9.2 The Role of Community Corrections

Community corrections is a system imposed by the court on individuals who have committed a crime in which they serve all or part of their sentence/sanction through community-based placements and programs as an alternative to incarceration. Like incarcerated corrections, community corrections have similar goals: to promote public safety, to administer punishment, and to rehabilitate individuals, but unlike incarcerated corrections, this is done in a very different way.

In this chapter, we will consider how these different community corrections options reach each of these goals. We will highlight various different programs available through the Community Corrections parts of the justice system. Along with highlighting and defining these options, we will discuss what the current research, government, and community groups are reporting about program effectiveness.

9.2.1 Diversion

The bulk of this chapter deals with official actions from the courts on individuals in the community while they are under some sanction. However, a large number of individuals do not even make it that far in the system due to some form of diversion. Diversion is a process whereby an individual, at some stage, is routed away from continuing on in the formal justice process. Diversion is an action that would effectively keep a person in the community and, in some cases, out of the criminal justice system altogether.

9.2.1.1 Different Diversion points in the System

Diversion can come as early as the initial contact with a law enforcement officer. The discretion an officer uses could be considered a diversion, as the officer decides whether the individual needs to continue on the justice path. It could be a verbal warning, a warning ticket, or just a decision by the officer not to issue a formal ticket (citation).

Officers may also recognize the person has a need that is not being fulfilled and thus identify an underlying reason the person may be committing a crime. For example, a person is trespassing on someone else’s property to find a place to sleep. The officer has the legal authority to issue a citation for trespass if the property owner allows and thus arrests the person, but the underlying issue may be the person’s housing need. Could the officer divert the person to a shelter or other housing option, instead of issuing the citation and arresting them? One such diversion program in Marion County, Oregon is Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD). The program partners law enforcement officers with community resources and mentors. It trains officers to identify these underlying needs, thus finding support for those they are coming into contact with in the community and not just automatically routing them through the justice system without any support for the underlying issue.

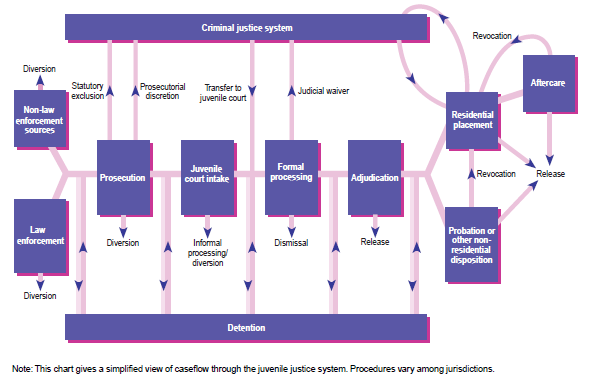

Diversion can also be more formal, for instance, a diversion can be issued by a judge in lieu of a judgment, or as a condition of a judgment. In a formal diversion process, for example, a judge could offer a person the chance to complete a diversion program in place of a sentence, making it a condition of the judgment. For example, if the person committed a crime due to a substance abuse problem, the judge could offer the person substance abuse treatment and then effectively nullify the judgment once the person has successfully completed the diversion. In figure 9.1, you will find a graph outlining how diversion could be applied at various points in the justice system.

Figure 9.1. Justice System Flow Chart with various diversion options noted along the path.

It is difficult to know the exact amount of diversions that occur in the United States, especially across the variety of places where diversion can occur. It is also difficult to determine if there are inequities in how diversions are applied across populations. These diversion options could save the courts or corrections systems hundreds of millions of dollars and keep individuals in the community instead of incarcerating them. The Prison Policy Initiative highlights in their article, Building exits off the highway of mass-incarceration: Diversion programs explained, many of the ways diversion can be implemented to address incarceration issues nationally.

9.2.2 Intermediate Sanctions

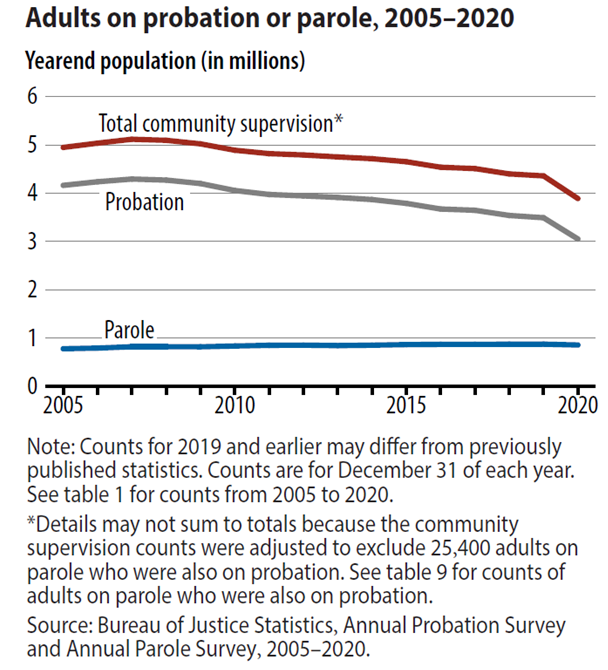

Community corrections have changed dramatically over the last half-century. Due to a rapid and overwhelming increase in the incarcerated population, largely based on policy changes, we have witnessed an immense increase in the use of sanctions at the community level; this includes probation. Probation is a form of a suspended sentence, in that the jail or prison sentence of the convicted individual is suspended, for the privilege of serving conditions of supervision in the community. We will discuss probation in further detail in the coming sections. One thing to note is it has only been within the most recent 15 years that we have seen a decrease in community corrections (figure 9.2.).

