Health and Health Insurance

Elizabeth B. Pearce; Jessica N. Hampton; and Christopher Byers

Industrialized nations throughout the world, with the notable exception of the United States, provide their citizens with some form of national health care and national health insurance.[1] Although their healthcare systems differ in several respects, their governments pay all or most of the costs for health care, drugs, and other health needs. In Denmark, for example, the government provides free medical care and hospitalization for the entire population and pays for some medications and some dental care. In France, the government pays for some of the medical, hospitalization, and medication costs for most people and all these expenses for the poor, unemployed, and children under the age of ten. In Great Britain, the National Health Service pays most medical costs for the population, including medical care, hospitalization, prescriptions, dental care, and eyeglasses. In Canada, the National Health Insurance system also pays for most medical costs. Patients do not even receive bills from their physicians, who instead are paid by the government. Medical debt and bankruptcy due to accident or disease is a uniquely American problem.

These national health insurance programs are commonly credited with reducing infant mortality, extending life expectancy, and, more generally, for enabling their citizenries to have relatively good health. Notably, the United States ranks 33 out of 36 countries who belong to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for infant mortality. The infant mortality rate in the United States is 5.9 deaths per 1,000 live infant births, as compared to the average rate of 3.9 deaths per 1000 births. Five countries have death rates lower than 2 per 1,000 births. Their populations are generally healthier than Americans, even though healthcare spending is much higher per capita in the United States than in these other nations. In all these respects, these national health insurance systems offer several advantages over the healthcare model found in the United States.[2]

The Role of Health Insurance in the United States

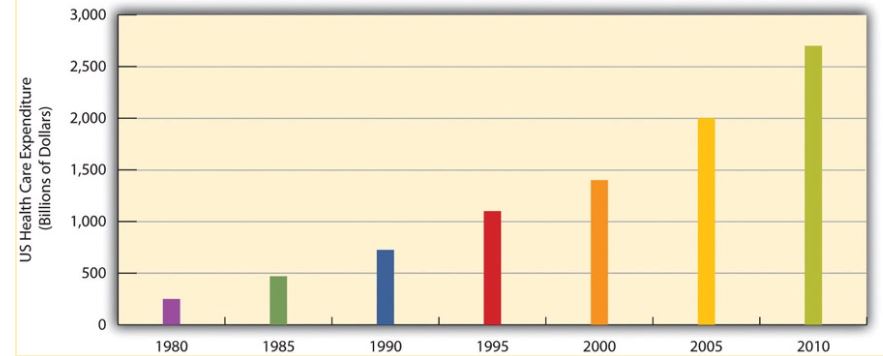

Medicine in the United States is big business. Expenditures for health care, health research, and other health items and services have risen sharply in recent decades, having increased tenfold since 1980, and now cost the nation more than $2.6 trillion annually. This translates to the largest figure per capita in the industrial world. Despite this expenditure, the United States lags behind many other industrialized nations in several important health indicators.

US Health-Care Expenditure, 1980–2010 (in Billions of Dollars)

Access to Health Care Coverage and Insurance

There are many insurance options in America, and we will see that they disproportionately benefit some and disadvantage others based on factors like sex, income, geographical location, and ethnicity. In 2017, some of the most common ways people accessed insurance was through private plans; employer-based (56%), direct purchase (16%), or, through government plans; Medicaid (19.3%), Medicare (17.2%), and military healthcare (4.8%).[3]

To learn more about how people accessed health insurance coverage, and who remained uncovered, watch this seven-minute video provided by the United States Census Bureau.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was created to make healthcare more affordable and to be less discriminatory in 2010. In 2016, section 1557 provided new regulations to the Affordable Care Act, including a way to enforce civil rights protections in healthcare by making it unlawful for health care entities to discriminate against protected populations if they receive any type of federal financial assistance. This included health insurance companies participating in the Health Insurance Marketplaces, providers who accept Medicare, Medicaid, and Child Health Insurance Program (CHIP) payments, and any state or local healthcare agencies, among others. This marked the first time that discriminatory practices on the basis of race, skin color, national origin, age, sex, disability status–and in some cases, sexuality and gender identity–were broadly prohibited in the arena of public and private healthcare.[4]

Some of the common ways that lower income families and individuals access insurance in Oregon are through programs like Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Programs (CHIP): which is referred to as Oregon Health plan (OHP) in Oregon.

