9 Light Art, Installation, and Land Art

Light Art, Installation, and Land Art

Elements of New Media Art in Light Art

As you explore Light Art in the first part of this chapter notice when you recognize these elements of New Media Art:

- Expands the definition of art

- Exploits new technology for artistic purposes

- Readymade – uses objects or material from everyday life

- Remixing – uses images or things made by others in new ways

- Merges new media with old media

- Ephemeral – isn’t meant to or can’t last forever

Perspective is Everything

Although pioneered in many ways by Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), a leading figure in the Dada movement, many artists in the late 1950s and early 1960s were beginning to conceive art-making as a process that requires the viewer for completion. A rethinking of the relationship between the artists, the artwork, and the viewer prompted new approaches to existing fine art forms, such as painting and sculpture, and encouraged artist exploration of potential in newer art, such as performances, happenings, video art, installations, earth art, and installations. Many of these forms not only invited, but sometimes even required audience participation. (See a further discussion of the influence of Dada on New Media Art in the Introduction to this book.)

Revolving the artwork around the spectator, hinges on their experience and their perception. In this pursuit, artists were drawn to expanding beyond three-dimensions, beyond depth, instead relying also upon time, motion, and other senses. Land art, installation art, and light art, are centered around the perception of the spectator.

Most Minimalist and Conceptual artists were—in part thanks to prominent artists like Duchamp and Robert Morris (1931-2018)—more aware of the role of the viewer, increasingly conceiving of artworks that communicate experiences instead of narrative or messages. For media such as painting and sculpture, this initially entailed focusing on specific visual elements and select principles of design to engage the spectator.

The scale of Mark Rothko’s (1903-1970) colorfield paintings combined with the nuanced emphasis of color, for example, immerses the spectator and creates an experience disjointed from the conventional visual consumption. When the focus is shifted to the perspective of the spectator, the limitations of two-dimensional media become very apparent and, thus, the shift to new media became more attractive to artists engaging in this discourse.

Watch & Consider: Art and Science

Expanding art into other dimensions took a scientific probing that enveloped artistic careers and spanned decades. Indeed, the explorations of new media and of perception paralleled scientific development since the beginning of the Modern era. Science and science fiction inspired many authors to push against limits of understanding and re-imagine the world as it is and as it could be. Microscopes revealed hidden life and worlds, telescopes confirmed the Earth itself infinitesimal in the cosmos, physicists recognized relativity, locomotion changed forever, humanity stood with its ships at the shores of a new world ocean, so-to-speak.

In his television miniseries, Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, renown scientist Carl Sagan (1934-1996) explained how difficult it can be to think out-of-the-box when it comes to perceiving dimensions, a concept creatively and famously employed in the science fiction book Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions (1882). Shifting paradigms in any field is often a slow and difficult process. While media and technological development in art is focus of this text, it is important to periodically take a step back and consider the interdisciplinary relationships. The avenues pursued by artists, might seem logical now, but until its done for the first time each step is a step into the dark. Thus, artistic practice in many of these fields are model after the scientific method. Each idea is postulated, systematically tested; results are peer reviewed; approaches change after each experiment.

Light Art

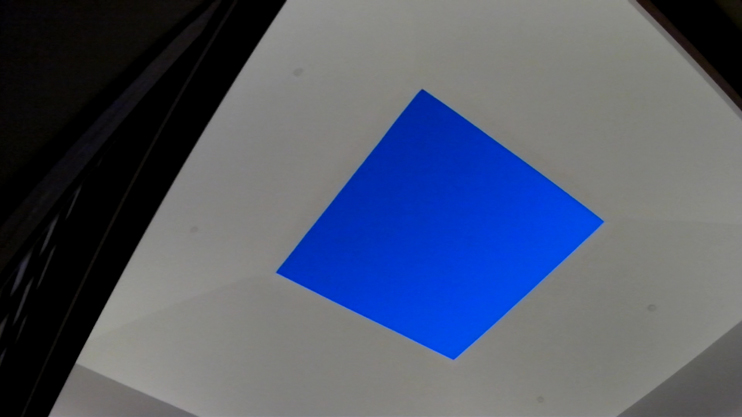

Consider contemporary light artist James Turrell’s (born 1943) fields of color, using colored light, such as Image 4. Milk Run II (1997) or Outside In (2021). Because these fields of color are created by opening in the gallery wall backed with a brightly illuminated plane, it can be difficult to discern its exact location. The mechanics of the projection manipulate the eye in a way that a fixed, two-dimensional object cannot, making it seem more like a mystical apparition. As noted in previous chapters, the artistic implementation of technology can not only serve aestheticism, but also can enhance experience for the spectator.