Figure 9.2. Decrease from 2005–2020 of those on parole, probation, and community supervision.

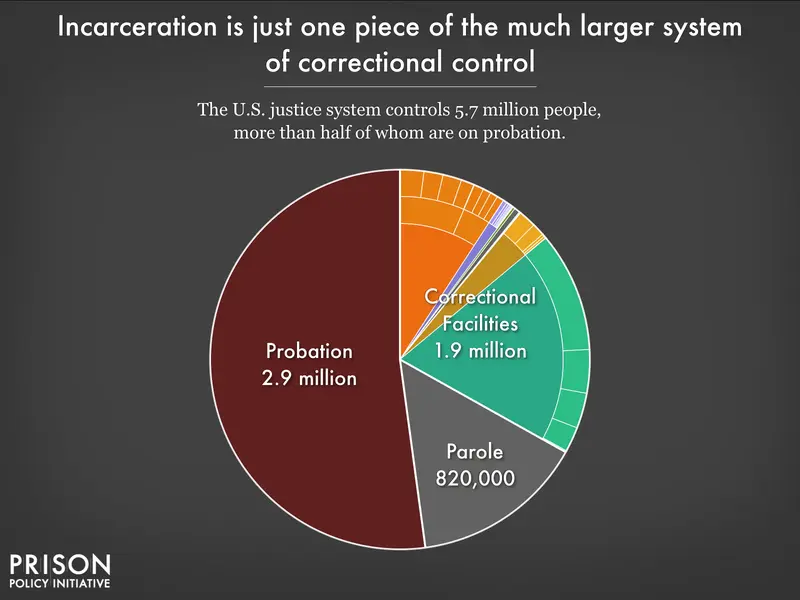

As noted in the Bureau of Justice’s article, the number of individuals on probation hovers around 3 million, with another million in some form of community-level control, for a total of about 4 million under community supervision, probation, or parole (Kaeble, 2021). Because of the sheer volume of these intermediate sanctions, it is important to put this in perspective of jails and prisons. In figure 9.3., you can see this breakdown more clearly.

Figure 9.3. Breakdown of correctional control populations, specifically probation making up more than 50 percent of the overall total.

This graphic does not include the volume of people in the community corrections outside of regular probation or parole (which is about another million) (Kaeble, 2021). Still, it sheds light on just how much probation is used. It is important to understand that most individuals under correctional control are not in prisons and jails in the United States. The majority of people within correctional control fall under sanctions like probation, intensive supervision probation, post-prison supervision, parole, boot camps, drug courts, and transitional housing, among others. This section will discuss the history and effectiveness of some forms of intermediate sanctions used in the United States, as well as the inequities that affect some populations as a result.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was a fundamental shift in corrections. This is largely due to the “Nothing Works” dogma in rehabilitation. Many reforms were made toward the housing of individuals. Some liked this idea because they did not trust the government’s attempts at rehabilitation. Others were pleased as there was more of an emphasis placed on control. Rooted in deterrence theory and to a lesser extent incapacitation, intermediate sanctions promised greater control over the growing incarcerated population at reduced cost. Because of these promises such programs were quickly welcomed across the nation. However, upon review, we can see that these approaches failed to fully fulfill these promises.

9.2.3 Probation

Probation is arguably the oldest, and certainly the largest, of the intermediate sanctions. Its roots stem from concepts of common law from England, like many of our other legal/correctional practices. In early American courts, a person could be released on their own recognizance if they promised to be responsible and pay back what they owed. In the early 1840s, John Agustus, a Boston bootmaker, regularly attended court and began to supervise these individuals as a Surety. A Surety was a person who would help these individuals in court, making sure they repaid these costs to the courts. We would consider John Augustus as the Father of Probation, for his work in the courts in Boston in the 1840s and 1850s. Augustus, pictured below, would take in many of these individuals, providing options like work and housing, to help ensure these individuals would remain crime-free and pay back society. He continued this practice for nearly two decades, effectively becoming the first probation officer. For a more lengthy historical discussion of probation, see The History of Probation | County of San Mateo, CA. An image of John Agustus can be seen in figure 9.4.

Figure 9.4. Image of John Augustus.

Probation is a form of a suspended sentence, in that the jail or prison sentence of the convicted individual is suspended, for the privilege of serving conditions of supervision in the community. Conditions of probation often include: reporting to a probation officer, submitting to random drug screenings, not associating with known felons, paying court costs, restitution, and damages, attending treatment/programming, and other conditions. Probation lengths vary greatly, as do the conditions of probation placed on an individual. Almost all individuals on probation will have at least one condition of their probation. Some have many conditions, depending on the seriousness of the conviction. In contrast, others have just a blanket condition that is imposed on all in that jurisdiction or for that conviction type. To review a list of state-mandated conditions of probation for Oregon, see ORS 137.540—Conditions of probation.

