, disagreements will occur.

- Conflict by itself is neither good nor bad. Leaving conflict unresolved can result in negative outcomes. It is important to work toward resolving conflict and achieving a positive outcome.

- Conflict is a process. We choose how to respond to others and can escalate or deescalate a conflict.

- Conflict and avoid conflict both consume energy. The longer we avoid working on a resolution for a conflict with someone else, the more energy we spend on it.

- Conflict has elements of both content and feeling. While conflict often arises from a specific behavior or action, it often involves underlying emotions. For example, if your significant other always left dirty dishes in the sink, despite your requests to rinse and put them in the dishwasher, you may feel like your partner doesn’t respect you. This may lead to a conflict over doing the dishes.

- We can choose to be proactive or reactive in a conflict. Taking a proactive approach to resolving conflict when it arises can lead to more positive outcomes.

Other Key Terms

Some people use the terms conflict, competition, dispute, and violence interchangeably. While these concepts are similar, they aren’t exactly the same. We will define each of these terms to ensure that we have a shared understanding of how they are used.

Dispute is a term for a disagreement between parties. Typically, a dispute is adversarial in nature. While conflict can be hostile, it isn’t always . Dispute also sometimes carries with it a legal connotation.

Competition is a rivalry between two groups or two individuals over an outcome that they both seek. In a competition there is a winner and a loser. Parties involved in a conflict may or may not view the situation as a competition for resources. Ideally, parties in a conflict will work together rather than compete.

The term interpersonal violence is also not synonymous with conflict. Although some conflict situations escalate to include acts of aggression and hostility, interpersonal violence involves acts of aggression such as an intent to harm or actual physical or psychological harm to another or their property. Ideally, conflict will be productive, respectful, and non-violent.

Levels of Conflict

In addition to different views of conflict, there exist several different levels of conflict. By level of conflict, we are referring to the number of individuals involved in the conflict. That is, is the conflict within just one person, between two people, between two or more groups, or between two or more organizations? Both the causes of a conflict and the most effective means to resolve it can be affected by level. Four levels can be identified: within an individual (intrapersonal conflict), between two parties (interpersonal conflict), between groups (intergroup conflict), and between organizations (inter-organizational conflict) (Figure 9.1).

Intrapersonal Conflict

Intrapersonal conflict arises within a person. In the workplace, this is often the result of competing motivations or roles. We often hear about someone who has an approach-avoidance conflict; that is, they are both attracted to and repelled by the same object. Similarly, a person can be attracted to two equally appealing alternatives, such as two good job offers (approach-approach conflict) or repelled by two equally unpleasant alternatives, such as the threat of being fired if one fails to identify a coworker guilty of breaking company rules (avoidance-avoidance conflict). Intrapersonal conflict can arise because of differences in roles.

A role conflict occurs when there are competing demands on our time, energy, and other resources. For example, a conflict may arise if you’re the head of one team but also a member of another team. We can also have conflict between our roles at work and those roles that we hold in our personal lives.

Another type of intrapersonal conflict involves role ambiguity. Perhaps you’ve been given the task of finding a trainer for a company’s business writing training program. You may feel unsure about what kind of person to hire—a well-known but expensive trainer or a local, unknown but low-priced trainer. If you haven’t been given guidelines about what’s expected, you may be wrestling with several options.

Interpersonal Conflict

Interpersonal conflict is among individuals such as coworkers, a manager and an employee, or CEOs and their staff. Many companies suffer because of interpersonal conflicts as it results in loss of productivity and employee turnover. According to one estimate, 31.9% of CEOs resigned from their jobs because they had conflict with the board of directors (Whitehouse, 2008). Such conflicts often tend to get highly personal because only two parties are involved and each person embodies the opposing position in the conflict. Hence, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between the opponent’s position and the person. Keeping conflicts centered around ideas rather than individual differences is important in avoiding a conflict escalation.

Intergroup Conflict

Intergroup conflict is conflict that takes place among different groups and often involves disagreement over goals, values, or resources. Types of groups may include different departments, employee unions, or management in a company or competing companies that supply the same customers. Departments may conflict over budget allocations, unions and management may disagree over work rules, and suppliers may conflict with each other on the quality of parts.