In New York, American Artist Dan Flavin (1933-1996) gained notoriety for creating sculptural objects and installations from commercially available fluorescent lighting fixtures. Flavin’s initial designs were drawings and paintings, reflective of Abstract Expressionist influence. In 1959, he began to make physical assemblages, mixed media sculpture, and collages that included found objects from the urban environments. In Southern California around this time, a loosely affiliated collective of about twenty artists interested in light art and new dimensions emerged, the art movement known as Light and Space. Installations associated with this movement focused on perceptual phenomena, such as light, volume and scale, and the use of materials such as glass, neon, fluorescent lights, resin and cast acrylic. Light and Space artists emphasized the experience of the spectator’s experience often by directing the sources of natural light and artificial light within objects or architecture. In other cases, artists manipulated light, using transparent, opaque or reflective materials.

In 1963, the first of Flavin’s more mature works began to be exhibited, works that exclusively utilized commercial, fluorescent lighting. In the decades that followed, he continued to use fluorescent structures to explore color, light and sculptural space, in works that filled gallery interiors. While most of Flavin’s installations were untitled, titles were commonly supplemented with a dedication to friends, contemporary artists, and other significant individuals in parenthesis. Monuments to V. Tatlin, for example, served as a homage to the Russian Constructivist sculptor Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953). By 1968, Flavin had developed his light sculptures into complete installations. Flavin continued these pyramidal light sculptures and installations as an ongoing series until 1990.

Parallel to the Light and Space collective in Los Angeles, artist James Turrell began experimenting with light in his studio in Santa Monica in the mid-sixties. By strategically covering the windows and only allowing specific exterior light to permeate the interior, Turrell began creating light projections. Furthering the idea, Turrell explored the phenomenon of sensory deprivation together with Los Angeles artist Robert Irwin.

Their collaborations went on to influence an art-and-technology program initiated by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1967 and were reflected in the 1971 exhibition at UCLA “Transparency, Reflection, Light, Space: Four Artists”.

These early explorations in light art evolved into career long trajectories for many artists. In 1971 Flavin drafted a concept for a site-specific installation that wasn’t fully realized until 1991, when the installation filled the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s entire rotunda celebrating the museum’s reopening. The sculptural, minimalist interior space of the Guggenheim Museum can be appreciated in its own right, however the space has always lent itself well to installation pieces, an interesting challenge for Light and Space artists.

In 2013 Turrell presented the new project, Aten Reign (2013), in the Guggenheim rotunda, filling the immense space with shifting artificial and natural light. The exhibition effectively served as a tour d’horizon of the artist’s explorations of perception, light, color, and space.

Read & Consider: Light and Perception

The phenomenon of light in the visual arts is a significant journey through time and art history. From animation of Paleolithic cave paintings to illumination of Carravagio’s (1571-1650) oil paintings or Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s (1598-1680) divine statues in the Italian Baroque, from Claude Monet’s (1840-1926) Modernist studies of atmospheric light to Daguerre’s capture of light on silver plates, from Flavin’s Postmodernist sculptures of light to the contemporary exhibitions of fireworks by Cai Guo-Qiang (born 1957). The relevance of light and perception became a greater focal point in aesthetic and phenomenological philosophy in the mid-twentieth century.

French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) published the text “Phenomenology of Perception” in 1945 and garnered enough interest in the 1960s to warrant an English translation and global publication. Prominent American artists, art theorists, and writers continued the discourse, as seen in the works and writings of Donald Judd (1928-1994) and Robert Morris. These minds that helped architect Minimalist and Conceptual art, made equally significant contributions to the development of performance art, land art, light art, and installation art. Many of Morris’ writings in the 1960s aimed to demonstrate the significance and subjective nature of the spectator’s experience. “Even the most unalterable property, shape does not remain constant. For with each shift in position the viewer also constantly changes the apparent shape of the work.” The Conceptual understanding of art maintains that the raison d’être of an artwork hinges entirely on its viewer. Morris noted in 1975, “Our encounter with objects in space forces us to reflect on ourselves, which can never become the objects for our external examination. In the domain of real space the subject-object dilemma can never be resolved.” The consideration of the site, viewer engages with and experiences the artwork, therefore is equally as integral as the object itself. In this context, land art, installation art, and light art can be much better understood.