Juvenile probation departments were established within all states by the 1920s, and by the middle of the 1950s all states had adult probation.

Probation officers usually work directly for the state or federal government but can be assigned to local or municipal agencies. Many counties have a community justice level structure where probation offices operate. Within these offices, probation officers are assigned cases (caseload) to manage. The volume of cases in a probation officer’s caseload can vary from just a few clients, if they are high need/risk clients, to several hundred individuals. It depends on the jurisdiction, the local office’s structure, and the probation officers’ abilities.

The role of the probation officer (PO) is complex and sometimes diametrically opposing. A PO’s primary function is to enforce compliance of individuals on probation. This is done through check-ins, random drug screenings, and enforcement of other conditions that are placed on the individuals. Additionally, the PO may go out into the field to serve warrants, do home checks for compliance, and even make arrests if need be.

However, at the same time, a probation officer is trying to help individuals on probation succeed. This is done by trying to help individuals get jobs or schooling, enter into substance or alcohol programs, and offering general support. This is why the job of the PO is complex, as they are trying to be supportive but also have to enforce compliance. Many equate this to being a parent. Recently, there has been a movement within probation to have probation officers act more like coaches and mentors rather than just disciplinarians. Here is a talk about how POs can view themselves as coaches to enact positive change within individuals on probation.

Another primary function of a probation officer is to complete pre-sentence investigation reports on individuals going through the court process. A pre-sentence investigation report or PSI is a psycho-social workup on a person headed to trial. It includes basic background information on an individual, such as age, education, relationships, physical and mental health, employment, military service, social history, and substance abuse history. It also has a detailed account of the current offense, witness or victim impact statements of the event, and prior offenses (criminal records), which are tracked across numerous agencies. The PSI also has a section that is devoted to a plan of supervision or recommendations, which are created by the PO. These usually list the conditions of probation recommendations if probation is to be granted.

An article published by the Office of Justice Programs noted that judges use this information during sentencing discussions and hearings and will usually follow these recommendations (Norman Ed.D. & Wadman, 2000). Thus, many of the conditions of probation are prescribed by the PO. There has been criticism in allowing POs to complete the PSIs as the defense counsel has little to no input in the content of the report or the recommendations. Due to this, some entities hire professionals outside of the criminal justice system (social workers, psychiatrists, etc.) to compile the investigative reports.

9.2.3.1 Individuals on Probation

As stated, several million people are on probation, serving various lengths of probation, and under numerous types of conditions. Additionally, the convictions which place individuals on probation vary, to include misdemeanors and felonies. Individuals serve their probation at the state level or federal level.

Probation is a privilege, but it most certainly comes with conditions. Due to how cheap probation is, relative to jail or prison, and the ability for lower-risk individuals to maintain connections within their community, millions of people will be on probation in the United States at any given time.

Other important factors that help to decide if a person warrants probation are found within the PSI and other risk and need assessments (RNA). RNAs are instruments used to determine the level of risk and need a person has to recidivate or commit new crimes. If the person is prosocial, has an education, a job, and a family, these are all considered as ties to the community, making them lower risk than those who don’t have these ties. These ties to the community could weaken or break if a person was incarcerated. Providing an alternative to incarceration and instead imposing a sanction while allowing the person to stay in the community is often the approach utilized within probation and other intermediate sanctions. To learn more about RNAs check out the National Institute of Justice’s article on Redesigning Risk and Needs Assessment in Corrections.

9.2.3.2 Probation Effectiveness

There are mixed reviews about probation. Recently, the Bureau of Justice Statistics listed the successful completion rate at about 43 percent in 2020 (Kaeble, 2021). In 2008–2013, this number has been reported higher, upwards of 65 percent (Huberman & Bonczar, 2014). There are a host of reasons listed for unsuccessful completion, which include: incarcerated on a new sentence/charge, or placement for the current sentence/charge, absconding (fleeing jurisdiction), discharged to warrant or detainer, other unsatisfactory reason, death, or some other unknown or not reported reason.

Unsuccessful completion can often include a concept called tourniquet sentencing. Tourniquet sentencing occurs when the restriction levels of a sanction are increased, due to non-compliance, in order to force compliance. There have been disparities in how the revocations and sanctions are imposed as outlined in this study titled, Examining Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Probation Revocation | Urban Institute.

9.2.3.3 Intensive Supervised Probation

Intensive Supervision Probation (ISP) began in the late 1950s and early 1960s in California. The basic premise was to allow caseworkers (POs) to have smaller caseloads and increase the level of treatment across individuals. Many promised multiple success measures. If an individual was revoked because of a technical violation due to an increase in control, they were not seen as a failure. They were seen as a success because of the way the public was served by the recidivism. However, this went directly against the notion that ISPs could save money. Over time, the earlier forms of ISPs become less popular.

In the 1980s, a newer model of the ISP was created in Georgia. More emphasis was placed on the control aspect rather than on treatment. Further, less emphasis was placed on the reduction of money saved.

