10 Dentin-pulp complex development

- Overview

- Dentinogenesis

- Induction

- Apposition

- Maturation

- Types of dentin

- Clinical considerations of dentinogenesis

- Pulp

- Anatomy

- Microscopic features

- Clinical considerations of pulp

Overview

Dentin and pulp are covered together because of their shared lineage: they are derived from the neuro-mesenchyme of the dental papilla. Dentin resembles enamel chemically. But don’t focus too much on chemical composition by weight. Humans are made up of mostly the same atoms as thalidomide— the morphology of those atoms matters! By the end of this chapter you should see similarities between dentin and pulp. The two are often referred together as the dentin-pulp complex.

One important concept in this chapter involve the cells in (or near) dentin. The ECM of dentin contains long tunnels filled with fluid and cytoplasmic extensions of dentin-producing cells, the odontoblasts. These are significant when it comes to dental hypersensitivity, as well as in the repair of dentin following damage.

Another major concept involves focusing on the ECM of dentin. Like the formation of enamel matrix, studying how dentin matrix is formed teaches us about how it can be repaired. Unlike enamel, dentin can be repaired by cellular activity after eruption. As a result, dentin comes in forms made before birth, shortly after birth, and long after birth. Before you get too comfortable thinking that means there are only 3 types of dentin, be aware there are multiple forms made both before and after birth. Enamel only comes in one form: the stuff made during the embryonic period.

"Histological section of tooth" by Doc. RNDr. Josef Reischig, CSc. is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 / labels addedDentin formation

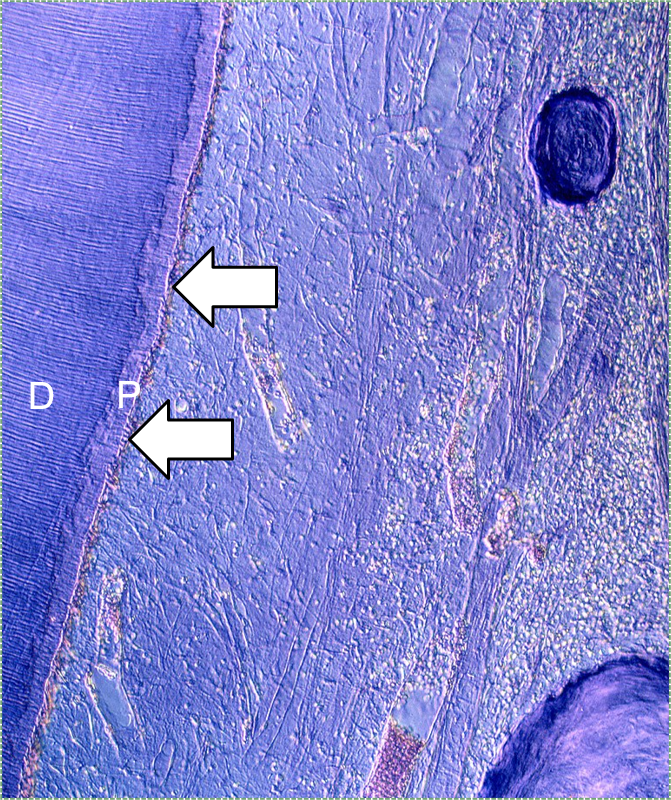

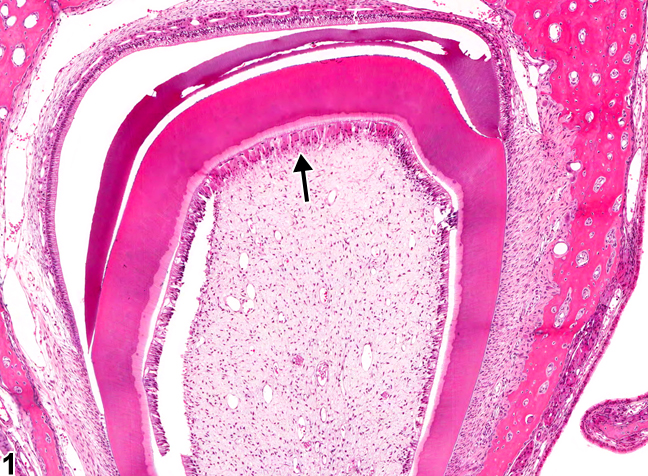

Dentinogenesis is the process of dentin formation (and should not be confused with the word odontogenesis). Dentinogenesis begins during the bell stage of tooth development. Odontoblasts (arrows in Fig. 10.2) are the cells that produce dentin. The first step is the secretion of proteins, including collagen←, which act as a scaffold←. The second step is mineralization around the scaffold. The initial protein-rich material is pre-dentin (P in Fig. 10.2), after it mineralizes it is called dentin (D in Fig. 10.2). Unlike amelogenesis, there is no third step of protein removal (remodeling).

Induction (or initiation)

During the induction phase, the odontoblasts appear. This happens in the bell stage of tooth development, as the enamel organ grows around the dental papilla. Cells of the IEE differentiate← into pre-ameloblasts and secrete morphogens←, including BMP. The closest neuro-mesenchymal stem cells of the dental papilla receive BMP morphogens and differentiate into odontoblasts. Odontoblast differentiation involves a morphological change. The amorphous neuro-mesenchymal stem cells line up, forming what looks like a simple cuboidal epithelium←, complete with apical-to-basal polarity←. This sort of polarization is unusual for a connective tissue. Odontoblasts, however, are not derived from mesoderm, they are derived from neuro-mesenchyme. It is common for neurons and glial cells to be polarized, and odontoblasts share this morphology. Inside odontoblasts, large amounts of rER← and Golgi apparatus← are forming in preparation for the secretion of large amounts of protein.