| Family Size | OHP for Adults | OHP for Children |

| 1 | $1,396/month | $3,086/month |

| 2 | $1,893/month | $4,184/month |

| 3 | $2,390/month | $5,282/month |

| 4 | $2,887/month | $6,380/month |

| 5 | $3,383/month | $7,478/month |

| 6 | $3,880/month | $8,576/month |

Medicaid is a federal and state funded program that is managed by individual states. It provides government insurance to those who need it. Each state has the power to decide who is eligible for it, and most states focus on low-income individuals, and those with disabilities. With the expansion of the ACA in 2014, states had the choice to expand their Medicaid to serve more citizens; Oregon is one of 37 states that elected to do so. For up to date information on each state, consult this Kaiser Family Foundation interactive map and narrative.

Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map

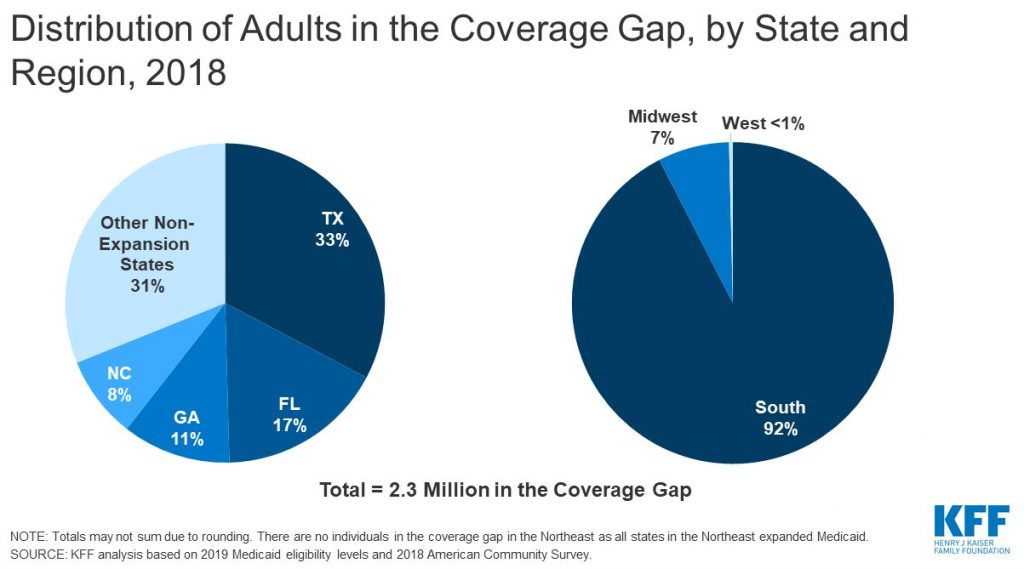

The U.S. government’s website about Medicaid (https://www.medicaid.gov) provides state by state report cards on a wide variety of health access and health quality measures. This variance in Medicaid eligibility creates great inequity for low-income families based on location. Those in states that have not expanded Medicaid face a much larger “coverage gap,” meaning that many more families do not have access to health care insurance.[6]

Those who are age sixty-five or older can access healthcare insurance through Medicare, which is federally funded. Medicare covers about half of health care expenses for those enrolled, and many retirees who can afford to do so purchase private insurance or purchase additional coverage from Medicare itself to cover the gap.[7]

Case Study: Getting Tested for Coronavirus

Carmen Quinero, a 35-year-old essential worker who works at a distribution center that ships N95 masks in California, developed a severe enough cough in late March, 2020, that the human resources department at her workplace told her to go home and not to come back to work until she was tested for the virus. Quinero has health insurance coverage through her employer; she has a $3,500 deductible.

Tests were not widely available at this time, so she was directed by her doctor to go to an emergency room. She went to the closest one, a for-profit hospital owned by Universal Health Services, one of the largest healthcare management companies in the United States. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (aka CARES Act) had passed the week before, and it had been widely publicized that coronavirus testing and treatment would be free to individuals and covered by the federal government.

Unfortunately, the legislation is full of loopholes, including for people like Quinero who need a test but were unable to get one due to the low supplies. Although she was given a chest x-ray and prescribed an inhaler, she was not tested. That means that not only was she responsible for the $1,840 in hospital and doctor fees, but she had to miss a week of work (mostly unpaid), putting a considerable financial strain on Quinero and her family.