ISP and regular probation are similar, except for the frequency of contacts with POs, the increases in surveillance and monitoring, and usually the volume of conditions. Rather than meeting a PO once a month in regular probation, a person on ISP would likely be meeting with their PO weekly or even more frequently. Additionally, individuals on ISP normally submit drug screens weekly. The increased conditions of supervision more frequently include more substance abuse treatment, either in the form of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Narcotics Anonymous (NA), or some other residential or outpatient substance abuse treatment programs. Thus, the core difference concerns increased surveillance and control over the individual on ISP.

9.2.3.4 IPS Effectiveness

While initial praise of the newer model for its increased control was evidenced by its rapid spread through the States, some researchers questioned its effectiveness. One of the largest studies of ISPs was conducted in conjunction with the RAND Corporation. They examined the effectiveness of ISPs in reducing recidivism and saving costs. In a random sample of 14 cities across nine states, they evaluated the reductions of recidivism against a sample of individuals on regular probation. Their findings suggested that there were higher amounts of technical violations, which were probably substance violations, but there were no significant differences between control-centered ISPs and regular probation as far as new arrests. Moreover, when looking at outcomes over three years, they found that recidivism rates were slightly higher for these ISPs (39 percent) vs. regular probation (33 percent) (Petersilia & Deschenes, 2004). Also, there were no substantive cost savings.

Other studies have produced similar findings regarding the effects of non-treatment oriented ISPs. While these findings might be better than prison recidivism rates, there were no reductions in prison overcrowding defined as the number of individuals incarcerated exceeding the available prison bed space, meaning there was no impact on the number of individuals incarcerated and thus still insufficient resources, which was one of the goals of implementing ISP.

9.2.4 Boot Camps/Shock Incarceration

Another form of intermediate sanction may be seen in the creation of boot camps, also known as shock incarceration facilities. Developed in the 1980s in Georgia, boot camps were targeted to youths and adults and seen as a way to alter individuals through a “shock” effect. Essentially, boot camps are programs designed to change the recidivism rate through a physical change. Designed around a militaristic ideal, boot camps operated on the assumption that a regimen of strict physical exercise would teach structure and discipline in youths. Once again, because of a high level of face validity (this looks like it will work, so it must work), boot camps flourished in the 1980s and 1990s. To learn more about Boot Camps check out this YouTube video (figure 9.5).

Figure 9.5. “Jail without Walls – How does that work?! | Free Doc Bites | Free Documentary [Youtube Video].”

9.2.4.1 Boot Camps/Shock Incarceration Effectiveness

While there are some positive results; generally, boot camps fail to produce the desired reductions in recidivism as noted in a research study published by the National Institute of Justice (Parent, 2018). For prosocial individuals, structure and discipline can be advantageous. However, when individuals of differing levels of antisocial attitudes, antisocial associates, antisocial temperament (personality), and antisocial (criminal history) are all mixed together, reductions in recidivism generally do not appear.

As discussed in the rehabilitation section, criminogenic needs are often not addressed within boot camps. They fail to reduce recidivism for several reasons. First, since boot camps fail to address criminogenic needs, they tend not to be effective. Second, because of the lower admission requirements of boot camps, individuals are generally “lumped” together into a start date within a boot camp. Therefore, high-risk individuals and low-risk individuals are placed together, building a cohesive group. Thus, lower-risk individuals gain antisocial associates that are high-risk. Finally, when boot camps emphasize the increase of physicality rather than behavioral change, it generally does not reduce aggressive behavior (antisocial personality & recidivism). A recent meta-analysis (a study of studies of a topic) published by the Campbell Systematic Reviews found this to be the case (Wilson et al., 2003). For more information on the status of boot camps, please see Practice Profile: Adult Boot Camps | CrimeSolutions, National Institute of Justice.

9.2.5 Specialty Courts

Specialty Courts are courts designed to handle individuals charged or convicted with specific crimes or who have specific needs related to their crimes. The idea is that these courts are better equipped to address the specific issues the individual faces. They are unique because the courtroom works in a non-adversarial way to identify supportive programs to successfully rehabilitate the individual. Judges, prosecutors, case workers, program coordinators, and others all work together within the specialty court to develop individual treatment and programming plans. In many cases, successful completion of these plans allows for the individual’s charges to be dismissed or expunged. For a listing of some of the nationally-recognized specialty courts visit the National Drug Court Resource Center.

Drug Courts are one of the specialty types of courts first developed in the mid-1980s in Dade County, Florida. As with other intermediate sanctions, drug courts flourished in the United States rapidly, to the point that they are now in every state. Currently, more than 3,800 drug, treatment, or specialty courts operate in the United States, as reported by the Office of Justice Programs (2022). With the growing popularity of drug courts, jurisdictions began incorporating other specialty courts, including Veterans Courts, Mental Health Courts, Domestic Violence Courts, Family Courts, Reentry Courts, and others. To learn more about Drug Courts, watch the YouTube video in figure 9.6.

Figure 9.6. ”Part 1: What are Drug Courts? [Youtube Video].”