Merging two groups together can lead to friction between the groups—especially if there are scarce resources to be divided among the group. For example, in what has been called “the most difficult and hard-fought labor issue in an airline merger,” Canadian Air and Air Canada pilots were locked into years of personal and legal conflict when the two airlines’ seniority lists were combined following the merger (Stoykewch, 2003). Seniority is a valuable and scarce resource for pilots, because it helps to determine who flies the newest and biggest planes, who receives the best flight routes, and who is paid the most. In response to the loss of seniority, former Canadian Air pilots picketed at shareholder meetings, threatened to call in sick, and had ongoing conflicts with pilots from Air Canada. The history of past conflicts among organizations and employees makes new deals challenging. As the Canadian airline WestJet is now poised to takeover Sunwing, WestJet has stated that they will respect existing union agreements (Mallees, 2022). Intergroup conflict can be the most complicated form of conflict because of the number of individuals involved. Coalitions can form and result in an “us-against-them” mentality. Here, too, is an opportunity for groups to form insulated ways of thinking and problems solving, thus allowing groupthink to develop and thrive.

Interorganizational Conflict

Finally, we can see interorganizational conflict in disputes between two companies in the same industry (for example, a disagreement between computer manufactures over computer standards), between two companies in different industries or economic sectors (for example, a conflict between real estate interests and environmentalists over land use planning), and even between two or more countries (for example, a trade dispute between the United States and Russia). In each case, both parties inevitably feel the pursuit of their goals is being frustrated by the other party.

Types of Conflict

If we are to try to understand conflict, we need to know what type of conflict is present. At least four types of conflict can be identified:

- Goal conflict can occur when one person or group desires a different outcome than others do. This is simply a clash over whose goals are going to be pursued.

- Cognitive conflict can result when one person or group holds ideas or opinions that are inconsistent with those of others. Often cognitive conflicts are rooted in differences in attitudes, beliefs, values, and worldviews, and ideas may be tied to deeply held culture, politics, and religion. This type of conflict emerges when one person’s or group’s feelings or emotions (attitudes) are incompatible with those of others.

- Affective conflict is seen in situations where two individuals simply don’t get along with each other.

- Behavioral conflict exists when one person or group does something (i.e., behaves in a certain way) that is unacceptable to others. Dressing for work in a way that “offends” others and using profane language are examples of behavioral conflict.

Each of these types of conflict is usually triggered by different factors, and each can lead to very different responses by the individual or group. It is important to note that there are many types of conflict and that not all researchers use this same four-type classification. For example, Gallo (2015) has characterized conflict as being rooted in relationships, tasks (what to do), process (how to do things), or status. Regardless, when we find ourselves in a conflict situation, it can be helpful to try and take a step back and identify what type of conflict it is. It can also be helpful to acknowledge that what may look like a goal conflict may actually also have components of affective or cognitive conflict.

The Conflict Process

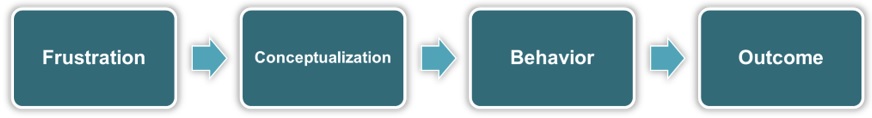

The most commonly accepted model of the conflict process consists of four stages: (1) frustration, (2) conceptualization, (3) behavior, and (4) outcome (Thomas, 1976)(Figure 9.2).

Stage 1: Frustration

As we have seen, conflict situations originate when an individual or group feels frustration in the pursuit of important goals. This frustration may be caused by a wide variety of factors, including disagreement over performance goals, failure to get a promotion or pay raise, a fight over scarce economic resources, new rules or policies, and so forth. In fact, conflict can be traced to frustration over almost anything a group or individual cares about.

Stage 2: Conceptualization

In stage 2, the conceptualization stage of the model, parties to the conflict attempt to understand the nature of the problem, what they themselves want as a resolution, what they think their opponents want as a resolution, and various strategies they feel each side may employ in resolving the conflict. This stage is really the problem-solving and strategy phase. For instance, when management and union negotiate a labor contract, both sides attempt to decide what is most important and what can be bargained away in exchange for these priority needs.

Stage 3: Behavior

The third stage in Thomas’s model is actual behavior. As a result of the conceptualization process, parties to a conflict attempt to implement their resolution mode by competing or accommodating in the hope of resolving problems. A major task here is determining how best to proceed strategically. That is, what tactics will the party use to attempt to resolve the conflict? Thomas has identified five modes for conflict resolution: (1) competing, (2) collaborating, (3) compromising, (4) avoiding, and (5) accommodating. We will discuss these modes in further detail in the next section.