Quinero’s case is not isolated and is not specific to the coronavirus. Access to, and coverage for, the test for the novel coronavirus (aka COVID-19) within the pandemic illustrates how the patchwork of insurance, government programs and laws, and private payments inequitably affects lower-income people, whether or not they have health insurance coverage.

To hear more about Carmen’s story, listen to this four minute recording from the NPR-KFF series Bill of the Month.

Who is Left Out?

Most of the uninsured (84.6 %) in the United States are working age adults aged 19 to 64 years old. Men are overrepresented in these numbers; over half of all people without health insurance coverage were male (54.6 percent), even though the U.S. population has more women than men. The uninsured are disproportionately concentrated in the South.[8] The number of people without health insurance has been increasing steadily since 2016; 8.5% of all Americans (27.5 million people) did not have health insurance at any point in the year of 2018, according to the American Community Survey.[9]

Socioeconomic status plays a large part in access to healthcare. Occupation, education level, and chronic poverty all play contributing roles. The unique structure of tying health care insurance to full-time employment in the United States perpetuates income equality. Income ties into important social determinants of health including location of home, transportation, and quality of life. Medicaid, which is tied to income level, has limited medical coverage, and often does not cover dental or vision care for adults. Plans vary from state to state. Children, older adults, and people of color are disproportionately affected by health inequities.[10] For greater detail on adults aged 18-64 who are uninsured, review this 2019 report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

A separate study showed that before the expansion of the ACA in 2014, about 41% of Hispanics, 26% of Blacks, and 15% of Whites were uninsured, while after expansion the rate of uninsured individuals decreased by 7% for Hispanics, 5% for Blacks, and 3% for Whites.[11] Although the difference in rates for those un-insuranced have closed,[12] there is still a sizable gap that needs to be addressed in order to effectively address equity in access to health care. Even with these improvements, vast inequities exist state to state, because a family who is poor enough to receive Medicaid in one state is not “poor enough” in another state, especially those who have not expanded Medicaid. Geography matters. Although our country has a rhetoric of equality, family and health laws vary significantly state to state, which reinforces inequalities. Eligibility ranges from having an income that is 40% of the Federal Poverty Line (FPL) to having an income that is 138% of the FPL: quite a difference!

Lack of health insurance has significant consequences because people are less likely to receive preventive health care and care for various conditions and illnesses. For example, because uninsured Americans are less likely than those with private insurance to receive cancer screenings, they are more likely to be diagnosed with more advanced cancer rather than an earlier stage of cancer.[13] In an analysis published in 2009, researchers found that there was a 25% higher risk of death for adults (aged 17 to 64) who were uninsured than those who had private insurance.[14]

Research and Drug Access

Pharmaceutical research and sales are a gargantuan business in the United States. The cost of developing any single new drug is estimated to be about one billion dollars. Financing comes from the federal government and philanthropic organizations at the discovery research level; large sums of money are pumped into the initial stage of medication research.[15]

Later-stage development is typically funded by pharmaceutical companies, which can be for for-profit companies or nonprofit companies. For-profit companies may be funded by venture capitalists or as a part of larger corporations. Funding for nonprofit companies is a bit trickier; gaining access to federal and foundation funding takes staff time and expertise. The unequal and inequitable funding opportunities put nonprofits at a disadvantage, because they have to invest more time in writing requests for grants and funding from government corporations.

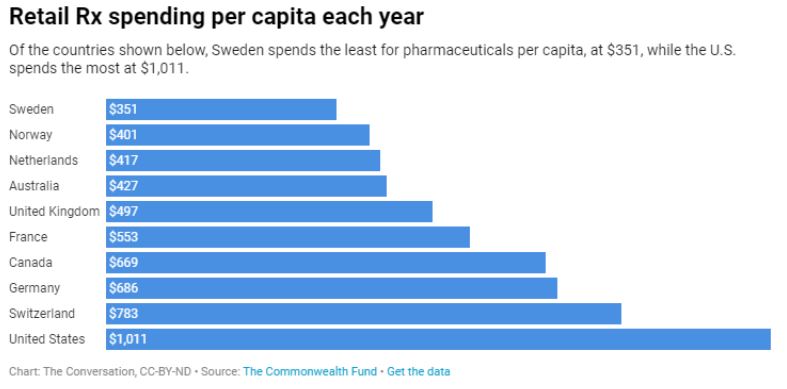

The cost of drugs in the United States increased dramatically starting in the 1990s. It is important to note that American families are not accessing more medications than people in comparative countries. In fact, Americans use fewer prescription drugs and are more likely to use less expensive generic prescriptions. It really comes down to price per pill; they simply cost more in the United States than in other countries.[16]