Contemporary Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang used the phenomenological approach of light art and site-specific installations to relay not just an experience, but partake in the discourse of contemporary political and cultural issues. Much of his oeuvre has been explosive gunpowder drawings and ephemeral sculptures, but his City of Flowers in the Sky (2018) is worth noting here for its use of light and site-specific nature. To celebrate the city of Florence as the epicenter of the Italian Renaissance, Guo-Qiang created a colorful semblance of flowers using fireworks across a background of blue sky. The ephemeral piece lasted roughly ten minutes on Piazzale Michelangelo overlooking the city. Inspired by Sandro Botticelli’s (c.1445-1510) Renaissance masterpiece Primavera, some 50,000 fireworks released colorful smoke that resembled thousands of flowers.

Installation Art

Elements of New Media Art in Installation Art

As you explore Installation Art in the second part of this chapter notice when you recognize the following elements of New Media Art:

- Expands the definition of art

- Remixing – uses images or things made by others in new ways

- Merges new media with old media

- Ephemeral – isn’t meant to or can’t last forever

- Liveness – happens in real time, the artist is there

- Collaborative – the artist is a facilitator and viewers make the art with them

Installation artworks are designed to occupy an entire room or interior space that the spectator navigates in order to fully experience the work of art. Some installations are designed simply to be walked around (in-the-round) and contemplated or just from a specific vantage point. One characteristic of installation art that separates it from sculpture or other traditional two-dimensional artforms is its expansion into space and guided sensory command of the view’s interaction. The dimensional design creates a unified experience, rather than a display of separate, individual artworks.

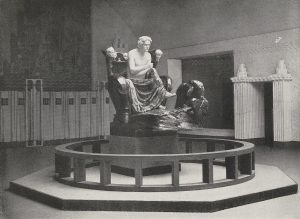

During the turn of the twentieth century such exhibitions were commonplace in movements like those of the Wiener Secession or the Arts and Crafts movement, where exhibition spaces were designed to display works coordinated by artists that shared formal and conceptual unity. The innovative composition of artists and artworks became known as the Gesamtkunstwerk (“Total Work of Art”), as embodied in the 1902 Beethoven exhibition in Vienna with a sculpture of Beethoven by Max Klinger (1857-1920). In the Postmodernist era, Conceptual and Minimalist arts revisited the spatial emphasis of the Gesamtkunstwerk, while narrowing the scope of the vision to that of a single artist and more often a single visual element. Russian artist Ilya Kabakov (born 1933) once noted that “The main actor in the total installation, the main centre toward which everything is addressed, for which everything is intended, is the viewer.”

Much of the postwar installation art movement emerged out of environments created by artists like American artist Allan Kaprow (1927-2006), who helped pioneer the “environment” and “happening” in the late 1950s and 1960s. Kaprow said of his first environment 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (1959), “I just simply filled the whole gallery up […] When you opened the door you found yourself in the midst of an entire environment.” For this exhibition, Kaprow divided the inside of a gallery into three smaller spaces using wooden frames stretched with translucent plastic sheets. Each room was illuminated with different colors and in each room the audience was forced to sit and observe the performances. (See the chapter on Social Practice Art for a further discussion of Kaprow and his influence on New Media Art.)

As noted in earlier chapters, the 1960s marked a significant time for emerging artistic formats as artists pivoted away from historical fine art media, such as drawing, painting, and sculpture. Liberation in media allowed artists to first focus on an underlying concept that they wished to communicate and then explore a range of media until they found an appropriate platform for development. Art critics John R. Chandler and Lucy Lippard described this shift as “the dematerialization of art.” One of the natural directions for artistic expression in the wake of dematerialization was the communication of ephemeral experiences. The dimensions of installations and site-specific works lend themselves in particular to this end.