Stage 4: Outcome

Finally, as a result of efforts to resolve the conflict, both sides determine the extent to which a satisfactory resolution or outcome has been achieved. Where one party to the conflict does not feel satisfied or feels only partially satisfied, the seeds of discontent are sown for a later conflict. One unresolved conflict episode can easily set the stage for a second episode. Managerial action aimed at achieving quick and satisfactory resolution is vital; failure to initiate such action leaves the possibility (more accurately, the probability) that new conflicts will soon emerge.

Conflict Escalation

Many academics and conflict resolution practitioners have observed predictable patterns in the way conflict escalates. Conflict is often discussed as though it is a separate entity, and in fact it is true that an escalating dispute may seem to take on a life of its own. Conflict will often escalate beyond reason unless a conscious effort is made to end it.

Figure 9.3 is called the conflict escalation tornado. It demonstrates how conflict can quickly escalate out of control. By observing and listening to individuals in dispute, it is often possible to determine where they are in the escalation process and anticipate what might occur next. In doing so, one can develop timely and appropriate approaches to halt the process.

Culture and Conflict

Culture is an important context to consider when studying conflict. While there are some generalizations we can make about culture and conflict, it is better to look at more specific patterns of how interpersonal communication and conflict management are related. We can better understand some of the cultural differences in conflict management by further examining the concept of face.

What does it mean to “save face?” This saying generally refers to preventing embarrassment or preserving our reputation or image, which is similar to the concept of face in interpersonal and intercultural communication. Our face is the projected self we desire to put into the world, and facework refers to the communicative strategies we employ to project, maintain, or repair our face or maintain, repair, or challenge another’s face. Face negotiation theory argues that people in all cultures negotiate face through communication encounters, and that cultural factors influence how we engage in facework, especially in conflict situations (Oetzel & Ting-Toomey, 2003). These cultural factors influence whether we are more concerned with self-face or other-face and what types of conflict management strategies we may use. One key cultural influence on face negotiation is the distinction between individualistic and collectivistic cultures.

The distinction between individualistic and collectivistic cultures is an important dimension across which all cultures vary. Individualistic cultures like the United States and most of Europe emphasize individual identity over group identity and encourage competition and self-reliance. Collectivistic cultures like Taiwan, Colombia, China, Japan, Vietnam, and Peru value in-group identity over individual identity and value conformity to social norms of the in-group (Dsilva & Whyte, 1998). However, within the larger cultures, individuals will vary in the degree to which they view themselves as part of a group or as a separate individual, which is called self-construal. Independent self-construal indicates a perception of the self as an individual with unique feelings, thoughts, and motivations. Interdependent self-construal indicates a perception of the self as interrelated with others (Oetzel & Ting-Toomey, 2003). Not surprisingly, people from individualistic cultures are more likely to have higher levels of independent self-construal, and people from collectivistic cultures are more likely to have higher levels of interdependent self-construal. Self-construal and individualistic or collectivistic cultural orientations affect how people engage in facework and the conflict management styles they employ.

Self-construal alone does not have a direct effect on conflict style, but it does affect face concerns, with independent self-construal favoring self-face concerns and interdependent self-construal favoring other-face concerns. There are specific facework strategies for different conflict management styles, and these strategies correspond to self-face concerns or other-face concerns.

- Accommodating. Giving in (self-face concern).

- Avoiding. Pretending conflict does not exist (other-face concern).

- Competing. Defending your position, persuading (self-face concern).

- Collaborating. Apologizing, having a private discussion, remaining calm (other-face concern) (Oetzel, Garcia, & Ting-Toomey, 2008).