Apposition

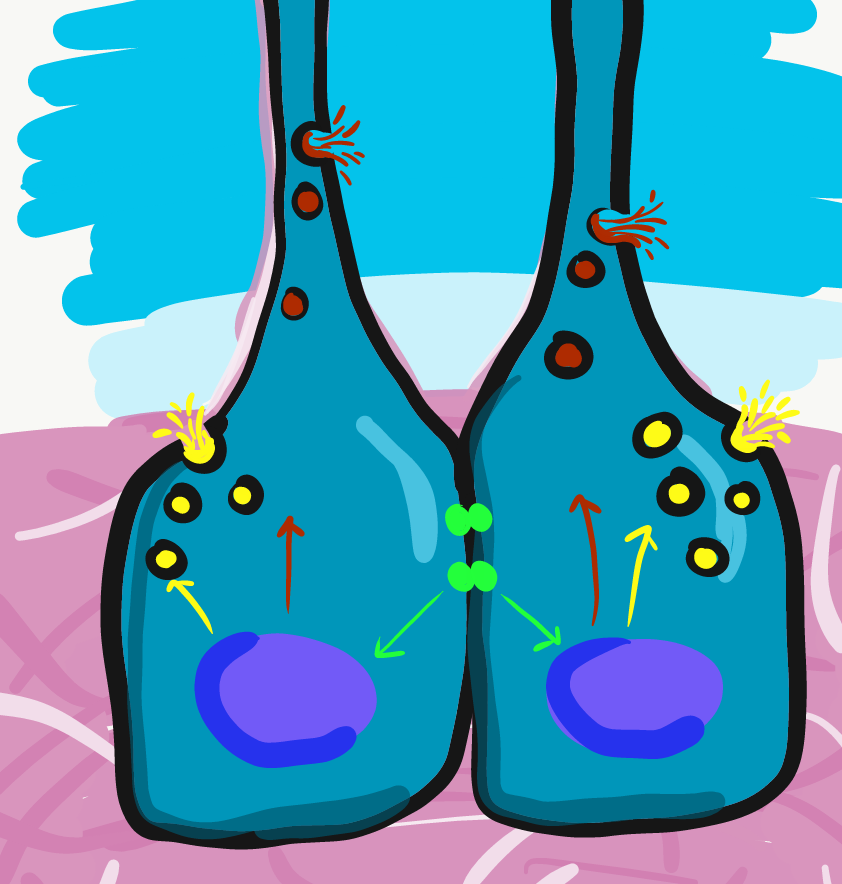

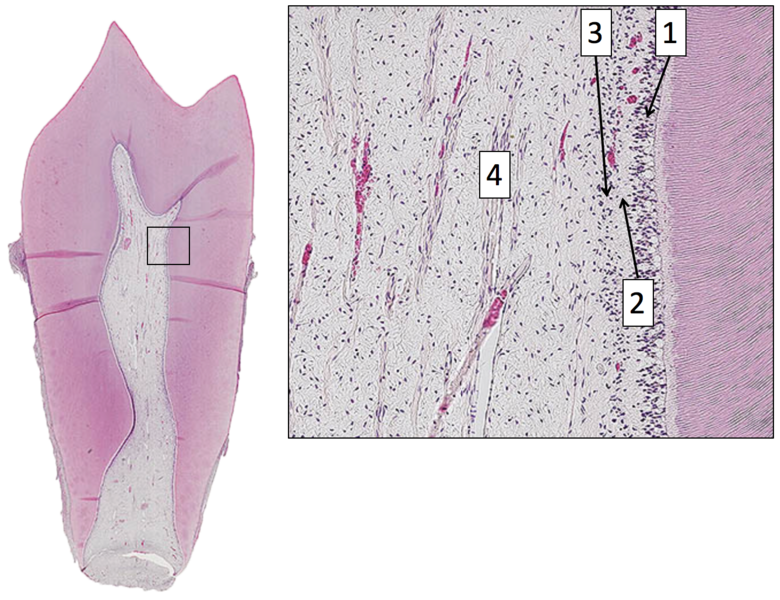

Newly formed odontoblasts begin secreting proteins that act as a scaffold←. This scaffold guides the mineralization of dentin. The initial protein-rich substance is pre-dentin (lighter blue layer in Fig. 10.4). It is mostly collagen← plus a few other dentin-specific proteins. Pre-dentin mineralizes later. Calcium and phosphate react in pre-dentin to form calcium hydroxyapatite crystals, similar to enamel and bone tissue← (darker blue layer in Fig 10.4). As layers of dentin mineralize, odontoblasts continue secreting new pre-dentin, pushing the layer of odontoblast cell bodies deeper into the jaw (Fig. 10.3). Unlike ameloblasts, odontoblasts leave behind an odontoblastic process in the dentin they secrete. This arm-like extension contacts nearly every layer of dentin that odontoblast creates. Because dentin mineralizes around the odontoblastic process, a dentinal tubule runs through nearly the entire length of dentin. If you removed the odontoblasts, dentin would be perforated by millions of hollow tubes (Fig. 10.8).

Collagen← and dentin-specific proteins are secreted by the side of the odontoblast cell body facing the enamel (yellow vesicles, Fig 10.4). This ensures the cell body does not get cemented in place by hard dentin, and instead always touches a thin layer of gelatinous pre-dentin. Glycoproteins and enzymes like matrix metalloproteinase are secreted a short distance up the odontoblastic process (less than 1 mm, brown vesicles in Fig. 10.4) which trigger mineralization of dentin. This traps the odontoblastic process within mineralized dentin, but leaves the cell body free to move.

Figure 10.5: Histology of the dentin-enamel junction, with an enamel tuft indicated (pink arrow). Image credit: "Histologic cross-section of tooth showing enamel, labeled A, and dentin, labeled B." by Dozenist is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 / cropped and arrow added

A few odontoblastic processes extend past the DEJ. They become trapped in enamel after amelogenesis begins (which happens after dentinogenesis). These are known as enamel spindles. Both enamel spindles, and the bushier-looking enamel tufts (Fig. 10.5) are referred to as hypo-mineralized regions or defects in enamel. There is something important missing in those descriptions, however. Teeth that exert more force have more enamel tufts (such as human molars, or the teeth of animals who eat nuts), suggesting enamel tufts strengthen enamel. It is not impossible for enamel spindles and tufts to both be less mineralized and increase the strength of enamel. Recall how hard but brittle calcium hydroxyapatite crystals of bone tissue← are strengthened by the flexible protein collagen←. It is also attractive to hypothesize enamel spindles and tufts act similar to the interdigitation of rete pegs← and dermal papillae← in the skin and oral mucosa.

"Figure 1a" by Monaogna Vangala is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 / labels addedDentin mineralizes in one of two ways: in globs or in lines. The first dentin produced mineralizes in globs because extra-large collagen← fibers are secreted in spheres (there are older theories of what spherical globs are made of). Around the collagen globs, pre-dentin mineralize into mature dentin. Some regions do not mineralize fully, and are called inter-globular dentin. The fully mineralized dentin found between inter-globular dentin is globular dentin. Globular and inter-globular dentin are visible between mantle dentin and circum-pulpal dentin (see below). Low levels of phosphate during the first trimester can increase the amount of inter-globular dentin.

After the first collagen fibers are secreted in globs, fibers are lengthened by odontoblasts. This dentin mineralizes more uniformly, one layer at a time, in a process called linear mineralization. In regions that mineralize linearly, collagen fibers run parallel to each other, but perpendicular to the dentinal tubules. Only after linear mineralization begins do odontoblasts leave behind an odontoblastic process.

The lines that should be clearly visible in the layer of dentin in Fig. 10.6 are dentinal tubules, the tubes in which the odontoblastic process are found. Notice that they do not run in a straight line. Odontoblasts, like ameloblasts, move in a slightly curved direction as they produce ECM. Like the curves you see on most bridges, this curvature is no accident. Curves increase the strength of dentin. The large curves are called the primary curvature. If you zoomed out you would see the primary curvature has a sinusoidal (S) shape. The curvature is more pronounced in the crown than the root. If you zoomed in on a single odontoblastic process, you might see areas where it briefly curves opposite of the primary curvature. That is called a secondary curvature. In contrast, the bending of enamel rods has no names for bigger or smaller curves.

