10.4 Delinquency

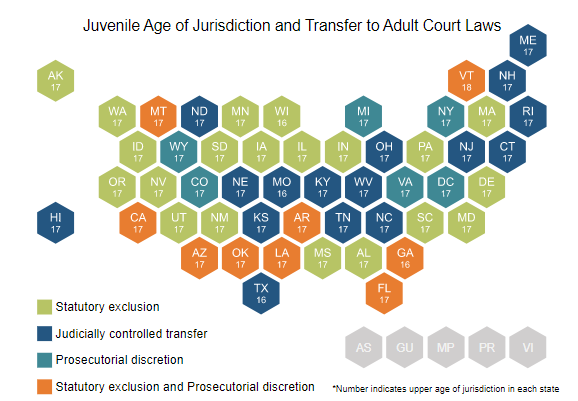

Before the creation of the juvenile court, there was no such thing as “delinquency.” Youth were convicted of crimes, the same as adults. Just as the concept of “childhood” is socially constructed, scholars also say that “juvenile delinquency” is likewise socially constructed as a result of social, economic, and religious changes (Feld, 1999). The juvenile court oversees cases for youth between the ages of seven and 17. Seven is considered the lower limit of the reaches or protections of the juvenile justice system, while 17 is the upper limit. At 18, youth are considered adults and are tried under the laws of the adult criminal justice system. However, some states have differing upper age limits. For example, in Oregon, the Oregon Youth Authority houses youth until the age of 25. Other states have similar provisions, and although the lower limit is seven years of age, most states do not intervene in cases under nine. In figure 10.2., you can see the juvenile age breakdown across the United States.

Figure 10.2. A map of States in the United States noting Juvenile Age of Jurisdiction and Transfer to Adult Court Laws.

10.4.1 Youth Processing Ages

After the creation of the juvenile court, the child savers and reformers were worried that restricting the court to only deal with criminal youth would make the court function like an adult criminal court rather than a rehabilitative parental figure. Within a couple of years of its founding, amendments to the Illinois Juvenile Court Act broadened the definition of delinquency to include incorrigible youth, or otherwise unruly and out of the control of their parents (Feld, 1999). The definition of juvenile delinquency now included status offenses or offenses that are only illegal because of the age of the offender. Examples include: drinking alcohol, running away, ungovernability, truancy (skipping school), and curfew violations. Overall, the juvenile justice system is responsible for youth who are considered dependent, neglected, incorrigible, delinquent, and/or status offenders.

To learn more check out the Podcast: Caught. WNYC studios presents a nine part series about justice-involved youth. Check out the the series at Caught: Episodes | WNYC Studios | Podcasts.

The purpose of the original court was to act in a rehabilitative ideal. The main function was to emphasize reform and treatment over punishment and punitive action (Feld, 1999). Terminology in the court is even different, to denote the separate nature from the adversarial adult processes. To initiate the juvenile court process, a petition is filed “in the welfare of the child,” whereas this is called an indictment in the adult criminal process. The proceedings of juvenile courts are referred to as “hearings,” instead of trials, as in adult courts. Juvenile courts find youths to be “delinquent,” rather than criminal or guilty of an offense, and juvenile delinquents are given a “disposition,” instead of a sentence, as in adult criminal courts, meaning dispositions are the punishment imposed by the courts on the youth.

10.4.2 School to Prison Pipeline

Most theorists and researchers agree that there is a correlation between poor school performance and delinquency. Negative experiences in school foster delinquent behavior, but there is more to delinquency than failing social studies class or algebra. The school to prison pipeline (SPP) refers to the increasing connection between school failure, school disciplinary policies, and student involvement in the justice system. In their book, Kim, Losen and Hewitt (2010; p. 1) define the SPP as “the intersection of a K–12 educational system and a juvenile justice system” through education and discipline structures that facilitate school disengagement (Rocque & Snelligs, 2018). These systems are marred with low graduation rates, high dropout rates, high number of suspensions and expulsions, and zero tolerance disciplinary practices. These practices disproportionately place students of color into the criminal justice system.

When school officials unfairly apply harsh disciplinary measures or overuse referrals to law enforcement agencies through the use of school resource officers (SROs) or zero-tolerance policies, they ignore the underlying causes of the behavior and set up vulnerable students for failure. Students from marginalized groups are at the greatest risk of being drawn into the school to prison pipeline. Black students in particular miss an average of five times as many instructional days because of out-of-school suspensions compared with White students. And missing school increases the likelihood of dropping out of school which then increases the likelihood of other negative life outcomes such as poverty or lower earning potential over one’s life, poor health, substance abuse, and contact with the criminal justice system. In fact, students who are suspended are over five times more likely to be charged with a violent crime as an adult (Wright et al., 2014).