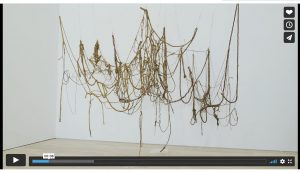

American Artist Eva Hesse (1936-1970) was interested both in using industrial media Minimalist sculpture and the formal, abstractionist vocabulary, used by artists like Robert Morris and Donald Judd. Morris published several writings outlining the Minimalist approach to process and materials in “Notes on Sculpture” and “Anti-Form”. However, Hesse parted from her male contemporaries in media, producing her own unique style within the movement. Instead of using smooth, flat industrial materials that produce sterile. machine-like surfaces, Hesse opted for materials like fiberglass, latex, and resins that produced textures and a translucency that felt more organic.

No Title (1969-70) exemplifies this practice, a work that is composed of knotted ropes, dipped in liquid latex, and hung from the ceiling to dry. The organic entanglement of loops and runs mimic the forms of internal organs and in many ways are as expressive as Jackson Pollock’s (1912-1956) action-painted drips. This irregular, emotive style was a far cry from the clean-cut forms of her contemporaries. Lippard, known for feminist critique at this time, praised Hesse’s abstracted style as a welcomed alternative to the male-dominated Minimalism.

In 1979 the installation The Dinner Party organized by Judy Chicago (born 1939) continued the subversion of museum space and institutional history. During the 1960s the calls from activists regarding the discrimination of women gained intensity and as an expression of this growing movement, women artists like Chicago drew attention to feminist discourse, such as minority of women artists represented in art institutions, how women are represented as subjects, and how artistic media ascribed to women has historically been excluded from the realm of fine art. The collaborative work The Dinner Party was the accomplishment of many women artists under the direction of Chicago, a reaction to the aforementioned discourse as well as a criticism of the individualistic nature of art production.

The resulting work itself was a large triangular table. The form is conceived as an equilateral triangle to symbolize femininity and the equality that feminism aims to achieve. Each side features 13 place settings: 13 being the number of men at the Christian Last Supper and the number of witches in a coven. These 39 settings are dedicated to diverse, historically significant women, from the Ancient Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut (died 1458 BCE) to Italian noblewoman Isabella d’Este (1474-1539) to American painter Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986). Each oversized place setting was adorned with an embroidered fabric table runner and 14-inch porcelain plate decorated to honor the individual. While some plates were ornamented with two-dimensional designs, others were made in high relief, representing sexualized flower motifs and female genitalia. On a whole, the installation celebrates marginalized historical women and historically marginalized artforms like needlework and ceramic painting.

A similar conceptual approach was exercised by Jenny Holzer (born 1950) with the exhibition of her Truisms (1977-87) in diverse forms and spaces. The Truisms were a series of short, witty maxims intending to get the spectator to think or consider a position by communicating an aggressive, humorous, or aggressive statement, such as “Abuse of power comes as no surprise” or “Bad intentions can yield good results”. These messages were displayed unsuspectingly on flyers, clothing, telephone booths, building walls, and even as an electronic installation in Times Square in New York City.

In the late 1980s and the early 1990s volatility in the art market spurred a reawakened of interest in conceptual art (art focused on ideas rather than objects) and the dematerialization of art that led installation art to rely stronger on light and sound. Many contemporary artists began reexamining the practices established by previous artistic styles and movements. The installation works of American artist Tara Donovan (born 1969), for example, resemble those of Minimalism. Her installation Untitled (2003) fills an entire room of the Ace Gallery in Los Angeles. As the viewer enters the space, the forms and textures make it difficult to discern whether a fabric or a lamp floats above them live a cloud. Upon a closer inspection, it reveals to be thousands of styrofoam cups. Works like this are considered “site-responsive” in that a characteristic of the material of the site dictates the form of the resulting work. In this case, the soft, white appearance of the cups combined with their shape work to produce a specific effect for the space.

Utilizing the installation space to communicate and experience, Mexican artist Gabriel Dawe (born 1973) creates spiritual and culturally critical spaces for viewers to investigate. Plexus no. 19 (2012) and Plexus A1 (2015), for example, offers several critical insights into Mexican cultural norms in a way that transforms interior space into a spiritual shelter. Inside the Villa Olmo in Como, Italy, Dawe anchored threads to railings to span areas of the room, while illuminating them. The use of the material provides an ethereal, surreal visual effect that draws the viewer into the space to closer inspect and seek out new perspectives.