For-profit pharmacological companies have the upper hand in terms of distribution and overall influence on the decisions for research and funding for new medications in the United States. A company that has a mission of profit for its employees and public shareholders could be seen as having an ethical dilemma when selling its product might benefit those groups, but may not be the best course of action for the people who need those medicines to maintain their basic health. It is for this reason that most countries (excluding the United States) do not allow drug research companies to profit and create state contracts with those companies in order to keep costs low.[17]

In Focus: The Opioid Epidemic

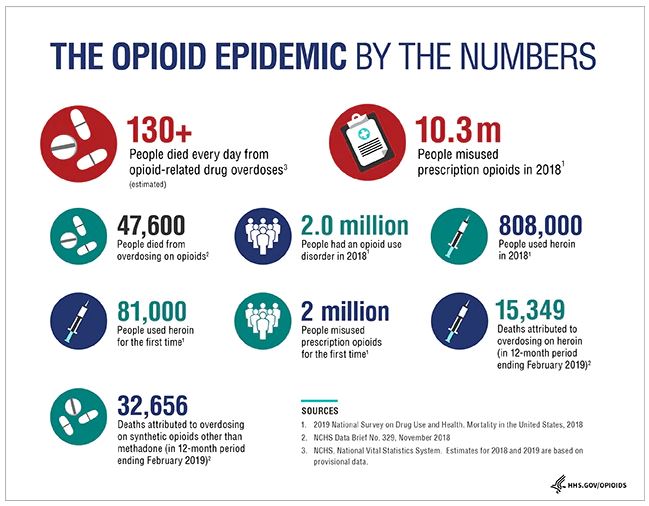

An example of the power of for-profit drug companies can be found in the opioid epidemic. The opioid epidemic began in the United States in the 1940s. While medications like heroin and morphine have been used for pain management for thousands of years, they became more popular during World War II, when heroin and morphine were used to treat war veterans and people who have experienced trauma and wounds from battle.

Families in the United States with members who have difficulty navigating proper pain management have found opioids to be one solution. Prescriptions for these medications were given out and dispensed very generously, even for temporary pain, starting in the mid-20th century. As usage increased dramatically in the 1990s, pharmaceutical companies assured the medical community and patients that these drugs were not addictive.[18] It is now known that addiction to these opioids and other substances often starts with prescription medications and progresses to a more dangerous level of use if left unchecked.

Private lawsuits and governmental action against pharmaceutical companies began to emerge in the early 2000s in the United States. It has been found that companies failed to follow government regulations related to drug production and regulation such as tracking and investigating suspicious orders of these medications. Both name-brand (e.g. Oxycodone) and generic drug manufacturers were guilty of these actions, although generic manufacturers remained unchecked for longer. Companies made billions of dollars of profits during this same period of time.[19]

Lawsuits against drug companies and distributors by the federal government, multiple states, Native American tribes, and local municipalities show promise for compensation. Examples include allegations of deceptive business practices, fraud, lax monitoring, and oversaturation of the market.[20] These actions resulted in not only individual negative consequences but have also contributed to systemic breakdown in communities.

The ripple effects on families and communities are difficult to quantify. While overdoses and deaths can be counted, loss and grief is immeasurable. Diminished parenting, loss of employment, loss of housing, and broken relationships all affect families, schools, workplaces, and communities. The effects of drug addiction and trauma are generational; we will not know how many families have been affected by this multi-century epidemic until well into the future.

Keeping our Families Healthy

If you were to spend a few minutes brainstorming a list, what would you include as the most important requirements to keeping your family healthy? While this chapter has focused on health care and health insurance as important aspects of health management, the authors of this text would like to emphasize that health care starts with access and decision-making related to exercise, diet, relationships, work, sleep, intellectual stimulation, addictive substances, education, and social life. This is our list; perhaps you have other aspects to add!

Importantly, those individual and family decisions are directly impacted by the social institutions and processes at the core of the United States. Past and present laws, policies, practices, and biases that create and reinforce inequities mean that families live with vastly different access to resources, including food, safe and stimulating outdoor environments, time, work environments, social life, and health care.