African Americans, American and Alaskan Natives, low-income students, those with mental disabilities, and those at risk of academic failure are disproportionately involved with the SPP (Welch et al., 2022). There continues to be a very clear racial disparity between White and Black students in school discipline, including office referrals, suspensions, and expulsions. Structural or institutional racism refers to systems or policies that create or maintain racial inequalities. It is not a stretch to correlate SPP and discriminatory discipline actions with institutional racism within the schools.

What can we do? As we’ll talk about later in the chapter, restorative justice practices have the potential to eliminate the school to prison pipeline. Restorative justice (RJ) seeks to heal harm, understand the causes of behavior, and build a sense of community. RJ can help create a supportive school environment, but school officials also need to actively work on addressing cultural biases and understanding educational trauma to ensure that schools provide an equal chance for educational success for all students.

10.4.2.1 In the News: The Prison Pipeline

6-year-old Zachery Christy, a first grader in Newark Delaware, was suspended for 45 days for bringing a spork to school. The camping utensil, which contains a spoon, fork, knife, and bottle opener was a gift from Cubs Scouts. The first grader brought the camping utensil to school although the “dangerous weapon” violated zero tolerance rules at the school.

Spurred in part by the Columbine and Virginia Tech shootings, many school districts around the country adopted zero-tolerance policies on the possession of weapons on school grounds. More recently, there has been growing debate over whether the policies have gone too far. (Urbina, 2009)

Zero Tolerance policies are strict adherence to regulations and bans to prevent undesirable behaviors. The idea behind them is to promote student safety and to be fair and consistent with all children. The idea behind them is to promote a one size fits all approach, so as to treat all children equally, however, research suggests that minority youth are unfairly targeted by such practices, which counters their purposes. Zero Tolerance policies contribute to the school to prison pipeline. Children who interact with law enforcement at earlier ages are more likely to end up in the criminal justice system.

What was thought to remove discretion from school administrators in issues of discipline, actually results in African American students being more likely to be suspended or expelled than other students for the same offenses? Additionally, the suspension or expulsion from school severs ties and harms the relationship youth have with school, making it harder for the youth to return and engage.

For Zachary and his spork, it’s more than breaking his attachment to school and his teachers. He fears being teased by the other students. If his parents choose not to home-school him, he must spend the next 45 days in the district’s reform school.

Watch Rethinking zero tolerance: Dean Allen Groves at TEDxUVA to learn more.

10.4.3 Disproportionate Minority Contact (DMC)

In an article published by the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange, titled, “Why Disproportionate Minority Contact Exists, What to Do,” author Rebecca Fix explained that Disproportionate minority contact (DMC) “occurs when the proportion of youth of color who pass through the juvenile justice system exceeds the proportion of youth of color in the general population.” (2018). It can be assessed at every stage of the juvenile justice system, from arrest to adjudication. Considerable research on disproportionate minority contact has been conducted over the past three decades. Research shows minority youth are over-represented in arrests, sentencing, waiver, and secure placement. African American, Latinx/Hispanic American, and Indigenous/Native American youth are disproportionately represented at every single stage of the justice system. States receiving federal grant money are required to address DMC “regardless of whether those disparities were motivated by intentional discrimination or justified by ‘legitimate’ agency interests” (Johnson, 2007). However, it still exists. For example, African American males represent roughly 35 percent of juvenile arrest rates but only 8 percent of the U.S. juvenile population. This is problematic (Fix, 2018).

When racial/ethnic minority youth are disproportionately involved in the juvenile justice system, they have a higher chance of suffering the consequences that stem from being justice-involved, such as mental and physical health issues, lower academic achievement, poorer employment potential, and are more than 13 times more likely to be arrested and incarcerated again.

Some argue that DMC is a direct and measurable result of institutional racism. This can be seen in instances of “differential selection” when professionals in the juvenile justice system, such as police officers, judges, and probation officers, treat ethnic and minority youth more harshly than White youth. Similarly, “justice by geography” suggests that youth are treated and perhaps even stereotyped based on the areas where they are located during their interactions with juvenile justice professionals.

Another factor associated with DMC is “differential opportunities” or privileges for treatment and prevention are available for some youth and not for others. For example, “European American youth are more likely” to have access to treatment programs and benefit from restorative justice in their schools and communities (Fix, 2018).

10.4.4 Licenses and Attributions for Delinquency

“Delinquency” by Alison Burke and Megan Gonzalez is adapted from “10.4 Delinquency” by Alison S. Burke in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity; added DEI content.

Figure 10.2. Juvenile Age of Jurisdiction and Transfer to Adult Court Laws under fair use.