Physically the work appears as a colorful mist or dispersion of white light into its full spectrum of wavelengths. The impetus for this work was the desire to create a shelter for the human spirit. Thread is the basis of most clothing, what humans use to shelter their bodies. Dawe transcends this physical material to create shelter for the immaterial within us. The use of color was heavily influenced by the intense color commonplace in Mexican visual culture, but it carries significance in exploring gender politics as well. Finally, the adoption of thread represents the historical craft traditions of embroidery and intends on elevating their status into the realm of fine art.

Elements of New Media Art in Land Art

As you explore Land Art (called Earthworks by Robert Smithson) notice when you recognize the following elements of New Media Art:

- Expands the definition of art

- Remixing – uses images or things made by others in new ways

- Ephemeral – isn’t meant to or can’t last forever

- Collaborative – the artist is a facilitator and viewers make the art with them

- Connectivity – made possible because of new global connections

Despite the revolutionary strategies of Conceptual and Minimalist artists, their exhibitions were largely limited to art galleries. However, special consideration of the site became a point of emphasis in the conception and execution of artworks in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As early advocates, artists like Christo (1935-2020), Jean-Claude (1935-2009), and Robert Smithson (1938-1973) championed the avant-garde, site-specific movement. Artists like these conceived and created artworks as installations and environments instead of as objects. The experiential character of these works continued the subversive, artistic endeavor of challenging the relationships between spectator and spectacle, signifier and signified, viewer and artwork and artist. In some cases the art altered the significance of a space by its occupation, others used the expanded dimension(s) to enrich definition and consumption of sculpture, and in most cases the viewer is intended to become part of the piece in some manner.

Earthworks are unapologetically detached from the historical dependence on institutional framing for artwork. How much further can one get from the interior space of a metropolitan museum or gallery than designating it outside miles from civilization? Consequently, many of these undertakings are created in remote locations, requiring significant planning of part of the spectators, which likens their experience to that of a spiritual pilgrimage in nature with art. The transcendent nature of these works simultaneously unite nature and sculpture and nature and dissolve the boundary between art and life. This brand of site-specific art can be defined as an environmental construction that sculpturally utilizes materials to interact with the natural environment. Because of this connection to the natural world, these materials often are naturally occurring, like dirt, plants, water, and rocks. Similar to other ephemeral art forms, such as performance art, Earthworks are often documented only through photographs, film, and recordings.

One of the most early, notable, characteristic Earthworks of this character is Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), a construction of a 1,500 foot earth and stone platform projecting into the Great Salt Lake in Utah. Consisting of earthen materials, the archetypal shape of the spiral visually resembles both natural order – like the growth of nautilus shells and formations of galaxies – and human design with spiral symbols found in diverse, international communities throughout history. The shape itself is capable of endlessly curling, which suggests a duality of growth and decay, of creation and destruction. The symbolism continues. Smithson has suggested that the salty, mineral rich water and natural algae of the lake refers to both the primordial waters, which once brought forth life, and the dead sea that ended it. Additionally, the balance of alpha and omega is seen in the abandoned oil rigs dotting the shoreline (often not pictured images of the structure), which reminded Smithson of the dinosaur remains that brought forth their existence and the remains of vanished civilizations. Like many ephemeral works, Spiral Jetty is dynamic and transient; a spectator cannot see it the same at a different moment in time. The work evolves and changes. Smithson wished the work to represent the perpetual “coming and going of things” and ensured that no maintenance be exercised on the structure, allowing it subject to the natural order. There have been years where it has remained submerged, filled with colorful algae, and covered with crystallized salt.

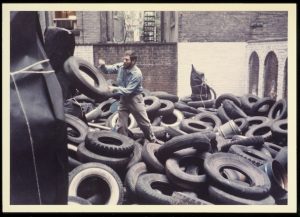

Bulgarian artist Christo Javacheff started his avant-garde trajectory in Paris, working within the circles of Nouveau Réalisme (new realism) – artists seeking to connect art with urban life, by rejecting the media associated with fine art in favor of everyday objects such common household items, print media, refuse. In this scene, Javacheff began experimenting with temporary works of art that often incorporated fabric. It was here that he began collaborating with Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon, a French artist interested in site-specific installations. Together the artists began going by their first names, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, and began working collaboratively wrapping objects from the size of motorcycles to the expansive scale of mother nature herself. These projects of envelopment can be considered political and a form of activism, referencing capitalism and consumer packaging.

Their first major undertaking of this nature was Wrapped Coast, One Million Square Feet (1968–69) in Little Bay near Sydney, Australia and the complex and laborious process ended up being just as noteworthy as the finished product. Christo and Jeanne-Claude worked with project coordinators, engineer), a team of rock climbers, and over 100 local art and architecture student workers and teachers. Together they overcame natural setbacks and engineering complications to wrap roughly one and a half miles of coast and cliffs with beige fabric, using 35 miles of rope.

A few years later Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s began another temporary, site-specific, environmental work titled Running Fence (1972-76) – an 18-foot tall, white, fabric fence that ran from the ocean at Bodega Bay through over 24 miles of rural and agricultural land. The process proved ultimately much more ambitious than One Million Square Feet, calling upon hundreds of workers, necessitating 18 public hearings, and the negotiation of agreements between dissenting landowners. While the Minimalist sculptural object, a seemingly endless ribbon of white cloth cutting through the natural environment, the most pioneering aspect of the work is arguably the process, the people involved, the engineering, and the significance of the site.

The adoption of site-specific and earthworks continued to develop internationally, as demonstrated in works like Walter De Maria’s (1935-2013) The Lightning Field (1977). Located in a desert in New Mexico, the physical work is essentially a 1-mile by 1-kilometer, rectangular grid of steel poles. These 400 poles with pointed tips can appear like an enormous bed of nails under most circumstances. However, during the electrical storms that frequently pass over the area, these poles act as conductors to concentrate lightning strikes into a spectacle. The work strikes an interesting balance of conceptual and minimalist artistic ideals, transforming the natural landscape into dynamic man-made and natural phenomenon.

Most of the works associated with Earth are art large, site-specific sculptures. However, English artist Andy Goldsworthy (born 1956) focuses also on small, intimate works of natural materials. These works were often composed of natural media, such as grass, rocks, leaves, flowers, bark, snow, ice, and water. Japanese maple (1987) was made by carefully stitching maple leaves into a ring and placed into a rocky pool. This particular piece was designed to communicate the splendor of natural phenomenon through a contrast in color, form, and texture. Works like these are created meticulously, photographed, and finally dispersed back into nature, a similar approach to that of Tibetan monks, who create sand mandalas. Goldsworthy’s ephemeral sculptures made of ice and snow carry similar messages. Often with Goldworthy’s fragile, transient works reflect his disposition as an environmentalist and thus car carry somber messages like a vanitas image from a 17th-century Dutch still-life painting.

Conclusions

As demonstrated in this chapter, many Minimalist and Conceptualist artists in the 1950s and 60s sought a schism from historical art-making processes. Since then many avant-garde artists further pronounced their departure through a variety of approaches: the dematerialization of art, the adoption of new media and technology, the reframing of historical art media, and the rejection of museums and gallery spaces though site-specific art and earthworks. While not mutually exclusive, the presence of these techniques carry on into contemporary art.

Key Takeaways

At the end of this chapter you will begin to:

- Deconstruct the motivations for artists to depart from two-dimensional media.

- Recognize the avenues of exploration light artists imagined in perception, light, color, and space.

- Assess the impact that the emphasis of dematerialization had on art production.

- Examine how the departure from two-dimensional media challenged the relationships between spectator and spectacle, signifier and signified, viewer and artwork and artist.

Selected Bibliography

Archer, Michael. Art Since 1960. 2nd ed. World of Art. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2002.

Beardsley, John. Earthworks and Beyond: Contemporary Art in Landscape. 4th Edition. New York: Abbeville Press, 2006.

Bishop, Claire. Installation Art: A Critical History. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Failing, Patricia. “James Turrell’s New York Light on the Universe.” Art News (April 1985): 71.

Judd, Donald. “Specific Objects.” Arts Yearbook 8 (1965): 74-82.

Lippard, Lucy R.. From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art. New York: Dutton, 1976.

Nochlin, Linda. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Art News 69 (January 1972): 22-39.

Smith, Terry. Contemporary Art: World of Currents. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2011.