Similar to the formation of enamel, odontoblasts undergo daily patterns of faster and slower pre-dentin deposition. As a result, light and dark bands are visible in dentin, called the Imbrication lines of Von Ebner (or the incremental lines of Von Ebner). The Imbrication lines of Von Ebner are comparable to the Lines of Retzius in enamel. Don’t ask how Retzius discovered lines in enamel but missed the same pattern in dentin a few millimeters away, leaving it to Von Ebner to name a hundred years later. People get credited for re-discovering things all the time. These should both be renamed incremental lines in enamel and the incremental lines in dentin, anyway. Furthermore, prominent imbrication lines can be called contour lines of Owen. This includes the neonatal line, similar to the one found in enamel. These represent big changes in nutrition that lead to changes in the density of dentin produced that day. You can read part of Owen’s treatise on the comparative anatomy of the tooth, someone scanned 30 pages if you are curious about what it was like to learn histology without pictures.

Maturation

Unlike enamel, dentin does not undergo significant changes after it mineralizes. As a result, some textbooks call the mineralization of pre-dentin into dentin as the “maturation” step, while others (including this one) have chosen to use the words apposition and maturation consistently. Why do ameloblasts take an extra step removing some scaffolding← after mineralization occurs, and odontoblasts do not? One possibility is ameloblasts are epithelial cells, and epithelia generally secrete very little ECM. Perhaps they are not very good at it. In contrast, odontoblasts differentiate← from neuro-mesenchymal stem cells. It is likely during their epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition← they unpack genes that make them efficient at creating ECM. A second possibility is that the high percentage of minerals in mature enamel (96%) can only occur after protein scaffolding is removed. Remember, calcium and phosphate react to form crystals on their own, but to get these crystals to adopt the morphology of a tooth requires scaffolds. The reason is not as important as the illustration of another difference between enamel and dentin due to their different cell lineages.

Classification of dentin

In Fig. 10.8, dentinal tubules should be easily visible. In a living tooth, each tubule contains an odontoblastic process. Not all regions of dentin are the same, and there are several ways of classifying different types of dentin. One way to classify different types of dentin is based on how close the dentin is to a dentinal tubule. The thin white area of dentin immediately surrounding each dentinal tubule is called peri-tubular dentin, while the rest is inter-tubular dentin. Despite a similarity in names, this is not homologous to rod enamel and inter-rod enamel.

"cross sections of teeth" by Gorak Tek-en is licensed under CC BY 3.0 / animation and text addedAnother way to classify types of dentin is on its location relative to the pulp cavity. Mantle dentin develops first. It is a thin layer (15 to 30 μm) next to enamel (therefore, only in the crown). Mantle dentin contains few dentinal tubules, they are filled in during the maturation stage. Mantle dentin is where globular mineralization occurs. The globular dentin mineralizes and fuses together, creating a uniform appearance. Just below mantle dentin is where you find crescents of inter-globular dentin between globular dentin. Got that? If not, see Fig. 10.6. Mantle dentin is thought to be different from other dentin because it is here that odontoblasts first begin secreting proteins (near the DEJ), at which time the odontoblasts aren’t fully mature. The collagen← fibers that remain in mantle dentin run perpendicular to the DEJ. The rest of the dentin (in both the crown and roots) is circum-pulpal dentin, which mineralizes linearly, leaving dentinal tubules intact. Collagen fibers run parallel to the DEJ in circum-pulpal dentin. Mantle and circum-pulpal dentin have slightly different levels of mineralization and protein content. Mantle dentin is more elastic, which provides a cushioning effect for the enamel above (like a yoga mat).

"cross sections of teeth" by Gorak Tek-en is licensed under CC BY 3.0 / animation and text addedYet another way to classify dentin is based on when it is formed relative to the apical foramen. If this seems redundant to mantle dentin versus circum-pulpal dentin, you are mostly right. Primary dentin is the dentin formed before completion of the apical foramen, therefore it is formed prior to tooth eruption←. Secondary dentin is formed after the completion of the apical foramen (after tooth eruption). Unlike mantle versus circum-pulpal dentin, there are no major histological differences between primary and secondary dentin.

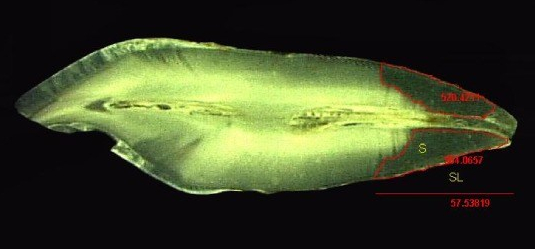

"Stereomicroscope image (5X) of tooth with measurement of Sclerotic Dentin Area (S) and Length of Sclerotic Dentin (SL)" by Selvamani M, et al, Journal of International Oral Health is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 / croppedMuch later, a tooth may suffer damage and new forms of dentin are produced to repair the injury. Odontoblasts can produce tertiary dentin and repair small amounts of damage. Tertiary dentin produced by the original odontoblasts (still in the pulp) is called reactionary dentin (or sclerotic dentin). Formation of this form of dentin involves secretion of matrix metalloproteinases from dentinal tubules. These enzymes are also used during the formation of dentin during embryogenesis. Therefore, this is another example of how wound repair recapitulates embryonic development. During embryogenesis, however, dentin is formed appositionally. Reactionary dentin mineralization occurs within dentinal tubules, causing the tubules to become occluded (to become blocked). Therefore, fewer dentinal tubules are found in reactionary dentin. Furthermore, it is the parallel dentinal tubules that give primary and secondary dentin their yellow-ish hue. With reduced or no tubules, reactionary dentin becomes more translucent (see Fig 10.11).

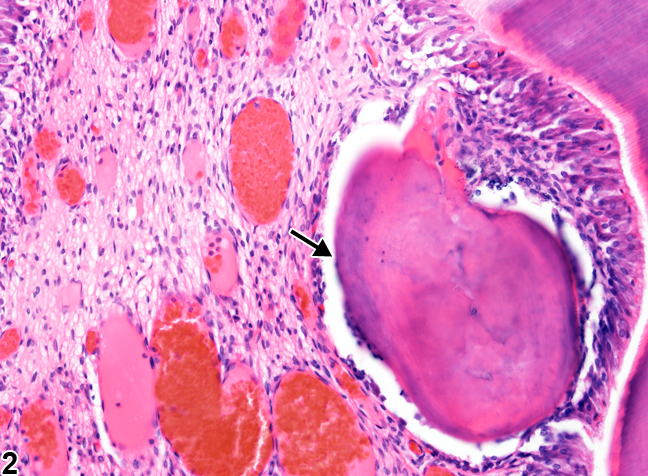

"Tooth, Pulp - Osteodentin in a male F344/N rat from a chronic study" by Cora MC, Travlos GS, at the National Toxicology Program is in the Public Domain, CC0If a large enough injury occurs as to expose the pulp chamber, destroying odontoblasts, a much more robust response is needed. First, new odontoblasts are needed, but how can we get new odontoblasts without morphogens from pre-ameloblasts? The answer is pretty cool: there is a backup system. Mesenchymal stem cells in the pulp differentiate into odontoblasts when they come into contact with a dentin-specific protein (not collagen←, but a molecule called dentin sialoprotein 2). This does not happen in a healthy tooth because odontoblast cell bodies are a barrier between dentin sialoprotein 2 and pulp mesenchymal stem cells. When those odontoblasts die (as long as there is some pulp left), new odontoblasts are induced to differentiate. The new odontoblasts form a type of tertiary dentin called reparative dentin. Reparative dentin does not form the same way dentin does during development. Dentinogenesis began at the DEJ, and layers of dentin were added appositionally, towards the pulp chamber. To form reparative dentin, odontoblasts and fibroblasts start from the pulp chamber, migrate throughout the injured area (after a hematoma forms) and secrete proteins and electrolytes. No dentinal tubules are created, these new odontoblasts secrete dentin in all directions. Some of the odontoblasts and fibroblasts become trapped within the ECM. For this reason, reparative dentin is sometimes referred to as osteodentin, because it resembles bone tissue← under the microscope more than it does tubular dentin. In fact, osteodentin may represent the phylogeny of dentin. The teeth of some species (such as eels) and the fossils of our ancient ancestors' teeth is made of osteodentin, not mantle or peri-tubular dentin.

