1.6 Interactionist View

Typically, in our society, a deviant act becomes a criminal act that can be prohibited and punished under criminal law when a crime is deemed socially harmful or dangerous to society (Goode, 2016). In criminology, we often cover a wide array of harms that can include economic, physical, emotional, social, and environmental. The critical thing to note is that we do not want to create laws against everything in society, so we must draw a line between what we consider deviant and unusual versus dangerous and criminal. For example, some people do not support tattoos and argue they are deviant, but it would be challenging to suggest they are dangerous to individuals and society. However, thirty years ago, it may have been acceptable to put into dress code rules guiding our physical conduct in the workspace that people may not have visible tattoos and may not be as vocal as they would be today. Today, tattoos may be seen as more normalized and acceptable. This could lead to many upset employees saying those are unfair rules in their work of employment if they are against the dress code.

We have a basis for understanding the differences between deviance, rule violations, and criminal law violations. Therefore we can now discuss who determines if a law becomes criminalized or decriminalized in the United States. A criminalized act is when a deviant act becomes criminal, and law is written, with defined sanctions, that can be enforced by the criminal justice system (Farmer, 2016).

1.6.1 Jaywalking (Example)

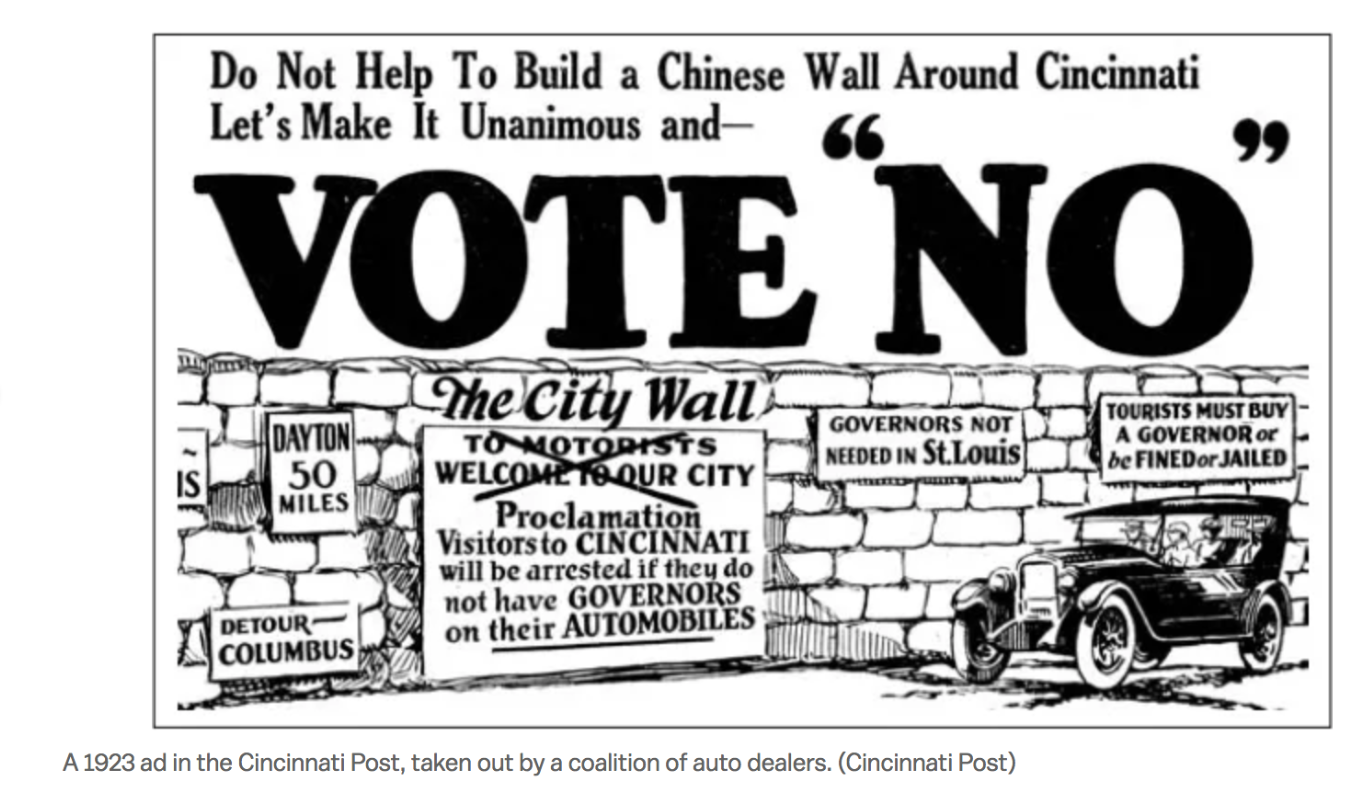

In the 1920s, auto groups aggressively fought to redefine who owned the city street. As cars began to spread to the streets of America, the number of pedestrians killed by cars skyrocketed. At this time, the public was outraged that elderly and children were dying in what was viewed as ‘pleasure cars’ because, at this time, our society was structured very differently and did not rely on vehicles. Judges often ruled that the car was to blame in most pedestrian deaths and drivers were charged with manslaughter, regardless of the circumstances. In 1923, 42,000 Cincinnati residents signed a petition for a ballot initiative that would require all cars to have a governor limiting them to 25 miles per hour, which upset auto dealers and spurred them into action to send letters out to vote against the measure.

