2.5 Criminal Justice Policies

In this section we will review policies that have had an impact on the criminal justice system. Some of these policies, like Colonialism, have been in the works for over hundreds of years, setting the stage for how justice would be implemented in America. Where others, like Disproportionate Minority Contact, have been addressed and implemented more recently as a result of identified disparities in the system.

2.5.1 Colonialism

As the word implies and history shows, colonialism was implemented in the U.S. when colonial Europeans immigrated to the Americas and took over the land. This takeover was often savage and violent, with White men entering indigenous lands, creating fear, killing some, and taking others as their property. As American history unfolded, colonial ways were implemented in the forms of government, commerce, and the implementation of justice. As a result these colonial ways led to a criminal justice system based on these colonial practices.

These colonial practices continued to shape how laws were enforced and crime was addressed, thus continuing to employ controls that affected marginalized populations. In the article, “Wicked Overseers: American Policing and Colonialism” authors noted that colonialism “should be seen not as an event but as an ongoing structure”(Steinmetz, et al., 2016, qtd Glenn, 2015). The U.S. structure has been driven by colonialism and the unfortunate impacts are still very visible in our systems today.

Two of the many impacts of colonialism, found within the criminal justice system, have been the focus on 1) police being used to enforce laws created by the majority and 2) punishment being implemented as a resolve for justice. As we will discuss in future chapters on policing and corrections, these colonial strategies have created a hierarchical system and criminal justice policies that have had drastic impacts on minority groups within the states. Steinmetz, et al noted that these colonial police policies “have taken the form of slave patrols, the enforcement of segregative laws such as the black codes and Jim Crow laws, and…the war on drugs, broken-windows and zero-tolerance policing, and police militarization” (2016).

As a result, some are looking at the idea of “Decolonization” as a way to respond to these colonial systems and thus “fix” what has been established. Cortez noted in “Decolonization and Justice,” that decolonization ‘involves undoing colonial ideologies contained in “intellectual, psychological, and physical forms and it won’t happen by magic, happenstance, or friendly agreement’” (2022, qtd Asadullah, 2021, p. 3). Thus continuing to identify policies that have been implemented which are negatively impacting marginalized populations and re-evaluating these policies.

2.5.2 Disproportionate Minority Contact

As we will discuss in this text, there are significant racial and ethnic disparities within the criminal justice system. Disproportionate Minority Contact (DMC) resulted in juvenile justice policy through the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP, 2014). DMC “refers to rates of contact with the juvenile justice system among juveniles of a specific minority group that are significantly different from rates of contact for white non-Hispanic juveniles” (OJJDP, 2014.) Data show that BIPOC youth are over represented at every stage of the juvenile justice system, from arrest to adjudication. In 1974, the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA) was signed into law. As a result, OJJDP was implemented, requiring States to annually report their DMC rates of contact, however, these initial DMC rates were for confinement not contact. It became evident through years of research that disproportionate minority confinement was only one part of the problem. The real problem was the contact at every stage and not just at the end. This prompted a change in the terminology to reflect the need to address the overrepresentation of BIPOC in the justice system as a whole.

In 2018, the Juvenile Justice Reform Act of 2018 (JJRA) amended the JJDPA, requiring states to not only report on contacts but to also “implement policy, practice, and system improvement strategies…to identify and reduce racial and ethnic disparities (R/ED) among youth who come into contact with the juvenile justice system” (OJJDP, 2019). This topic will be covered more fully in the juvenile justice chapter later in the text but is one example of the implementation of policy within the criminal justice system.

2.5.3 Racial and Political Divide

Another impact of Criminal Justice policy has to do with the politically motivated and divided parties running the American government. The two major political parties (Democrats and Republicans) have an evolving history in relation to supporting, or not, racial issues and inequities.

Watch the History Two-Party Democratic Republican System Explained United States Democrats Republicans Origin to learn more about the evolution of the political parties in the United States.

With the evolution of the different political parties came differing focuses and policies. This created a flip-flop rotation every 4-8 years, in which one individual within a party would be elected and would focus their time in office fighting for equitable changes and policies, and then when their rotation ended, the opposing party leader would be elected, turning their party’s interests and views in the opposing direction. As a result of the historical progression of the parties and their policy focuses, the United States has become extremely divided in both its policies and views.