| Type of dentin | Location | Features | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peri-tubular | Walls of tubules | Found in circum-pulpal dentin | |

| Inter-tubular | Between walls | Found in circum-pulpal dentin | |

| Mantle | Thin border next to DEJ |

No tubules Collagen perpendicular to DEJ |

|

| Circum-pulpal | Rest of tooth |

Tubules Collagen parallel to DEJ |

|

| Primary | Formed before apical foramen |

Made by original odontoblasts Contains tubules |

|

| Secondary | Formed after apical foramen | ||

| Tertiary |

Reactionary, Sclerotic |

Formed after injury |

Made by original odontoblasts Tubules filled in |

| Reparative | Formed after large injury |

Made by new odontoblasts and fibroblasts Cell trapped in calcified tissue (osteodentin) No tubules form |

|

Tomes granular layer" by Shaik Mohamed Shamsudeen is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 / letters and arrow addedRoot dentin

Roots do not contain mantle dentin, but they do contain a superficial layer of dentin that is visually distinct from the circum-pulpal dentin. Close to the border with cementum, spots are visible in a band of dentin known as Tomes’ granular layer. This layer has no known clinical significance. It is useful for orienting yourself when looking at histological sections of teeth. Those grain are not the nucleuses of cells. Older data suggested the grains are loops of dentinal tubules, but re-analysis using more advanced microscopes suggests the grains are loops of collagen← fibers. This suggests they are similar to globular dentin. Whatever the cause of the granulations is, the important concept to remember is the order of events in root formation. Odontoblasts are less mature (newer) when they are secreting dentin in Tome’s granular layer than when they are closer to the root canal, similar to globular dentin formation in the mantle region of the crown.

Clinical considerations of dentinogenesis

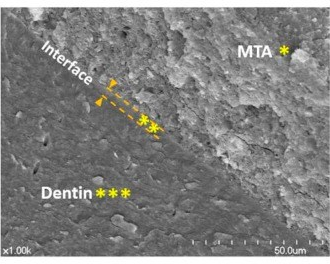

Scanning electron microscopic images that are representative of the root canal dentin and mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) interface“ by Yoo, Yeon Gee et al is licensed under CC BY 3.0Mineral aggregates

If there is a large amount of damage to dentin, the production of tertiary dentin may be too slow. When treating root resorption, or for root end filling during endodontic therapy, artificial ECM can be used. Unlike some of the artificial tissues discussed in gingival healing, solid crystals do not make good scaffolds←. The goal is to mimic something more gelatinous like pre-dentin, not crystalline dentin, whose dense matrix would inhibit migration of stem cells. Mineral aggregates provide the necessary materials required by odontoblasts without inhibiting their movement during dentinogenesis. One such compound, Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (MTA), was developed in California by Dr. Mahmoud Torabinejad. MTA contains a purified version of Portland cement plus calcium-containing minerals. The addition of mineral aggregates speeds up the formation of tertiary dentin. MTA slowly releases calcium hydroxide, which provides a raw material for mineralization of tertiary dentin, as well as attracting phosphate from the blood or ECF. Author’s note: Portland cement was invented in Portland, England. Do not apply Portland cement from your hardware store to teeth, it is caustic and may contain arsenic or other heavy metals. The Portland cement used in dentistry is highly purified.

"Dentin appearance" by Pinkmanggis is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0In one type of dental restoration (a tooth filling), a wet resin is bonded (glued) to dentin and hardened using a special light. To bond a resin to dentin, one should take into account the chemical structure of dentin. Dentin ECM contains calcium hydroxyapatite crystals, collagen← and other proteins, plus water molecules. The water molecules, along with collagen, allow dentin to bend and compress in response to stress, as opposed to harder enamel which resists stress (summarized in Table 8.3). Water molecules give dentin a moist appearance. Many bonding agents do not adhere well to a wet surface, and require dentin to be dried first. This is usually done with a volatile solvent such as ethanol. Mineral acids may be used to remove an amount of the mineral ECM of dentin, leaving behind the more porous collagen framework. This can improve bonding, somewhat similar to acid-etching of enamel. However, acid etching took advantage of the mineral differences between rod and inter-rod enamel. There is not enough of a difference between peri-tubular and inter-tubular dentin, both lose minerals when mineral acids are applied.

There is interest in the research community for developing bonding agents that adhere to wet surfaces (all living human tissues are wet). One promising area is the study of mollusk mucus. Mucus is secreted from the body, but it is similar to ground substance← in human connective tissues, especially mesenchyme←. Mucus secreted by limpets adheres to wet surfaces with great strength, and it stimulates tertiary dentin formation (link to pdf download). One of the most abundant molecules in mucus is hyaluronic acid (a major component of ground substance).

Lastly, bonding agents typically adhere to primary and secondary dentin more readily, because of the higher degree of surface area from dentinal tubules. In contrast, bonding agents do not adhere as well to tertiary dentin, where tubules are filled in or never form.