9.2.5.1 Specialty Court Effectiveness

While the results on Specialty Courts are mixed, as a whole, drug courts are more favorable than the control of boot camps and ISPs. The results are mixed, largely due to how successes and failures are assessed and tracked. If only talking about the cost savings versus jail or prison, they are seen as an effective community alternative. If looking at recidivism, it depends if the metric is looking at relapses, solely drug charges, any arrests, or persistence models (length of time before arrest). As a whole, the risk of being rearrested for a drug crime for individuals from drug courts has shown lower rates than their comparison group. While other research, shared by the Vera Institute, has demonstrated that graduates of drug court programs were half as likely to recidivate (10 percent vs. 20 percent) (Fluellen & Trone, 2000). To learn more about the effectiveness of Drug Courts watch the video in figure 9.7. While more research is still required, specialty courts are currently seen as an effective community alternative.

Figure 9.7. “Part 3: Drug Courts are Effective [Youtube Video].”

9.2.6 House Arrest/Electronic Monitoring

House arrest is where an individual is remanded to stay home for confinement as a punishment, in lieu of jail or prison. There are built-in provisions where individuals are permitted to attend places of worship, places of employment, and food places. Otherwise, individuals are expected to be home. It is difficult to assess how many are on house arrest at any given time, as these are often short stents given during early stages of probation or pretrial release.

A component that is often paired with the house arrest model is electronic monitoring (EM). This electronic bracelet or device is equipped with Global Position Systems (GPS). The individual wears the device and an agency official tracks their actions and locations to ensure they only travel and move within the confines of their conditions. To learn more about the growth in EM use, review the article Use of Electronic Offender-Tracking Devices Expands Sharply | Pew Charitable Trust.

9.2.6.1 House Arrest/Electronic Monitoring Effectiveness

As mentioned above, house arrest is often joined with EM. Many of the studies incorporate both sanctions at the same time. Given the difficulty in separating EM from house arrest in studies, less is known about the independent effects of house arrest. However, it is certainly a cost-saving mechanism over other forms of sanctions. There is a relatively no-cost to low-cost for house arrest, not coupled with electronic monitoring, especially when comparing house arrest to intensive supervised probation. In all, house arrest would probably best serve individuals with low criminogenic risks and needs. However, it is also argued that those individuals need little sanctions already to be successful. Thus, the utility of house arrest is debatable.

The cost of pairing house arrest with EM can be similar to that of a cell phone contract payment each month, and these costs often fall on the individual and not the agency to cover. This can cause financial hardship on the individual, and outside of tracking the person’s location to ensure they are where they are supposed to be, the agencies have to impose additional rules. Due to the rise of the use of EM during the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been quite a few critics of EM, as noted in George Washington University Law School’s research titled, the Electronic Prisons: The Operation of Ankle Monitoring in the Criminal Legal System.

9.2.7 Community Residential Facilities

Community Residential Facilities (CRFs) have long been used to control/house individuals. Dating back to the early 1800s from England and Ireland, halfway houses began around 1820 in Massachusetts. Initially, they were designed to help a person “get back on their feet” and were generally funded benevolently by non-profit organizations like the Salvation Army.

Currently, halfway houses are typically used as a stopping point for individuals coming out of prisons to assist with reentry into the community. Still, they have also recently been used as more secure measures of monitoring individuals in place of going to prison. They are even used as a test measure of parole. With the creation of the International Halfway House Association (IHHA) in 1964, halfway houses have become an integral part of every state, with mixed but more promising results than ISPs or boot camps. The core design of a halfway house is meant to be a place where individuals can get back on their feet halfway out of prison. However, as stated, their uses have evolved, becoming residential or even partial residential places where individuals under correctional control can check in, and find reprieve or assistance in order to rejoin society as normal functioning members.

There are some issues regarding the examination of halfway houses. The IHHA breaks down halfway houses into four groups along two dimensions. As discussed, halfway houses were initially funded by private non-profit organizations. However, many halfway houses today (in part due to the IHHA) are both privately and federally (and State) funded. Additionally, halfway houses are also divided into supportive and interventive groups. That is, halfway houses that serve only a minimal function (a place to stay while reintegrating back into society) are generally labeled supportive, where interventive halfway houses typically have multiple treatment modalities and may have up to 500 beds. However, most halfway houses fall somewhere in the middle of these two continuums.

Other forms of Community Residential Facilities (CRFs) are often called Community Correctional Centers (CCCs), Transition Centers (TCs), or Community-Based Correctional Facilities (CBCFs), among other names. From this point, these variations will all be considered as CRFs, as there are many varieties of facility types and names. However, even two community residential facilities with the same name can be different, as the functions of CRFs can be multifaceted. CRFs can function similarly to a halfway house, they can provide a stop for individuals just checking in for the day before they go off to their jobs, they can be used for outpatient services, even residential services where there is a need for public control/safety.

The overall benefit of CRFs is their ability to have an increased focus on rehabilitation at a lower cost than a State institution. This is where their greatest effect can materialize if there is adherence to the principles of effective intervention. As we touched on in the first section on punishment, the principles of effective intervention have been demonstrated to have the best impacts on reductions in recidivism. Collectively, these are called the Principles of Effective Intervention or PEI. These include proper identification of criminogenic risks and needs of individuals, using evidence-based practices that address these items, matching and sorting clients appropriately, and responsivity in terms of programs and services.