For example, many families live without easy access to recreational trails and playgrounds. The Housing Now chapter of this text details the ways in which laws, regulations, and lending corporations have actively participated in pushing minoritized racial-ethnic groups into these areas. We must pay attention to these past practices and the ways that they impact present families’ health. During the current (2020) COVID-19 Pandemic, it is becoming clear that the virus is transmitted more easily in crowded spaces indoors than in the outdoors. There is a disproportionate number of coronavirus cases and deaths amongst minoritized populations in the United States[21], and it is possible that lack of access to outdoor spaces plays a role. So at the same time that this lack of resources makes it more difficult to maintain everyday physical and mental health, it may also contribute to illness, hospitalization, loss of employment, and even death during the pandemic.

This video from the American Medical Association features an interview with Doctor Aletha Maybank and explains how funding, data collection and the overlap with structural discrimination affect the rates of the virus.

Institutionalized inequities have been amplified during the current pandemic. Crowded work environments such as meat-packing facilities; food deserts; less health insurance, less access to health care and virus testing as measured by geography and transportation options; and greater likelihood to experience discrimination, stress, and lack of sleep, are some of the factors that contribute to greater numbers of Black, Native, and Latinx families being affected by the COVID-10 virus.[22] These overlapping factors are discussed throughout this text.

It is important to recognize the role of activism in alleviating all social problems, including the problem experienced by so many families in the United States: poor health that could be improved by adequate health care. There is hope; there are many countries that have differing successful models of health care that give all citizens access. In this country there are multiple groups, many led by physicians or other medical professionals, that are working to create and/or modify systems so that all individuals and families can access the basic health care that they need. Two organizations that are prominent are Health Care for ALL Oregon and Physicians for a National Health Program.

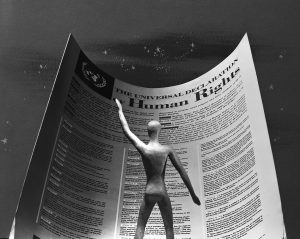

The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights Article 25 identifies health as a human right.

Article 25.

(1) Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

(2) Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. All children, whether born in or out of wedlock, shall enjoy the same social protection.[23]

Some non-industrialized nations and all industrialized nations, with the United States as the notable exception, have adopted some form of universal healthcare system since the 1948 adoption of this Declaration. The irony is that the framework for the human rights declaration came from the United States and the work of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his wife and Statesperson Eleanor Roosevelt.[24] The United States does not have an actual health care system, but rather multiple systems of health insurance accessed: via employment, via family configuration as defined by government structures, state-funded block programs, and federal programs for specific groups such as people who are indigent, disabled, or older. In other words, not all families.

While families in the United States strive to make the best choices for themselves, they are limited by the existing access to resources needed to be as healthy as possible. Some of these inequities were created by past laws and practices. But those, and others, can be adjusted and changed. The societal and governmental commitment to the standards of health and well-being as identified in the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights is a way to begin.

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Health Care and Health Insurance: A Comparison” is adapted from “Global Aspects of Health and Health Care” in Social Problems by Anonymous. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adaptation: edited for clarity and accuracy.

Figure 3.10. “US Health-Care Expenditure, 1980–2010 (in Billions of Dollars)” in Social Problems by Anonymous. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Based on data from Statistical Abstracts/U.S. Census.

Figure 3.11. “Distribution of Adults in the Coverage Gap, by State and Region, 2018” by Peterson-KFF. License: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Figure 3.12. “Chicago, 2012” by gregorywass. License: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Figure 3.14. “Money Behind Health Care” by Truthout. License: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Figure 3.15. “Retail RX spending per capita each year” by The Conversation. License: CC BY-ND 4.0. Based on data from The Commonwealth Fund.

Figure 3.16. “The Opioid Epidemic by the Numbers” by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Public domain.

Figure 3.18. “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” by the United Nations. License: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Income, Poverty and Health Insurance – Health Insurance Presentation” by US Census Bureau. Public domain.

Open Content, Original

Figure 3.13. Image by Katie Niemeyer. License: CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 3.17. “COVID-19: Physical Distancing in Public Parks and Trails” (c) National Recreation and Park Association. Image used with permission.