Morphogens

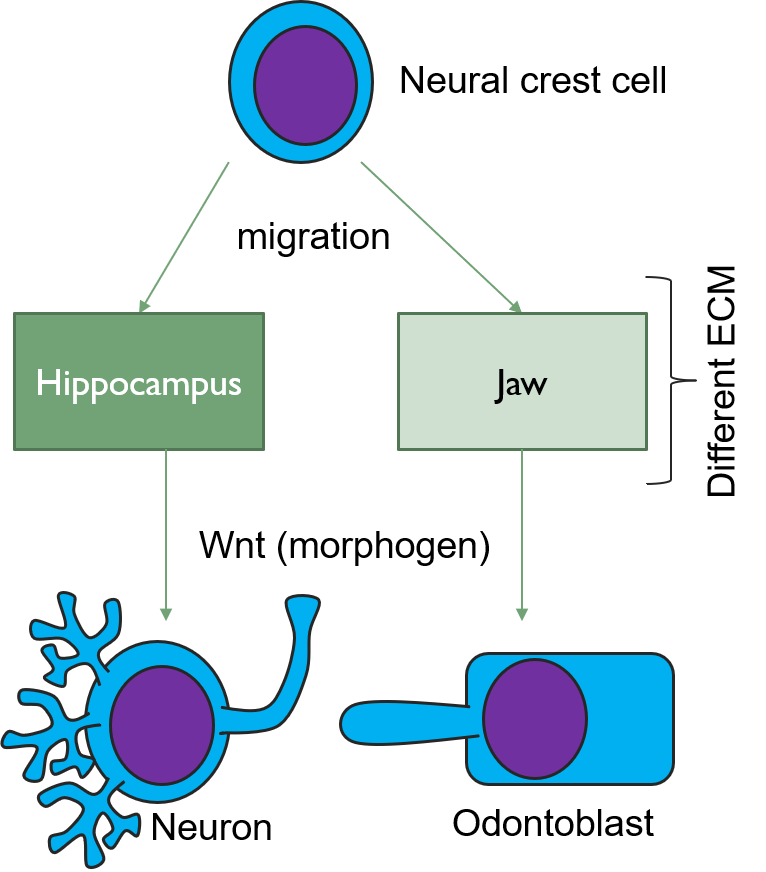

The formation of tertiary dentin requires morphogens← to induce the differentiation← of mesenchymal stem cells into new odontoblasts. As more is learned about these morphogens, it opens up the possibility to administer morphogens to speed up natural healing processes, potentially reducing the need for inorganic cements or caps. One such morphogen is a Wnt. In the brain, Wnts induce the differentiation of neural crest cells← into specific types of neurons and glia. But when neural crest cells migrate to the face and become parts of the pharyngeal arches←, the same Wnt induces them to differentiate← into odontoblasts. The difference arises because of a second morphogen. This second signal comes from the ECM, and ECM is very different in the developing brain than it is in developing neuro-mesenchyme of the pharyngeal arches. The significance of this is that a drug used to treat Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) [Tideglusib is used off-label in dentistry to boost tooth repair. We suspect it is very rare to randomly test psychoactive drugs for their use in dentistry. Prior knowledge of shared lineages, however, makes new avenues of treatment more obvious.]

Attrition and erosion

Own work” By Klaus Limpert, Scuba-limp is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0Because dentin has a lower mineral content than enamel, dentin erodes more quickly than enamel. If mantle dentin is lost, this exposes dentinal tubules in the underlying circum-pulpal dentin. Exposed tubules increases the surface area for acids to dissolve calcium hydroxyapatite crystals, speeding up dentin erosion. Surface exposure of dentinal tubules also leads to increased sensitivity of the teeth (see below).

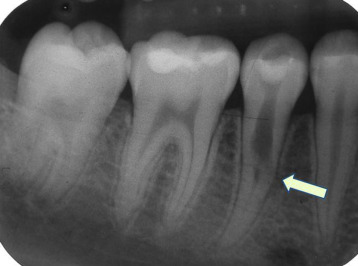

Tooth “By ADuran is licensed CC BY-SA 3.0Dentin caries

Once dental caries spread through enamel and reaches the DEJ, it spreads at an increased rate. The triangle pattern of enamel loss is quickly repeated in a new triangle of dentin caries. It is possible, but not agreed upon, that a small enough enamel caries might spread to the DEJ without causing changes visible at the surface, and upon reaching the DEJ the rate of tooth loss accelerates. Whatever the exact cause, caries can start below enamel and spread through dentin. This hidden caries is harder to detect than one at the surface of a tooth.

Dentin hypersensitivity

The loss of enamel or cementum covering dentin may expose dentinal tubules. In the crown, the few millimeters of mantle dentin at the outer surface contain few open dentinal tubules. But if enamel and mantle dentin are lost, tubules in the circum-pulpal dentin are exposed. These tubules extend to the root pulp, where nerve endings are located. Changes in the environment of the oral cavity, including the temperature, pH, alcohol level or osmotic concentration, now affect the temperature, pH, alcohol level or osmotic concentration of the pulp ECF. There is a small amount of ECF between the odontoblastic process and peritubular dentin (dentinal fluid). Changes to the chemical composition of this ECF can be detected by nerve endings, which in turn relay painful stimuli to the brain. This can be called tooth, root, cervical or cemental hypersensitivity, but it is more accurate to call it dentin hypersensitivity . Treatments for dentinal hypersensitivity include special toothpastes, mouthwashes or chewing gums that deposit minerals into exposed dentinal tubules and occlude them. Such products likely contain salts and fluoride. Alternately, varnish mineral aggregates such as Portland cement might be applied to the affected area. Conversely, with age, odontoblasts add layers of peri-tubular dentin inside dentinal tubules, causing the tubules to become narrower. As this happens, teeth become less sensitive. This may not sound so bad until you take into consideration the role that proprioception has in preventing excessive occlusal forces. Cranial nerve V is one of the larger cranial nerve, it transmits a lot of important sensory information to the brain from the teeth. With diminished sensitivity comes an increased risk of occlusal trauma.

Figure 10.20: The importance of proper dental hygiene procedures. Image credit: “Dental details” by Senior Airman Kristi Emler, US Air Force is in the Public Domain, CC0

Dentin may become exposed due to loss of cementum or enamel, or if the edge of enamel does not meet/overlap cementum. Furthermore, gingival recession exposes the thin layer of cementum to environments it is not designed to handle, making dentin exposure along the neck of the tooth the most likely area for dentinal hypersensitivity. Improper technique on the part of dental hygienists or dentists may inadvertently remove protective layers of cementum as well.

"An irregular radiolucency in the coronal third to middle third of the root" by Fang-Chi Li is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0Dentin resorption

During exfoliation of primary teeth, dentin resorption (the loss of dentin due to cell-mediated demineralization) assists in the loss of attachment between the tooth root and alveolar bone. This is mediated by odontoclasts. Odontoclasts are related to osteoclasts. Osteoclasts have baseline activity throughout life maintaining bone tissue as part of a remodeling unit←. Odontoclasts, on the other hand, are not always present, their differentiation from mesenchymal stem cells as well as their activity is regulated by different morphogens←. Dentin resorption occurring at any time other than the shedding of primary teeth is idiopathic (of unknown cause). We do understand that the dentinal tubules found throughout dentin create a large amount of surface area for odontoclasts to adhere to and trigger demineralizion. This is similar to what we observe in spongy bone: spongy bone is lost at a faster rate than compact bone because it has a higher amount of surface area (thus symptoms of osteoporosis appear first in bones with higher amounts of spongy bone, like the mandible).

Dentin resorption triggered from the pulp-cavity side is referred to as internal resorption. Conversely, external resorption occurs from the DEJ or CEJ side.

"Oral photographs from the affected individual" by unknown is licensed under CC BY 2.0Dentinogenesis Imperfecta

A mutation in the gene for one of the dentin-specific proteins (dentin sialophosphoprotein) leads to a genetic condition known as dentinogenesis imperfecta (types II and III). In this condition, the dentinal tubules are wider than normal. This in turn alters the color of dentin, causing teeth to appear more grey or bluish (similar to how reactionary dentin has a different color from healthy dentin because it lacks dentinal tubules). Unlike amelogenesis imperfecta, the teeth of people with dentinogenesis imperfecta do not have a higher susceptibility to dental caries. The teeth are weaker than normal, and are more prone to fracture and loss. The lack of one scaffold← protein leads to reduced dentin mineralization. Reduced mineralization leads to higher levels of inter-globular dentin.

Mutation to the gene for type I collagen← leads to a condition called osteogenesis imperfecta, or brittle bone disease. About 50% of people with osteogenesis imperfecta have dentinogeneis imperfecta (type I). These individuals have the dentin sialophosphoprotein, but the defect in collagen leads to brittle dentin.