The National Institute of Corrections defines evidence-based practices as “the objective, balanced and responsible use of current research and the best available data to guide policy and practice decisions, such that outcomes from consumers are improved” (2022). Based on this definition, Corrections agencies employ evidence-based practices to use the best techniques possible to help individuals who have committed crimes make positive changes. For a detailed account of how the PEI integrates into community corrections, see this detailed report by the National Institute of Corrections under the U.S. Department of Justice: Implementing Evidence-Based Practice in Community Corrections: The Principles of Effective Intervention.

9.2.7.1 CFR Effectiveness

Because of the variations in halfway houses, researchers find them difficult to assess. For instance, it may be difficult to generalize because of the variability. Second, gathering a representative comparison may also prove difficult. That is, halfway houses may have increased recidivism, reduced recidivism, or had no effect. Although clouded, one could argue that halfway houses are at least useful in the sense that these individuals who received more treatment fared no worse than individuals who needed less treatment.

As a whole, halfway house studies show mixed results. That is, some studies yield reductions in recidivism, while some show no difference, and others show almost equal increases. When disaggregated by type, programs using the principles of effective interventions generally have better reductions in recidivism. One difficulty with understanding the effectiveness of halfway houses may be within their funding. As stated, there are numerous revenue streams for creating and managing a halfway house, including for-profit agencies. This design may override the design of providing the level of care comprehensive enough to match the level of need of the individuals in the halfway houses. As with the other intermediate sanctions, it is important to note that using the principles of effective intervention are among the driving causes of their success.

What should come as no surprise, as is the theme with correctional practices in the community, CRFs have mixed results. This is largely dependent on the composition of the facility, the individuals within the facility, and the programs offered. When individuals are lumped together in non-directive programs that do not adhere to the PEI, the outcomes of CRFs are not favorable over jail, prison, or probation. However, when CRFs separate individuals based on risk, putting more programming with the higher-risk clients and little programming on the low-level clients, the outcomes are substantially better. For example, in a study on CRFs, Lowenkamp and Latessa found that when the individuals were separated by their risk, targeting higher-risk individuals, much larger reductions in recidivism can be achieved (Lowenkamp & Latessa, 2004).

Unfortunately, many CRFs do not adhere to these principles, and thus, their effectiveness is not as positive. As stated, this is the case for many of these agencies within community corrections. When programs do not follow the principles of effective intervention, they do not fare as well. For a recent report on the status of Community-Based Correctional Facilities, see a question and answer session with the PEW Foundation and Dr. Joan Petersillia titled, What Works in Community Corrections.

9.2.8 Restorative Justice

The process of restorative justice (RJ) programs is often linked with community justice organizations and is normally carried out within the community. Therefore, RJ is discussed here in the community corrections section. Restorative justice is a community-based and trauma-informed practice used to build relationships, strengthen communities, encourage accountability, repair harm, and restore relationships when wrongdoings occur. As an intervention following wrongdoing, restorative justice works for the people who have caused harm, the victim(s), and the community members impacted.

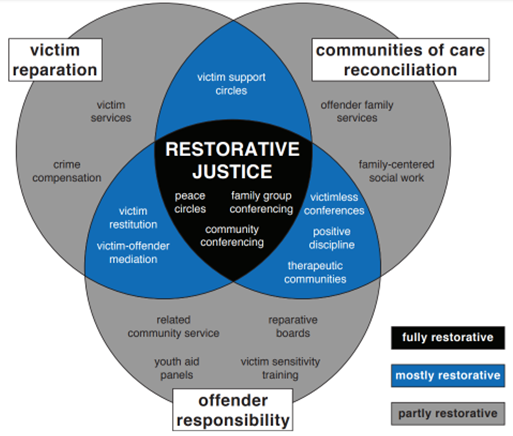

Working with a restorative justice facilitator, participants identify harms, needs, and obligations, then make a plan to repair the harm and put things as right as possible. This process, restorative justice conferencing, can also be called victim-offender dialogues. It is within this process that multiple items can occur. First, the victim can be heard within the scope of both the community and the scope of the offense discussed. This provides the victim(s) an opportunity to express the impact on them but also to understand what was happening from the perspective of the transgressor. At the same time, it allows the person committing the action to potentially take responsibility for the acts committed directly to the victim(s) and the community as a whole. This restorative process provides a level of healing that is often unique. In figure 9.8, you can see the different processes that can occur during the different types of dialogues within restorative justice conferences. To learn more about the restorative process, review the Defining Restorative article.

Figure 9.8. Venn Diagram of Restorative Justice showing the unions and intersections of victim reparation, communities of care reconciliation, and offender responsibility.

9.2.8.1 Restorative Justice Effectiveness

For over a quarter century, restorative justice has been demonstrated to show positive outcomes in accountability of harm and satisfaction in the restorative justice process for both offenders and victims. This is true for adults, as well as juveniles, who go through the restorative justice process. Recently, there have been questions about whether a cognitive change occurs in the thought process of the individuals completing a restorative justice program. A growing body of research demonstrates the change in cognitive changes that may occur through the successful completion of restorative justice conferencing. This will be an area of increasing interest for practitioners as restorative justice continues to be included in the toolkit of actions within the justice system. For additional thoughts on restorative justice from a judge’s perspective, check out the following TedTalk titled, Wesley Saint Clair: The case for restorative justice in juvenile courts | TED Talk.

