Building a Fact-Checking Habit

This part of the textbook is all about valuing information. I’ve emphasized several times already in this class that information often costs money—and it can be a lot of money! So by valuing information, I do mean acknowledging the time and energy that goes into information creation and how that is monetized and protected through legal structures like copyright.

Another interpretation of valuing information is recognizing the creators by giving credit to the original ideas and work of others through proper attribution and citation.

But an additional meaning of valuing information that we’ll address first is making informed choices about the information you’re using in your research and critiquing that information through careful evaluation of the creators, publications, and the systems in which the information was produced and dispersed to the audience.

We’ll talk about practical evaluation strategies, but before you can use those skills, you need to develop a habit.

The habit is simple. When you feel strong emotion—happiness, anger, pride, vindication—and that emotion pushes you to share a “fact” with others, STOP. Above all, these are the claims that you must fact-check.

Why? Because you’re already likely to check things you know are important to get right, and you’re predisposed to analyze things that put you in an intellectual frame of mind. But things that make you angry or overjoyed, well…our record as humans are not good with these things.

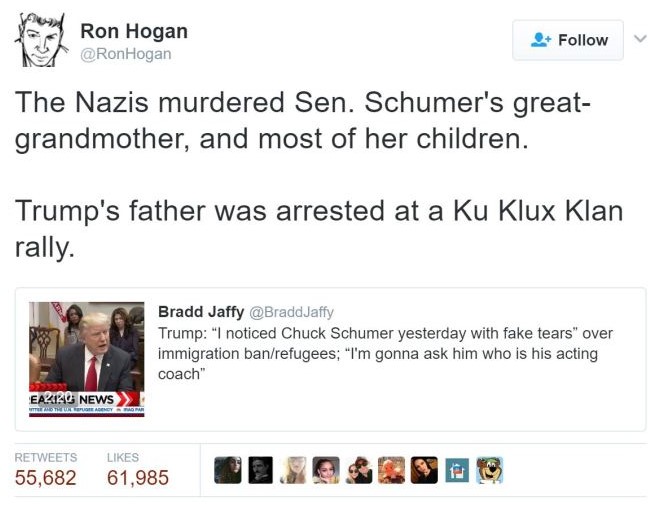

Let’s look at this Tweet as an example:

You don’t need to know much of the background of this tweet to see its emotionally charged nature. President Trump had insulted Chuck Schumer, a Democratic Senator from New York, and characterized the tears that Schumer shed during a statement about refugees as “fake tears.” This tweet reminds us that Senator Schumer’s great-grandmother died at the hands of the Nazis, which could explain Schumer’s emotional connection to the issue of refugees.

Or does it? Do we actually know that Schumer’s great-grandmother died at the hands of the Nazis? And if we are not sure this is true, should we really be retweeting it?

Our normal inclination is to ignore verification needs when we react strongly to content, and researchers have found that content that causes strong emotions (both positive and negative) spreads the fastest through our social networks. Savvy activists and advocates take advantage of this flaw of ours, getting past our filters by posting material that goes straight to our hearts.

Here’s another, non-political example (click on the image to watch):

Use your emotions as a reminder. Strong emotions should become a trigger for your new fact-checking habit. Every time content you want to share makes you feel rage, laughter, ridicule, or even a heartwarming buzz, spend 30 seconds fact-checking. It will do you well.