"Tooth, Odontoblast necrosis" by Cesta MF, Herbert RA, Brix A, Malarkey DE, Sills RC (Eds.), National Toxicology Program Nonneoplastic Lesion Atlas is in the Public Domain, CC0Pulp overview

The dentin and pulp both develop from neuro-mesenchymal stem cells of the dental papilla. Odontoblasts make a specialized tissue, containing just one terminally differentiated cell type. The rest of the neuro-mesenchymal cells make areolar connective tissue←, which contains numerous cell types, including adult stem cells. It is here that blood vessels, nerve fibers and lymphatic vessels have space and structural support.

Histology of pulp

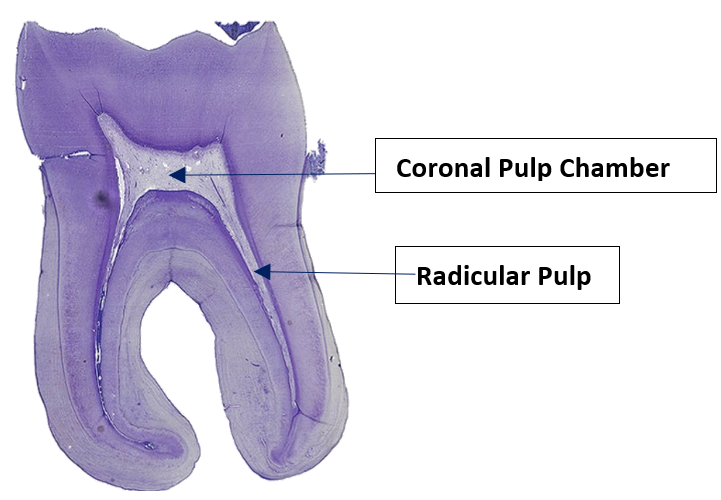

"Longituinal tooth 5" by Natdental is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0Pulp can be divided into coronal pulp and radicular pulp. The coronal pulp is in the crown of the tooth and contains smaller pulp horns beneath the cusps. Radicular pulp is in the roots, and may extend into accessory canals. Accessory canals connect the pulp to connective tissue external to the tooth, traveling laterally rather than out the apical foramen. Accessory canals form when HERS runs into a blood vessel and is forced to grow around it. Otherwise, radicular pulp terminates at the apical foramen.

Pulp Histology” by Dododopamine at the School of Dentistry, University of Dundee is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0Pulp layers

Pulp is a single tissue, but there are four layers that look different from one another under a microscope. The first is the odontoblast layer, which is closest to the dentin. Odontoblasts initially form a single layer of cells along the broad region of the DEJ. But as they add dentin, the pulp cavity becomes smaller. As the pulp cavity becomes smaller, odontoblast cell bodies crowd together, ultimately forming a thicker layer of cell bodies at the edge of the pulp cavity. Deep to the odontoblasts is what is called the cell-free zone. This zone contains cells, but they are not visible under a traditional H&E stain. Deep to that is a cell-rich zone, composed primarily of fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells, white blood cells and other connective tissue cells. Lastly is the pulp core, which contains the same types of cells, but more ground substance← spaces them apart. The pulp core is where most of the larger blood and lymphatic vessels are located.

Clinical considerations of pulp

"abcès parulique" by Damdent is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0Periapical abscess

If damage to dentin exposes pulp to oral bacteria, an infection of the pulp may occur. This usually triggers inflammation of pulp tissue, known as pulpitis. Death of pulp tissue can lead to accumulation of pus around the roots, which is called a periapical abscess. The release of inflammatory molecules from damaged tissue can lead to swelling of the overlying gingival tissue, often referred to as a gum boil. Less commonly, a gum boil may also form due to an infection of periodontal tissues, in which case it is not a periapical abscess, it is a periodontal abscess. It is possible to remove necrotic pulp surgically. If some healthy pulp remains, regeneration of the pulp may occur. This is because of the high degree of vascularization of areolar connective tissue← and the high mitotic potential of mesenchymal stem cells.

Tooth #30” By DRosenbach at English Wikipedia is in the Public Domain CC0Endodontic therapy

A periapical abscess likely requires the removal of the infected pulp tissue and replacement by a bio-compatible material that is similar in density and elasticity. This procedure is known as endodontic therapy. The preferred material used is gutta-percha, a naturally-occurring latex polymer from the sap of trees in Malaysia. It was once widely used as an insulator for electronics, but has been replaced by synthetic polymers, except in endodontic therapy. It is radiopaque because of an additive, barium sulfate. Otherwise, latex does not show on radiographs, which would make it difficult to confirm gutta percha had completely filled the pulp cavity.

Discolored maxillary left central incisor tooth" by Anandkumar Patil is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0Removal of living pulp tissue removes all cells from the tooth, including odontoblasts. This tooth is referred to as non-vital. A non-vital tooth cannot make repairs to dentin, which leads to increased brittleness and the accumulation of stains over time. Stain molecules may invade from the enamel side down dentinal tubules, or molecules from pulp necrosis may invade dentin by traveling up dentinal tubules.

If used elsewhere in the body, gutta-percha is rejected by the immune system. What is special about being inside dentin is unclear at this time, but the discovery of dentin’s protection in endodontic therapy has led to the use of dentin to protect other substances from immune rejection, such as artificial corneas in osteo-odonto keratoprosthesis (yes, pieces of tooth are inserted into an eye to restore vison).

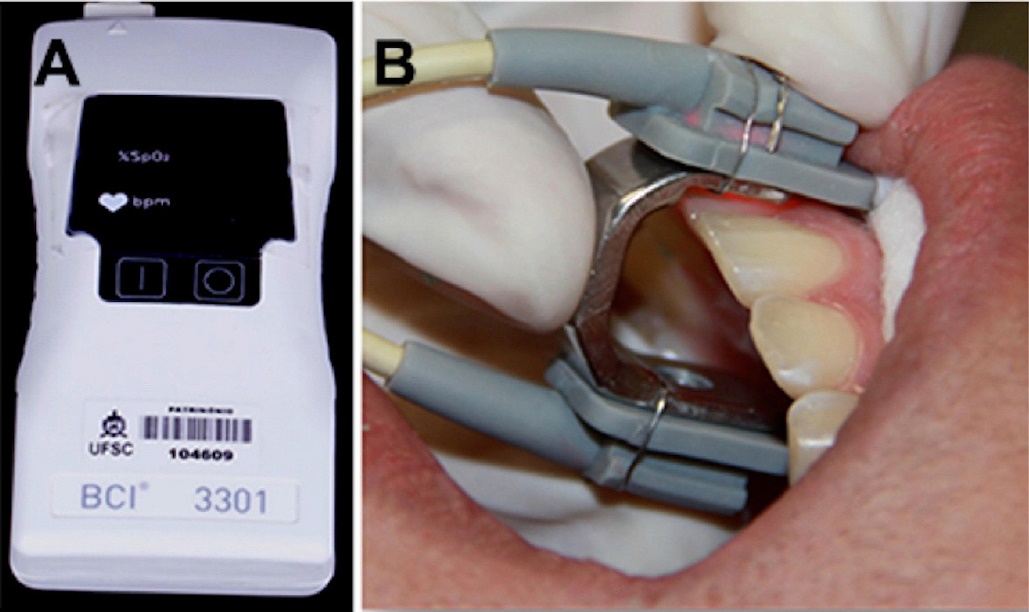

Own work” By Coronation Dental Specialty Group is licensed CC BY-SA 3.0Pulp vitality testing

Painful stimuli at the surface of the teeth are detected by nerve endings located within the pulp. Pulp vitality testing (or pulp sensitivity testing) takes advantage of this to estimate the health of the tooth pulp. An electrical stimulus is applied at the surface of teeth followed by self-reporting of the discomfort level experienced by the patient. Loss of nerve endings reduces tooth sensitivity, and indicates pulp tissue has undergone fibrosis or necrosis. However, a reduction in the diameter of dentinal tubules also reduces the ability of electrical signals at the surface to be detected within the pulp. Conversely, loss of enamel and exposure of dentinal tubules may increase sensitivity without any changes to pulp vitality.

"Pulse oximeter and sensor with specially manufactured adapter" by Lorena Ferreira Lima, et al is licensed under CC BY 4.0Because different patients report pain differently, and because factors besides the health of the pulp affect the degree of discomfort reported, false-positive and false-negative results are possible with pulp vitality testing. Other less-invasive tests exist, including pulse oximetry and laser doppler flowmetry. These measure the vascular supply to each tooth, which correlates with the vitality of the tooth. Pulse oximetry takes advantage of the color change hemoglobin undergoes as it picks up oxygen. Laser doppler flowmetry takes advantage of the doppler shift waves exhibit when they bounces off moving objects (such as flowing red blood cells) but not stationary ones– similar to the way the sound of a motorcycle changes pitch when it is rapidly travelling toward you or away from you.

Age-related changes

Because a vital tooth contains a layer of living odontoblasts, dentin becomes gradually thicker with age. This is most noticeable in the fine pulp horns, which recede with age. Couteracting this, as with many cells, the mitotic ability of mesenchymal stem cells within the pulp decreases with age. As a result, older pulp tends to contain more scar tissue (cross-linked collagen← fibers) and has decreased regenerative capability and diminished sensitivity.

Pulp stones

Elsewhere in the body, damage to connective tissue may lead to the formation of scar tissue. In the pulp, however, the presence of odontoblasts causes scar tissue to mineralize. The formation of calcified scar tissue is a rare condition known as Dystrophic calcification elsewhere in the body, but is common in pulp. Localized regions of calcification in pulp are called pulp stones (or denticles). These occur in both radicular pulp and coronal pulp. The major clincal significance of pulp stones is they may complicate endodontic therapy. Pulp stones can not only be found in pulp (free), they also appear on dentin (adherent) and within dentin (embedded).

< Chapter 9 * navigation * Chapter 11 >

Chapter review questions

The developmental history of a differentiated cell traced back to the embryonic cell from which it arises.

Mesenchyme tissue that contains neural crest cell derivatives.

A condensation of ecto-mesenchymal cells seen in histologic sections of a developing tooth.

The shape (or form) of.

Dentin and pulp are the same tissue from a function and embryology viewpoint, and are therefore referred to together as a complex.

Extra-Cellular Matrix: Materials in the body, but outside of cells. A network of macromolecules, such as fibers, enzymes, and glycoproteins, that provide structural and biochemical support to surrounding cells.

A cell of neural crest origin that is part of the outer surface of the dental pulp, and whose biological function is the formation of dentin.

The formation of dentin.

Formation and eruption of the teeth.

The stage of early tooth development where the dental organ differentiates into 4 distinct cell types 9IEE, OEE, stellate reticulum and stratum intermedium), followed by differentiation of odontoblasts and ameloblasts.

The main structural protein in the ECM of connective tissues

Extracellular matrix material involved in the repair of injured and missing tissues, allows stem cells to migrate into the injured area. It is usually replaced during regeneration.

Newly formed dentin before calcification and maturation.

The formation of enamel.

Reorganization or renovation of existing tissues, either physiological or pathological. The process can either change the characteristics of a tissue such as in blood vessel remodeling, or result in the dynamic equilibrium of a tissue such as in bone remodeling.

The embryonic process in which one group of cells directs the development of another group of cells.

The process by which animals and plants grow and change.

The ectodermal cells that lie above the dental papillae in a cap stage tooth bud.

Inner Enamel Epithelium: a layer of columnar cells located next to the dental papilla, these pre-ameloblast cells will differentiate into Ameloblasts which are responsible for secretion of enamel during tooth development.

When one cell begins to look different from another. This process involves limiting cell fate by altering gene transcription to become more specialized.

An intermediate cell type, differentiate from IEE cells, capable of inducing the differentiation of odontoblasts, which in turn induce pre-ameloblasts to differentiate into ameloblasts,.

A substance whose non-uniform distribution governs the pattern of tissue development and pattern formation.

Bone Morphogenetic Proteins are a group of signaling molecules, initially discovered for their ability to induce bone formation, now known to play crucial roles in all organ systems.

A subset of mesenchymal stem cells derived from neural crest cells rather than mesoderm, or mesoderm-derived mesenchymal stem cells induced by neural crest morphogens to adopt a more neural fate.

Without shape

An epithelium composed of one layer of square cells

Top-to-bottom polarity, where the apical side of a cell (or tissue) is different from the basolateral side

The middle of the three embryonic layers that develop during gastrulaton, mesoderm becomes most of the body's muscle and connective tissues.

rough Endoplasmic Reticulum, an organelle where membrane and secreted proteins are translated by bound ribosomes on the surface of the rER.

A membrane-bound organelle that modifies proteins from the rER and packages them up into vesicles, to be sent to lysosomes, the plasma membrane, or secreted from the cell.

Ca5(PO4)3(OH), the inorganic ECM material composed of calcium, phosphate and hydroxide ions that makes up the bulk of bone tissue.

A hard connective tissue which is mostly ECM, including collagen fibers and a calcium-phosphate crystal.

Cells present only during the embryonic period that deposit tooth enamel.

Arm-like extension of an odontoblast found within dentinal tubules.

Tiny canals that run through dentin, from the pulp cavity up to near the DEJ or CDJ

A structure inside (or outside) a cell, consisting of liquid enclosed by a lipid bilayer.

A protein that has had sugar residues attached to it in the Golgi apparatus and is often secreted.

Enzymes that degrade all kinds of extracellular matrix proteins, or process a number of bioactive molecules. They play a major role in cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, angiogenesis, and apoptosis.

Dentin-Enamel Junction

Extensions of odontoblastic processes past the DEJ into enamel, creating thin regions of hypomineralized enamel.

Similar to enamel spindles, but shorter, bushier-shaped, and do not contain odontoblastic processes.

Fingerlike projections of the epidermis, the downward-pointing counterparts to the dermal papillae.

Fingerlike projections of the apical side of the dermis, increasing the surface area between the epidermis and dermis, strengthening their connection and increasing exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and waste.

The mucous membrane lining the inside of the mouth. It is a stratified squamous epithelium, named the oral epithelium, and an underlying areolar connective tissue named the lamina propria.