9.2.9 Parole and Post Prison Supervision

Parole is an individual’s release (under conditions) after serving a portion of their sentence. It is also accompanied by the threat of re-incarceration if warranted. As with most concepts in our legal system, their roots of parole can be traced back to concepts from England and Europe. If John Agustus is known as the founding father of probation, then Alexander Maconochie and Zebulon Brockway could be identified as two of the founding fathers of parole based on their published work related to early parole-like systems (figure 9.9 and 9.10).

Figure 9.9. Image of Alexander Maconchie.

Figure 9.10. Image of Zebulon Brockway.

Both men were prison reformists during a time in history when many thought incarceration was the solution to crime. They wrote about and implemented, on a small scale, penal systems which rewarded well-behaved incarcerated individuals with the ability to earn “marks” or points toward shortening their sentences and thus allowed early release with stipulations for rejoining the community.

Parole today has greatly evolved based on American values and concepts. Parole in the United States began as a concept at the first American Prison Association meeting in 1870. At the time, there was much support for corrections reform in America. Advocates for reform helped to create the concept of parole and how it would look in the United States, and plans to develop parole grew from there. Parole authorities began establishing within the states, and by the mid-1940s, all states had a parole authority. Parole boards and state parole authorities have fluctuated over the years, but the concept is still practiced to varying degrees today. It is different from probation, which often operates under the judicial branch. Parole typically operates under the executive branch and is aligned with the departments of corrections, as parole is a direct extension of prison terms and release.

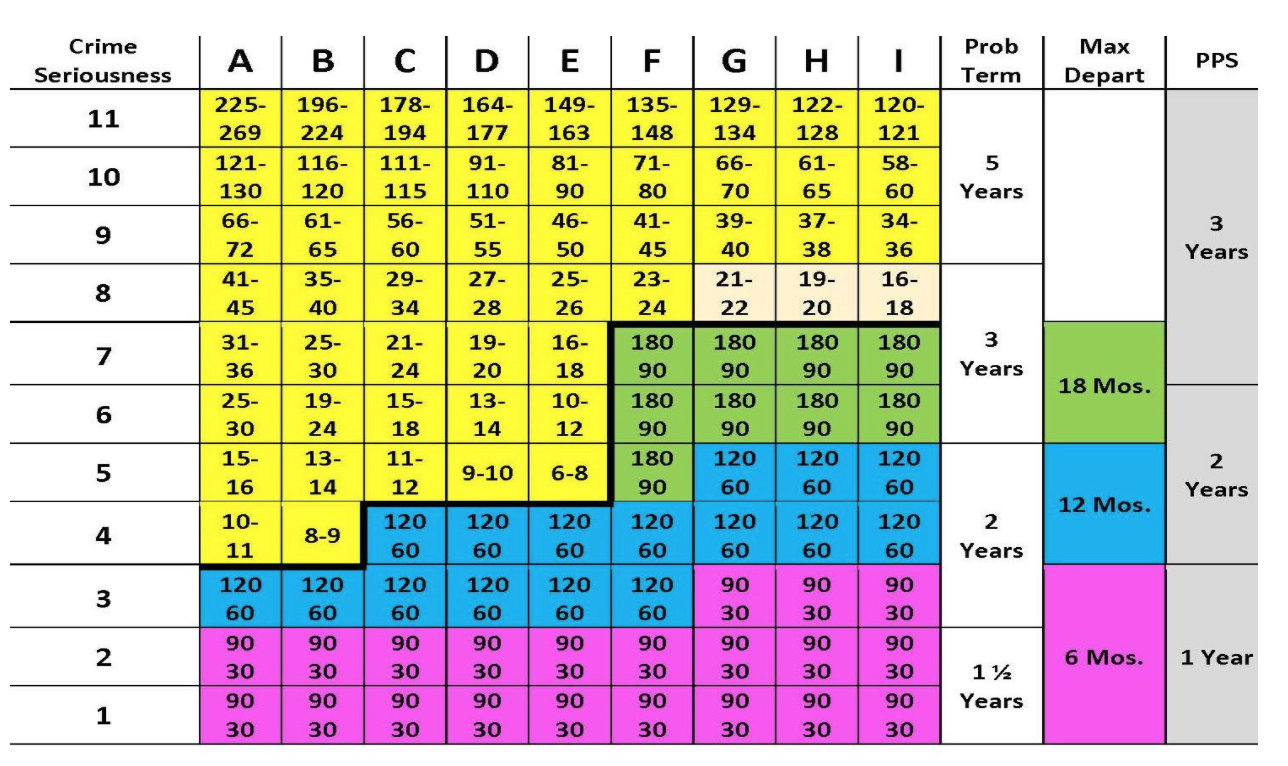

Many states operate a post-prison supervision (PPS) addendum to their sentencing matrix for the punishment of individuals, which is similar to parole in that the individual’s release (under conditions) occurs after serving their prison sentence. As you can see in figure 9.11, the PPS section in gray represents the recommended times for parole (post-prison supervision).

Figure 9.11. Oregon Sentencing Guideline Grid outlining the various amounts of incarceration, probation and pps.