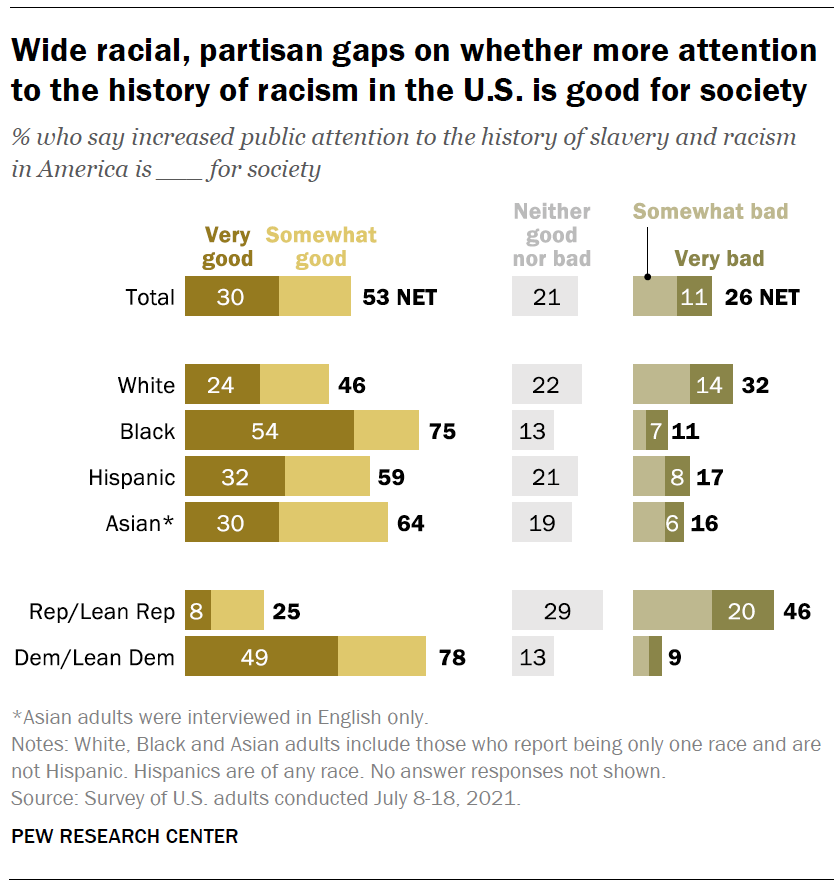

One example of this can be found in a Pew Research Center report, “Deep Divisions in Americans’ Views of Nation’s Racial History — and How To Address It.” They noted in the report that they conducted a “study to understand how the American public views the country’s progress toward ensuring equal rights for all Americans, regardless of their racial or ethnic background” (Nadeem, 2021). In figure 2.4. from the Pew Research Center, the divisions by parties and racial and ethnic groups are broken down on this issue.

Figure 2.4. Bar graphs by race/ethnicity in response to whether more attention to the history of racism in the U.S. is “good” (on a scale) for society. Pew Research Center’s Americans’ Views on Nation’s Racial History (Graph).

In the American Journal of Criminal article, “The Politics of Racial Disparity Reform: Racial Inequality and Criminal Justice Policymaking in the States,” the author notes how “prior literature” has suggested that “elected officials promulgate punitive, racially disparate criminal justice policies due to partisanship and racial fears” (Donnelly, 2017). The article goes on to discuss policy reform and how some elected officials are pursuing change through policy reform.

The state of California is one example of how policy reform, spurred by a federal court order, has motivated additional policy change. In 2011, a federal court order was issued “to address severe prison overcrowding” but Californians took it a few steps further. They addressed policies for “realignment” which routed individuals who would have previously been prison-bound to shorter-term jail sentences or community alternatives. They passed Proposition 47, reclassifying “a number of drug and property felonies to misdemeanor” crimes (Lofstrom, et al, 2021).

The CATO Institute’s article titled, “Racial Disparities in Criminal Justice Outcomes Lessons from California’s Recent Reforms,” cited some impressive statistical improvements noting,

“Racial disparities narrowed much more for the offenses targeted by the reform. The gap between African Americans and whites in arrest rates for property and drug offenses dropped by about 24 percent, and the bookings gap shrank by almost 33 percent. Even more striking, gaps between African Americans and whites in arrest and booking rates for drug felonies decreased by about 36 percent and 55 percent, respectively.” (Lofstrom, et al, 2021)

With changing times and new political leaders on a constant rotation, it is up for debate as to whether policies will continue to change across America as a whole or remain isolated reaching communities on a smaller level. Re-evaluation has been one way of moving in that direction.

2.5.4 Licenses and Attributions for Criminal Justice Policies

Figure 2.4. Americans’ Views on Nation’s Racial History © The Pew Trust. Used under fair use.