“COVID-19 Update for April 21, 2020” (c) American Medical Association. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

- Russell, J. W. (2018). Double standard: Social policy in Europe and the United States (Fourth edition). Rowman & Littlefield. ↵

- Reid, T. R. (2010). The healing of America: A global quest for better, cheaper, and fairer health care. Penguin Books. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). Coverage numbers and rates by type of health insurance: 2013, 2016, and 2017 [table]. Retrieved June 8, 2020, from https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/p60/264/table1.pdf ↵

- Rosenbaum, S. (2016, September). The Affordable care act and civil rights: The challenge of Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act. Milbank Quarterly, 94. https://www.milbank.org/quarterly/articles/affordable-care-act-civil-rights-challenge-section-1557-affordable-care-act/ ↵

- Health Plans in Oregon. (2020). Oregon health plans made easy. https://www.healthplansinoregon.com/oregon-health-plan-made-easy/ ↵

- Garfield, R., Orgera, K., & Damico, A. (2020, January 14). The Coverage gap: Uninsured poor adults in states that do not expand Medicaid. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/ ↵

- MedPac. (2020, March). Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar20_entirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0 ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2018, September 12). Who are the uninsured? . Retrieved June 9, 2020, from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/09/who-are-the-uninsured.html ↵

- Berchick, E. R., Barnett, J. C., & Upton, R. D. (November, 2020). Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2018. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-267.html ↵

- Keenan, P. S., & Vistnes, J. P. (2019, June). Research findings: Non-elderly adults ever uninsured during the calendar year, 2013–2016. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/rf42/rf42.shtml ↵

- Buchmueller, T. C., Levinson, Z. M., Levy, H. G., & Wolfe, B. L. (2016). Effect of the affordable care act on racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage. American Journal of Public Health, 106(8), 1416–1421. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303155 ↵

- Inserro, A. (2018, September 11). ACA pushed uninsured rate down to 10% in 2016. American Journal of Managed Care. https://www.ajmc.com/newsroom/aca-pushed-uninsured-rate-down-to-10-in-2016-even-more-so-in-medicaid-expansion-states ↵

- Halpern, M. T., Ward, E. M., Pavluck, A. L., Schrag, N. M., Bian, J., & Chen, A. Y. (2008). Association of insurance status and ethnicity with cancer stage at diagnosis for 12 cancer sites: A retrospective analysis. The Lancet Oncology, 9(3), 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70032-9 ↵

- Wilper, A. P., Woolhandler, S., Lasser, K. E., McCormick, D., Bor, D. H., & Himmelstein, D. U. (2009). Health insurance and mortality in us adults. American Journal of Public Health, 99(12), 2289–2295. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.157685 ↵

- Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Drug Discovery, Development, and Translation. (2009). Current model for financing drug development: From concept through approval. National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK50972/ ↵

- Haeder, S. F. (2019, February 7). Why the US has higher drug prices than other countries. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/why-the-us-has-higher-drug-prices-than-other-countries-111256 ↵

- Gross, D. J., Ratner, J., Perez, J., & Glavin, S. L. (1994). International pharmaceutical spending controls: France, Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Health Care Financing Review, 15(3), 127–140. ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (September, 2019). About the epidemic. Retrieved July 2, 2020, from https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/index.html ↵

- Yerby, N. (2020, June 18). DEA database shows generic drug manufacturers contributed most to the opioid epidemic. AddictionCenter.com https://www.addictioncenter.com/news/2019/08/generic-drug-manufacturers-opioid-epidemic/ ↵

- Haffajee, R. L., & Mello, M. M. (2017). Drug companies’ liability for the opioid epidemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(24), 2301–2305. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1710756 ↵

- Godoy, M. and Wood, D. (2020, May 30). Growing data show Black And Latino Americans bear the brunt. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/05/30/865413079/what-do-coronavirus-racial-disparities-look-like-state-by-state ↵

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, June 25). COVID-19 in racial and ethnic minority groups. Retrieved July 4, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html ↵

- United Nations. (1948, December 10). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved July 4, 2020, from https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ ↵

- Gerisch, M. (n.d.). Health care as a human right. Human Rights Magazine, 43(3). Retrieved July 4, 2020, from https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/the-state-of-healthcare-in-the-united-states/health-care-as-a-human-right/ ↵

Lack of fair treatment, opportunity, or conditions.

The combination of one’s social and economic status, specifically related to income, education, and career or job status.