Figure 1.1. Vote No.

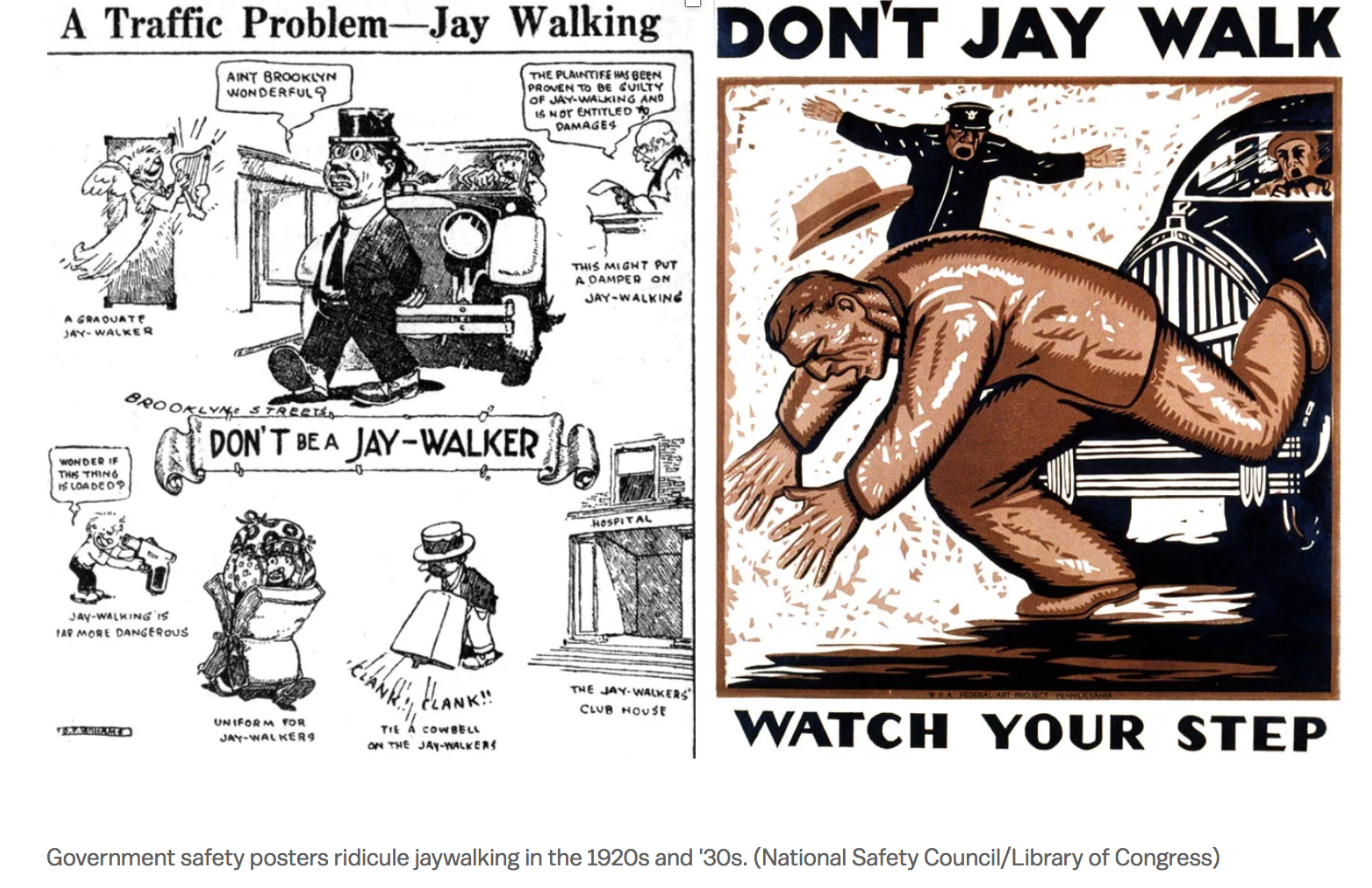

It was at this point that automakers, dealers, and others worked to redefine the street so that pedestrians, not cars, would be restricted. Today, these law changes can be seen in our expectations for pedestrians to only cross at crosswalks.

Figure 1.2. Don’t Jaywalk.

Watch this video to understand the derogatory origins of jaywalking which explains how the auto industry created a criminal act through propaganda.

1.6.2 Licenses and Attributions for Interactionist View

Figure 1.1. Vote No a 1923 ad in the Cincinnati Post is in the Public Domain.

Figure 1.2. Don’t Jaywalk a government poster from 1928 is in the Public Domain.

“1.5. Interactionist View” by Sam Arungwa is adapted from “1.4. Interactionist View” by Shanell Sanchez in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity.