Art and Dominant Culture

Elizabeth B. Pearce; Jessica N. Hampton; Hannah Morelos; and Katie Niemeyer

Art has been a part of history and daily lives for centuries, but what is considered “artistic” and valuable as defined by financial worth has been shaped by the same preferences and oppression that shape other aspects of our daily life. Many individuals face discrimination and underrepresentation based on their gender, race, sexuality, or other social characteristics. Even in the 20th century, we see the perceived differences between men and women’s art in the way that artists are often described in the media. Why is a woman referred to as a “female artist”? A person of color as a “Black photographer”? Or a “Latinx sculptor”? In contrast, when created by a White man, race and gender are not usually mentioned.

The topic of whiteness as the dominant culture can be an uncomfortable topic for many, while seeming quite obvious to others. Dominant culture expresses itself in the United States as the “typical” or “regular” way of being. Sometimes White people express that they don’t actually have a culture. This is part of the whiteness experience. When we describe this experience, it includes the power given to a particular group of people, and oppression to another group of people, otherwise known as White privilege. “White-washed art” can be described as giving privilege to a group of people based on their social characteristics and perpetuating a system that favors Euro-Americans (mostly White people).

When we talk about whiteness in art, it allows us the opportunity to peel back a layer of denial. Western expansion and dominance of Indigenous communities is one reason that there is a preference for White and westernized art and institutions. It is interesting to note that implicit bias, “the attitudes and stereotypes that affect our actions that we aren’t aware of, can affect how and what we feel and think about the word art when we hear it.”[1]

What do you think of when you think of “art”? An example of implicit bias would be when an individual from Western culture is asked about art, it is a relatively common bias to think about art in the context of dominant social characteristics. For example, social characteristics such as being “male” or being “White” are dominant in Western culture, especially in the United States. The David statue, created by one of the most famous and revered artists of the 14th century, Michelangelo Buonarroti of Florence, Italy, is commonly recognized and is one of the most famous sculptures in the world. The David sculpture is created by individuals possessing dominant social characteristics have made the arts, by association, a practice that is dominantly White and male. We learn early on as children in the U.S through our experience with social institutions.

Social institutions are complex systems that both influence their members and which can be influenced by individuals as well. For example, schools and museums are both examples of institutions in which children and families participate. They are exposed to art that is, for the most part, White and male-dominated through the selection process that has occurred throughout history. Increasing awareness of these biases has led to exhibitions and mentorship of individuals in underrepresented groups related to gender, ethnicity, race, sexuality, ability and other social characteristics. Individuals and allies contribute to institutions by advocating for change. Examples within this chapter show both the built-in biases and the ways in which artistic expression helps us move beyond socially constructed bias, preference, and ideas; this expands our definitions of art and beauty.

Art, Race, Ethnicity, and Culture

Ken Monkman is a North American artist well known for his paintings that reexamine the past. He frames his work by noting that these past experiences significantly influence the present. Monkman describes his use of visual art to examine the experience of Indigenous people in North America, both during the period of colonization and the effects on the present day families. His paintings depict the violence that European settlers acted upon Indigenous people, and the cultural beliefs that have been silenced. He creates works of art that tell the story from the perspective of those who were harmed and emphasizes the heroism of Indigenous families, the nonbinary aspect of gender they expressed, and other cultural aspects.

In the video below, Monkman describes his use of visual art to examine the experience of Indigenous people in North America, both during the period of colonization and the continued effects on the present day families.

Kehinde Wiley is another artist known for using his work to expose hypocrisies in the framing of European history, such as the Age of Reason, or Enlightenment period, which is known for its progress in liberty, universalism, separation of church and state, and freedom. This same time period is known for the colonialism of many Indigenous people and people of color, including Napoleon Bonaparte himself who reinstituted slavery in the French colonies a year after the famous Jacques-Louis David painting Bonaparte Crossing the Alps was painted.

Wiley’s re-interpretation of this painting, Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps, pictures a young Black man in the same pose, but in a way that questions the heroism and softens the military masculinity portrayed in the original. He confronts and critiques the portrayal of Black people in art.

The paintings hang side-by-side in the Brooklyn Museum, through May, 2020.

Art, Sex, and Gender

Art, reflective of society, has been work dominated by men. Men’s work was more likely to be sponsored, commissioned, featured, publicized and preserved. Women artists have often been seen as secondary. The well-known artist Frida Kahlo was a Mexican painter who was inspired by artifacts of her culture and used a folk art style. She explored themes of identity, postcolonialism, class, race, and gender. A prime example of marginalization taking place in Frida Kahlo’s lifetime happened when she lived in Detroit, married to a male artist named Diego Rivera. In Detroit, Frida Kahlo never showed her portraits in any exhibitions; however, she did get the opportunity to be interviewed. Although she was praised for her work through this opportunity, when the article came out it was titled “Wife of the Master Mural Painter Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art.”

Through this lens, Frida Kahlo was publicly known to her peers and the world as “Diego Rivera’s wife” and not as an artist. But Kahlo’s work surpassed Rivera’s in terms of artistic and social recognition. Kahlo died in 1954 at age 47, and her work became best known between the 1970s and 1990s. She is regarded as an icon of the Chicano civil rights movement, feminism, and the LGBTQ+ community.

Many paintings considered classic representations of ancient myths and events were painted by men. Carmen McCormack, a 2019 graduate of Oregon State University’s Bachelor of Fine Arts program, has recreated some works from a female, feminist, and lesbian perspective. For example, she has reinterpreted Francois Boucher’s 1741 painting, Leda and the Swan, which tells the story of the seduction or rape of Leda by Zeus in the form of a swan.

“I wanted to reinterpret that as a feminist, as a woman and as a contemporary painter,” McCormack said in an interview with the Corvallis Gazette-Times. “In the original (the women) were smiling, which is interesting for a male painter because it reinterprets the story of sexual violence — it’s not a happy thing.” McCormack’s version shows a dark, stormy background, and the women’s facial expressions and body language suggest more fear and resistance than does the original.

Centuries ago, genders were oppressed and underrepresented in their creative aspects. We can acknowledge that although there has been an improvement, there are still groups, genders, and individuals who face underrepresentation, discrimination, and oppression. New York is known as the hub of art and yet it is estimated that 76% to 96% of the art showcased in art galleries is by male artists. We can see that to this day there is a gender gap in the art industry that continues in the 21st century.

Film

Film, another visual medium, is a part of many family’s daily lives. Mainstream movies are accessible to Americans via many formats. Although women and people of color are represented in audiences in greater percentages than their population base, they are vastly underrepresented in lead roles both on and off screen. In 2018, only one female, Greta Gerwig, and one person of color, Jordan Peele, were nominated for Best Director in the Oscars competition. And in an analysis of speaking roles for women in the 900 most popular films from 2007 to 2016, fewer than one third of the roles went to women. Representation is worse for nonbinary people and when intersectionality of color and gender are examined.[2]

When a child goes into the movies, they are exposed to a variety of people. What most of these actors and actresses have in common is that they are White. As of 2017, only 20% of all lead actors and actresses on screen were people of color.[3] To the children watching these movies, this is the majority demographic being represented. When they do see a prominent character that looks like them, it shows them that they can fit into societal roles.

When movies such as Home, Black Panther, or Crazy Rich Asians came out, people of color flocked to see them. These movies lack obvious stereotypes, and people of color play leading roles. Movies with successful people of color are important because, without them, they are pushed to the back of the mind and this reinforces the dominant culture of White as the norm. When people of color are featured, parents have the chance to bring their children to see a main character with the same skin color or hair type as their own.

Tip, in Home, is a young African American girl with natural hair that helps save the day and gets her mom back home. Having a strong young child of color is important. In one study, researchers found that when preschoolers were asked to draw a main character from a fairy tale, most of the students drew a figure with blonde hair and light skin. This implies that these children, even the children of color, saw that White skin meant a happy ending.[4] In their minds, only blonde people with white skin were allowed to save the day and be stars.

- Figure 8.18. Typecasting in The Help

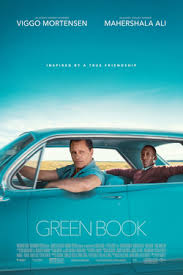

- Figure 8.19 Typecasting in The Greenbook.

Representation in movies also pertains to how the characters are portrayed. Do they follow common, sometimes derogatory, stereotypes? Are they seen as the villain? Are they the first to be killed? While a film may have a more diverse cast, when people of color are being represented through stereotypes or type casting (when a person is repeatedly cast for the same type of character, usually based on looks), it sheds a negative light on those people.

In March, 2020, the Washington Post magazine featured a project in which actors of minoritized groups were asked what kind of roles they typically were cast in, and what kind of roles they would like to play.[5] This powerful series emphasizes how easily stereotypes can be embedded in our minds. You can see Haruka Sakaguchi & Griselda San Martin’s full photography series at the Typecast Project.

Typecasting people contributes to the reinforcement of stereotypes of people of color and other minoritized groups; it emphasizes the centrality of White people both as the norm and as the keepers of interesting plot lines and life stories.

Representation of People of Color

How are people of color represented in visual mediums? And which people of color are prominent? Notice that when leading roles are cast in visual mediums, they are often people of lighter-colored skin. This is called “colorism” and is distinct from racism in that it shows a preference for the visual look, as opposed to implying that there is inferiority based on race.[6] A recent example is the prominence of Jennifer Lopez (J-Lo) and Shakira in the 2020 Super-Bowl half-time show. While both women are Latina, many people of color do not feel represented by lighter-skinned people who have dyed their hair blonde.

Understanding “isms”

Another way that film can help us to understand the world is to view how an “ism” affects a group that we are not a part of, such as understanding how women experience sexism, or Black people experience racism. But how do we identify which movies can help us understand what the actual experience is for the individual, and what “isms” feel like? One of the best ways is to listen to a member of the group that experiences it. Podcasts such as the 1A Movie Club’s program “‘The Help’ Doesn’t Help” in June, 2020, can help to explain how White-centered stories about racism fail to expose the actual experience of discrimination and to teach realistically and deeply. “White-centered” refers to stories which are told primarily from the White person’s point-of-view, with a lead or leads who are White, and sometimes feature what is called the “White saviour” meaning that it takes someone who is White to solve the problem, save the day, or otherwise fix some aspect of racism. Instead, the podcast hosts and guests recommend the following movies, amongst others:

- 13th (2016)

- Blackkklansman (2018)

- Get Out (2017)

- I Am Not Your Negro (2016)

- Just Mercy (2019)

- When They See Us (2019)

To listen to the 1A Movie Club’s lively discussion and debate about movies, Rotten Tomatoes and other movie rating systems, racism, health care, the racial empathy gap, history and current events, listen here.

Employment

While our discussion has focused on representation and on the effects that lack of representation has on families, it is important to mention employment. An obvious outcome of fewer people of color or other minoritized groups in media means people in these groups have fewer employment opportunities. A person who has multiple intersectional characteristics has even fewer options. In this one-minute video, actor Rosie Perez talks about how the intersectionality of being a woman of color, weight, hotness, ethnicity, and age affects her employment. Because movies influence so many consumers, the effects on Perez also indirectly affect the individuals and families who view media.

Perez takes a blunt approach in her description of social characteristics, especially related to age and to body size. She is conveying the message that while what is deemed “less desirable” by society may be acceptable for white males, it is less acceptable to have these traits as a woman of color. Her language may be triggering to some readers. The second video, from the group and YouTube channel “Film Courage” contains similar descriptions from actors and actresses of color.

These descriptions by Rosie Perez and other actors are supported by research. Family films made between 2006 and 2009 in the United States and Canada were studied specifically for gender bias, but also included appearance and age in the assessment. Beautiful women, with unrealistic body types, exposed skin, and waists so tiny that they would leave “little room for a womb or any other internal organs” are featured in these films with 14-24% possessing these features. In addition, it is most common for women to be under the age of 39 years (about 74%) with a higher percentage of men over the age of 40 years.[7]

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 8.15. “Napoleon Crossing the Alps” by Jacques-Louis David. Public domain.

Figure 8.16. “Poster – Frida Kahlo” by Vagner Borges. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 8.17. “Leda and the Swan” by François Boucher. Public domain.

Figure 8.20. “Adam Driver, John David Washington, and Director Spike Lee at the 2019 Critics’ Choice Awards” by Chris Miksanek. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 8.15. “Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps” (c) Kehinde Wiley. Image used under fair use.

Figure 8.16. “Coconuts” by Frida Kahlo (c) Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Image used under fair use.

Figure 8.17. “Leda and the Swan” (c) Carmen McCormack. Image used under fair use.

Figure 8.18. Screenshot from The Help (c) Walt Disney Studios. Image used under fair use.

Figure 8.19. Poster from the Green Book (c) Universal Studios. Image used under fair use.

“Shame and Prejudice: Artist Kent Monkman’s story of resilience” (c) University of Toronto. License Terms: Standard Youtube license.

“Rosie Perez on Roles for Women of Color” (c) PBS. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

- The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity (2015). Understanding implicit bias. Retrieved February 18, 2020, from http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/research/understanding-implicit-bias/ ↵

- Tan, S. (2018, February 28). This year's Oscar nominees are more diverse, but has Hollywood really changed? Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/entertainment/diversity-in-films/ ↵

- Statista. (2020, February 17). • Ethnicity of lead actors in movies in the U.S. 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2020, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/696850/lead-actors-films-ethnicity/ ↵

- Hurley, D. L. (2005). Seeing white: Children of color and the Disney fairy tale princess. The Journal of Negro Education, 74(3), 221–232. ↵

- Sakaguchi, H. & San Martin, G. (2020, March 4). How Hollywood sees me ... and how I want to be seen. Washington Post Magazine. https://www.washingtonpost.com/magazine/2020/03/04/actors-color-often-get-typecast-two-photographers-asked-them-depict-their-dream-roles-instead/ ↵

- Farrow, K. (2019, January 10). How the camera sees color. National Museum of African American History & Culture. Retrieved March 9, 2020, from https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/collection/how-camera-sees-color ↵

- Smith, S.L. & Choueiti, M. (n.d.). Gender disparity on Screen and behind the camera in family films. Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media. Retrieved June 2, 2020, from https://seejane.org/wp-content/uploads/full-study-gender-disparity-in-family-films-v2.pdf ↵

Unit of importance that meets the needs of society structured with defined rules and roles.

Meaning assigned to an object or event by mutual agreement (explicit or implicit) of the members of a society; can change over time and/or location.

May also appear as Xicano or Xicana. Chicano/a is an identity that people of Mexican descent who are born in the United States may choose for themselves. This term became popular in the United States during the Chicano Movement (El Movimiento) of the 1960s, when it was reclaimed as an act of resistance to assimilationist narratives. It has a unique meaning from “Mexican-American,” although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably.

The materials and supplies used to create a piece of art, such as paint or clay. May also describe categories of art, such as a painting or sculpture.

Prejudice or discrimination that favors people with lighter skin over those with darker skin, especially within a racial or ethnic group.