Research done on college students in Germany, Japan, China, and the United States found that those with independent self-construal were more likely to engage in competing, and those with interdependent self-construal were more likely to engage in avoiding or collaborating (Oetzel & Ting-Toomey, 2003). And in general, this research found that members of collectivistic cultures were more likely to use the avoiding style of conflict management and less likely to use the integrating or competing styles of conflict management than were members of individualistic cultures. The following examples bring together facework strategies, cultural orientations, and conflict management style: Someone from an individualistic culture may be more likely to engage in competing as a conflict management strategy if they are directly confronted, which may be an attempt to defend their reputation (self-face concern). Someone in a collectivistic culture may be more likely to engage in avoiding or accommodating in order not to embarrass or anger the person confronting them (other-face concern) or out of concern that their reaction could reflect negatively on their family or cultural group (other-face concern). While these distinctions are useful for categorizing large-scale cultural patterns, it is important not to essentialize or arbitrarily group countries together, because there are measurable differences within cultures. For example, expressing one’s emotions was seen as demonstrating a low concern for other-face in Japan, but this was not so in China, which shows there is variety between similarly collectivistic cultures. Culture always adds layers of complexity to any communication phenomenon, but experiencing and learning from other cultures also enriches our lives and makes us more competent communicators.

Summary

- Conflict occurs in interaction in which there are real or perceived incompatible goals, scarce resources, or opposing viewpoints.

- Conflict will inevitably occur and isn’t inherently good or bad.

- Conflict can occur at different levels: within individuals, between individuals, between groups, and between organizations.

- The four types of conflict are: goal conflict, cognitive conflict, affective conflict, and behavioral conflict.

- The conflict process consists of four stages: frustration, conceptualization, behaviour, and outcomes.

- Culture influences how we engage in conflict based on our cultural norms regarding individualism or collectivism and concern for self-face or other-face.

Discussion Questions

- Think of your most recent communication with another individual. Write down this conversation and, within the conversation, identify the components of the communication process.

- Think about the different types of noise that affect communication. Can you list some examples of how noise can make communication worse?

- We all do something well in relation to communication. What are your best communication skills? In what areas would you like to improve?

Remix/Revisions featured in this section

- Small editing revisions to tailor the content to the Psychology of Human Relations course.

- Remix of combining sections of Introduction to Conflict and Conflict Resolution, Negotiations, and Labour Relations (Conflict Management – Open Library) and adding 2 Conflict and Interpersonal Communication (Communication in the Real World – University of Minnesota Libraries).

- Changed formatting for images to provide links to locations of images and CC licenses.

- Added doi links to references to comply with APA 7th edition formatting reference manual.

Attributions

CC Licensed Content, Original

Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Stevy Scarbrough. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Communication in the Real World. Authored by: University of Minnesota. Located at: https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/chapter/6-2-conflict-and-interpersonal-communication/ License: CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

CC Licensed Content Shared Previously

Conflict Management Authored by: Laura Westmaas. Published by: Open Library Located at: https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/conflictmanagement/ License: CC BY 4.0

References

Dsilva, M. U., & Whyte, L. O. (2010). Cultural differences in conflict styles: Vietnamese refugees and established residents. Howard Journal of Communication 9(1), 57-68. https://doi.org/10.1080/106461798247113

Gallo, A. (2015, November 4). 4 types of conflict and how to manage them [Podcast]. In Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/podcast/2015/11/4-types-of-conflict-and-how-to-manage-them

Mallees, N. A. (2022, March 2). WestJet Airlines to acquire Sunwing: Competition Bureau says it will review proposed transaction. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/westjet-sunwing-acquisition-1.6370021

Oetzel, J., Garcia, A. J. and Ting‐Toomey, S. (2008). An analysis of the relationships among face concerns and facework behaviors in perceived conflict situations: A four‐culture investigation. International Journal of Conflict Management, 19(4), 382-403. https://doi.org/10.1108/10444060810909310

Oetzel, J. G., & Ting-Toomey, S. (2003). Face concerns in interpersonal conflict: A cross- cultural empirical test of the face negotiation theory. Communication Research, 30(6), 599-624. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650203257841

Rice, S. (2000). Non-violent conflict management: Conflict resolution, dealing with anger, and negotiation and mediation. Berkeley: University of California at Berkeley, California Social Work Education Center. https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/21446/overview-old

Stoykewych, R. E. (2003, March 7). A note on the seniority resolutions arising out of the merger of Air Canada and Canadian Airlines [Paper presentation]. American Bar Association Midwinter Meeting, Laguna Beach, CA.

Thomas, K. (1976). Conflict and conflict management. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 889-935). Rand McNally.

Whitehouse, K. (2008, January 14). Why CEOs need to be honest with their boards. Wall Street Journal (Eastern edition), R1–R3. Retrieved November 19, 2022 from https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB119997940802681015