Lighter-staining regions of dentin found between globular dentin spheres.

Darker-staining regions of dentin, found between mantle dentin and circumpulpal dentin.

The outer layer of dentin closest to enamel, contains few odontoblastic processes.

The largest region of dentin, containing dentinal tubules, peri-tubular dentin and inter-tubular dentin

The calcification of pre-dentin in the circumpulpal region occurs linearly, not in globs.

The overall curve that odontoblastic processes take as seen in dentin.

A small curve to dentinal tubules observed in dentin, in the opposite direction of the primary curvature.

Incremental lines in the peritubular dentin of the tooth that correspond to the daily rate of dentin formation.

Incremental growth lines seen in enamel.

Exceptionally-pronounced imbrication lines of von Ebner

A process by which epithelial cells lose polarity and cell-cell adhesion, and gain migratory and invasive properties to become mesenchymal stem cells, this normally occurs during embryonic development and wound healing.

A sequence of nucleotides in DNA that encodes the synthesis of a gene product, either RNA or protein.

The thin layer of dentin found bordering the dentinal tubule.

Thicker layer of dentin found between the thin layers of peri-tubular dentin.

A similarity due to shared lineage between a pair of structures or genes in different taxa.

The basic unit of tooth enamel, 4 μm wide, composed of a tightly packed and organized mass of hydroxyapatite crystals, hexagonal in shape.

The type of enamel found between enamel rods.

The majority of dentin, formed before completion of the apical foramen, contains both mantle dentin and circum-pulpal dentin.

A process in tooth development in which the teeth enter the mouth and become visible.

Dentin formed after completion of the apical foramen, contains only circumpulpal dentin.

dentin formed as a reaction to external stimulation, such as cavities and wear, including both reactionary and reparative dentin.

Tertiary dentin formed from a pre-existing odontoblast, contains narrow or filled-in dentinal tubules.

To state again, or to repeat.

The increase in diameter by the addition of tissue at the surface,

Multipotent cells of a connective tissue that can differentiate into a variety of cell types, including osteoblasts, fibroblasts, chondrocytes, myoblasts, blood cells and adipocytes.

Dentin produced by the differentiation of pulp stem cells becoming later odontoblast and/or osteoblast-like cells, which form a bone-like structure

The basic connective tissue cell type capable of secreting ECM components, including fibers and ground substance proteins.

Another name for reparative dentin, based on its resemblance to bone tissue, with cells trapped within dense ECM.

The history of the evolution of a species or group, especially in reference to lines of descent and relationships among broad groups of organisms.

A layer of dark granules that lie parallel to the outer surface of root dentin.

Also known as a root canal, is a treatment for infected pulp of a tooth, result in the removal and replacement of pulp and the protection of the decontaminated tooth from future microbial invasion.

Undifferentiated or partially differentiated cells that can differentiate into various cell types, and proliferate to produce more of the same stem cell.

A thin gelatinous secretion composed of primarily of glycoproteins and water.

Gel-like substances in the ECM, composed of water held in place by large molecules (proteins, glycoproteins and glycosaminoglycans).

An embryonic tissue composed of undifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells and mucous ground substance.

A very large glycosaminoglycan distributed widely throughout connective tissue ECM, epithelial, and neural tissues.

Signaling molecules first identified for their role in carcinogenesis, then for their function in embryonic development, including body axis patterning, cell fate specification, cell proliferation and cell migration.

A temporary group of cells that arise from the embryonic ectoderm, and in turn give rise to a diverse cell lineage—including melanocytes, cranio-facial cartilage and bone, teeth and periodontal tissue, smooth muscle, peripheral and enteric neurons and glia.

A series of externally visible anterior tissue bands lying under the early brain that give rise to the structures of the head and neck.

The wearing away of tooth enamel by excess acids.

Damage to a tooth that can happen when decay-causing bacteria make acids that de-mineralize tooth tissues.

A carious lesion that extends into dentin.

An occlusal dentine caries that is missed on a visual examination.

Extra-Cellular Fluid is the fluid surrounding cells, but not within blood or lymphatic vessels.

The lymph or ECF found within dentinal tubules, surrounding the odontoblastic process

Pain derived from exposed dentin in response to chemical, thermal tactile or osmotic stimuli which cannot be explained as arising from any other dental defect or disease.

The exposure in the roots of the teeth caused by a loss of gum tissue and/or retraction of the gingival margin from the crown of the teeth.

A general term for peeling or shedding, in humans it refers to the loss of dead epithelial cells or structures (hair, teeth).

The removal of dentin matrix by odontoclasts (as opposed to erosion), which occurs in the roots during tooth exfoliation.

Resorptive cell capable of demineralizing dentin by the secretion of acids and enzymes.

A cell derived from bone marrow stem cells capable of demineralizing bone tissue by the secretion of acids and enzymes, releasing calcium into the blood.

Osteoblasts and osteoclasts working together to remove old bone tissue and replace it with new bone tissue, necessary for the maintenance of healthy bones.

A disease that arises from an unknown cause.

Cemento-Enamel Junction, found in the cervical region of the tooth.

A genetic disorder that causes teeth to be discolored (most often a blue-gray or yellow-brown color) and translucent giving teeth an opalescent sheen.

A rare congenital disorder which presents with abnormal formation of enamel, unrelated to any environmental conditions.

When a cell has finished its last possible differentiation step and lost the ability to undergo mitosis.

A loose connective tissue composed of fibroblasts and other cell type, plus ground substance and all three fiber types.

A stem cell found in adult tissues (as opposed to embryonic stem cells found in embryos)

The portion of pulp in the crown of the tooth.

The portion of pulp in the roots.

A prolongation of coronal pulp extending toward the cusp of a tooth.

Smaller access ways that branch off of the main root canals.

Hertwig's Epithelial Root Sheath: A proliferation of epithelial cells located at the cervical loop of the enamel organ in a developing tooth which initiates the formation of root dentin.

The other layer of pulp containing the cell bodies of odontoblasts.

A region of pulp with fewer visible cell bodies, and a large amount of capillaries and nerve endings.

Hematoxylin and Eosin stain, typically turns proteins pink and DNA purple.

A region of the pulp containing numerous fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells and other connective tissue cells.

The center of the pulp chamber with many cells and an extensive vascular supply; except for its location, it is very similar to the cell-rich zone.

Inflammation of the pulp.

A collection of pus at the root of a tooth, usually caused by an infection that has spread from pulp to the surrounding tissues.

A small swelling formed on the gum over an abscess at the root of a tooth.

A localized collection of pus within the tissues of the periodontium.

Materials used in surgical implants, not harmful to living tissue and unlikely to be rejected by the host immune system.

No longer containing living cells.

A test which helps establish the health of the pulp of a tooth.

A molecule made by Red Blood Cells that can bind and release Oxygen molecules. It switches from a red to a maroon color as it does so, which in turn contributes to skin color.

The process of cell division, where one cell divides into two identical clones (daughter cells).

A strong but immovable connective tissue quickly made by fibroblasts, consisting primarily of highly cross-linked collagen fibers.

Discrete calcifications found in the pulp chamber of the tooth.