Today, there are three basic types of parole in the United States, discretionary, mandatory, and expiatory. Discretionary parole is when an individual is eligible for parole or goes before a parole board prior to their mandatory parole eligibility date. It is at the discretion of the parole board to grant parole (with conditions) for these individuals. These individuals are generally well-behaving people who have demonstrated they can function within society (have completed all required programming). Discretionary parole had seen a rapid increase in the 1980s but took a marked decrease starting in the early 1990s. In more recent years, it is continuing to return as a viable release mechanism for over 100,000 individuals a year, as noted in a Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report (Hughes et al., 2001).

Mandatory parole occurs when an individual hits a particular point in time in their sentence. When a person is sent to prison, two clocks begin. The first clock is forward counting and continues until the individuals’ last day. The second clock starts at the end of their sentence and starts to work backward, proportional to the “good days” an individual has. Good days are days that a person is free from incidents, write-ups, tickets, or other ways to describe rule infractions. For instance, for every week that an individual maintains good behavior, they might get two days taken off of the end of their sentence. When these two times converge, this would be the point at which mandatory parole could kick in for them. This must also be conditioned by truth in sentencing legislation, or what is considered an 85 percent rule.

Many states have laws in place that stipulate that an individual is not eligible for mandatory parole until they hit 85 percent of their original sentence. Even though the date for the good days would be before 85 percent of a sentence is served, they would only be eligible for mandatory parole once they had achieved 85 percent of their sentence. Recently, states have begun to soften these 85 percent rules as another valve to reduce crowding issues. The Hughes et al. (2001) article also provides their proportions, indicating a direct inverse relationship to discretionary parole during the 1990s. As discretionary parole went down, mandatory parole went up. This is logical though, as once they had passed a date for discretionary parole, the next date would be their mandatory parole date. These proportions of releases switched in the 1990s (figure 9.12).

Figure 9.12. Three types of parole releases from state Prison from 1980–2000.

Perhaps most troubling is the Expiatory Release. We see a slow increase of expiatory release in the chart, which continued to climb in the 2000s. Expiatory release (a similar idea to post-prison supervision) means that a person has served their entire sentence length and is being released to the community, not because of their warranted behavior change but based on the end of their sentence and the need to accommodate incoming individuals. This sometimes means the person has misbehaved enough to nullify their “good days.” This is unfortunate, because of the three types of release, it could be argued that these are the individuals who need the most post-prison supervision and yet, these are the individuals who are typically receiving the smallest amounts of community supervision because the majority of their sentence was completed while incarcerated. With the newer idea of post-prison supervision, individuals are serving their entire sentence behind bars and then have a set amount of time on post-prison supervision in the community following the incarcerated sentence.

9.2.9.1 Parole Effectiveness

Successful parole completion rates hover around 50 percent, given a particular year. In the Hughes et al. (2001) article just mentioned, successful completion was roughly 42 percent in 1999. The same issues for failure that are found in probation completion are found in parole completion, including: revocation failures, new charges, absconding, and other infractions. This lower-than-expected success rate has prompted many critics to argue against parole. It is suggested that we are being too lenient on some while keeping lower-level individuals in prison for too long. It is also argued that we are releasing dangerous individuals into the community.

Whatever the criticisms are, the questions around parole still remain. What are we to do with the hundreds of thousands of individuals let out of prison each year? A more modern term for parole is called re-entry. The next section covers current issues within corrections, including what we do for individuals who are re-entering society.

9.2.10 Licenses and Attributions for The Role of Community Corrections

“The Role of Community Corrections” by Megan Gonzalez is adapted from “9.1 Diversion”, “9.2 Intermediate Sanctions”, “9.3 Probation”, “9.4 Boot Campus/Shock Incarceration”, “9.5 Drug Courts”, “9.6 Halfway Houses”, “9.8 House Arrest”, “9.9 Community Residential Facilities”, “9.10 Restorative Justice”, and “9.11 Parole” by David Carter in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity; added DEI content.

Figure 9.1. Case Flow Diagram by The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention/U.S. Department of Justice is in the Public Domain.

Figure 9.2. Adults on Probation or Parole, 2005–2020 by the Bureau of Justice Statistics/U.S. Department of Justice/Danielle Kaeble is in the Public Domain.

Figure 9.3. Incarceration is just one piece of the much larger system of correctional control © Prison Policy Initiative. All Rights Reserved, Used with permission materials.

Figure 9.4. John Augustus (Figure) is in the Public Domain.

Figure 9.5. “Jail without Walls-How does that work?!” © Free Documentary. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 9.6. “Part 1:What are Drug Courts?” © AmericanUnivJPO. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 9.7. “Part 3:Drug Courts are Effective” © AmericanUnivJPO. License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 9.8. Defining Restorative © International Institute for Restorative Practices. Used under fair use.

Figure 9.9. Alexander Maconchie (Figure) is in the Public Domain.

Figure 9.10. Zebulon Brockway (Figure) is in the Public Domain.

Figure 9.11. Oregon Sentencing Guidelines Grid © The State of Oregon Criminal Justice Commission. Used under fair use.

Figure 9.12. Percentage of Release from State Prison by method of release 1980-2000 by Trudi Radkee, information from the Bureau of Justice Statistics/U.S. Department of Justice/Timothy Hughes/Doris James is in the Public Domain.